| Herbert E. Stokes, Jr. 422nd/Headquarters |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

A

CITIZEN-SOLDIER’S TALE:

My World

War II Experiences

By Herbert

E. Stokes

When World War II ended in Europe in 1945, I

was a member of the 106th Infantry Division, stationed near Nantes,

France, helping contain some German troops that were bypassed during the

invasion and were still occupying the French seaports of St. Nazaire and

Lorient.

I still have

fond memories of going into Nantes the night Germany surrendered and

participating in the celebration.

In 1995,

fifty

years later, I thought there might be a

celebration in Nantes, commemorating the end of the war in Europe, if

so, I wanted to be in on it. I wrote the 106th Division Veterans

Association to see whether anything was planned and who might be

interested in going. They didn’t know, but they included my letter in

their quarterly publication, the Lion’s Cub, suggesting that anyone who

might know give me a call.

I didn’t get any calls, but it didn’t matter because there wasn’t a

celebration of

V-E Day

in Nantes that year.

Even though I didn’t receive any phone calls

about the celebration, I did get an e-mail from Wesley Johnston, whose

father had fought in Europe as a member of the 7th Armored Division.

Wesley’s father had died while Wesley was still too young to learn about

his dad’s experiences in the war, and he wanted to learn more about

them. He did know that the 7th Armored Division had supported the 106th

Infantry Division during the "Battle

of the Bulge" in December 1944, and thought I might have some

information he could include in a book that he was writing about his

father’s war experiences and especially in that particular battle. I had

never written about my own experiences during the war, but since I was

involved in that battle, I sent him an e-mail telling him what I about

remembered about it. I told someone in my family about the e-mail, and

several members said that they would like to hear more about my

experiences. I hadn’t talked much about them before, so I agreed to

write something. Now, some 65 years later, I'm finally getting around to

doing so.

Much of the reason for it taking so long is

that I know that I didn’t do anything heroic or particularly interesting

and I’m sure that my experiences were not any more exciting than those

of millions of others.

Part of my

reason for doing it now is that my Parkinson’s disease seems to be

getting worse (including my memory) and I know I probably won’t be able

to finish what I started writing about if I wait much longer. Since I’ve

discovered that I can use a dictation program with my computer to make

the job easier, I’ve run out of excuses for not doing what I promised to

do years ago.

I’ve tried to

make the account as reader friendly as I know how.

Most readers will have access to a computer, so I have used “hyperlinks”

to make it easy for them to get definitions and other information about

events and topics of particular interest. Clicking on any words or

phrases in the blue type that indicate

the presence of a

hyperlink, will take them directly to a source on the Internet.

Or, if they should want to learn more about something that doesn’t have

a hyperlink, all they need to do is use the Google search box on their

browser. I have included photos of places and people that I mention in

the narrative in the references section at the end of the paper.

I plan to make this account of my

experiences available at no cost to anyone who anyone who would like to

have it. All I need is a request and information about how to get it to

them. It will available as CDs formatted to play on Windows or Macintosh

computers, as an attachment to an e-mail or as a printed copy by

“snail-mail”. I am in the process of building a web site, where the

description can be accessed and read on desktop or laptop computers,

iPads, iPhones and Blackberries. My phone numbers are (325) 695-3442 and

660-6857, and my e-mail addresses are (in order of preference)

herbstokes@aol.com, herbstokes2@me.com, or

herbstokes@sbcglobal.net.

Eager

Beaver I’ll never forget how excited I was when I heard the Japanese had bombed Pearl Harbor and declared war on the United States. It was Sunday afternoon, December 7, 1941 and I was at work as doorman at the Queen Theater in Abilene, Texas. I was a senior in high school, had just turned seventeen a month earlier and like most boys my age, I was eager to get involved. I was still seventeen when I graduated from high school the next spring, and had received a scholarship Hardin-Simmons University to play in the H-SU Cowboy Band. I decided to go ahead and enroll in the summer session. When I heard that seventeen-year olds were eligible for the Navy’s V-12 College Training Program and that if I could get accepted, it could lead to getting a commission

Induction

and Basic Training

At Ft.

Sill, we were tested extensively to determine assignments. I was happy

when I heard that I had scored high enough on the tests to be accepted

in the ASTP. Soon, I boarded a train and was on my way to the Infantry

School in the Harmony Church area at

Ft. Benning, Georgia.

I spent the next three months

there, going through basic infantry training. The training included

learning about the army, how to take orders, how to do “close-order

drills”, a lot of callisthenic exercises and other physical conditioning

stuff, such as running obstacle courses and going on “forced marches”.

The marches were designed to build endurance while wearing a 45-pound

back pack carrying an 8-pound rifle. It also involved a lot of “dog

work” such as KP duty

and spending hours cleaning “cosmoline” grease off old

Enfield rifles

that were left over from

World War I. We

also learned how to find our way at night through a Georgia swamp

without being bitten by water moccasins, armed only with a flashlight

and a compass, and how to crawl on our bellies under barbed wire without

getting our rumps or hit by a machine gun aimed about six inches over

our head. The training was

tough, but it was good preparation for the events to come.

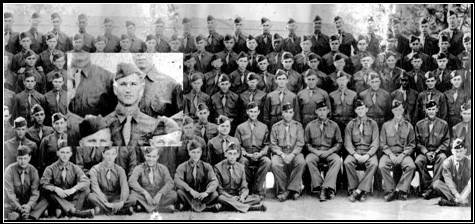

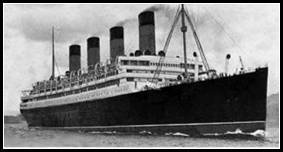

My

Basic Training Unit at Fort Benning, Georgia

In The ASTP

We completed the basic training phase the first week in December 1943

and I was happy to learn that I would be going to the

Alabama

Polytechnic Institute (API), in Auburn, Alabama (now known as Auburn

University) for the college training phase. API was a respected and

well-known engineering school and I had wanted to become a chemical

engineer some day. I was given a ten-day furlough and ordered to report

in at API afterward.

The train ride to Abilene took

In The

Infantry

Deployment to the European

Theater

When I returned to Atterbury, we were in the final

stages of training and

early in October 1944, the Division was ready for

deployment. We went to

Camp Myles

Standish, near Boston, to prepare to ship out for Europe. My

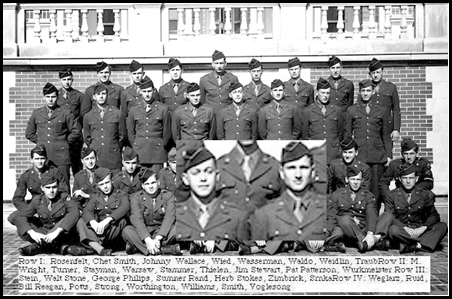

regiment, about 9,000 men, along with various support units boarded the

Aquitania, an old World War I era British passenger liner, that had been

converted into a troop ship for the war. The ship was originally built

to accommodate approximately 3200 passengers, but carried more than

10,000 troops. About 20 of us were packed to a stateroom that had been

built to accommodate two passengers in peacetime. In addition to our

bodies, we had find space to cram our clothing and other gear. We slept

on canvas bunks stacked six high, about eighteen inches apart.

The HMS Aquitania

After an uneventful crossing of about 6

days, we arrived in Scotland late in October at Greenoch, a small port

city on the Firth of Clyde. We loaded our gear onto barges and I rode a

barge up the Clyde River to

Glasgow. We were

there few days while our gear was transferred from the barge onto a

train. A thick fog made it impossible to see much of the town. The only

thing that I remember about Glasgow is that one night I went to a

political gathering of some sort and listened to a couple of guys debate

about something in their Scottish brogue and left wondering what they

were talking about.

Brief Stay

in England

We soon boarded a train for an overnight

trip to Cheltenham Spa,

a town in the Cotswold region of England. We were housed in

Quonset Huts on

an estate called Guiting Grange for a few weeks while waiting for our

vehicles to arrive by ship from the States at the port of

Liverpool. While we

were there, I got my first promotion – from a “buck private” (no

stripes) to a “buck corporal” (two stripes) – and was proud of it. My

pay went up from $50 per month to $65 per month - a 30% increase, and

percentage-wise, the largest pay raise I ever received.

I was sent

to Liverpool with a group to pick up our vehicles. Soon after we

arrived, a fog came in so dense that we could see only a few feet in

front of us. We stayed there an extra night. The next day it looked like

it wasn't going to lift, so we decided late in the day to head back to

Cheltenham. We formed a convoy and drove all night in "black-out"

conditions, and even though the fog stayed us with the whole way, we

managed to get back to Cheltenham without a single rear-ender. It was

late in November, but we were finally ready to go into action.

Arrival in

France

We left

Cheltenham and headed for Southampton on the southern coast of England

near the English Channel. I was driving a radio section

jeep with the assistant

regimental communications officer, CWO Tom Holland, as a passenger. When

we reached Southampton we spent the night and late the next day I drove

the jeep onto an

LST and

after an overnight trip across the English Channel, we arrived in the

harbor at LeHavre, France. Le Havre had been heavily damaged during the

D-Day

invasion and the harbor was in bad shape, but I was able to drive the

jeep off of the LST and onto the beach without any trouble. From

LeHavre, we drove a few miles to an abandoned chateau where we

bivouacked on the grounds for two days while waiting for the rest of our

regiment to arrive from England.

At the French Chateau

Hurrying Up While Waiting

With Squad Leader Ray Jones

The ground

was muddy from drizzle and intermittent rain, so we spent most the time

in the jeep trying to stay dry. That wasn’t too bad, but it sure wasn’t

very comfortable for sleeping. When the rest of the regiment arrived, we

formed a convoy and headed to Belgium to relieve the 2nd Infantry

Division, which had been in action ever since

D-Day. The weather

had been cold and rainy ever since we arrived in France, and it started

changing to snow and ice as we entered the Ardennes Forest region of

eastern Belgium.

The terrain

was hilly, and with ice and snow on the roads, the going was slow. It

took several days to get though the forest to the front and we had had

enough of trying to sleep sitting up in the jeep, so we decided to sleep

on the snow. We laid the windshield cover from the jeep on the snow and,

although we only had two blankets to use as cover, we managed to stay

warm enough to get some sleep. I served as a road guide the next day,

directing troops to their positions in the front line. We had not been

issued overshoes, so my feet were wet and cold the whole trip.

Arrival at

the Front We finally arrived at our destination on the 11th of December 1944 at Schlausenbach, a little farming village about 5 km inside Germany. It was near the Siegfried line, which had been started by the Germans before WWI and finished by Hitler in 1932. My radio squad moved into a two-story house, which had already been commandeered from its owners by a squad from the 2nd Infantry Division when they captured the town. For the first time in weeks, I had a bed to sleep in, but my feet hurt so much I couldn't really appreciate the luxury. The next morning, my feet were so swollen I couldn't get my boots on so Sgt. Battrick, the platoon sergeant, sent me back to a collecting station for treatment.

The Bulge

Begins

The date

was December 16, and the explosions were the beginning of a two-hour

barrage of artillery fire that marked the start of the last major

German offensive, better known as the “Battle

of the Bulge”. The barrage started around 5:30 and soon after

daylight, a close friend, Irvin Roger, stopped to see how I was doing

and told me the Company was under heavy attack by the Germans. He was

driving a message center jeep and was on his way to the 106th Division

Headquarters in

St. Vith

with information about the attack. It wasn’t long until we began to hear

rifle and machine gun fire as well as the artillery fire as the fighting

moved closer to Schönberg.

Around noon, the medics at the collecting

station were ordered to load the patients into ambulances and move them

back to St. Vith. There weren’t enough ambulances for everyone, so

anyone who could walk at all, which included me, was told to find a ride

or head for St. Vith on foot. About that time, Irvin Roger stopped by.

He had been on his way back to the 422nd Regimental HQ in

Schlausenbach, but the Germans had blocked the road and he couldn’t get

back to the company. So I got in his jeep and luckily for me, he had

found a pair of arctics and brought them to me so I put them on and we

took off for St. Vith.

We got there early in the afternoon,

reported in at the Division HQ, but there was a lot of confusion and we

waited the rest of the day, expecting someone to tell us what to do. We

were still there when it got dark, so we bedded down on some benches in

a hall and spent the night. The next morning we still hadn't been told

what to do, so we left the building to look around town to see what was

going on. There was a convent near the headquarters building with a tall

brick wall around it. We saw an American Sherman tank parked next to the

wall and stopped to talk to the crew. They told us that they were part

of a Combat Command from the

7th Armored Division that had been sent to St.Vith to provide

armored support for the 106th Infantry Division. Things were pretty

quiet, and while we were talking, we saw a good looking Belgian girl in

some tight-fitting ski pants walk down the street and go into a large

stone house on the other side of the street.

Roger and I decided that we

probably should try to get acquainted with her, since we had parked

Roger’s jeep right in front of the house.

Under Fire

As we

started to cross the street, there was a loud explosion, scaring the

hell out of us. It was from a shell fired by a German tank that was on a

ridge just east of town. Apparently, the tank was a lead tank of a

German assault force that was scouting out the town and when the crew

saw the 7th Armored tank parked by the wall of the convent they decided

to take a shot at it. When we parked our jeep in front of the house we

had noticed that it had a side entrance going into a basement, so we

made a beeline to the basement for cover.

We had "rescued" a

Bazooka that we found

unattended at the Division HQ, but had left it in the jeep.

Soon, there was a lull in the shelling, so we ventured out of the

basement to get it. When we got to the street, however, we saw a member

of the tank crew lying on the ground, obviously in pain. We ran across

the street to see if there was anything that we could do to help him. As

it turned out, he had been hit in the rump by a piece of shrapnel, so we

ran back across the street to get the jeep and see if we could find a

medic. When we got to the jeep, we saw a big hole in the hood right over

the engine. We raised the hood to see what damage had been done, and saw

that a big piece of shrapnel had gone right through the block. We looked

to see where the shrapnel had come from and saw that the shell had hit

the house right above where we had parked. While we were standing there

trying to figure out what to do, someone started shooting at us from

down the street. We assumed

that it was a sniper, so we ran back to the basement to get Roger’s

rifle so we could return the fire. When we came back out, the sniper had

disappeared and an ambulance had arrived to pick up the wounded tanker.

The German

tank had also stopped firing and disappeared, so we went back over to

the Division HQ building, where we learned that they were getting ready

to move back to the town of

Vielsalm, about 10 km to the west of St. Vith. We were told to get

back to Vielsalm as soon as we could and report in to the personnel

officer for re-assignment. We had seen a couple of other guys from the

422nd driving a message center jeep, so we took off to see if we could

find them. We found them, got in their jeep and were just about to take

off for Vielsalm when a couple of commissioned officers showed up,

ordered us to get out of the jeep and took our seat, leaving us without

a ride to Vielsalm.

Becoming a

Straggler We had seen a supply depot in town, so we went there to see if we could find a ride. While we were there, we liberated couple of carbines. I had left my M-1 rifle with my other stuff back in Schlausenbach, and Roger thought a carbine would be easier to carry than a rifle. We also liberated a small kerosene space heater and I found some really warm, English-made woolen socks I requisitioned to wear with my arctics.

After we had eaten, he drove us to the to

the 422nd Division’s rear echelon personnel office and we reported in to

the personnel officer (Lt. Mel Crank), who told us to told us to stow

our gear, then come back and take charge of setting up a defense

perimeter around the buildings that housed the rear echelon units. We

acted like we knew what we were doing, and soon had the personnel clerks

digging

foxholes all over the place. We checked on them from time to time

during the night, and in the course of doing so, we discovered that Lt.

Crank had just received his monthly liquor ration and left it sitting

out on his desk. We decided that after what we had been through, we

probably needed it more than he did, so we "rescued" a couple of bottles

for our own personal use. There will be more said about them later on.

Life as a

Straggler

The next

day, an officer from an artillery unit rounded up all the stragglers

that he could find to form a defense perimeter that he was setting up

around Vielsalm. A “straggler” was a soldier who was separated from his

unit and was susceptible to assignments by anyone with a higher rank.

Roger and I were told to man a 37 millimeter antitank gun and use it to

help defend against the German tanks that were headed our way. It would

have been be like fighting against the German Tiger tanks and their 88

mm guns with a peashooter. We didn’t even know how to fire it, but as

things turned out it didn't make any difference since the Germans were

delayed trying to take St. Vith and didn’t reach Vielsalm that day.

The day before St. Vith fell to the Germans (which I think was 23rd of December), combat engineers had placed explosive charges on a railroad bridge that passed over the road from Vielsalm to St. Vith so it could be blown up to block the road when the last of our tanks that were retreating from St. Vith had made it through the underpass.

Someone had already dug some foxholes on the

top of the railroad embankment and the other guys got in them, but I

decided to

try and get some sleep while we waited

for the American tank columns.

I got in my sleeping bag and lay down on the ground near one of the

foxholes and had just dozed off when an artillery

shell hit

the embankment and exploded somewhere close to where I was sleeping. I

started rolling toward my foxhole, or so I thought, but I rolled the

wrong direction and rolled all the way down the embankment. As soon as I

stopped rolling, I got out of my sleeping bag and yelled at Roger to see

if he and the others were okay (they were), and scrambled back up the

embankment and got in my foxhole just as another shell exploded. It

wasn’t as close, but the shelling

continued intermittently all night. The shells must have been coming

from some heavy artillery, because the shrapnel was large enough to cut

through the trunks of some large pine trees near the embankment, and we

could even hear them coming in before they hit. Fortunately, Roger had

brought along one of the bottles of whiskey that we had liberated from

Lt. Crank’s desk, so we passed it around during breaks in the shelling,

trying to shore up our spirits.

Shortly after daylight, some guys from the 82nd Airborne Division came

up relieved us. In contrast

to us, they seemed to know what they were doing, so we were more than

willing to turn the job of blowing the bridge over to them.

We hitched

a ride back to Vielsalm on one of the trucks retreating from St. Vith,

and found the Division's rear echelon loading up to move further back

from the fighting. Our next stop was in the town of Ferriere, 10 km or

so west of Vielsalm. I won’t forget that place for several reasons. One

was that some 55-gallon barrels had been elevated on a wooden platform,

fitted with short lengths of rubber hose and filled with hot water to

serve as makeshift showers. It was my first opportunity to take a shower

since we left the Cheltenham area in England, almost a month earlier. I

was wearing the same smelly, dirty clothes and after taking a

much-needed shower, finally got into some clean ones. The swelling had

gone down enough in my feet that I was able to put on some boots and

toss the arctics.

Another reason for remembering Ferriere was

that the weather had been bad all week, but the skies cleared on the day

before Christmas and I watched several formations of B-17 bombers

heading toward Germany. There were puffs of black smoke as

flak from the German 88 mm anti-aircraft guns bursting all around

them. Some of the planes turned into big orange balls of flame when they

suffered direct hits. Others started spiraling down when the flak hit

them and the crews could be seen bailing out. I had always sort of

envied the “flyboys” with their snazzy uniforms and cushy life, but from

that day on, I wasn't the least bit envious of them and didn't have

anything but good to say about them.

A Memorable

Christmas

The

Division HQ rear echelon’s next stop was Lince-Sprimont, a small town

near Liege. Roger and I had not been re-assigned to a unit, so we went

with them, still on foot. It was Christmas day, December 25, 1944. As we

walked into town looking for a place to sleep, we saw a young girl and

asked her if she spoke English and whether she knew of anyone that might

let us sleep in their house. She did, and led us down one of the narrow

streets to a small house that was built over a cowshed. She introduced

us to Angelique and Nicholas James-Gilsoul, an old couple, who greeted

us warmly. The girl told them that we were looking for a place to sleep

They didn’t speak English and we didn’t

speak French (the language in that region of Belgium) but we all enjoyed

trying to carry on a conversation. They both could speak a little German

and Roger could speak Yiddish, which is similar to German, and using

that knowledge along with a lot of gestures we did pretty well. Whenever

Angelique referred to the Germans, she used the term “Boshe”

so derisively that it was obvious that she didn’t have any love for

them.

They had a radio that picked up a short-wave

broadcast from a station in

Andorra (a tiny

country between France and Spain in the Pyrenees Mountains) that had

both French and English-language newscasts.

It was our first opportunity to hear any news from the outside

world in several weeks. We listened some “news” about the Bulge by “Axis

Sally” and “Lord

Haw-Haw”, a couple of English-speaking German propagandists. That

night, we listened to the put-put of “buzz-bombs” (German

V-1 rockets) as they came over us heading for Liege. Occasionally,

their motors cut out, which meant that they were staring to descend, and

within a minute or so, there would be a loud explosion when they hit the

ground. It was a bit nerve wracking because we never knew where they

were going hit and explode. Fortunately, none of them hit the town.

It was the most memorable Christmas

day that I have ever spent.

My mother saved the letter that I wrote her that night.

It begins with “ Dear Mother, “This is Christmas night and I

couldn’t let it pass without writing you.

Everything that happens that reminds me of Christmas reminds me

of home . . . . .

Transfer to

106th Signal Company

While we were

still there, Lt. Crank told Roger and I that we were being re-assigned

to the 106th Division Signal Company. Carl (Pat) Patterson was a radio

operator in the company who was a friend from my ASTP days at Auburn so

he, Roger and I formed a 3-man team to provide radio communications

between the 106th Infantry HQ and one of the infantry battalions in the

424th Regiment. The German

advance had been halted by the first week in January and the battalion

joined several other American and British fighting units in an effort to

drive the

Germans back to where they were at

the start of the offensive.

Seeing the

Effects of War

Around the

middle of January the battalion pulled into the town of

Stavelot. right

after the Germans had been driven out. There were a lot of burned out

German tanks, half tracks, and Volkswagen jeeps in the town, several

with dead German soldiers in them, some still at their guns. A

particularly gruesome sight was a burned out Volkswagen jeep with the

bodies of two men still in it, one burned so badly his head looked

something like a burned porcupine with

Our next

stop was in the town of Hunnigen, a small town in the German-speaking

region of eastern Belgium. Now, to give you an idea of how inconsiderate

soldiers can be during times of war, I'll relate a tale that I’m not

very proud of. When we learned that we would be spending several days in

Hunningen, we found a house that was in pretty good shape except for one

corner that had been blown off by a tank shell. We wrapped a tarp around

the corner to block out the cold, and settled in for what looked like

what might be a few of days of living in some fairly comfortable

quarters. There was a wood-burning stove in the main room, but the only

wood we could find was the wooden floor of the house, so we took an ax

and chopped up part of the floor for use as firewood.

I don't think that it ever occurred to us that the house belonged

to a Belgian family that would want to move back into it once the

fighting was over in the town.

A couple of days after we had taken over the house, a man and his

wife and a couple of children showed up and the woman took one look at

what had happened to her house and started crying. Between sobs, she

kept saying "mein haus, mein haus!" I don't think I have ever felt so

sorry for anyone in my life, and I still have feelings of guilt when I

think about it.

Back to the

422nd Infantry Around the middle of March, before we got to the Rhine River in Germany, the remnants of the 106th Division (mainly stragglers, the two battalions from the 424th regiment and various headquarters units) were pulled out of the fight and sent back to St. Quentin in France to re-group. While we were there, I got a 3-day pass to Paris It was one of the highlights of my stay in Europe. I toured the city, had some excellent meals, went to the Folies Bergère and a concert by the Glenn Miller band (Miller himself, had just been classed as “missing in action” when his plane disappeared on a flight from England). I learned to get almost anywhere I wanted to go on the Metro, the French subway system.

Celebrating

Victory in Europe

One of my

main memories of that experience was driving into the city of Nantes in

an open jeep with some buddies on

V-E day

and being treated like conquering heroes. We ended up so stoned on green

wine that none of us could remember how we managed to get back to camp.

I'll never forget the hangover that I had the next day when I came out

of my stupor. We stayed

around there long enough to accept the surrender of Germans who had been

holding out in the two pockets, taking their guns and herding them into

boxcars for shipment to prison camps in Germany.

We

completed that job late in May, so we loaded back into boxcars and went

back to Germany to get ready to go to the Pacific and have it out with

the Japanese. I don't

remember just where we got off the train and picked up our vehicles, but

I do remember driving a jeep across a

pontoon bridge over the Moselle River at

Koblenz. The city was

mostly rubble from repeated attacks by American and British bombers. The

rubble was still being cleared from streets by bulldozers when we went

through. There were thousands of “displaced

persons” in and around Koblenz, many of them living in camps along

the Rhine River and many were near starvation. When we were on the road,

our meals were prepared in field kitchens and served in mess kits. There

was always a bunch of such people waiting by the garbage cans asking us

to dump everything that we had not eaten into their containers instead

of the garbage cans. Needless to say, we were more than glad to do so.

Training

To Go To The Pacific

Camp Allen W. Jones

Parting

Company

strip near the town of

Dole, France,

teaching in a radio school. Dole was famous as the birthplace of Louis

Pasteur, the chemist who developed the art of pasteurization. While I

was there, I had

the

opportunity to visit well known cities that were nearby,

Besançon,

famous for its wine and

Dijon, famous for its mustard.

.

Final

Assignment

After a

month or so in Dole, I was transferred to a military police unit in

Nancy, France. I was

member of a three-man crew, operating a dispatch radio at the MP

headquarters. It was truly an ideal assignment. We worked eight-hour

shifts, so when my shift was over I was free until it was time for the

next shift. Nancy was a fairly large city with an interesting history,

some beautiful plazas and lots of culture. I was billeted in an old

French army caserne near the center of town and there was a small French

bakery nearby. I liked their bread and pastries and one day when I

stopped in to buy some, the owner’s wife introduced me to her daughter.

Her name was Fernande, a very attractive eighteen year old who had just

returned home from a Catholic convent where she stayed, going to school

during the German occupation. She spoke fluent

Around the first of December I finally accumulated enough points around to return to the states and went to Camp Philip Morris, one of several "cigarette camps" that had been set up near LeHavre to process GIs for their return.

The hatch covers got so slick with vomit that we couldn’t

keep our feet under us, and can you imagine how relieved we were when we

finally arrived, safely, in New York harbor.

There, we

boarded a train to Camp Kilmer, New Jersey, where we spent a few days

being processed. I boarded another train and went to

Camp Fannin, near

Tyler, Texas where I received my official discharge from the Army on the

23rd of February 1946. And since I was no longer a

I regret

not having kept a diary or a journal while I was in the service. I have

always had a problems remembering details, so what I've ended up with

are mostly general recollections of some high spots. I do remember that

I never killed anyone, enemy or friend. In fact, only time I seriously

thought about shooting at anyone was when Roger and I thought that

someone was shooting at us in St. Vith. I have had access to letters I

had written to various members of my family, but since we were limited

in what we could tell about where we were or what we were doing, they

don't provide much information about what I had done, seen or

experienced during the war. My hope is that this brief, and admittedly

general, account of my experiences will be of some interest to my

children and their descendants.

Herb

Stokes, April 2011 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Page last revised

10/23/2019 Page last revised

10/23/2019James D. West www.IndianaMilitary.org jimdwest@centurylink.net |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||