|

Sixty Years of Peace in Grosslangenfeld Saturday, 12.16.1944

and Sunday 12.17.1944 of the 190th Grenadier Regiment:

16-18 December, 1944

What Really Happened at Grosslangenfeld, Germany December 16-18, 1944 Lt Joseph C. Haines 2nd Platoon 106th Recon Troop

German Account of the Battle for Grosslangenfeld 16-18 DECEMBER 1944 The official history of the 62nd Volksgrenedier Division by Leutnant Gerhard Wurms |

|

Saturday, 12.16.1944

and Sunday 12.17.1944 Contributed by Josef Reusch and Sebastian Pusch |

|

Silent footprints in the falling snow betray a grim column of ghosts, bleeding west through the low southern neck of the narrow Alf valley and slowly blanketing the south-western corner of the �Schnee Eifel.� Still dark at this early December hour � just past fifty degrees northern latitude � German artillery punctuates the crisp morning air in Grosslangenfeld, a small farming village near the center of the Bulge saddling the ridge southwest of Bleialf. Several kilometers to the south, Josef �Jupp� Reusch, a native of the village and a seventeen-year-old conscript fresh from artillery training in Norway, is crossing into Luxembourg near Tintesm�hle with the 560th Volksgrenadier Division...

As the mental echoes of sixty-year-old artillery fade, Josef, his daughter Anita and an American son-in-law follow the faded tracks of German 6th Panzer tanks over the Our river past Sch�nberg on the morning of December 16th. Navigating icy memories and clinging fog, they join a large procession of hundreds of Belgian and German officials, soldiers and Bulge veterans with their families in B�llingen, to commemorate the fallen soldiers whose memory endures in numerous monuments honouring their individual and collective sacrifices.

Counting several veterans of the Golden Lion � fellow survivors � as comrades today, Josef was determined to act on a long-held desire in the weeks leading up to the 60th anniversary of the Battle of the Bulge: to create a monument in Grosslangenfeld offering due respect to all who perished in his village during the war.

Intended not as a memorial to war or glory, the uncomplicated �naturstein� design bears no overt symbolism, only a simple message in German explaining which units engaged and the loss of life and property sustained. Ultimately, its real value to posterity is the blunt historical reminder to current and future generations of the heavy toll war exacts on all involved.

Grosslangenfeld�s location, sandwiched between one of the most famous man-made landmarks of the war � Siegfried�s �West Wall� � and the natural barrier of the �Schwarzer Mann� on its eastern flank, also places the new stone within a vast historical context spanning over two thousand years. The Eifel is a region far too familiar with war, World War II marking only the final phase of five centuries of steady conflict surging back-and-forth through the windy hills and verdant valleys of the ancient Rhenish slate plateau.

Bounded on the north, east, and south by the famous Ahr, Rhine and Mosel rivers, the Eifel first appeared in recorded history when Julius Caesar arrived in 54 B.C. with four legions, confronting the distinct Celtic culture of the �Treverer.� They and the Germanic �Eburonen� to the north were pacified and intense Romanization of the lands between Trier � �Treveres� in the roman lexicon � and Cologne began. When Franks occupied the Eifel by the middle of the 5th century most romanized Celts fled, and with them the remains of roman culture.

The Eifel was the favorite hunting ground of Emperor Charlemagne in the 8th Century, whose empire was fragmented by his sons, triggering a long period of violent division as local lords also quarreled, raising over 140 fortresses by the 12th century. Such fragmented power offered easy prey to four large surrounding powers, Kurtrier (Trier), Luxembourg, Kurk�ln (Cologne) and J�lich, but the scale of battle had not yet impoverished the locals. Diverse agriculture still produced enough food for self-sufficiency. Mining of basalt, iron and lead permitted modest trade. When monk Sebastian M�nster wrote a glowing description of the Eifel in 1541, he could not know he was capturing its last peaceful moments.

Beginning in 1542, internecine conflict between the predators on the perimeter turned the region into a near-permanent battleground. Armies settling in for the winter meant misery for local farmers and trade in the region eventually collapsed. Ravaged by the Thirty Years War, a starving population was nonetheless expected to provide food for every invader. In one chronicler�s telling description, agriculture had ceased to exist and once-prosperous livestock were wiped out. People fled or starved to death. Whole villages disappeared.

In 1667, Louis the XIVth of France sought to annex the region by force. In 1672, the Dutch defense of the Rhine Delta pushed back, laying waste to the North Eifel and central �Hoch Eifel.� In 1688, after the Sun King�s armies again failed to reach the Rhine, he set out to raze the entire Rhineland-Palatinate. Over a thousand castles, forts, villages and towns were systematically levelled. With few exceptions, the once-abundant medieval jewels of Eifel craftsmanship disappeared into antiquity.

French revolutionary troops arrived in 1794, eliminating the old class system, granting civil rights and ending compulsory labor and onerous taxes levied by the cloisters and nobility. During the twenty-year occupation old Eifel industries found new markets. Quarries and mines took up large-scale production. Even today, fond memories of the French occupiers persist, as later Prussian influence was to isolate the region until well after World War II. Under the Prussian thumb, the area became an isolated borderland, its iron industry severed from traditional markets by new western boundaries. Neglecting to connect the remote region to a growing transportation network and new markets to the east brought economic ruin. Famine emptied the land and the Eifel became known as �Prussian Siberia.� World War I found the region a forgotten country; a white spot on the German map.

Which brings us back to a cold December morning and a certain stone in Grosslangenfeld, standing among the ghosts of centuries and dedicated in spirit to the sixty years of peace following the events it tacitly describes. A peace paid for with the lives of men honored by the memorial � and raised by a benefactor whose ancestors were no strangers to the sacrifices and struggles inherent in war.

Originally scheduled for the afternoon of December 18th, plans for the dedication ceremony shifted abruptly after a phone call out of the blue from a representative of the US First Armored Division. Just returned to Germany from a long tour in Iraq, he bore news that five of the now-famous �Band of Brothers� were heading for Germany to take part in the Bastogne events and extending an invitation to join them.

Unfortunately, poor organization and �security concerns� put an unceremonious end to our invitation to a coffee and breakfast welcome we offered to provide for the veterans in the local community hall on the morning of the 16th, as well as rescheduling our own dedication ceremony to suit their tight schedule. Sadder still, the invitation to join them was also rescinded later due to �budget issues� and �security concerns.�

What was at first a small contingent including the veterans had ballooned into busloads of soldiers arriving at 0700, rumors of Tom Hanks� possible presence with the veterans being leaked to the global press and a developing Army public relations exercise that ran contrary to the spirit we�d intended for the event. Though disappointed by the outcome, all breathed a collective sigh of relief when the event reassumed more normal proportions no longer involving the early morning feeding of so many hungry young soldiers.

December 18th arrived cold, windy and threatening snow, not unlike its counterpart in 1944. At exactly 1500, Josef�s wife Mia rang the church bells to signal the start of a short procession from the community house to the monument, including local citizens and the village�s volunteer fire brigade, in which Josef served for forty years. Several reservists from the Bundeswehr, including two in accurate period uniforms, were positioned at the monument, led by Josef�s good friend Lieutenant Manfred Klein.

The procession complete, a trumpeter struck up the German national anthem as the bells rang out and the black velvet shroud covering the memorial was lifted. The trumpeter then played a beautiful rendition of �Ich hatt� einen Kameraden,� a song traditionally played in honor of fallen comrades. (It is important to note that in German the word �comrade� doesn�t carry the same linguistic baggage as it does in English, referring simply to another person to whom one is closely bonded by shared experience � like a fellow soldier.)

As the final haunting notes drifted away on the wind, Mayor Erich Kribs spoke, emphasizing the importance of such a memorial to the younger generation, as a reminder of history that should not be forgotten. Herr Karl Kneissl, parish dean, read from 2nd Isaiah, echoing an ancient call for peace exhorting mankind to beat swords into ploughshares, before blessing the memorial. Josef then offered a sober recollection of the events of sixty years ago, even as the snow started falling again:

�The German charge was repelled by American defensive fire. Retreating and regrouping, they opened fire again later that morning. A part of the 164th Infantry Regiment joined in the attack from Wallerich. A second assault was successfully thwarted by the Americans, with heavy losses on the German side. The attack was relaunched from various locations and at different times in the afternoon, but the American resistance was unbeatable. The Americans sent wounded towards St. Vith in an armored vehicle, with orders to bring back ammunition. They never returned��

Retreating from the monument to the community house for coffee and sandwiches prepared by Mia and Anita � none of Mia�s famous cakes this time � everyone sat together talking and reflecting, Josef thanking all who had contributed their time and energy and expressing his happiness that the commemoration went off without a hitch despite the skittish weather.

Later, as the assembled friends and neighbors dispersed, a sharp ray of sun leapt through the leaden clouds and illuminated the new monument for several lingering seconds, the unexpected burst of brilliance triggering images of frozen soldiers ranging the steep wooded hillsides of the Schnee Eifel, their searching eyes turned toward a capricious Eifel sky.

# # #

Story and photos by Doug Mitchell w/English translation by Anita Reusch Gro�langenfeld, Deutschland January 2004

Contributed by John Kline, 106th Division |

|

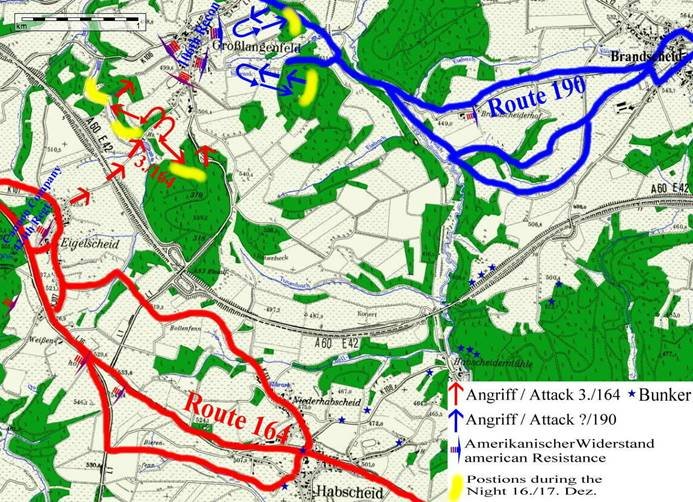

16-18 DECEMBER 1944 190TH RGM�T OF THE 106TH RECONNAISANCE TROOP 62ND VOLKSGRENIDIER DIV. DEFENDS GROSSLANGENFELD ATTACK FROM WEST

164TH RGM�T OF THE 62ND VOLKSGRENIDIER DIV. ATTACK FROM SOUTH |

|

WHAT REALLY HAPPENED AT GROSSLANGENFELD, GERMANY December 16-18, 1944 Lt Joseph C. Haines 2nd Platoon 106th Recon Troop Published Source: Bulge Bugle November 2002

Since World War II, I have read numerous accounts about the Battle of the Bulge detailing what happened to the various units positioned along the Siegfried Line between Belgium and Germany. None of these accounts that mention our 106th Recon Troop relate the truth about what really happened at Grosslangenfeld from dawn on December 16th until we pulled out the afternoon of December 17th.

Some of the �reports� I've read are � Colonel R. Ernest Dupuy�s book, St. Vith: Lion In The Way (reprint 1986, pp 50) states; "As the morning waxed, and the 423rd reports 16 December as �clear and cold,� it was evident that the enemy had taken Grosslangenfeld in the 424th Infantry sector.... As a matter of fact, we were still fighting in Grosslangenfeld until early afternoon on the 17th!! Then, on pp 55, Colonel Dupuy states; The 106th Reconnaissance Troop at Grosslangenfeld disintegrated, opening Cannon Company�s left flank.... The Germans actually advanced between the Cannon Company of the 424th Infantry and the 106th Reconnaissance Troop. We did not disintegrate! And, on pp 57; "Personnel carriers rolling in from Grosslangenfeld disgorged wave after wave of infantry..... Later, on pp 58, he mentions ....some infiltrating enemy from Grosslangenfeld... ALL of these statements are false!! The actual facts are that NO enemy troops or vehicles passed through Grosslangenfeld until mid-afternoon of the second day � December 17th!! These unsupported statements by Col. Dupuy are a gross insult to the men of the 106thReconnaissance Troop who fought valiantly in defense of their untenable position at Grosslangenfeld; completely cut off from other American Units, surrounded by the enemy, out of communication and nearly out of ammunition.

Unfortunately, these same untruths were repeated by Charles B. MacDonald in his book "A Time for Trumpets"; as well as being noted by several members of our Troop in various other so-called �official accounts� written about the Battle of the Bulge (titles and authors not specifically recorded).

The following account has been compiled from my memory of these days; plus, the collective memories of some of the survivors of the Troop with whom I have either talked or corresponded over the years: i.e. � Paul Thompson, Richard Bradbury, William O. Tower, Arthur LaCroix , Calvin Lezzi, Howard Hughes, Edward Fleming (one of four authors of �The Map�), Robert House, Earl Liston, Michael Gresh, Jr., Willis Selje, Kenneth Booz, Abraham Freund, John Simpson, Robert Fisher, Louis Cunningham, Rudy Aittama, Ralph Pope, Michael Liskiewicz, Bill Roub, Roger Frambs, Rishel White, and the late William W. Randall, Roy Mechling, Myron Johnstone, Edward McGee, Gene Hammond, Al Orzolek, Robert Madsen; plus, no doubt others I can't quite recall. The Troop was organized on 15 March 1943 (organic to the106th Infantry Division) and trained at Fort Jackson, South Carolina. Then participated in the Tennessee Maneuvers from January 20 through March 26, 1944.

From the Tennessee Maneuvers we moved to Camp Atterbury, Indiana, to complete our training for overseas movement. Beginning 9 October 1944, we moved to Camp Myles Standish, Massachusetts, for embarkation and shipment to the European Theater of Operations; and sailed on 10 November 1944 aboard the Wakefield. After an uneventful but rough crossing, we landed at Liverpool, England.

In England, we went by train to Stow-On-The-Wold where we received the rest of our authorized equipment, including brand new M-8 Armored cars complete with the very latest in radio equipment. After a short stay in England, we boarded an L.S.T. at Weymouth for the Channel crossing to Le Havre, France. Crossing the Channel, we encountered very rough weather. While anchored outside Le Havre Harbor waiting our turn to dock and unload, both anchors were torn loose and we had to return to Weymouth for repairs. After receiving new anchors, we repeated the crossing and a successful landing was made. After unloading, we proceeded by convoy at night across France to the vicinity of St. Vith, Belgium, arriving there on 9 December 1944.

We were attached to the 424th Infantry Regiment, and on 11 December 1944, we were placed on line during a night blackout move to replace a Rifle Company of the 23rd Infantry Regiment, 2nd Infantry Division. Our orders were to replace the Rifle Company - man for man, gun for gun.... Plus, we were ordered to maintain complete radio silence; dismount our .30-caliber machine guns from our vehicles; hide the vehicles in various buildings in the 0�Љ�U0�Љ�U�͉�U��U��Љ�UP�Љ�U@P�Љ�Uhe defense.

Note: At this time, the Troop T.O.& E. authorized � 6 officers; 149 enlisted men; 13 - M-8 Armored Cars; 99 - .30-caliber M-1 carbines; 13 - .30-caliber machine guns (light); 3 - .50-caliber machine guns; 30 - .45-caliber submachine guns; 5 - Rocket Launchers A.T. 9 - 60 mm mortars; 26 - .30-caliber M-l Rifles; 24 - l/4 ton trucks; 5 - M-3 halftracks; and 1 - 2&l/2 ton truck (mess truck)

We were positioned facing the Siegfried Line, with the 424th Infantry Regiment�s Cannon Company on our right (we could not see their nearest position to us) and Troop �B�, 18thCavalry Reconnaissance Squadron on our left (nor could we see their nearest position to us either). Most of our vehicles were placed where we couldn't readily utilize them. We had a full complement of officers and about 85% of our authorized enlisted personnel and attempted to man the positions vacated by the Rifle Company in Grosslangenfeld. We were forbidden to test fire our machine guns and 37 mm cannons on the armored cars, or to fire in our final protective line. We were ordered to use the range cards previously established by the Rifle Company so the Germans would believe the same Unit was still in place. There were no provisions for artillery support, or any other supporting fire for us. We were told this was a quiet sector or rest camp!! Since we were forbidden to use our radios, our only communication with other Units was a telephone line to the 424th Infantry Regiment. (It was years later that we learned all the other Units in the area had radio contact with Division.)

The only contact we could recall from the �outside� was the visit by a Red Cross Doughnut Mobile on the 13th or 14th of December that served us coffee and doughnuts, complete with music and the smiles of two American women!

At approximately 5:30 A.M. on 16th December 1944, we came under attack by German artillery, rockets, and mortars. This attack set fire to several buildings in the village, including my Command Post. The barn where our ammunition trailer had been hidden took a direct hit during the night of December 16-17, and our ammunition supply was destroyed except for the small amounts we had placed at various platoon positions.

Shortly after the initial shelling ceased, German infantry began to advance toward our positions in Grosslangenfeld. We were successful in repulsing them with small arms, machine guns, and 60 mm mortar fire; the mortar ammunition was soon exhausted. Later in the morning, another attack was mounted, and again repulsed, with heavy losses to the Germans.

During the shelling and early ground attacks, three of our men were seriously wounded � Sgt. Arthur LaCroix, T/5 Willis Selje and Pfc Robert House. Since our only medical service consisted of platoon medics, the Troop Commander decided to send the wounded to the rear. A halftrack was disarmed, and red crosses affixed to the sides, to transport the wounded to the nearest medical facility. Along with the driver, T/5 James Guthrie, volunteers Medic Abraham Freund and Supply Clerk Cpl. Howard Hughes accompanied the wounded. The volunteers were to deliver our wounded to a medical facility, report our situation, rearm, draw as much ammunition as they could transport and return to our position. They never returned. (Years later, it was learned they had successfully reached St. Vith, delivered the wounded (all survived their wounds), reported our situation, rearmed, drew a supply of ammunition, and attempted to return to Grosslangenfeld. Unfortunately, by the time they were able to begin the return trip, German troops had moved into the area between St. Vith and Grosslangenfeld.)

Shortly after the German attack began early on the 16th of December, our telephone lines were cut to the 424th Infantry Regiment. We were now out of communication with anyone.

The Troop Commander sent out mounted patrols to both flanks in an attempt to make contact with adjacent units (Cannon Company of the 424th and Troop �B�, 18th Cavalry). The patrol to the left flank returned to report they had made contact with Troop �B�, 18th Cavalry, and were told: We thought you guys were wiped out!!.... Heavy firing was heard on our right flank during this period, and the patrol we sent to the right flank (Cannon Company) did not return; nor did we receive a report from them since we were forbidden to use our radios.

Once the fighting started on the 16th, we uncovered our Armored Cars and began firing the 37 mm cannon at the attacking German troops. Since these guns were received new in England, we had never had an opportunity to �bore sight� or fire the guns � we accomplished the �bore sighting� firing at the enemy! The ground attacks and shelling continued off and on throughout the day of the 16th, but tapered off that night.

Early on the morning of the 17th of December, the enemy ground attacks and shelling resumed. We were successful in repulsing the ground attacks, but were running critically short of ammunition. Around noon on the 17th, the Troop Commander, Capt. Paul Million, called an officer�s meeting at his Command Post to discuss the situation and determine a plan of action. After reviewing the situation, it was determined that only two courses of action were available: one, to continue to hold our position until all ammunition was exhausted and be killed or captured; or, two, to break contact with the enemy and attempt to fall back to Sch�enberg where it was believed the Division reserve was located. It was believed if we could get back to contact Division, we could get updated on the situation, get supplied with food and ammunition, and receive new orders. Course of action two was adopted and orders (verbal) were issued that on a given signal we would break contact, one position at a time, and attempt to reach Sch�enberg to the north. The order of withdrawal was to be First Platoon (Lieutenant Edward McGee), Headquarters & Headquarters Platoon (Captain Million and Lieutenants George Vaream & Leonard Prosnick), Second Platoon (Lieutenant Joseph Haines), and, last, Third Platoon (Lieutenant Myron Johnstone).

Our withdrawal began shortly after 1300 with the First Platoon successfully breaking contact and withdrawing as planned. Headquarters and part of Headquarters Platoon then fell in line behind First Platoon and began their withdrawal. Second Platoon managed to break contact with two thirds of the Platoon intact and joined the withdrawal (the third section of Second Platoon was cut off by advancing German troops and unable to complete the withdrawal). The Third Platoon leader had arrived late to the officer�s meeting and either misunderstood the direction of withdrawal or discovered the planned route was now blocked by the enemy (I believe the latter to be the case); as he attempted to withdraw back the way we had initially entered Grosslangenfeld � from Winterspelt to the west and the area of the 424th Infantry Regiment. Their first vehicle in line was struck and disabled by a mortar or artillery shell thereby blocking the road (possibly by �friendly fire�, since it had been reported to others in our sector that �Grosslangenfeld had fallen� the previous day (on the 16th)). Lieutenant Johnstone was �slightly� wounded when a mortar shell exploded on the rail of his halftrack. The enemy was then able to quickly overrun those still remaining in Grosslangenfeld � which included the Third Platoon, parts of Headquarters Platoon, and the third section of Second Platoon. During this brief encounter of intensive fighting, several members of the Troop were killed or wounded. The wounded and other survivors were quickly taken prisoner and marched to the rear into Germany. However, one of our severely wounded men was carried to the German Aid Station by a buddy and received immediate and excellent care by the German medical personnel.

The sections of the Troop that managed to withdraw proceeded in a northerly direction on the paved road that ran through Grosslangenfeld toward Bleialf. However, attempting to avoid contact with the enemy, we decided to leave this major roadway and travel cross country, with the hopes of making contact with friendly forces. Shortly after leaving the paved road, we entered a deserted village (Winterscheid - in the 423rd Infantry Regiment area) where we stopped to put tire chains on our vehicles. Resuming our trek, we met up with elements of Troop �B�, 18th Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron at a crossroads just outside Winterscheid. They were really surprised to see us � they thought we had been �eliminated� the day before (December 16th). It was decided we would join them in the attempt to reach Sch�enberg. Troop �B�, 18th Cavalry, attached to the 423rd, had been given approval by radio to withdraw the day before - December 16th!! We were not aware of this decision, which left our left flank completely exposed.

We fell in behind Troop �B�, 18th Cavalry, and continued northward on secondary roads toward Sch�enberg. During our journey, we were under occasional artillery fire, including some tree bursts, until it began to get dark. We stopped on a wooded knoll just short of Sch�enberg to confer with the officers of Troop �B�, 18th Cavalry. After a short conference, it was decided we would break up into small groups and attempt to infiltrate the lines west toward St. Vith and get back to what we hoped would be American territory.

We disabled our vehicles, guns, and radios; then walked a short distance into the woods to what appeared to be a woodcutter�s shack. It was then decided we would spend the night here and see what the situation was in the morning. Just after daylight on 18 December 1944, we were nudged awake by German troops holding submachine guns and rifles and told we were now prisoners of war and the war was over for us!! (Note: I read one story that stated ...they surrendered to a group of 14-year-olds without firing a shot.... I wonder if the author of that statement ever looked into the muzzle of a �Burp Gun� and asked the soldier holding it.... �how old are you??�)

The greatest irony of all is the fact that the 106th Cavalry Reconnaissance Troop was deployed as Infantry (replacing a Rifle Company in the defense) prior to any combat activity in the area. And, we fought as Infantry � although we had not been trained or equipped as Infantry � yet, we were not considered eligible for the Combat Infantry Badge. Nor, have we ever been considered for any of the other medals or accolades deservedly heaped onto all the other Units in the area on that day that did their duty exactly as we did because of all the inaccurate and misinformation recorded about us in so-called �official� records!!

I have had no contact with anyone from the Troop who said they had ever been interviewed �officially� about what we did or did not do during this period of December 16-18, 1944, at Grosslangenfeld!! After my release as a prisoner of war, I was �debriefed� by being asked these 3 questions; Did you see any acts of heroism by any member of your Troop (this was the point at which I related the �act beyond the call of duty� performed by S/Sergeant Roy Mechling (one of the four authors of �The Map�) at Grosslangenfeld; recommending he be awarded the Silver Star for his bravery. On 16 May 1996 (about 52 years later!!), S/Sergeant Mechling was finally awarded the Bronze Star Medal with �V� device in an appropriate ceremony at Fort Jackson, South Carolina.)....did you see any cowardice by any member of your Troop (I answered, ABSOLUTELY NOT). Were you treated in a humane manner while a prisoner of war....!!!

This account as written is the truth of what really happened, and to prove the 106thReconnaissance Troop did not disintegrate on 16 December 1944. |

|

ACCOUNT OF THE BATTLE FOR GROSSLANGENFELD � 16-18 DECEMBER 1944 The official history of the 62nd Volksgrenedier Division by Leutnant Gerhard Wurms

Allerbesten Dank f�r die �bersetzung geht an Erich Craciun...Very best thanks for the translations goes to Erich Craciun...

The 15th / 16th December moves closer. These are days we soldiers will never forget, can never forget. We spend the night full of uncertainty in the local church. At approximately 4:30 the regimental commander gave us our orders. Then our artillery tore the silence of the night with loud salvos. An enormous reign of fire fell on the American lines. Searchlights lit up the night and illuminated the paths of the attacking grenadiers. With the course of time, the opposing fire became stronger. We are waiting for our orders to attack, which we received later. Only isolated American artillery fire goes up, to which we hardly take notice.

Again the official History:

The "Ardennenoffensive" did not bring the hoped-for success. Apart from me, I have only met one surviving member of the company, Josef Graf, who was captured around noon of December 17th. In conversation with other comrades of the division, I learned years after the war, that our company was up to 90% destroyed and was sent to break the toughest resistance faced the hardest fighting in the bataillon�s area. The defenders of the town were outnumbered and already shattered by our artillery fire. Nevertheless they fought bitterly and held out beating back the attack of 2 full companies. To these American soldiers I can only pay my fullest respect. |

| Page last revised 12/01/2005 |

|

|

_small.jpg)

_small.jpg)

-Trumpeters_small.jpg)

Page last revised

06/13/2015

Page last revised

06/13/2015