|

477th

Bombardment Group |

|

|

The Men

and Their Airplanes: The Bombers Stanley Sandler on page 119

of his book, Segregated Skies: All-Black Combat Squadrons of WW II,

"The 477th Bombardment Group was conceived solely in response to

black pressure, rather than to any perception that black Americans in the

Army Air Forces could make any great contribution to the war effort. And

it remained a paper outfit from its activation in June 1943 until January

1944." [Author's note: Some

sources call the 477th Bombardment Group the 477th Bombardment Group

(Medium) and some sources list them as the 477th Bombardment Group

(Negro).] By late 1944 the 477th was

able to conduct combat training missions, but winter conditions reduced

flying time. When not fighting weather and equipment, the men also faced

racism from white officers and men. Promotions went mainly to the white

officers and enlisted staff while black promotions were limited. In March,

1945 the 477th was moved to Freeman Field, Indiana. Tension between white

and black personnel increased. Part of the problem of the 477th lay in its

white base commander, Colonel Robert Selway whose strict segregationist

policies hurt morale and led to the Freeman Field incident on April 5,

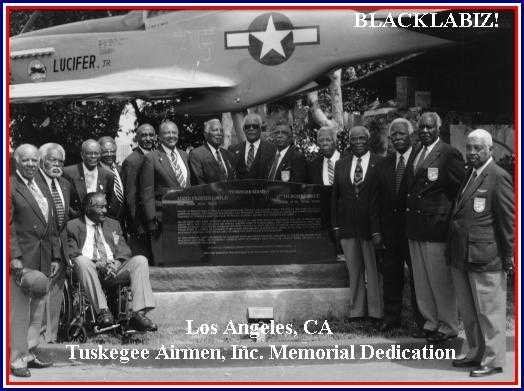

1944. The 477th's contribution

was not in its combat record. Ultimately the Freeman Field incident opened

the door to the eventual desegregation of the USAAF. As Sandler notes on

page 131, "The 477th, although lingering on as a unit until 1947,

never saw combat. It scored no "kills", blasted no enemy

positions, bombed no alien cities. But it had its victories. The 477th Bombardment Group

became the 477th Composite Group with B-25's and P-47's and trained for a

possible role in the Pacific Theater. The war ended, however, before the

477th could be deployed overseas in a combat role. The aircraft the 477th flew in training was the B-25 Mitchell medium bomber. This workhorse was used in both the European and Pacific Theaters. Variations of it included models with up to thirteen fifty caliber machine guns or a seventy-five (75 mm) cannon for anti-ship missions in the Pacific.

A

version of this information appeared in the Summer 1993 issue of the IHS's

popular history magazine In January 1945 the

American effort in World War II was reaching a climax. GIs in Europe had

turned back the last German offensive on the western front at the Battle

of the Bulge, and in the Pacific Theater United States troops were

recapturing the Philippines from the Japanese. While military operations

were reaching a fever pitch overseas, back home in Indiana activity was

winding down at a military installation that had awarded wings to

approximately four thousand airmen: Freeman Field, located near Seymour.

Although the U.S. War Department had placed the installation on an

inactive basis on Jan. 27, 1945, the air base would soon be a proving

ground in a different struggle, not against fascism on the battlefront,

but against racism on the home front. Denied access to the base's

officers club on account of their race, approximately sixty officers from

the all-black 477th Bombardment Group, which was receiving bomber training

at Freeman Field, were arrested on April 3, 1945, when they attempted to

enter what the Indianapolis Recorder referred to as a "swanky

and modern officers club set up by order of Colonel Robert R. Selway, Jr.,

commander of the outfit." After the dust had settled, three

officers--Roger C. Terry and Marsden A. Thompson, both of Los Angeles, and

Shirley R. Clinton of Camden, N.J.--faced a court-martial, and

approximately 100 men from the air group (including current Detroit Mayor

Coleman Young) were jailed at Godman Field in Kentucky. The calm atmosphere of a

small Civil Aeronautics Administration (CAA) emergency field, located

southwest of Seymour, changed following the Japanese attack on Pearl

Harbor, which plunged the United States into war. On May 6, 1942, the War

Department announced that the Seymour CAA field had been selected as a

site for an advanced aerial training center for bomber pilots, to be

designated as Seymour Army Airfield. The base, which was renamed Freeman

Army Airfield on March 3, 1943, in honor of the late Capt. Richard S.

Freeman of Winamac, Indiana, included more than 400 buildings and was

built at a cost of approximately $15 million. The 2,550-acre facility the

federal government created in Jackson County was "the epitome of

military airfield design," according to Louis Osterman in his 1986

history of the base. The installation had an immediate financial impact on

a community still reeling from the Great Depression. Officially activated on

Dec. 1, 1942, under the command of Col. Elmer T. Rundquist, the air base

welcomed its first group of soldiers just seven days later. The added

population proved to be a boon for area businesses. "The stores were

open on Saturday night then, and the sidewalks were packed from curb to

store with townspeople, the farmers of the area and their families, and

soldiers in their wool, khaki uniforms and jaunty overseas caps,"

Seymour resident Carolyn Mahon told Osterman. To help meet the soldiers'

recreational needs, the city had been planning, even before the first

troops reached the base, to open a United Service Organization (USO)

center. It organized a U. S. O Council and obtained the use of the former

Greeman Furniture Store. The club opened in December 1942 and was the

scene of a number of dances and other activities for soldiers. The club,

however, did not provide services to all military personnel stationed at

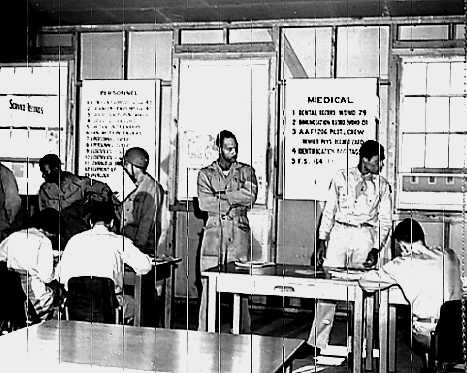

the air base. On Jan. 21, 1943 the first

members of the black 320th Aviation Squadron arrived at the Seymour

installation. The some 600 squadron members were used primarily as service

troops, performing such duties as cooking in the mess hall and tending the

base's 20-acre garden. Segregation in the armed

forces during World War II was widespread. In fact, it wasn't until

January 1941, after pressure from the National Association for the

Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and other groups, that the Army Air

Force (AAF) allowed blacks to become pilots. After being threatened with a

lawsuit, the War Department established an air unit (later known as the

99th Pursuit Squadron) for African-Americans near Tuskegee Institute,

Alabama. The Tuskegee Army Air Field, however, was completely segregated

at the outset, with fliers under the command of and trained by white

officers. Opportunities for blacks in

this state at the start of World War II were little better than those

offered by the Army. "It was nearly impossible to find in Indiana a

public place, institution, or group where whites accorded blacks an equal

and open reception," noted Indiana University Professor of History

James Madison in his history of the state from 1920 to 1945. Although

there were no actual statutes on the books, in many towns blacks

encountered so-called "Sundown laws," which forbade them to stay

in the city after dark In most aspects of their daily lives, from eating

in restaurants to watching motion pictures, African-American Hoosiers

faced discrimination and segregation. Jackson County was no

different from any other Indiana community in the 1940s "in that

segregating and insensitivity to civil rights issues were accepted facts

of life," noted Osterman. Because black troops stationed at the

airfield could not use the white USO club in Seymour, the USO Council

established a separate facility for them on West Tipton Street, which was

dedicated on Feb. 14, 1943, in ceremonies held inside the center because

of severe weather. Rev. John L. Prentice, Jackson County USO Council

chairman, formally presented the club to the city "as a channel of

service for the citizens." Segregation continued to be

a problem for the next black troops stationed at the Seymour base, the

477th Bombardment Group, which was part of the First Air Force. Under the

command of a white officer, Colonel Selway, a West Point graduate and Far

East veteran, the unit "had traveled a rocky road since its

activation in January 1944," according to then Colonel Benjamin O.

Davis, Jr. The first black graduate of the U.S. Military Academy in this

century and a member of the famed Tuskegee Airmen, Davis took charge of

the 477th during the height of the Freeman Field controversy. The first black squadron to

be trained for service in multi-engine airplanes, the 477th was originally

stationed at Selfridge Field, located near Detroit. The field had a

history of racial conflict. On Jan. 1, 1944, some black officers who had

attempted to enter the base's officers' club were blocked by commander

Colonel William L. Boyd and a second officer. This blockage flew in the

face of the armed force's own rules, specifically Army Regulation (AR)

210-10. According to that ruling, officers' clubs and other social

organizations were mandated to offer "all officers on duty at the

post the right to full membership, either permanent or temporary."

Alan Osur, who studied race relations in the AAF during World War II

found, however, that the military organization had "dogmatically

pursued a system of segregation that was almost impossible to maintain. It

even went so far as to violate War Department regulations in order to

prevent the mixing of whites and blacks in officers' clubs." Afraid that black

"agitators" in the Detroit area might incite trouble with the

Selfridge Field airmen (race riots had broken out in the city in June

1943), the AAF moved the 477th to Godman Field near Fort Knox, Kentucky.

At the new airfield, black officers were able to enjoy full use of the

officers' club. Racial relations, however, were not as promising as they

seemed. While blacks used the officers' club at Godman, their white

supervisors used the facilities at the segregated Fort Knox. Osur points

out that black airmen were powerless to protest the situation; since they

were not assigned to Fort Knox, they could not use its facilities. Other problems plagued the

black fliers at the Kentucky AAF base. Along with bad flying weather

during the winter, the field suffered from a lack of proper hangar and

apron space and an air-to-ground gunnery range. On March 1, 1945, the

477th moved from Godman to Indiana's Freeman Field. Trouble, however, soon

broke out between blacks and whites. The difficulties weren't with Seymour

residents, who, according to AAF Captain Earl D. Lyon in his study of the

bombardment group's war service, "were less openly antagonistic"

to black officers than residents of similar small towns located near Army

airfields. Instead, the racial trouble broke out on the base over a

familiar issue--the officers' club. In attempting to keep black

and white officers from using the same facilities, Colonel Selway, with

the support of AAF Major General Frank Hunter, took advantage of a

loophole in AR 210-10 by designating one officers' club at Freeman for

supervisory personnel and a second one for trainees, which resulted, as

Osur points out, in "de facto segregation." The issue came to a

head on the night of April 5, 1945, when 19 black officers, disregarding

an assistant provost marshal's orders to leave, entered the whites-only

club. Shortly afterwards, two other groups of blacks totaling 17 officers

joined the original group; all 36 were put under arrest by the provost

marshal. The next day, an additional 21 African-American officers were

arrested when they tried to enter the club. Freeman Field command,

through its public relations office, attempted to put its own spin on the

issue. It issued a statement to the Seymour Daily Tribune to the

effect that in the case of recreational facilities, it had "been a

long standing policy which applies throughout the United States which

maintains that it is unwise to have personnel in training utilizing the

same recreational facilities with those who train them." Even though

the two groups might use the same instructional facilities--classrooms,

training equipment, airplanes, ranges, etc.--after normal duty hours

"each . . . selects its own recreation and entertainment separately,

in order that they may relax from their official status." Despite the air base's best

efforts, the outcry over the incident would not die down. First Air Force

legal officers were soon on their way to Freeman Field to investigate the

matter. They found that Selway's original order was "inexact and

ambiguous as to its meaning or purpose," and all but three of the

black officers were released. (Lieutenants Clinton, Terry, and Thompson

were still under lock and key for allegedly pushing the provost marshal

when the entered the club.) A new directive from base commander Selway,

however, would spark more protests and lead to even more arrests. Selway, with General

Hunter's help, drafted an order for black officers to sign outlining what

facilities different personnel could use on the base. The directive also

included a place for the black officers' signatures indicating that they

had read and fully understood the order. Even when that designation was

stricken from the order, and the black officers were asked merely to

signify that they had read it, some continued to defy the authorities. A

total of 101 blacks--who became known as the 101 Club--refused to sign and

were flown back to Godman Field and placed under arrest awaiting

court-martial. Quentin P. Smith, who grew

up in East Chicago, Indiana, and learned to fly while living there, was

one of the 101 black officers arrested for not signing the order. An

Indiana State University graduate and former flying instructor at Tuskegee

Institute, Smith, due to his large size, had to transfer from fighter to

bomber duty. First Lieutenant Smith and the other black aviators did not

receive a warm welcome when they arrived at Freeman Field. Smith

remembered Colonel Selway informing the group that, along with the

officers' club, the base's tennis court and swimming pool were also off

limits to them. The announcement was not greeted favorably by the airmen:

"We booed the colonel loud and long," Smith said. The Hoosier native had a

more direct confrontation with the colonel after the officers' club

incident. Called into Selway's office and asked to sign the new directive,

Smith replied in a clear voice, "No, sir." Even when he was

threatened by the colonel with Article 64, which states that failure to

obey a superior officer's direct order could result in the death penalty,

Smith stood firm. In an oral history interview with Indiana Historical

Society Editor Doug Clanin, Smith remembered: "The immediate

major said, 'I order you to sign.' I didn't have any breath, I didn't have

any saliva left to say anything . . . I shook my head because I couldn't

even talk. So I said, 'no' [in high voice]. He rapped a gavel and said,

'you go out that door.' When I went out that door a soldier said, 'Go back

to your barracks, don't put your head out, don't come out, when suppertime

comes, we'll bring you your food.' So I'm sitting there by myself

thinking, 'now this just can't be true. I'm just about 190 miles from home

and this just can't be happening.' But it was. Organizations throughout

the United States, including the NAACP and black newspapers, swung into

action on the officers' behalf. The War Department received several

letters of concern from lawmakers, including Michigan Senator Arthur H.

Vandenberg, New York Congressman Adam Clayton Powell, and Indiana

Congressman Louis Ludlow. California Congresswoman Helen Gahagan (who

would be defeated for re-election after the war by Richard Nixon) even

telegraphed Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson urging that the officers be

released. These efforts paid off; in mid-April charges against the 101

black officers were dropped and the men were freed. Charges against the three

officers accused of pushing the provost marshal, however, remained in

effect. By the time the three came to trial, the 477th had a new

commander, Colonel Davis, former leader of the black 332d Fighter Group.

An all-black court-martial acquitted Thompson and Clinton of all charges,

convicting only Terry for "offering violence against a superior

officer." He was fined $150. The entire Freeman Field

situation deeply troubled Colonel Davis. Although he could understand the

underlying feelings of prejudice shown by officers from the Deep South, he

could not understand "putting the issue of segregated facilities

ahead of the need to prepare the group for war; nor the decisions to move

the 477th from one airfield to another, which halted progress toward

combat readiness for several months." The 477th never had the

opportunity to prove itself in combat, as the group was still at Godman

Field when the Japanese surrendered to the Allies on Aug. 14, 1945. Although Freeman Field was

once again put on an inactive basis shortly after the officers' club

fiasco, its role in America's war effort wasn't finished yet. In June 1945

the War Department selected the base to serve as a testing ground for

captured enemy aircraft. Once again airplanes filled the skies over

Seymour. Two years later, the War Assets Administration gave the facility

to Seymour, which used the base as a municipal airport. Despite its crucial role in

training aircrews for combat, perhaps Freeman's greatest contribution to

America's fight against fascism was the incident with the black officers,

which, as Osterman points out, "caught the attention of the military

and forced a re-thinking of its policy of segregation." |

|

Page

last revised 10/18/2020

Page

last revised 10/18/2020