|

Vietnam Army Deserters |

||||||||||||||||

|

(NA-3) CAMP ATTERBURY, Ind., Sept. 23 - FIRST OF MANY - Among the more than 100 Vietnam War era deserters that began processing Monday in President Fords week-old amnesty program, at Camp Atterbury, in south, central Indiana, Walter E. Kriner, 31, of Indianapolis and four others granted interviews. Kriner, with Thomas Oney, 25, of Dayton, Ohio (left) and David E, Thoman, 24, of Columbus, Ohio, were among deserters already in custody when the program was announced. About 400 deserters are expected through. |

||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

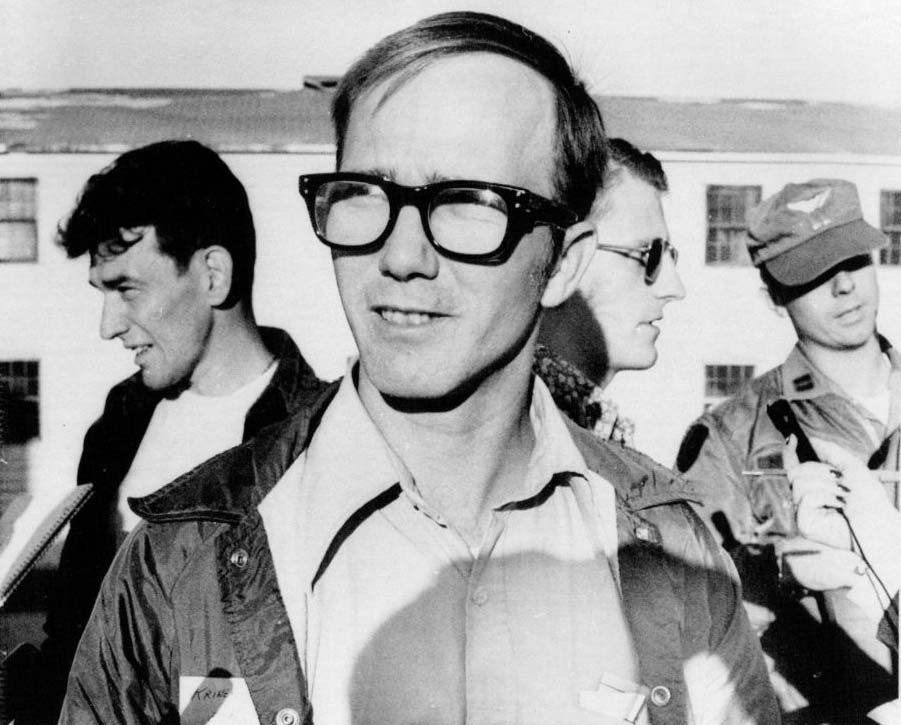

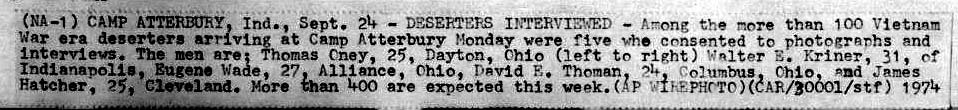

(NA-1) CAMP ATTERBURY, Ind., Sept. 24 - DESERTERS INTERVIEWED - Among the more than 100 Vietnam War era deserters arriving at Camp Atterbury Monday were five who consented to photographs and interviews. The men are : Thomas Clay, 25, Dayton, Ohio (left to right) Walter E. Kriner, 31, of Indianapolis, Eugene Wade, 27, Alliance, Ohio, David E. Thoman, 24, Columbus, Ohio, and James Hatcher, 25, Cleveland. More than 400 are expected this week. (AP WIREPHOTO) (CAR/30001/tf) 1974 |

||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

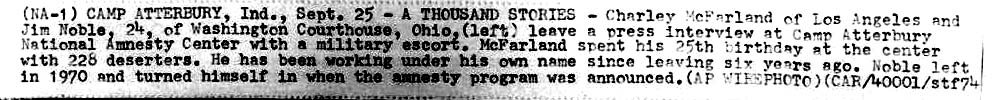

(NA-1) CAMP ATTERBURY, Ind., Sept. 25 - A THOUSAND STORIES - Charley McFarland of Los Angeles and Jim Noble, 24, of Washington Courthouse, Ohio, (left) leave a press interview at Camp Atterbury National Amnesty Center with a military escort. McFarland spent his 25th birthday at the center with 228 deserters. He has been working under his own name since leaving six years ago. Noble left in 1970 and turned himself in when the amnesty program was announced. (AP WIREPHOTO) (CAR/40001/stf7+) |

||||||||||||||||

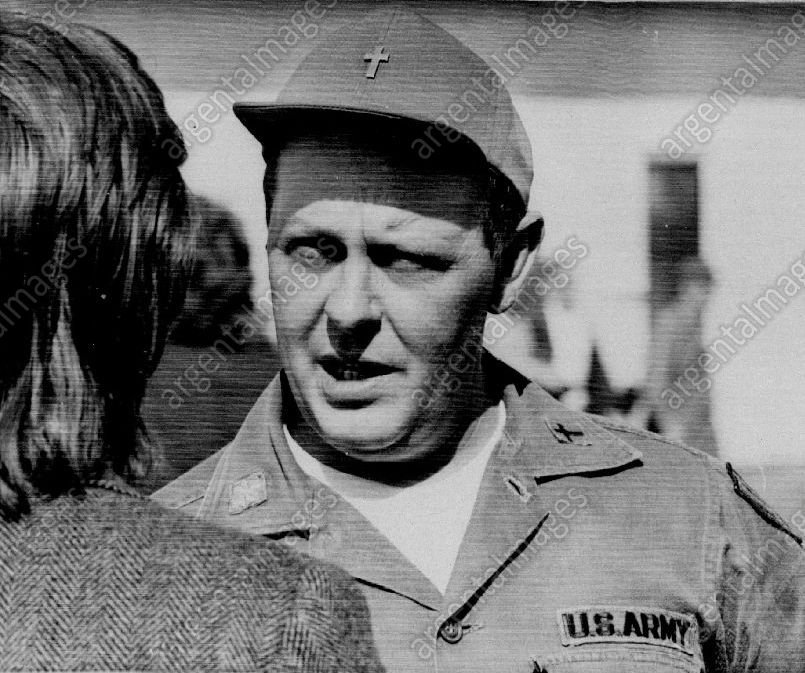

Army Chaplain Major Larry D. Scott at the Camp Atterbury National Amnesty Center said, "I haven't talked to a man yet who deserted for political reasons." The Chaplain is one of three at the center who have talked to more than 229 Army, Navy and Marine deserters being processed under President Ford's amnesty program. The center was opened Monday in weathered World War II barracks. 1974. AP Wire |

||||||||||||||||

|

The clemency program would cover offenses

that took place between the Senate ratification of the Gulf of Tonkin

resolution on Aug. 4, 1964, and the day the last United States combat

soldier left Vietnam, March 28, 1973.

Officials said that clemency would not be considered for deserters or evaders who faced other, unrelated charges. Draft evaders would be required to "execute an agreement" acknowledging allegiance to the United States and pledging to fulfill the period of alternative service. Deserters would be required to take an oath of allegiance to the United States, as well as agreeing to fulfill the term of alternative service. Officials estimated the cost of the program at about $2-million, most of this for processing and administrative details. The salaries for deserters or evaders would be paid by the employer. (New York Times, September 16, 1974) |

||||||||||||||||

ABC Evening News for

|

| Abstract: | (Studio) Ford to meet with

Defense Secretary James Schlesinger and Attorney General William Saxbe

with regard to amnesty. Army considers 2 Midwest bases to process

deserters. REPORTER: Harry Reasoner (DC) Army chooses Fort Benj.

Harrison and Camp

Atterbury,

both in IN, for their central location. 28,000 deserters on military

rolls. |

|---|---|

| Broadcast Type: | Evening News Segment Type: News Content |

| Header Link | 33045 |

| Record Number: | 33053 |

| Begin Time: | 05:10:40 pm |

| End Time: | 05:11:50 pm |

| Duration: | 01:10 |

| Reporters: | Reasoner, Harry; Tomlinson, Frank |

NBC Evening News for

Friday, Aug 30, 1974

Headline: Amnesty / Administration / Army

| Abstract: | (Studio) Ford to decide on extent

of leniency soon. Defense Secretary James Schlesinger and Attorney

General William Saxbe to present views to Ford Saturday Army

recommends 2 IN bases: Fort Benj. Harrison and

Camp

Atterbury where

returning deserters or evaders might be processed. Group demanding

total amnesty at White House REPORTER: John Chancellor (DC) Group claims petition for

total amnesty with 52,000 signatures. President assistant, Dr.

Theodore Marrs, meets group. [Gold star mother Mrs. Louise RANSOM -

says total amnesty won't dishonor her dead son.] [MARRS - says lost

father in World War I. No doubt Ford to search diligently for answer

with conscience.] No one in group felt Ford would grant total amnesty.

|

|---|---|

| Broadcast Type: | Evening News Segment Type: News Content |

| Header Link | 478586 |

| Record Number: | 478593 |

| Begin Time: | 05:35:20 pm |

| End Time: | 05:37:30 pm |

| Duration: | 02:10 |

| Reporters: | Chancellor, John; Cochran, John |

ABC Evening News for

Monday, Sep 02, 1974

Headline: Amnesty / Deserters' Camp

| Abstract: | (Studio) Ford to meet with

veteran's groups on conditional amnesty. Pentagon suggests IN Army

center for processing deserters. REPORTER: Howard K. Smith (Camp

Atterbury,

IN) Old facility only used now for summer training. Believed

camp could hold

5000 deserters. [Info. ofr. Major Tom KALLUNKI - is against appearance

of concentration camp.

Depends on how lenient program is to be.] Army has 8000 deserters. |

|---|---|

| Broadcast Type: | Evening News Segment Type: News Content |

| Header Link | 33347 |

| Record Number: | 33351 |

| Begin Time: | 05:05:20 pm |

| End Time: | 05:07:20 pm |

| Duration: | 02:00 |

| Reporters: | Miller, Ron; Smith, Howard K. |

CBS Evening News for

Tuesday, Sep 17, 1974

Headline: Amnesty Plan

| Abstract: | (Studio) Under terms of President

Ford's conditional amnesty plan, many men temporarily freed from jail

for serving time for draft dodging. Attorney General William Saxbe

orders prisoners' release; Defense Secretary James Schlesinger sets up

review system for 700 deserters in military prisons. Clemency board

expected to review convictions during furlough period. REPORTER: Roger Mudd (Lompoc, California) [Released

draft evader Gregg DAVIS - thinks his imprisonment uncalled for.]

[Christopher MUSSER - says he wanted to perform alternate service when

be was 1st drafted.] Questioned about his activities during days of

freedom. [MUSSER - plans to visit friends and relax.] (Studio) From evaders and

deserters still at large, very few respond to Ford's amnesty plan. (San Francisco, California) John

Barry was 1st to surrender. [Evader, BARRY - wants everything

straightened out between himself and government] [US attorney James

BROWNING - advises other resisters to follow Barry's action.] (Studio) Initial response to

clemency plan mainly in form of telephone inquiries. (DC) Calls from draft evaders are

all similar; details given. Very few of eligible deserters and evaders

have called special information ctrs. Deserters and evaders to be sent

to Camp

Atterbury, IN.

Film of camp

shown. |

|---|---|

| Broadcast Type: | Evening News Segment Type: News Content |

| Header Link | 236204 |

| Record Number: | 236205 |

| Begin Time: | 05:30:30 pm |

| End Time: | 05:35:40 pm |

| Duration: | 05:10 |

| Reporters: | Drinkwater, Terry; Meyer, John; Mudd, Roger; Threlkeld, Richard |

ABC Evening News for

Wednesday, Sep 18, 1974

Headline: Amnesty Plan

| Abstract: | (Studio) All imprisoned draft

evaders released yesterday pending review of cases by clemency board 1

prisoner refuses to leave jail without full pardon. Report follows

from military installation set up to receive draft deserters. REPORTER: Harry Reasoner (Fort Benjamin Harrison, IN) Very

few deserters call installation requesting clemency plan information

After January 31, 1975, information received from deserters now may be

used by Army to apprehend deserters if clemency plan not taken

advantage of during allowed period. Those deserters returning under

amnesty plan will be sent to

Camp

Atterbury, IN.

|

|---|---|

| Broadcast Type: | Evening News Segment Type: News Content |

| Header Link | 33300 |

| Record Number: | 33307 |

| Begin Time: | 05:07:40 pm |

| End Time: | 05:09:00 pm |

| Duration: | 01:20 |

| Reporters: | Miller, Ron; Reasoner, Harry |

ABC Evening News for

Thursday, Sep 26, 1974

Headline: Clemency Plan

| Abstract: | (Studio) Army has processed 132

deserters at Camp

Atterbury.

REPORTER: Harry Reasoner (Camp

Atterbury,

IN) Most deserters taking advantage of clemency plan already in prison

for desertion. [Arthur SENTER - says if alternative service suitable,

he'll take it, but if not, he may keep dishonorable discharge.]

[Eugene WADE - doesn't plan to take alternative service.] [John

McARDLE - explains reason for deserting Army.] [James HATCHER - says

petition to make rank refused, so he deserted.] Other deserters voice

reasons for desertion. |

|---|---|

| Broadcast Type: | Evening News Segment Type: News Content |

| Header Link | 33452 |

| Record Number: | 33463 |

| Begin Time: | 05:12:10 pm |

| End Time: | 05:14:20 pm |

| Duration: | 02:10 |

| Reporters: | Dobbs, Greg; Reasoner, Harry |

CBS Evening News for

Friday, Nov 29, 1974

Headline: Amnesty Program / Draft Deserter Profiled

| Abstract: | (Studio) President Ford grants

full pardons or conditional clemency to 18 former Vietnam draftees.

REPORTER: Walter Cronkite (White House) [President FORD -

says American won't forget those who served and died in Vietnam, but

in that same spirit, formal clemency underway.] Amnesty program

generally ignored. Clemency board chairperson Charles Goodell says

very few men eligible for amnesty program have come forward. (Studio) Only 118 draft dodgers

turn themselves in, but number considerably higher for draft

deserters. (La Jolla, California) Jim Dobbins

deserted Army in `69; discusses his decision to return to United

States from Canada. [DOBBINS - says decision very hard to make.] Plans

to clean up records in United States then resume life in Canada.

Dobbins processed at

Camp

Atterbury, IN; length of Dobbins alternative service depends

on several factors. By evening, Dobbins learns he'll serve 21 mos.

alternate service. Dobbins flies to San Francisco and visits draft

board; must find alternate service job within 30 days. Dobbins visits

ocean and family for 1st time in 6 years [DOBBINS - doesn't feel

extremely comfortable yet,although it feels good to be on familiar

ground.] After processing and orientation back in Army, Dobbins

decides to do alternative service and to stay in US. |

|---|---|

| Broadcast Type: | Evening News Segment Type: News Content |

| Header Link | 232142 |

| Record Number: | 232155 |

| Begin Time: | 05:41:10 pm |

| End Time: | 05:47:20 pm |

| Duration: | 06:10 |

| Reporters: | Cronkite, Walter; Schieffer, Bob; Young, Steve |

ABC Evening News for

Monday, Mar 31, 1975

Headline: President' Amnesty Plan / In Perspective

| Abstract: | (Studio) At midnight, President'

amnesty program for Vietnam era war deserters and resisters expires.

REPORTER: Harry Reasoner (DC) [On March 29, 1973, President

NIXON - urges American not to dishonor Vietnam war vets by granting

amnesty to those who deserted American] [On August 19, 1974, President

FORD - believes amnesty justified to give young men 2nd chance.] On

September 16, amnesty proclamation signed to help bind up American's

wounds. Film of Camp

Atterbury,

IN, shown. Majority of those eligible for clemency reject or ignore

President' offer. Telephone numbers of clemency board shown on

television screen. |

|---|---|

| Broadcast Type: | Evening News Segment Type: News Content |

| Header Link | 36489 |

| Record Number: | 36503 |

| Begin Time: | 05:22:50 pm |

| End Time: | 05:25:50 pm |

| Duration: | 03:00 |

| Reporters: | Reasoner, Harry; Reynolds, Frank |

What Happened to

Vietnam Era War Resisters?

War Resistance, Amnesty and Exile - Just

the Facts

by Harold Jordan

As the Vietnam War fades into the past, the struggle for reinterpretation continues. One area that has received insufficient attention is war resistance. The script offered in public circles often reads like this: the war has ended for resisters; isolated numbers of people resisted military service, most of them "draft dodgers"; all of the legal issues surrounding military resisters were resolved - they eventually "got off"; and people only refuse military service when they face a draft.

These myths, like most others about the war, are designed to influence future generations of potential warriors. The reality of the Vietnam Era is that large numbers of people resisted military service in different ways. Some were facing the draft while others resisted after enlisting in the military. Universal amnesty was never granted to war resisters. Here are the facts:

War Resisters and the Courts

Draft Law Violators - During the entire Vietnam War, 209,517 young men were formally accused of violating draft laws. Government officials estimate that another 360,000 were never formally accused. Of the former group, 25,000 indictments were handed down; 8,750 were convicted; and just under 4,000 served jail time.

Military Resisters - It is difficult to say how many military service members were prosecuted for offenses growing out of opposition to the Southeast Asia War. Most estimates consider the rates at which service members went AWOL (absent without leave) or deserted – commonly referred to as "absence offenses." AWOL and desertion rates hit an all-time high during the Vietnam War, 1971 and 1972 being the peak years. The Pentagon documents 1,500,000 instances of AWOL and desertion during the war. Official estimates of the actual number of service members who went AWOL or deserted run between 500,000 (Pentagon) and 550,000 (officials in the Ford Administration). It is important to remember that not all service members who received bad discharges for offenses related to the war were absentees. Adding other types of anti-war activities for which service members were prosecuted significantly increases these figures. Many went to jail and/or received bad discharges.*

Resisters in Exile

Estimates of the number of draft and military resisters who went into exile during the Vietnam Era vary widely. The best estimate is about 100,000, at least 90% of whom went to Canada. How many are still living abroad is unknown. The New York Times estimates that 25,000 draft resisters still live in Canada, an estimate which seems high by most accounts. (This figure does not include active duty service members who went into exile.) There are no reliable estimates: it is most likely still in the thousands.

Today military resisters who return to the United States may still face the possibility of punishment in the form of criminal prosecution or a bad discharge. GI resisters, including those living in exile, remain in legal jeopardy. No universal amnesty was ever granted them. The two 1970s limited relief programs expired decades ago. Every year a small number are arrested upon returning to the US. For example, Richard Allen Shields, who went AWOL from an Army base in Alaska in 1972, was arrested March 22, 2000 on the US-Canadian border (in Metaline Falls, WA) by U.S. Customs agents as he was attempting to drive a lumber truck across the border. Shields was taken to Fort Sill, Oklahoma and discharged from the Army with an "Other Than Honorable" discharge in April of 2000.

Relief for War Resisters

Two programs providing limited legal relief for draft and military resisters were implemented in the 1970s. Military resisters and draft evaders were treated differently from each other in both Ford and Carter programs.

Ford Clemency Program (1974)

In 1974, President Ford established a program of partial relief for war resisters. This clemency program was considered a complement to President Ford's pardon of President Nixon, who had resigned from office in lieu of likely removal by Congress. The program covered the following categories of persons: convicted draft violators, convicted military deserters and AWOLs, draft violators who had never been tried, and veterans with less than honorable discharges for absence offenses.

The Ford program was widely regarded as a failure, even by people who administered it. The conditions under which a person could receive relief were onerous and discriminatory. Persons receiving clemency were required to do up to 24 months of alternative service and were required sign broad oath of allegiance to the United States.

In addition to these measures, military deserters automatically received bad discharges ("Undesirable"), although they could later apply to get them changed to "Clemency Discharges" (considered "Other Than Honorable") after performing 24 months of service. Under the plan, GI participants would automatically lose all veterans benefits, unlike many other veterans with less than honorable discharges.

The program was widely regarded as a failure, even by people who administered it. Only 27,000 of the 350,000 eligible persons applied; 21,800 were granted clemency, mostly men living in the U.S., not exiles. Those granted clemency were almost equally divided between "draft offenders" and "military offenders." Most exile groups based in Canada, Sweden, Britain and France endorsed a boycott of the Ford program because of its punitive nature. The "oath of allegiance" requirement was considered especially offensive given the generous treatment of Nixon. Nixon received a pardon, pension, and was not required to swear allegiance to the U.S. despite his role in undermining democracy. Program administrators estimated that about 566,000 military "offenders" were still in need of relief after the Ford program ended, an ultimate indicator of the program's failure.

Carter Program (1977)

In 1977, President Carter established two programs to assist war resisters. In January of 1977 he declared an unconditional amnesty for draft resisters, both accused and those who could face possible prosecution. Later that year, he set up the two stage "pardon" process for military absentees.

Once again, draft evaders and military absentees were treated differently.

Draft evaders were granted unconditional amnesty automatically if there were no other legal charges pending. They would not have a criminal record. Young men who were Unfortunately, universal and unconditional amnesty was never granted to military resisters.considered draft evaders did not have to apply (in any formal sense) to get amnesty. It was a blanket amnesty granted to all draft evaders whether they had been engaged in a legal process or not. This is why no figure exists for the real number of draft evaders who benefited from the Carter program. This includes people who were never prosecuted, people who were investigated and not prosecuted, people who were indicted, people for whom charges had been brought, etc. The only restriction is that the person not have other (non-draft evasion) charges pending against them. So a draft evader who had criminal charges pending for participating in a protest would not have those protest-related charges dropped, only the draft evasion charges.

Similarly, military deserters and AWOLs could apply for a limited pardon if there were no other charges pending. Under the Carter program deserters would automatically receive a less than honorable discharge ("Undesirable"), but could apply for an upgrade later. The upgrade would not be automatic and few veterans received them. They were barred from receiving veterans benefits, unlike many other vets with less than honorable discharges. Military resisters had to apply for relief within a certain time frame, about 5-6 months, during 1977. Only 4,200 of them were considered eligible for the program; less than 25% of them were processed and received the less-than-honorable discharge. The program allowed for a case-by-case review of potentially another 430,000 cases of veterans with bad discharges; yet only 16,277 benefited from this procedure.

The Carter program was more successful than the Ford program despite its serious limitations. Many of the resisters (especially military absentees) had trouble surviving in other countries. Exile groups urged people to take advantage of the Carter program and work from within the US for a full amnesty.

One factor leading resisters to remain in exile was the poor advertising of the details of the Carter relief program (1977) in the aftermath of what was regarded as a highly discriminatory and defective Ford Clemency program (1974). Congress refused to fund the Carter program fully. Both relief programs had conditions many exiles found hard to accept. Finally, the period of time under which one could apply for relief was sharply limited.

Unfortunately, universal and unconditional amnesty was never granted to military resisters. It is estimated that only 28,420 Vietnam Era military resisters received any form of legal relief – many of them received bad discharges – while another 550,000 never received any form of relief. To place this figure in perspective, the number of ex-GIs who never received legal relief roughly equals the number of soldiers who participated in the Gulf War of 1990 and 1991. This is another way in which our country has yet to fully come to terms with the legacy of the war in Southeast Asia.

Sources

Leonard Baskir and William Strauss, Chance and Circumstance: the Draft, the War and the Vietnam Generation, New York: Random House, 1978.

New York Times (3/5/00)

Seattle Post-Intelligencer (4/10/00)

David Surrey. Choice of Conscience: Vietnam Era Military and Draft Resisters in Canada, New York: Praeger, 1982

About the Author

Harold Jordan founded American Friends Service Committee's National Youth and Militarism Program and acted as its Coordinator from 1986 - 2002. Currently, he is the Executive Director of the National Coalition of Education Activists. He can be reached at hjordan@edactivists.org. The author wishes to thank Jack Colhoun for his insightful comments.

* The term "bad discharges" refers to several categories of discharge from the military (such as "Undesirable," "Other Than Honorable," etc.) that may result in post-service job discrimination, the loss of veteran's benefits, or both.

http://www.afsc.org/youthmil/conscientious-objection/Vietnam-war-resisters.htm

Deserters Come in Slowly for Their Medicine

"There's a lesson to be learned from these people," says General Forrester. "Inevitably, these boys [deserted] because of poor leadership. They had problems, maybe with their wives or families, and when the military couldn't respond fast enough, they took off."

Thus far, Camp Atterbury has processed more than 1,100 deserters—admittedly, only about 10 percent of the total. Forrester and the Pentagon had expected many more, and had purposely set up the processing center away from a regular army base to avoid any friction between the deserters and regular soldiers. To staff the camp, Forrester hand-picked a cadre of 450 men, most trained in race relations and psychology. There have been no incidents, but because the flow of deserters has slowed to a trickle, the processing center is being shifted to Fort Benjamin Harrison. There, as at Atterbury, each returning deserter is interviewed and his explanation of why he fled included in a tan file folder along with the military's record of his service. Each case is then presented to the Joint Alternate Service Board—the men call it "Jazbo"—which recommends a term of alternative service of up to 24 months. (The Presidential Clemency Board in Washington rules on convicted draft evaders.)

"I expected to see stereotypes," the general says, "men who harbored real political hatred. But I realized the first day the reservoir of tragedy in each of these young men—in their faces, their bearing, even their dress. They had run, changed jobs, lied—they had to. I think they are glad to get it off their backs."

Forrester, a 26-year career soldier, was a West Point classmate of Alexander Haig and current academy commandant Sid Berry (PEOPLE, Sept. 2, 1974). A veteran of Korea and the Dominican Republic, he served two tours in Vietnam, where he was a brigade commander and later assistant division commander of the 1st Air Cavalry. Married to the widow of a fellow officer who was killed in a helicopter crash (Forrester's own wife was also killed in an air accident), they have six children, three from each marriage. "I have a 19-year-old son, Chip," says Forrester, "and he and I have had extremely volatile dialogue over the war in Vietnam. He isn't a militarist in any sense of the word." The general looks out the window at a newly arrived batch of deserters. "In fact," he says, "I'm not sure that under other circumstances something like this couldn't have happened to him."

Russell Wilson, 20, from Albany, Ga., joined the army in 1971 when he was 17. Six months later he deserted. "I just didn't feel it was right to kill someone," he says now. Assignment to Vietnam was "being sent to a place to shoot a guy who could never threaten you, to some weird place to fight and die." He kept on the run, never staying in one place longer than a couple of months, though he did manage to obtain security clearance for a job at a nuclear power plant in Maryland. Now a teamster, Wilson married a 23-year-old divorcée last year. This August he was stopped for a traffic violation in Michigan while taking one of his two stepchildren to the hospital, and was recognized as a deserter. Wilson was ordered to perform 24 months alternative service.

Harold Cummings, 27, is a machinist from the Baltimore ghetto. He had already honorably completed one tour with the army and decided to join the marines in 1972 because he "wanted something different." But when his mother became ill, he says, the marines wouldn't give him leave and he deserted. He was arrested earlier this year, and when the amnesty program began he was in the brig at Camp Lejeune, N.C. "People should realize we've been through enough," says the natty Cummings. "Most of us are tired of running." Nonetheless, the "ghost board" specified that Cummings devote the full 24 months to alternative service.

Phillip Rogers, 22, of Freer, Texas, near Laredo, wore a Stetson and boots to Atterbury. A skinny (6'2", 160-pound) oil field roughneck, Rogers had been in the army more than two years when he deserted in 1971. He was an infantryman in Vietnam, and when his mother took sick Rogers went home to Freer and stayed there. "Everybody knew I was AWOL," he says. "They figured I had a good reason; I'd served two years of good time and my Momma was sick and I needed to help support the family." He says he filed income tax returns every year but was not arrested. "I figured if they had wanted me, they'd have come and got me." He turned himself in and received 11 months of alternative service.

Michael Tooman, 25, from Pontiac, Mich., enlisted in the army in 1969 after he was drafted so he could train as a mechanic. But opposed to the war and worried about family problems, he deserted. He dodged the law for five years, finally settling in Seattle as a mechanic and carpenter. He is married, with a baby due in two months. When the amnesty program was announced he surrendered—and was so upset he couldn't eat for two days. What he really wants to do, he says, is stay in Washington state and start a buffalo herd. He has been told to do 22 months of alternative service.

Anthony Zambas, 24, from Aberdeen, Wash., joined the army in 1970. After basic training and 15 days of artillery instruction at Fort Sill, Okla., he deserted. "I wasn't threatened by the Vietnamese," he says. "Besides, I figured this war was a big moneymaker for some people—but not for me." He returned to Aberdeen and lived with his mother (who lost her first husband in World War II). "If I had gotten orders to Vietnam," Zambas says, "she would have lied and killed to keep me home." He stayed there until Ford's amnesty program was announced, then turned himself in. Zambas compliments the military on the "decency and mercy" with which he and the other deserters have been treated, but he adds, "Society ain't doing us no big favor; they got the word—we were sent by Jerry." Zambas was ordered to do 24 months alternative service.

ABC Evening News for Monday, Sep 02, 1974

Headline: Amnesty / Deserters' Camp

| Abstract: |

(Studio) Ford to meet with veteran's

groups on conditional

amnesty. Pentagon suggests IN Army

center for processing deserters. (Camp

Atterbury, IN) Old facility only

used now for summer training. Believed

camp could hold 5000 deserters.

|

|---|---|

| Broadcast Type: | Evening News Segment Type: News Content |

| Program Time: | 05:05:20 pm - 05:07:20 pm. Duration: 02:00 |

| Record Number: | 33351 |

| Link to this page | http://tvnews.vanderbilt.edu/program.pl?ID=33351 |

| Context |

|

| Reporters: | Miller, Ron; Smith, Howard K. |

ABC Evening News for Monday, Mar 31, 1975

Headline: President' Amnesty Plan / In Perspective

| Abstract: |

(Studio) At midnight, President'

amnesty program for Vietnam era war

deserters and resisters expires. (DC) [On March 29, 1973, President

NIXON - urges American not to dishonor Vietnam war vets by

granting

amnesty to those who deserted

American] [On August 19, 1974, President FORD - believes

amnesty justified to give young men

2nd chance.] On September 16,

amnesty proclamation signed to help

bind up American's wounds. Film of

Camp

Atterbury, IN, shown. Majority of

those eligible for clemency reject or ignore President' offer.

Telephone numbers of clemency board shown on television screen.

|

|---|---|

| Broadcast Type: | Evening News Segment Type: News Content |

| Program Time: | 05:22:50 pm - 05:25:50 pm. Duration: 03:00 |

| Record Number: | 36503 |

| Link to this page | http://tvnews.vanderbilt.edu/program.pl?ID=36503 |

| Context |

|

| Reporters: | Reasoner, Harry; Reynolds, Frank |

ABC Evening News for Friday, Aug 30, 1974

Headline: Amnesty / Plans

| Abstract: |

(Studio) Ford to meet with Defense

Secretary James Schlesinger and Attorney General William Saxbe

with regard to

amnesty. Army considers 2 Midwest

bases to process deserters. (DC) Army chooses Fort Benj. Harrison

and

Camp

Atterbury, both in IN, for their

central location. 28,000 deserters on military rolls. |

|---|---|

| Broadcast Type: | Evening News Segment Type: News Content |

| Program Time: | 05:10:40 pm - 05:11:50 pm. Duration: 01:10 |

| Record Number: | 33053 |

| Link to this page | http://tvnews.vanderbilt.edu/program.pl?ID=33053 |

| Context |

|

| Reporters: | Reasoner, Harry; Tomlinson, Frank |

NBC Evening News for Friday, Aug 30, 1974

Headline: Amnesty / Administration / Army

| Abstract: |

(Studio) Ford to decide on extent of

leniency soon. Defense Secretary James Schlesinger and Attorney

General William Saxbe to present views to Ford Saturday Army

recommends 2 IN bases: Fort Benj. Harrison and

Camp

Atterbury where returning deserters

or evaders might be processed. Group demanding total

amnesty at White House (DC) Group claims petition for total

amnesty with 52,000 signatures.

President assistant, Dr. Theodore Marrs, meets group. [Gold star

mother Mrs. Louise RANSOM - says total

amnesty won't dishonor her dead

son.] [MARRS - says lost father in World War I. No doubt Ford to

search diligently for answer with conscience.] No one in group

felt Ford would grant total

amnesty. |

|---|---|

| Broadcast Type: | Evening News Segment Type: News Content |

| Program Time: | 05:35:20 pm - 05:37:30 pm. Duration: 02:10 |

| Record Number: | 478593 |

| Link to this page | http://tvnews.vanderbilt.edu/program.pl?ID=478593 |

| Context |

|

| Reporters: | Chancellor, John; Cochran, John |

ABC Evening News for Wednesday, Sep 18, 1974

Headline: Amnesty Plan

| Abstract: |

(Studio) All imprisoned draft evaders

released yesterday pending review of cases by clemency board 1

prisoner refuses to leave jail without full pardon. Report

follows from military installation set up to receive draft

deserters. (Fort Benjamin Harrison, IN) Very few

deserters call installation requesting clemency plan information

After January 31, 1975, information received from deserters now

may be used by Army to apprehend deserters if clemency plan not

taken advantage of during allowed period. Those deserters

returning under

amnesty plan will be sent to

Camp

Atterbury, IN. |

|---|---|

| Broadcast Type: | Evening News Segment Type: News Content |

| Program Time: | 05:07:40 pm - 05:09:00 pm. Duration: 01:20 |

| Record Number: | 33307 |

| Link to this page | http://tvnews.vanderbilt.edu/program.pl?ID=33307 |

| Context |

|

| Reporters: | Miller, Ron; Reasoner, Harry |

CBS Evening News for Tuesday, Sep 17, 1974

Headline: Amnesty Plan

| Abstract: |

(Studio) Under terms of President

Ford's conditional

amnesty plan, many men temporarily

freed from jail for serving time for draft dodging. Attorney

General William Saxbe orders prisoners' release; Defense

Secretary James Schlesinger sets up review system for 700

deserters in military prisons. Clemency bd expected to review

convictions during furlough period. (Lompoc, California) [Released draft evader

Gregg DAVIS - thinks his imprisonment uncalled for.]

[Christopher MUSSER - says he wanted to perform alternate

service when be was 1st drafted.] Questioned about his

activities during days of freedom. [MUSSER - plans to visit

friends and relax.] (Studio) From evaders and deserters

still at large, very few respond to Ford's

amnesty plan. (San Francisco, California) John Barry was

1st to surrender. [Evader, BARRY - wants everything straightened

out between himself and government] [US attorney James BROWNING

- advises other resisters to follow Barry's action.] (Studio) Initial response to clemency plan

mainly in form of telephone inquiries. (DC) Calls from draft evaders are all

similar; details given. Very few of eligible deserters and

evaders have called special information ctrs. Deserters and

evaders to be sent to

Camp

Atterbury, IN. Film of

camp shown. |

|---|---|

| Broadcast Type: | Evening News Segment Type: News Content |

| Program Time: | 05:30:30 pm - 05:35:40 pm. Duration: 05:10 |

| Record Number: | 236205 |

| Link to this page | http://tvnews.vanderbilt.edu/program.pl?ID=236205 |

| Context |

|

| Reporters: | Drinkwater, Terry; Meyer, John; Mudd, Roger; Threlkeld, Richard |

CBS Evening News for Friday, Nov 29, 1974

Headline: Amnesty Program / Draft Deserter Profiled

| Abstract: |

(Studio) President Ford grants full pardons

or conditional clemency to 18 former Vietnam draftees. (White House) [President FORD - says

American won't forget those who served and died in Vietnam, but

in that same spirit, formal clemency underway.]

Amnesty program generally ignored.

Clemency board chairperson Charles Goodell says very few men

eligible for

amnesty program have come forward.

(Studio) Only 118 draft dodgers turn

themselves in, but number considerably higher for draft

deserters. (La Jolla, California) Jim Dobbins

deserted Army in `69; discusses his decision to return to United

States from Canada. [DOBBINS - says decision very hard to make.]

Plans to clean up records in United States then resume life in

Canada. Dobbins processed at

Camp

Atterbury, IN; length of Dobbins

alternative service depends on several factors. By evening,

Dobbins learns he'll serve 21 mos. alternate service. Dobbins

flies to San Francisco and visits draft board; must find

alternate service job within 30 days. Dobbins visits ocean and

family for 1st time in 6 years [DOBBINS - doesn't feel extremely

comfortable yet,although it feels good to be on familiar

ground.] After processing and orientation back in Army, Dobbins

decides to do alternative service and to stay in US. |

|---|---|

| Broadcast Type: | Evening News Segment Type: News Content |

| Program Time: | 05:41:10 pm - 05:47:20 pm. Duration: 06:10 |

| Record Number: | 232155 |

| Link to this page | http://tvnews.vanderbilt.edu/program.pl?ID=232155 |

| Context |

|

| Reporters: | Cronkite, Walter; Schieffer, Bob; Young, Steve |

ROBERT K. MUSIL

President Ford’s re-entry program for Vietnamese War resisters is part of a continuing cover-up of the terrible

costs and consequences of this nation’s intervention in

Indochina. It is designed to discredit resistance to the

war and, along with the Presidential pardon of Nixon,

bring to an and our long “nightmare” of bickering over

Indochina.

Mr. Ford’s August 19th speech announcing leniency

at the VFW Convention in Chicago came as a surprise

to many and was widely reported as a courageous step.

It was neither. With substantial numbers of the Nixon entourage in jail or awaiting

trial, leniency was on

the way in; law and order on the way out. Melvin Laird

and Robert Froehlke had run up trial balloons for conditional amnesty and the weather was fine—a little flak

from the VFW, but otherwise just fine. Meanwhile, in the wake of

Watergate, sentiment for amnesty was growing. In March, a majority of Americans favored conditional

amnesty.

Robert Musil, a former Army captain who refused to serve

in Vietnam, is associate secretary of the Central Committee

for Conscientious Objectors and a member of the steering

committee of the National Council for Universal and Un-

conditional Amnesty. He testified at the House Judiciary

subcommittee hearings.

International amnesty, and more than a

third were for unconditional amnesty. And at the House Judiciary hearings

on amnesty, it became clear that at least a conditional

amnesty might soon be in the works in Congress. [See

Musil: “Amnesty—What Kind and When?” The Nation, April 20.

Mr. Ford’s speech to the VFW is a classic example of

the kind of cynical manipulation that we have come to

expect of Presidential speeches. “Unlike my last two

predecessors, I did not enter this office facing the terrible

decisions of a foreign war.” This from a man whose first

complaint against Defense Secretary Schlesinger was that

he wasn’t effective enough at peddling aid to Indochina

to the Congress, and who was heard emerging from his first National

Security Council meeting as President singing the praises of a Congressman who stands “firm and

tail on the war.”

The speech was vintage Nixon “peace with honor,”

rewritten into Jerry Ford’s “straight talk.” It contains

the same self-serving analogies to Lincoln and Truman, the same

ritualistic invocation of Medal of Honor recipients, the same vilification of war resisters, those “few

citizens” who committed the “supreme folly of shirking

their duty at the expense of others.” But the worst was

yet to come. First came the “full, absolute and unconditional” pardon of Richard Nixon, and then in sharp

contrast, on September 16, the detailed White House announcement of the reentry plan.

As Atty. Gen. William Saxbe said earlier, persons

returning under the plan would have to show “contrition.”

So much, in fact, that the program looks as if it were

designed to fail. It provides for clemency for persons

convicted, charged, under investigation, or sought for

violations for portions of the Selective Service Act or

Articles of (desertion), 86 (AWOL), or 87 (missing

movement) of the Uniform Code of Military Justice

(UCMJ). Those not yet convicted of an offense must

turn themselves in by January 31, 1975, reaffirm their

allegiance to the United States, and agree to perform

two years of alternate service in the national interest.

Draft violators report directly to the U.S. Attorneys and will be relieved

of prosecution upon completion of alternate service. Military absentees

return to a central processing point, first located at Camp Atterbury,

Ind., and now

at Fort Benjamin Harrison, sign their oath, agree to do

alternate service and, then receive an undesirable discharge (UD). If and when they complete alternate service

they receive a new clemency discharge.

Those already convicted of offenses eligible for amnesty

apply to a nine-member Presidential Clemency Board

which reviews theft case and may recommend clemency

to the President contingent on up to two years of alternate service. Draft violators may have theft civil rights

restored, but their records will not be expunged. Veterans

holding undesirable or punitive discharges for desertion offenses will

receive a clemency discharge upon completion of alternate service. That is a simple explanation

of the program, and even on its face, it is insulting and

unacceptable to most war resisters. On closer examination, the plan is even worse—conceived in bad faith and

riddled with traps, inconsistencies, illegalities and inequities.

To begin, the plan does not even cover

most war

resisters. According to official figures, there are eligible

about 15,500 draft resisters, 12,500 deserters-at-large (of

whom about 10 to 20 per cent will be ineligible because of other

offenses), and about 200,000 veterans who. received undesirable or

punitive discharges because of offenses under Articles 85, 86 and 87 of the UCMJ. Apparently ineligible are any draft fugitives who are aliens

or who have become citizens of another country. That

is ominous, since in the year 1972-73 more than 3,000

American males became Canadian citizens, an increase

of 82 percent over the previous year. Also ineligible are

eighteen draft resisters not furloughed from prison at the time of the

announcement because of other charges, persons charged with a variety of other violations stemming

from opposition to the war in Vietnam (destruction of

government property, tax refusal, conspiracy, riot, and

so on) and more than 300,000 veterans with other than

honorable discharges that stem from charges or actions

other than desertion (refusal of orders, disrespect, disloyalty, etc.). Ford’s plan, in short, ignores some of the

most principled opposition to the war in Indochina and

the military. Those not included comprise a roster of well-known resistance cases: the Berrigan Brothers; the Chicago 15; the Milwaukee 14; the Presidio 27; Capts.

Howard Levy and Dale Noyd; Seaman Roger Priest

(convicted by the Navy of “disloyalty” for publishing

his underground newspaper, OM, from within the Pentagon); Andy Stapp,

founder of the American Servicemen’s Union, and many, many more.

As for those who are included, the loyalty oath, with

its imputations of guilt and evasion, will prevent the

most consientious from using the program. The oath

and pledge required of deserters is so outrageous as to

deserve full inclusion here:

On or about, _______ , I voluntarily absented

myself from my military unit without being properly

authorized in contravention of the oath taken upon

entering the nation’s military service. Recognizing that

my obligations as a citizen remain unfulfilled, I am

ready to serve in whatever alternate service my country may prescribe for

me, and pledge to faithfully complete a period of _____ months service.

I do hereby solemnly reaffirm my allegiance to the

United States of America. I will support, protect and

defend the Constitution of ! the United States against

all enemies, foreign and domestic; and will hereafter

bear true faith and allegiance to the same.

I take this obligation freely without any mental reservation or purpose of evasion.

Such an oath alone has doomed the program to failure.

An editorial in the Christian Century sums up its implications:

To earn re-entry, a man would have to be contrite,

and to accept his country’s forgiveness for an act of

moral protest. In order to be contrite, he would have

to acknowledge that his moral protest was a mistake.

Ironically, then, a man’s willingness to accept earned

reentry will be inversely related to his conviction that

the war was immoral.

Draft resisters are required to sign a similar oath with

an even more outrageous and ominous addition—they must give up their

constitutional rights.

“I

also knowingly help to deepen the cynicism of the

young in this country.

Apparently, they were not supposed to take Senator

Gooddll’s utterances that the war was immoral seriously

enough to act on them. And what are they to make of

the principles of Father Hesburgh, who resigned from

the Nixon administration and came out for unconditional

amnesty after Spiro Agnew’s plea bargain? Only a few

days before his appointment, Hesburgh joined with other

religious leaders in an attempt to visit President Ford

and plead for amnesty. They were rebuffed, but their

message was, “If leniency excludes certain categories of persons or if

conditions are so strict that few take advantage of the leniency

offered, our nation would continue to have an exile community and an underground

community at home. Consequently, we would not be

united, but divided, and the wounds would remain.”

In a final ironic twist, the program places the alternate

work program under the direction of the Selective Service

System, an agency infamous for its misunderstanding and

abuse of objectors and resisters. It is precisely because

they were opposed to conscription and the punishment

of alternate service for obeying their consciences that

many of these men refused to have anything to do with

the draft in the first place. The rules for administering

alternate service are complex; it is perhaps enough to

note that those who will be subjected to it will lack the

right of appeal and will be subject to the whims of Selective Service for two years.

Given all this—the VFW speech, the Nixon pardon, the oaths, a Clemency Board that can offer no real

relief dressed up in liberal clothes, the legal traps, the imputations of

guilt—it is no wonder that the Ford announcements were met with outrage and disdain on the

part of war resisters. At a conference in Toronto on

September 22, exiles denounced the plan, demanded universal and

unconditional amnesty, an end to the war in Indochina, and called for a

boycott. At home, the National Council for Universal and Unconditional Amnesty

opened new offices in New York City, Atlanta, Denver

and San Francisco to warn resisters of the pitfalls and

get them involved in the total amnesty drive. The ACLU

denounced the program as “offensive in its assumptions

and outrageous in its implementation,” and promised legal

challenges as well as free legal counsel to those covered

by the program. It is their opinion and that of other draft

and military law experts that most men will be better off avoiding the

program entirely, seeking legal redress outside it if they return at all.

The rejection of the plan also took dramatic personal

forms. Draft resister Bill Meis, 29, originally of Decatur,

Ill., became the first exile to return in order to protest

and reject the plan. Meis, who had been in Canada for

six years, is married and has two small children. He

came back with the help of the Safe Return Amnesty

Committee, an effective group that had previously arranged the dramatic

returns of deserters John David Hemdon, Ed Sowders, Lew Simon and others. Meis’s return

was just as effective, with the media carefully recording

his joyful reunion with his parents in Chicago, and his

equally painful failure to gain admission to the Presidential Clemency Board to protest his case. Meis demanded

amnesty for all war resisters before turning himself in

to U.S. Attorneys to face trial. “I am home, but my

exile has not ended.”

Equally dramatic was the refusal of draft resister Steve

Bezich, imprisoned at El Reno, Okla., to accept the

furlough granted those in prison while they await action

of the Clemency Board. Others of the eighty-three prisoners released have also stated that they will return to

prison rather than submit to the clemency plan. The entire

plan, in fact, seems to have stirred up further resistance

and demands for amnesty, rather than put an end to the

problem. The widely publicized first customer of the pro-

gram, John Barry, 22, of San Francisco, turned himself in to U.S. Attorneys, admitting that he had never registered for the draft. However, it was little reported that,

after weighing the implications of clemency, Barry is now

in exile in Canada. Also little reported were acts like

that of James A. Degal, director of the Spokane Center

for World Justice and Peace who, hearing of the plan,

mailed back his draft card and declared, “I stand in

solidarity of conscience with all the peoples of the world

who are oppressed, imprisoned, exiled and tortured for

their moral and political beliefs.”

By October 24, after more than a month of operation,

the clemency program was already clearly a failure. The

Presidential Clemency Board still had only a few hundred cases of those released from stockades and prisons

to consider. Few of the more than 200,000 others eligible

to apply to the board appear even vaguely interested.

President Ford’s re-entry program for Vietnamese War resisters is part of a continuing cover-up of the terrible

costs and consequences of this nation’s intervention in

Indochina. It is designed to discredit resistance to the

war and, along with the Presidential pardon of Nixon,

bring to an end our long “nightmare” of bickering over

Indochina.

Mr. Ford’s August 19th speech announcing leniency

at the VFW Convention in Chicago came as a surprise

to many and was widely reported as a courageous step.

It was neither.

And in Indiana, the Department of Defense closed

down its processing center at Camp Atterbury and moved

it to smaller quarters at Port Benjamin Harrison. They

had discharged 1,419 absentees, only 964 of whom had

surrendered voluntarily. The Pentagon tried as usual to

make it look as if these men were merely immature or

suffering from personal problems. [See Musil: “The Truth About Deserters,”

The Nation, April 16, 1973.1 However, lawyers and counselors familiar with procedures at

Atterbury and Harrison report that alternative service

sentences are lightest for those least opposed to the war or the military,

stiffest for those who take strong anti-war stands.

Whatever a man’s reasons for quitting the

Army, the .Joint Alternate Service Board perceives few

mitigating circumstances other than wounds and decorations. To date, 1,140

of the 1,419 discharged have received 19-to-24-months alternate service. And not all

have been happy about the opportunity. Thomas King,

27, a sheet-metal worker who left the service after basic

training in 1967, was turned in by his wife. “I was op-

posed to the Vietnam war, but I was not a pacifist. I

deserted because it was an illegal war. I don’t believe in

any limited amnesty, but you have no choice.”

There has been one happy outcome of the plan

so far—a list of indicted draft violators has finally been

obtained from the Justice Department at the prodding of

the Center for Social ,Action, United Church of Christ.

The existence of such a list had been denied for years,

but was revealed inadvertently by Justice in a conversation with UCC’s amnesty coordinator, the Rev. Barry

Lynn. Lynn and the United Church threatened a suit

under the Freedom of Information Act and the list was

finally handed over on October 24. The United Church,

ACLU. the Central Committee for Conscientious Objectors and other groups hope to use the list to help fugitives

determine whether they have in fact violated the law.

Amnesty groups are gearing up for more action toward a universal

unconditional amnesty, even before the January 31st deadline. They will

huddle at a National Amnesty Conference in Louisville on November 16-17 to

plot strategy. They believe that Ford’s action has simultaneously appeased those who opposed any clemency at

all, and exposed the inequities and the administrative and

legal hopelessness of any conditional amnesty plan. Once

the dust settles after January 31, amnesty advocates are convinced that

the public will realize that the Ford program was a failure and that total amnesty is the only

feasible and fair solution.

As for President Ford, his attempts to pretend that

the war in Indochina was just’ and is over, that resisters

committed the “supreme folly,” that the draft and military

were free of discrimination, illegality and inequity, and

that our long national “nightmare” has ended, has clearly

misfired. As ‘with the Nixon pardon, President Ford underestimated the

depth and the seriousness, of the amnesty question and hoped it could be quickly and quietly

laid to rest. He is wrong. But like his “last two predecessors,” it may

take some time, and much effort, to convince him of the fact.

Page last revised

09/17/2018

James D. West

www.IndianaMilitary.org