|

ON THE JOB TRAINING |

||||||||||||||||

|

An Oral History of the and of the Fate of Those Who Survived The 589th Group

© 589th Group 1999, Elliott Goldstein, Agent

Introduction

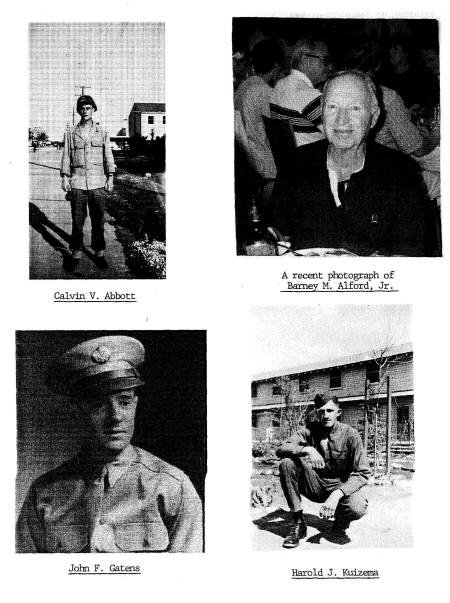

I was a major, assigned as Colonel Kelly’s executive officer, and I was struck by the fact after reading his article that we had been in two different wars after the first days. He thus encouraged me to write my story. With help I was able to secure a copy of the after action report that I prepared following the battle, which was eventually filed in the War Department Archives. But when I commenced work, I realized that my memories had faded. At that time John P. Kline, editor of The Cub, asked for comments on an article entitled “Parker’s Crossroads, The Alamo Defense”; the article and the comments were published in The Cub, (volume 3, number 3, pp. 15-36). I thought that if all of those who participated in The Cub article pooled their recollections, we could paint the picture of the action as viewed from the ground by those who fought in it. Of course, we could not enlist everyone, but the eleven who joined in this effort provided a story more complete than any previous account of the battle at Parker’s Crossroads. What I planned as my recollections became a much greater work, a realistic picture of combat as seen by each individual. I acted as the scrivener who put the work together, but each of the persons mentioned below is, with me, equally the author of this history:

Calvin V.

Abbott John C. Rain John F. Gatens Earl A. Scott Charles F. Jacelon Bernard C. Strohmier Harold J. Kuizema Frank Tacker Randolph C. Pierson

Their biographies are appended, and their later history is contained in Part II, of which Randolph C. Pierson was the scrivener. In addition, we have quoted from the reminiscences of Captain Arthur C. Brown, now deceased, and from a letter of Lieutenant Colonel (Ret.) Olin F. Brewster, which was published with the article, “Parker’s Crossroads: The Alamo Defense,” for which we thank him. We are also indebted to Robert C. Ringer, then a first lieutenant commanding the Ammunition Train of the 591st Field Artillery, for his report on the eleven men from Service Battery of the 590th Field Artillery who joined us at Parker’s Crossroads. We are deeply indebted to the late Francis H. Aspinwall, the battalion historian, who spent many years researching and writing the history of the 589th Field Artillery Battalion. This work was relied upon by John R. Schaffner as a source of additional information for use in composing his narrative. We also thank John P. Kline, editor of The Cub, for his help and encouragement. Special thanks are due Ms. Asta Moore, my administrative assistant, who assembled the work, proofread and edited it. This could not have been done without her. Elliott Goldstein Lt. Colonel Field Artillery (Retired) Former Executive Officer, 589th Field Artillery Atlanta, Georgia This Historical Event Is Recorded IN MEMORY OF Those Courageous Soldiers who Paid the Supreme Price and DEDICATED TO All the Brave Men who Fought Valiantly to Defend the Crossroads at Baraque de Fraiture, Belgium December 19 through December 23, 1944 during the Battle for Parker’s Crossroads

105 Howitzer Monument at Baraque de Fraiture

Translation by Henri Rogister of plaque at front of howitzer:

On the initiative of CRIBA and the Commune of Vielsame This Area of Memory Provided with a 105mm – 1941 - Howitzer gun, Dedicated to the United States of America and to their valorous combatants Was inaugurated on 7 May 1994 On the occasion of the 50th Anniversary of the Battle of the Bulge.

It is enriched

with the monument erected to the memory of By the Lion’s Club – High Ardennes in 1964 Foreword

Three defensive holding actions by American soldiers halted the German military in their efforts to go through Belgium to Antwerp, severing the American supply route. One was the defense of Bastogne, remembered by the reply of “Nuts” by the commanding general of the 101st Airborne Division to a demand for surrender. A second was the defense of St. Vith, by elements of the 106th Infantry, 28th Infantry, 7th Armored, and 9th Armored Divisions. This defense caused the German High Command more problems than the defense of Bastogne. The third--and the subject of this work--was the defense at the strategic crossroads at Baraque de Fraiture, Belgium. It received no publicity, and only after the records of both the German and American armies became available to historians was the real importance of that defense known. To those who were there, the battle is indelibly engraved in their memories, and they now know the importance of their stand. This work, written by men who were there--all non-professional soldiers with no previous combat experience--tells the story of the defense as seen through their eyes. While the story of every participant is not included, those which are, when taken as a whole, give a truer picture of the battle which took place at Baraque de Fraiture. As a tribute to Major Arthur Parker, who commanded the defenders until he was wounded and evacuated, the crossroads are known as “Parker’s Crossroads.” This is his story, and the story of all the brave men who delayed the advance of the German army from December 19th to December 23rd, 1944. It is followed by an oral history of the survivors, of which I was the scrivener. Randolph C. Pierson Captain, Field Artillery (Retired) Technical Sergeant Headquarters Battery 589th Field Artillery

Monticello, Florida

PART ITHE BATTLE FOR

PARKER’S CROSSROADS Table of Contents

CHAPTER 1The German Attack and the Retreat to St. Vith

One of the most extraordinary engagements of World War II was the blocking action by a part of the 589th Field Artillery Battalion, 106th Infantry Division, at Baraque de Fraiture, Belgium, also called Parker's Crossroads. The battered remnants of a field artillery battalion, with no infantry training and only the combat experience gained when they were attacked at the beginning of the German advance into Belgium, delayed the advance of a German Army Corps for five days, permitting the Allies to regroup and stop the German advance short of its objective. Pooling their memories to give an accurate account of what transpired, these members of the 589th hope to show what American soldiers can accomplish under the most dire of circumstances. After a relatively brief staging period in England, the 589th Field Artillery Battalion, with the remainder of the 422nd Infantry Combat Team, landed at Rouen, France on December 5, 1944, combat loaded. The average age of the enlisted men was twenty-one. After one day in bivouac, the battalion moved across France and Belgium into Germany and went into position a few miles east of St. Vith, Belgium. Having never before been in combat, the officers and men of the battalion had no knowledge of what to expect, or what they would be required to do when they eventually faced the enemy. Nor were they able to learn much during the eight days in position before the Germans attacked. On December 16, 1944, the German Army launched its last major attack on the Allied Forces. Driven back into the fatherland, the Germans had regrouped and prepared a drive designated to cut the Allied Forces in Belgium off from their supply lines, permitting them to repulse the Allied Forces on the borders of Germany. The path the Germans chose, through Belgium, was one that they had used before, along the Schnee Eifel and through the Ardennes and the mountainous region of Belgium. The area they chose to attack was a twenty-two mile front defended by the 106th Infantry Division, a division with no combat experience, which had been ordered to relieve the 2nd Infantry Division in its position at the Siegfried line. The commander of the 106th Infantry Division was told that the area was one in which there would be little action, since the Germans were expected to attack in the area to the north near Cologne and Coblenz. However, the intelligence on which this assumption was based was wrong, as the 106th Division would soon find out. In combat--except for those in a headquarters working with maps--the center of the war is where the individual is located. His observations are limited by what he can see and hear. In this work these veterans of the 589th Field Artillery Battalion have put their recollections together to preserve an account of what transpired during the Battle of the Bulge. The narratives are set out in chronological order, beginning on December 15, 1944, with each of the narrators identified. In addition, excerpts from a privately published memoir by the late Arthur C. Brown are included. DECEMBER 15Arthur C. BrownFrom December 7th to 15th we proceeded to dig and settle into fixed positions. Our infantry occupied the German Siegfried line. As this fortification naturally faced away from Germany, our troops had to face the wrong way for proper protection. As the 589th Field Artillery was on the extreme left, with only a cavalry screen protecting our left flank, our outfit was extremely vulnerable. Our front was Hitler's choice and Eisenhower's "calculated risk." We were untried troops, with no combat experience, and with an impossible defensive position. We had replaced the 2nd Infantry Division, and while the 2nd Division troops took their home-made stoves out of the dugouts and carried them to their new positions, we were indebted to the men of the 2nd for some tips they gave us on how to run a war. As an example, these veterans told us that you had to split your eight-man gun crew into two parts. This maneuver allowed half the men to rest while the other half manned the guns, thus permitting continuous service of the pieces twenty-four hours a day. In training the situation of continuous action never occurred, and the training manuals did not bring up the technique. The manuals were probably written by people who also had no combat experience. John R. SchaffnerThe 106th Infantry Division relieved the 2nd Infantry Division, and we took over the positions of the 15th Field Artillery Battalion. They were in a position east of the town of Laudesfeld, Belgium, and about one and a half miles south of Auw, Germany. The battalion command post was set up in the kitchen of a substantial German house to the rear of the firing batteries. The firing batteries took over the dugouts and log huts vacated by the men of the 15th Field Artillery Battalion. The howitzers were put into the same emplacements dug by the 15th, and in some cases the guns were simply swapped, since it was easier than trying to extricate the pieces already in place. A Battery was placed on the south side of the road to Auw and B and C Batteries on the north side. There was much snow, and the drivers had big problems once they left the hard road. The snow made it almost impossible to move off the roads, which later had the effect of channeling the German attack down the hard road. Service Battery was sent into position a few miles to the rear, about four miles south of Schönberg, Belgium. We were told by the 15th Field Artillery men that we had come into a very quiet sector where nothing ever happened. They weren't happy about leaving, and when we saw what relatively comfortable quarters they were leaving, we didn't blame them. I shared a dugout that was roofed over with heavy logs and had a jerry-can stove, just like uptown. We had been able to register A Battery, and the battalion was able to commence fire on December 9. We were feeling rather secure since, after all, our Infantry was between us and the Germans. It sounded good to me. We were supporting the 422nd Infantry Regiment, which was occupying the first belt of pillboxes of the Siegfried line, which had been breached at this point the previous September. Our guns were firing during the night, but since visibility was poor, it was unobserved. Headquarters Battery crews reported being fired upon, and an enemy plane circled the area for an hour or more. Numerous flares were seen to the flanks of the battalion, and an enemy patrol was reported to be in the area. During this period most of my time was spent at various outposts near the battery position. There was nothing to report. (As to those facts of which I had no knowledge, I relied upon Francis H. Aspinwall's "History of the 589th Field Artillery Battalion," published on pp. 81-89 of The Cub of the Golden Lion – Passes in Review hereafter referred to as "Aspinwall.") Elliott GoldsteinNot only were the gun crews divided into a day and night shift, the entire battalion operated on that basis. As battalion executive, I worked the night shift and was in command during the night hours, and Lieutenant Colonel Thomas P. Kelly Jr., battalion commander, was in command during the day. The other headquarters officers were Major Arthur C. Parker, battalion S-3, Captain George Huxel, assistant S-3, and Lieutenant Joseph Cocke, S-2. Major Parker, a graduate engineer, and a reserve officer who had served on active duty for several years in the early thirties, was better qualified to run the fire direction center than I, so I was made battalion executive even though I was junior to Major Parker. Each of the staff positions of the battalion headquarters were divided between day and night shifts. Personnel of a field artillery battalion in a fixed position were on duty in the same manner as workers in a manufacturing plant on 12-hour shifts, one-half of the artillery personnel working each shift. Everyone had adjusted to his shift, the battalion had shaken down, and we felt quite confident that we were able to perform our duties in support of the 422nd Infantry. During our settling-in period, I reconnoitered the area and met a cavalry officer, Lieutenant DeJongh Franklin, an old friend from Atlanta. He was on reconnaissance and approached me in a scout car. He warned me that his 14th Cavalry Group was attempting to cover nine miles of undefended front. His scout car was lightly armored, and in the event of attack, he could only report and run. So I was warned. On the night of the fifteenth I was on duty in the fire direction center at battalion headquarters, in command of the battalion. I commenced receiving reports from forward observers that major traffic was moving in the vicinity of Auw and convoys were seen moving with lights. Telephone wires connecting the battalion with the infantry forward observers were cut, flares were observed, and German patrols were reported in the area. Intelligence should flow from the infantry regiments and field artillery battalions who are in contact with the enemy back to division (in our case through division artillery) and from there to army corps and army. We found out that any information we gave was considered to be worthless. We had been puzzled by the order that we take over in place from the 2nd Infantry Division. The explanation given us was that those in command did not want the Germans to know that we had relieved the veteran 2nd Division. But when we reported that German radio had broadcast to us on our arrival, welcoming us to the position, and identifying all of the units, our orders were not changed to authorize us to improve our positions. I found out how little our intelligence meant to the various headquarters when I reported the various incidents to the division artillery intelligence officer (S-2), a West Pointer. He told me that he had been reporting these actions to the Division S-2 who had reported them to the Corps S-2, but had been assured that this was merely a diversion put on by the Germans to fool us into thinking that they were making an attack through our positions. Our Division Artillery S-2 intelligence officer said, "This is the route that the Germans took through Belgium in 1870 and have taken in every war since. It's in their tactics manual, and it is a training exercise for all German officers. I've told them that, and they don't believe me. They are convinced that the attack is coming well to the north of us." DECEMBER 16John R. Schaffner Early in the morning, before dawn, at 0605, our position came under a barrage of German artillery fire. I was on guard at one of our outposts, and though I did not realize it at the time, I was probably better off there than with the rest of the battery. We had a 50-caliber machine gun in a dug-in position, so being somewhat protected, I got down in the lowest possible place and "crawled into my helmet." During the shelling, many rounds exploded real close and showered dirt and tree limbs about, but also there were quite a few duds that only smacked into the ground. Those were the "good" ones as far as I was concerned. After about thirty minutes, the shelling ceased, and before any of the enemy came into sight, I was summoned to return to the battery positions. Aspinwall states that from an inspection of the fragments, somebody determined that the enemy was using 88-, 105-, and 155-millimeter guns. Elliott GoldsteinAs soon as I was relieved by Lieutenant Colonel Kelly on the morning of the sixteenth, I took a crew out with an aiming circle to make shell reports. The purpose of a shell report is to make it possible to locate the enemy artillery. The only equipment necessary is an aiming circle. The procedure is to set up the aiming circle pointed along the line of flight of the shell, which is easily determined by an inspection of the site of the explosion. The size of the crater indicates the caliber of the gun, and the direction from which it came is clearly indicated by the shape of the crater. The crater will also indicate the angle of the trajectory. By taking readings on a number of craters, it is possible to map the location of each gun. While we were leisurely engaged in this activity, we heard sounds which sounded like firecrackers popping in the distance. We looked up and saw our first German enemies on a slope to the right front, about one hundred yards away, dressed in white overgarments with white hoods. The white garments blended fairly well into the snow. They were firing at us. No one was hit, and we were more indignant than frightened. We fired back, they left, and we returned to the battalion command post. The 589th Field Artillery Battalion had two air liaison airplanes (Piper Cubs) assigned to its Headquarters Battery. Their principal mission was to act as the eyes of the artillery, by flying reconnaissance missions, and by observing and adjusting the firing of the guns. Lieutenant Scott was one of the pilots. Each pilot flew with an observer, who carried out the missions of observation and fire adjustment while the pilot flew the plane. Lieutenant Graham Cassibry, a forward observer in A Battery, sometimes flew as an observer with Lieutenant Scott. Lieutenant Cassibry had received fifty hours of pilot training, but was not a licensed or qualified pilot. The planes arrived at St. Vith and occupied the air strip there previously occupied by the 2nd Division. Earl A. ScottI had been told that we were going into a quiet sector. I drove up to the battalion position to report in. The weather was foul, and I didn’t attempt an aerial reconnaissance. However, on this day, December 16, the quiet was broken by the sound of artillery shells fired at St. Vith and at the battalion’s position. The air strip, which was a mile from St. Vith, was not shelled. Since the weather was foul, the other flight officer and I prepared to ride a jeep to the battalion position. We never got there. Lieutenant Cassibry intercepted us with a message from the air officer for us to return to the airstrip. He needed a plane up for observation, and gave me the assignment and designated Lieutenant Cassibry to be my observer. We returned to the airstrip and took off in my Piper L-4 airplane. Flying towards the battalion position, at about fifteen hundred feet altitude, we received machine gun fire. We saw tracer bullets, and heard the zip, zip of bullets just a few feet in front of the plane. What to do? The evasive action I’d been taught at Fort Sill, the field artillery school, was to execute a diving turn, and come out over trees or bare ground, and then to hedgehop out of danger. Pilots with the 2nd Division Artillery had told us that this maneuver was useless, since the Germans were on to it. They didn’t tell us, however, what maneuver to use. I did some rather tricky flying at that point, and eventually got us out of danger. Neither of us was hit. Upon returning to the airstrip, we found that the rear section of the fuselage was riddled with bullet holes. What a birthday celebration! I turned twenty-six that day. John R. Schaffner* At about 0800 the battery positions again came under heavy artillery fire, and again no casualties were reported. At about 0900 communication was again established with Division and with the 422nd Infantry Regiment. However, the lines were soon shot out again by the enemy artillery, and after 1300 the battalion was for all practical purposes isolated from its supported regiment. Captain Alva R. Beans, the communications officer, and Lieutenant Hockstad, assistant communications officer, went forward to the infantry regimental command post after 0900, and while returning were fired upon, and Captain Beans was severely wounded. He was brought in and later evacuated. At 0915 a report was received of enemy patrols in Auw. Lieutenant Wright from C Battery went forward to a position commanding a view of Auw, and from there directed fire on the town until he was pinned down by small arms fire. C Battery was unable to bring guns to bear directly on Auw due to a high mask of trees between it and the target. About 1030 a patrol was sent out as additional security to man defensive positions along the road from Auw. Since it was now apparent that the enemy held Auw, an attack from that direction was expected. This patrol soon reported small arms fire from the enemy infantry moving out of Auw. An observation post was set up in the attic of the building of the house in which part of Headquarters Battery was quartered. At about 1500 three enemy tanks were seen coming along the road from Auw towards the battalion command post. At about four hundred yards range, the lead tank opened fire on one of our outposts, damaging three machine guns. Small arms fire was directed against the tank, but it just "buttoned up" and kept coming. When it came within range of our bazookas, they fired, and one hit and immobilized the lead tank. It was immediately hit again by an A Battery 105 howitzer and burst into flames. The enemy crew bailed out and were killed by small arms fire. The second and third tanks also took hits but were able to withdraw to defiladed positions. One of the tanks kept up harassing fire from a hull-down position, but counterfire was directed at it, and it is believed that it too was knocked out. The effective work of this patrol and our firing batteries kept the whole battalion position from being overrun that afternoon. John F. GatensSome of the published accounts of the defense of the gun position by a gun from A Battery are incorrect. I know because I was the gunner serving under Sergeant Shook in the section which was in the number one position. Although we were the number one Section, we may have been in that position by accident. On the way to the position, our truck broke down. The other three guns went on and we followed later. We entered the battalion area on a road going northeast to Auw, which passed through the middle of the battalion's position. A Battery’s position was on the right of the road, and the other batteries were on the left. When we arrived, the guns which preceded us had gone into position in the two, three, and four positions, leaving the one position open for us. Because of the snow it was difficult to get into position, and had they gone in in a different order, we would not have been able to go around them. The battery was in a defilade, the ground sloping away from the road. My gun was on the higher ground, the others being masked by the higher ground in front of them. The battery was firing indirect fire when three tanks appeared, approaching on the Auw-Bleialf Road. Our gun was the only piece that could reach the tanks, so we were the section to fire on them. We were ordered to cease firing the missions given the battery, and fire directly on the lead tank. In direct fire with a 105-millimeter howitzer, the gunner is in charge. He must sight the piece in the same way you aim a rifle but using a gunner's sight. The gunner's sight, which has vertical and horizontal crosshairs, and magnification, is mounted on the carriage to the left of the tube, and moves with the movement of the tube. Fortunately, we had trained on this, and I didn't hesitate. I aimed at the lead tank, by first setting the elevation to allow for my estimate of the distance to the tank, and then traversing the tube until I thought I had the howitzer aimed at the tank. I was looking through the sight and tracking the tank when four men came into view, racing toward us down the hill. I was afraid I might hit them if I fired at the tank, so my #1 cannoneer and I ran out in front of the gun, and by motioning with our arms that they should lie down, and yelling our brains out, we got the message to them. I was anxious that they lie down in place, instead of running toward us, since I didn't believe the tank had spotted us, and if they had continued towards us, they would have attracted attention to our position. As soon as I had a clear field of fire, I fired my first shot. The first round, fired on my command, missed the target. Sergeant Shook, who was standing behind me to observe through his binoculars, shouted, "It's a little high!" I lowered the elevation and gave the command to fire. It was a direct hit. We then fired another round for good measure. The tank blocked the road and prevented the other tanks from advancing. That was the first time the battalion engaged in direct fire--but it certainly wasn't the last. After we completed firing on the tanks, I scanned the area but couldn't find the other tanks. We were then given a new fire mission. The elevation we received was the one and only time we were ordered to raise the tube to its maximum elevation. The command for the powder charge was either one or two powder bags. With the howitzer in its maximum elevation and a small powder charge, the shell will fly relatively high but will land a relatively short distance from the firing position. I believe we were firing on the other two tanks. To my knowledge, there was no other direct fire by the battery in that position. I've often wondered, had the tanks not been stopped, whether we would have reached Baraque de Fraiture, or we would have been overrun and captured right there. Charles F. JacelonMy assignment was as forward observer sergeant in A Battery of the 589th. I served under Lieutenant Willard Crowley. Corporal Hugh Mayes was our radio operator and Private First Class Reed was the telephone man. We had a comfortable cabin for six. Two of the infantrymen shared our quarters. Our observation post was on the forward slope of a hill in a tree line a few hundred yards from our quarters. Lieutenants Crowley and Reed were on the observation post from 0800 until noon, and Mayes and I manned the observation post from noon until 1600. For the five days that we occupied that position we saw no movement. On December 15 we were relieved by another forward observer team. The plan was that the several forward observer teams would rotate around several different positions to familiarize all the officers and crews with our area of operations. Lieutenant Crowley's team was to spend the next period in the firing battery area with jeep servicing, laundry, baths, etc. We found unoccupied bunks in the hutments in the area and went to bed. Before dawn on December 16 the battery area came under enemy artillery fire, and several V-1 buzz bombs flew over. A Battery started firing on orders from the fire direction center. Prüm, Germany, was at the maximum range of our 105-millimeter howitzers. Since I had no assigned duties on the guns, I started carrying shells to the gun positions, which fired all day. At one point three German track vehicles came up the road from Auw. These vehicles must have been those that Major Goldstein and his bazooka teams engaged, although we had no knowledge of their actions. The gun in our left-hand position was called out of the fire mission in progress and fired point blank on the tracked vehicles on the road, several hundred yards ahead. At one point this gun had to stop firing to allow two American soldiers to enter the battery area from the front. Elliott GoldsteinI was assigned to coordinate the defense of the command post. We set up an outpost forward of the command post in a house where the communications group of Headquarters Battery was stationed. Soldiers with carbines from Headquarters Battery were deployed around the area of the outpost. Two bazooka teams reported to me and were deployed on either side of the road. I took command of the personnel in the area and instructed them not to fire on tanks except on my command. At about 1400 three tanks were seen coming over the ridge on the road from Auw that led into the battalion position. Captain Huxel, the Assistant S-3, had set up an observation post in the attic of the building near which our existing observation post was set up. He attempted to adjust fire on the tanks but was unable to see the lead tank because of trees in his line of sight. When the lead tank was about two hundred yards from the outpost, it fired on a machine gun on the right of the outpost, damaging its tripod. The tank approached another fifty yards, and the tank commander opened his hatch and traversed his gun towards the outpost and fired on it. I gave the order to open fire with small arms, and the tank commander buttoned up his hatch. The bazookas were then ordered to fire, and the gunner on the left side of the road hit the track of the lead tank. (Unfortunately, the gunner was then hit by a shell, probably from the tank.) A Battery then fired and immobilized the tank, which burst into flames. The crew and accompanying infantry dismounted and were fired upon by a machine gun. Since the bazookas were the principal defense of the battalion command post, I thought it was important that we recover the bazooka and the rounds which the gunner had with him. I decided to make a run for it, which meant crossing the road, and then running along a ridge to the bazooka position. I was fired on as I came to the ridge. I dove to the ground and managed to crawl into a truck rut. Fortunately for me the ground was very soft because of the snow and rain, and a prime mover which had driven across the ridge had made very deep ruts. I crawled into a deep rut on my stomach and, looking straight ahead, I saw the bazooka clutched in a bloody arm, all that was left of the man who had fired it. The sight shocked me, but I was even more disturbed when a round hit just short of the truck rut. I thought at the time it was a mortar shell, but I now believe it must have been a round from a tank. It was immediately followed by a round on the other side of the truck rut. I now knew that the German gunner had a bracket on me and that I could expect either one more adjusting round, or if the gunner thought the bracket small enough, he would lower his elevation by one half of the difference between the elevation of the over and the short, and would fire several rounds, assuming that one would hit the target (fire for effect). I accepted the fact that I was going to die, and as I stared at the bloody arm in front of me, I realized that there was nothing I could do except to pray and wait for my fate. As I expected, three shells exploded near me, all short. Fortunately, none of them scored a direct hit on the rut, and the ground was soft enough so that the explosions, although close, were absorbed in the ground. As soon as I was sure that the firing had ceased, I backed down the rut with the bazooka and one round and worked my way back to the battalion observation post. Meanwhile, Captain Huxel adjusted fire on the second tank and damaged it, and the third tank withdrew. Fire was continued on the road, adjusting the guns to form a rolling barrage. I next went with Captain Brown, commanding officer of B Battery, to assist men who had been wounded on the north of the road. While we were helping them, one of the tanks (I believe it was the third tank) took a hull-down position behind the ridge to the east and commenced firing on personnel occupying the outpost. After seeing the men on their way to an aid station, Arthur Brown and I worked our way back to the battalion area, went to the attic of the building in which the observation post was located and adjusted fire on the flash of the hull-down tank. We believe that we scored a hit, since the firing ceased. If we didn’t hit it, we may have convinced him that it would be safer to get out of the way. Randolph C. PiersonFor me, the morning of December 16 literally started with a bang. About 0600 I was outside the sturdy German farm house which the 589th Field Artillery Battalion was using as a command post, relieving myself in the frigid morning air at the outdoor latrine, preparatory to going on duty in the Fire Direction Center. The area north and east of us was unusually active. Squatting over the open slit trench of the latrine, with my pants around my knees, I was able to watch distant flashes of light on the horizon, and could hear the constant roll of artillery fire in the distance. This scene reminded me of early morning thunder and lightning activity I had witnessed many times during the summer months back home in central Florida. This interesting early morning scene was cut short by the "Whoosh--Whoosh--Whoosh" sound of an incoming artillery round. Instinctively I pulled up my pants and long johns and fell flat on the ground. The German artillery shell exploded nearby with earth-shaking power and sprayed my backsides with chunks of ice and frozen mud and filled my ears with the distinctive "Buzzzzz" of shell fragments passing above my prone body like a swarm of angry wild bees. Lying there, cold, frightened, wet and muddy, and my rear end still covered with feces, I received my introduction to the horrors of combat! Shortly after this experience, I was on duty in the Battalion Fire Direction Center, in the relative safety of the command post, where things had gotten chaotic. All the senior officers--Lieutenant Colonel Kelly, Major Goldstein, and Major Parker--were frantically trying to find out what was really going on. What is going on? What is the situation? No one seemed to be able to find out! The fire direction non-coms on duty, Technician Fifth Class John Celeric, Technician Fourth Class Delbert Miller, and I (Technician Fourth Class Randy Pierson), finally cornered the battalion intelligence sergeant, Technical Sergeant Frank Tacker, to get his evaluation of the situation. Frank told us he had two theories, (1) Jerry had accumulated some excess artillery ammunition and was just giving us hell in this sector, or (2) a major German attack would follow this mammoth artillery preparation. Of course, Technical Sergeant Tacker's second option turned out to be correct. History has recorded this attack as the beginning of the Battle of the Bulge. A short time later intelligence reports trickling in led us to believe that the positions of the 589th Field Artillery Battalion would be attacked by German tanks and infantry coming from the direction of Auw, Germany, which was located to the north of us. However, the battalion intelligence officer, Lieutenant Joe Cocke, was concerned with a large concentration of German troops known to be in the vicinity of Prüm, Germany. We had lost contact with the infantry, and the Fire Direction Center was almost useless. Consequently, I was detailed to establish a listening observation post on a small secondary road that ran east, in the direction of Prüm. Two Headquarters Battery men, Private First Class Brown and Private First Class Lemley, accompanied me to the location indicated on a map. "Brownie" was my radio operator, and Lemley came along to "ride shotgun" and take care of the Sarge. On the way we picked up a fourth member of the team, the battalion artillery mechanic, I remember as Corporal Fairchild. I was instructed to look, listen, and report what we saw and heard from this position quite a distance east of the command post. We were expected to encounter one of two conditions during this mission, (1) our own infantry withdrawing, or (2) advance elements of an enemy attack. We were to report what we saw and accompany our friendly infantry back to the command post, or report and withdraw if we encountered enemy activity. We encountered an enemy armored patrol. Against instructions, we fired a bazooka at the lead-tracked vehicle, a medium Panzer, a Panther I think, and the second bazooka round knocked off a track. The wounded Panzer effectively blocked the narrow road and the two or three following tracked vehicles immediately withdrew in the direction of Prüm. Private First Class Brown was unable to contact battalion by radio to report this patrol and action. Private First Class Lemley proved his valor and marksmanship by dispatching the Panzer crew with withering small arms fire as they tried to exit their wounded Panther. During our engagement with the Panzer, I was slightly wounded in the face, but the three things I remember most clearly after this short but violent action are: · The personal bravery of Private First Class Lemley; · The professional and calm manner in which Corporal Fairchild conducted himself in this stressful and dangerous situation; and · How afraid I was to actually fire the bazooka. I was a patient in the station hospital at Fort Jackson, SC, a victim of spinal meningitis, when the 589th received bazooka training. My thanks to Corporal Fairchild for giving me "on the job training" in use of the bazooka. I am still proud to have hit the damned Panzer twice, the only two times I have ever fired a bazooka in my life. Arthur C. BrownAll day long we fired salvo after salvo until our guns boiled. Our battery executive officer, Ted Kiendl, went out in front of the battery to survey the situation. He was assisting in bringing in our wounded. A German assault gun had the area in its sights and was chopping up the wounded and dead with solid shot for the shock effect. As Ted brought in a wounded soldier to a log lookout post, a round of German 88 hit the shelter, spraying his face and shoulder with pieces of log. I remember him coming back to the battery dugout shouting that "nothing could live out there." He was bleeding profusely, and the blood got all over some of the letters that we'd been censoring. Ted was badly wounded and had to be evacuated, fortunately before the Germans got behind us and cut off the escape routes. Elliott GoldsteinTed came up to the command post--I believe he was still walking, although bleeding profusely. He had carried a wounded soldier back to safety. Ted was a giant of a man who had played football at Yale when football players played both defense and offense, so he was physically and mentally strong. He was put on a stretcher to be evacuated. His last words, said to me with a smile, were "Coach, I'm turning in my jockstrap. They're playing too rough out there." (Fortunately, Ted survived and returned to duty with the outfit.) Arthur C. BrownHaving confiscated a German "burp" gun from my forward observer, Lieutenant Cassibry, I went forward to reconnoiter. The situation was very serious, enemy tanks followed by infantry were coming straight at our gun position down the road from Auw. The Germans were in behind our infantry, having infiltrated from the exposed left flank. Lieutenant Eric Wood had succeeded the command of A Battery as Captain Menke was captured in the first German assault. A Battery saved the day by knocking out and driving back the initial assault of enemy armor upon which they could "direct lay" the guns. Charles F. JacelonIn the late afternoon Major Goldstein called for a jeep for a reconnaissance mission, and I said that I was available. He said that we would go after dark. We started out down a bare slope towards battalion headquarters, which was in a farmhouse on the road. In the darkness I ran into some steel cable frozen into the ground. After ten minutes of my unsuccessful attempt to break free, Major Goldstein switched jeeps, and some time later a prime mover towed me out of the entangling cable. I proceeded down the hill and spent the rest of the night at battalion headquarters. Elliott GoldsteinWe had received orders to withdraw to a new position. I was given the map location of our new position and directed to take a party with me to reconnoiter the gun positions and lead the batteries into position when they arrived. The position was about four kilometers south of Schönberg and about the same distance (by road) southeast of our first gun positions. DECEMBER 17Calvin V. AbbottI was a wireman in A Battery, Captain Menke’s command. The first time that I remember meeting Major Goldstein was after we moved to the position south of our first position. He was in a house being used as a headquarters, and we were sent there. The house was dark; the windows were covered with blankets. Major Goldstein had a map on a table and a field telephone. He told me to go into the back room and guard two women and an old man. The woman tried to get me to come over and lie on a couch or something, but I wouldn’t do it. I sat in the chair with my carbine and watched them. The old man was facing me, chewing tobacco. He would spit on the floor in front of me, but he never reached me. The major also instructed me that there was a young girl upstairs and that no one should be allowed upstairs. No one went upstairs. After it got light, I went down to A Battery’s command post and operated a telephone for Lieutenant Wood, who was commanding the battery. There was a little shack in the immediate area, and Lieutenant Wood went into it and took a nap. I don’t remember the exact time, but shortly afterward a weapons carrier and jeep came down the road. The men in the jeep hollered that a German tank was right behind them, so you better come on and get in the jeep. I went in the shack and woke up Lieutenant Wood and told him to come on and get in the jeep. He came out, headed down the road and started giving a firing order. I told him the guns were pulling out, or trying to. He kept on giving a firing order. The men in the jeep kept hollering, “Come on. We are the last jeep. Come on!” I pulled him by the arm and told him to come on, the jeep was going to leave us, but he kept giving orders. I ran and got in the jeep as it was moving out. That was the last time I saw him, standing in the road and calling out orders. We were the last vehicle in a group moving down the road. John R. Schaffner*