|

Austrian

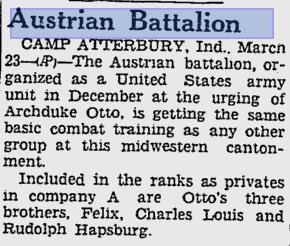

Battalion was part of the regular United States Army which also contained one Czech Battalion and one Norwegian Battalion. Qualifications for this battalion included knowledge of the German language, Austrian parentage. Most were political refugees from the Austrian Republic. After 3 months of service they were given the opportunity to become American citizens. |

||

|

Present Arms -

101st Infantry (Separate) Bn (the Austrian Bn)

Present Arms -

101st Infantry (Separate) Bn (the Austrian Bn)

|

||

|

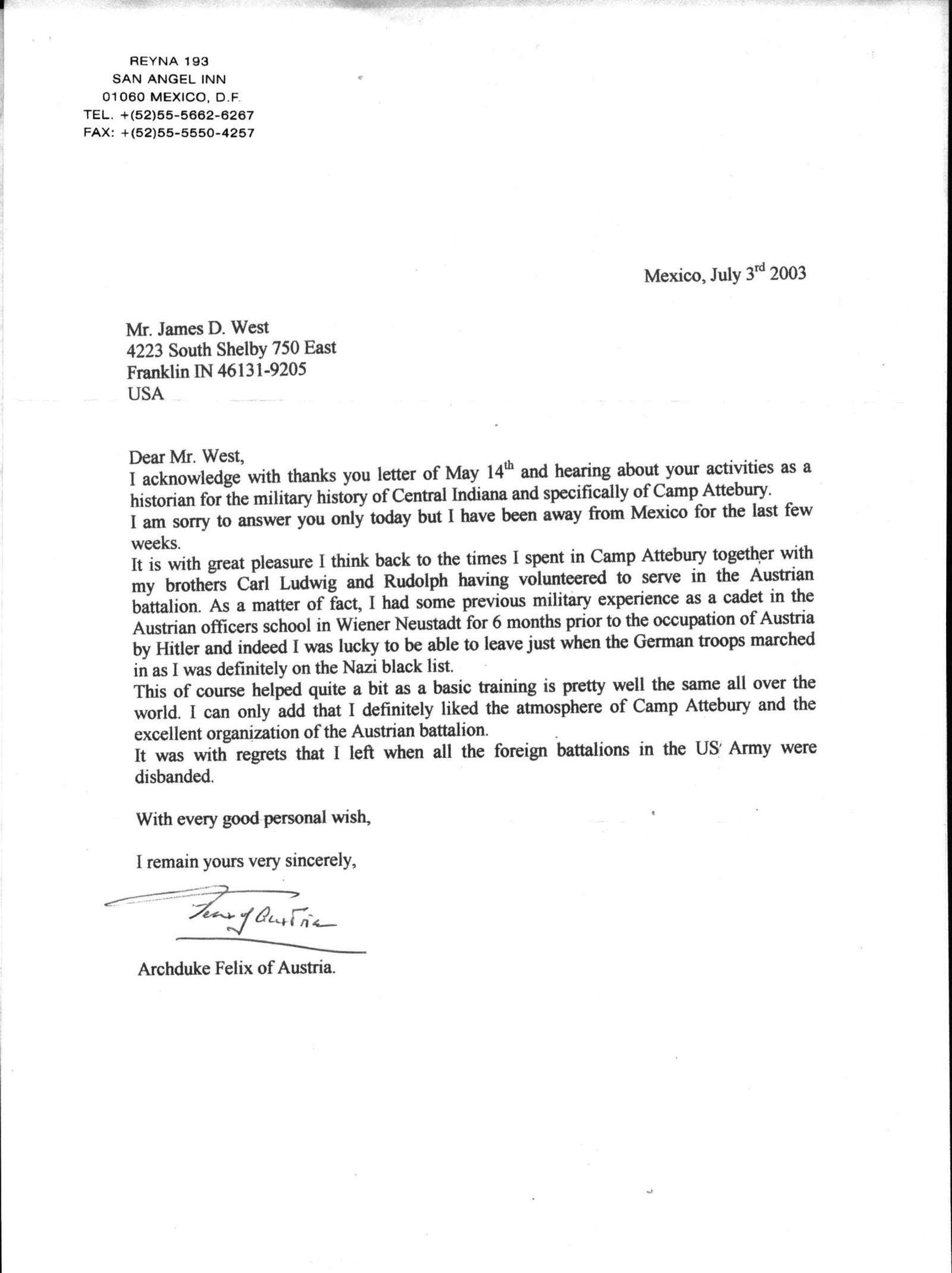

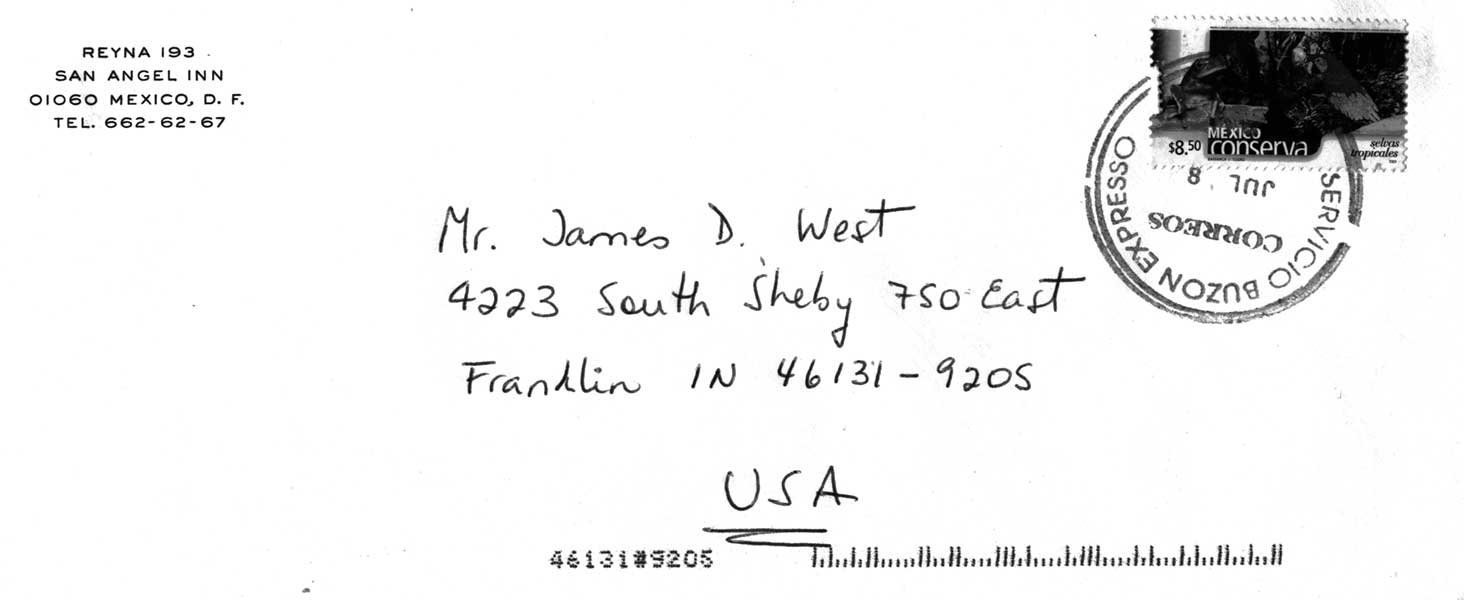

14 May 2003 His Imperial and Royal

Highness Archduke Felix of Austria Imperial and Royal Highness, Please allow me to introduce myself. I am James West, a Historian and Archivist for World War II military history of south central Indiana, USA. I maintain the official website for Camp Atterbury history at www.IndianaMilitary.org . As you know, you and your brothers, His Imperial and Royal Highness Archduke Carl Ludwig of Austria and His Imperial and Royal Highness Archduke Rudolph of Austria trained at that U. S. Army camp with the then newly formed Austrian Battalion. Not much is known about your involvement or activities while at Camp Atterbury other than one newspaper article. I would like to ask if Your Imperial and Royal Highness might like to write of that time period to add to the history of your family and of the Austrian Battalion ? Anything that Your Imperial and Royal Highness would care to send would be most appreciated by me and the many persons interested in that time in history. Any length and any detail. I would be most interested in the day-to-day activities of yourself and the Austrian Battalion, such as schedules, training, entertainment, visitors, trips to Indianapolis, etc. Any photos or documents could only add to the story. I will also write a similar letter to your brothers, in the hope that they will also be interested in preserving details of that time period, Thank you, James D. West |

||

|

Reply from Archduke Rudolph

|

||

|

|

||

The Evening Independent St. Petersburg, Florida 23 November 1942 |

||

Daytona Beach Morning Journal Daytona, Florida 24 March 1943 |

||

|

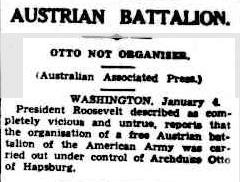

AUSTRIAN BATTALION. OTTO NOT ORGANISER, (Australian Associated Pren.) WASHINGTON. January» *.'' President Roosevelt described as com- pletely vicious and untrue, reports' that the organization of a free Austrian- battalion of the American Army was carried out under control of Archduke Otto of Hapsburg.

|

||

|

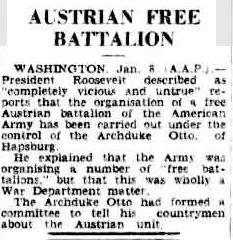

AUSTRIAN FREE BATTALION WASHINGTON, Jan. 8 (A.A.P.). President Roosevelt described as "completely vicious and untrue" re- ports that the organization of a free Austrian battalion of the American Army has been carried out under the control of the Archduke Otto, of Hapsburg. He explained that the Army was organizing a number of "free battalions," but that this was wholly a War Department matter. The Archduke Otto had formed a committee to tell his countrymen about the Austrian unit.

|

||

|

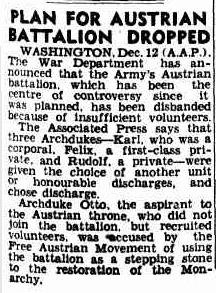

WASHINGTON, Dec. 12 (A.A.P.). The War Department has announced that the Army's Austrian battalion, which has been the centre of controversy since it was planned, has been disbanded because of insufficient volunteers. The Associated Press says that three Archdukes — Karl, who was a corporal, Felix, a first-class private, and Rudolf, a private — were given the choice of another unit or honourable discharges, and chose discharge. Archduke Otto, the aspirant to the Austrian throne, who did not join the battalion, but recruited volunteers, was 'accused by the Free Austrian Movement of using the battalion as a stepping stone to the restoration of the Monarchy.'

|

||

|

Ferdinand, Indiana, USA

It all started with the desperate requests of Simon de Bruté de Rémur, bishop of Vincennes in Indiana, to the Vienna office of the Leopoldine Society (Leopoldinen-Stiftung), an Austrian mission society. From the moment he arrived in Indiana in September 1836, his reports told Vienna of a rather large population of German speakers in his diocese, a fact he had not anticipated when assembling his team of nineteen missionaries. More than a year later, after many letters concerning the insufficient resources available to serve his growing Germanic diocese, de Bruté received word from the Leopoldine Society that a German-speaking priest had volunteered his services. He was elated by this news and wrote to the archbishop of Vienna expressing his gratitude: “With yearning I await the arrival in the near future of a new priest, Fr. Joseph Kundek from Croatia, whose coming has been announced both by Your Princely Grace as well as by himself. It would be most tragic if he changed his mind, for just now I need most of all such missionaries who are familiar with the German language.[1] A Croatian by birth, Joseph Kundek (1810-1857) had learned Croatian, Latin, and German as part of his early training for priesthood, for which he was ordained in 1833. Three years later (1836), he approached the Leopoldine Society with his interest to assist their mission in the United States. His timing was impeccable, because Bishop de Bruté had just recently sent his request for urgent support in the field of his diocese. Father Kundek was prepared without delay and sent, arriving in Vincennes in September 1838. He was appointed to pastor the German immigrant congregation in Jasper, a major town near Vincennes in the neighboring County of Dubois and was installed as the pastor of St. Joseph Parish on the twenty-eighth of September. The congregation of German speakers was already at fifty families, up from twelve just two years earlier. By December 1839, it had nearly doubled, numbering ninety families, many coming from Baden in southwest Germany. Preaching to this settlement in 1838 was not easy in the least, as the resources available to reach out or even to stay at a subsistence level were truly scarce. As Kundek’s biographer Dunstan McAndrews wrote: “The young priest was a sound realist: first, he made the best of what he had; secondly, he reached out for more… To have some means of subsistence, Father Joseph Kundek acquired farm property and hired somebody to work it. From the proceeds of this farm he made his living, since it was clear to him, that at least for some time he could not expect but scant support from his parishioners, not even funds for the most necessary parish developments.”[2] Additionally, Kundek found himself being the only priest for the entire area of southwestern Indiana, which essentially required regular travels exceeding seven hundred miles. “My mission, which I traverse on horseback, is about as large as the territory encompassing Vienna, Preßburg, Schottwein, St. Pölten, and Linz.”[3] It was in this vast tract of land, where “the region is healthful, the soil fertile”, that Father Kundek conceived of the idea of founding little Catholic settlements to ease travel between Jasper and the Ohio river port of Troy. As the area was still largely uninhabited, Kundek searched out the perfect location for his seedling Catholic community to meet his idea of a well-balanced Catholic life that included “blending religion and nature into one”. The landscape he claimed for the Leopoldine Society was a valley “with a gently rising slope to the left leading up to a broad ridge [that] was buttressed against a hill impart[ing] majesty to the gentler landscape at its foot; primeval forest over all created an atmosphere of God's solitude. It was into this valley and onto this slope that the lone missionary projected his mental vision of a new town; he in spirit saw a large church resting serenely up on the ridge, its lofty tower, as it were a mighty finger of God, pointing heavenward[.]”[4] In 1839, five days after the Leopoldine Society had purchased the chosen 1360-acre plot from the United States, Kundek began town planning. He soon reported of the progress made for the new settlement, which would be eighteen miles from the Ohio River and the focus of forty surrounding farmsteads. Two hundred-seventy six lots were drawn and placed on the market on 22 April 1840. And although the first purchases came some days later, Kundek declared the town and parish’s official founding as the twenty-second of April, a symbolic date, as it marked a milestone in Kundek’s mission to encourage German settlers to the area. “My purpose in this was to give the German Catholics greater stability… The land in the vicinity is so good that in general few Catholics are better situated… As for the market, anything can be sold here. Many a German Catholic is agreeably surprised he can travel four, five, or even ten miles in a wooded region settled by Catholic families and discuss matters pertaining to religion without contradiction. Here a German is truly respected[.]”[5] As a welcome sign, Kundek fastened a board to a tree with the inscription “Ferdinand”. He chose that name, because Germans could easily pronounce and remember it. Also, it honored the patron Kundek adopted for the town, Emperor Ferdinand, an original member of the Leopoldine Society. The town of Ferdinand has since thrived, while also managing to maintain its valued harmony with the surrounding beautiful wilderness.[6] The existence of Ferdinand, Indiana may well have continued to be the special secret of her residents had it not been for a recent string of coincidental discoveries. Last March, Ms. Alexandra Leich, a resident of Evansville and a student of Habsburg history, became the messenger of the town’s Austrian and German connections when seeking its etymology and finding precisely that upon discovering the website of Ferdinand’s Monastery Immaculate Conception. She informed her finding to a friend, Ms. Renate Stohwasser of Chicago, who in turn mentioned it over coffee to a patron-of-the-arts friend of hers. Save Ms. Leich, none of them had ever heard of this small, remotely located town Ferdinand. This excitement, enhanced by its special connection to the House of Habsburg, inspired the arts patron, a renowned personality and art historian also of Chicago, who wishes to remain anonymous, to speak of a rare unsigned, but attributed to Leopold Kupelwieser portrait of Emperor Ferdinand of Austria in her private collection, a piece she had purchased in Austria. The circumstances also encouraged her to offer the painting in bequeath to the Sisters of St. Benedict of Ferdinand of the monastery, which enthrones one of the highest hills in the buckling Ohio valley landscape. The nuns accepted the kind gesture. The timing could not have been better. Ms. Leich and Ms. Stohwasser were already preparing for the arrival of a mutual friend, His Imperial and Royal Highness Mag. Markus Salvator von Habsburg-Lothringen, Archduke of Austria. His visit to Ferdinand was initially a private affair, for he desired simply to see the “newly discovered” town named after his great-great-great uncle Emperor Ferdinand. However, the opportunity to include him in a yet developing presentation of the painting sparked the creation of a spectacular event. After a considerable amount of organization, Archduke Markus Salvator agreed to unveil the portrait. The weekend of the 20th of June 2003 was chosen for the grand event, which just happened to coincide with Heimatfest, the town’s annual German roots celebration. Consequently, the archduke was welcomed to Ferdinand with a motorcade tour including a special stop at the Heimatfest. Following a brief visit of St. Ferdinand Church, whose portal is adorned with the Habsburg Double Eagle, local leaders and officials formally welcomed His Imperial and Royal Highness at Ferdinand Community Center. Thereafter, the official unveiling was held before the Sisters of St. Benedict, which concluded with a banquet. It was in this way that Emperor Ferdinand of Austria at last came to “settle” in the town, which had been founded in his name. Accompanying the Archduke were Ms. Renate Stohwasser, Ms. Alexandra Leich, and Mr. Glen Covert, an aspiring scholar of Austrian and Habsburg history and a member of the Austrian-American Society of Oregon, being present on the recommendation of Ms. Waltraut Kindler-Goertzen, president of the Austrian-American Council-Northwest. Further information on Ferdinand or the Monastery Immaculate Conception can be found at http://thedome.org or by contacting Ms. Karen Katafiasz, Director of Communications for the Sisters of St. Benedict of Ferdinand, Indiana, at ++1-812-367-1411.

|

||

|

The following articles have been, for the most part, been translated from the original German into English, using "Google Translate". The translation is not the best, but is understandable. If anyone can translate the documents into English in a better and more accurate manner, please contact me. |

||

|

ARMY-historical MUSEUM wwwcftmlku're and MAft - of the Totenwwa, ld as Krregsjahr 1944 CATALOG TO the SPECIAL EXHIBITION WITH RIDING RISING UP OF In the middle of gave to April 1945 the list of a 6sterreichischen militiirischen unit bekannt1 as tie point of this battalion applied the city Riom in the 1épartement Puy de D6me. The instruction went by to set for em first Detachement of 200 freiwilligen and four "officers ehem6gliclist in march. After the report of Hans's realm man the message was taken up by the list of osterreichischer units in the camp Suzzoni, INIT of grocer joy "; all Lagerangehorigen announced itself to without exception as freiwillige. Since the exact end of the war was to be counted and abzLisehen yet on the list of further battalions, one gave the jungsten Jalirgangen Glen priority for the time being. To 2. Times 1945 sailed itself enter Fiihrung of realm man the first battalion in Algiers an and arrived on 12 May in Riom." There it became with 6sterreichischen freiwilligen to other camps in France on the Effektivst:irke of 501; Man erg.;inzt and remained full four months in training. As 1. Osterreichi battalionbattalion battalion, consisting of three Schiitzenkompanien and of a staff company, formed it a selbst(iindigen, organizational the franz6sisclien army for subordinated federation. This on 14 September 1945 in march set and reached end of the monthly Innsbruck, where the 1-I6cllstkommandierende of the franz6sischen zone of occupation in eastreach, general Bethouart, in 10 October the Defilierung of the battalion before the yard castle decreased. In the consequence the battalion, whose companies were befehligt by Osterreichern, provided the border service in Vorarlberg together with franz6sischen units. But p16tzlich and v6llig verNigte unexpectedly the inter+allied advice on 14 December 1945 the Aufl6sung federation very much to the Enttauschung of the freiwilligen, who hoped, this battalion wiirde once the core stick of the army of the free and selbstiindigen eastreaches hilden A ' the end of war prevented the list of further 6sterreichischer of battalions. Remaining in the Camp the Suzzoni Zurtickgebliebenen, which likewise still with the employment in unitunit units had gerecllnet, to at the beginning of of 1946 in its North African camp and divided here as well as after their transfer after Siidfrankreich the fate of other Wehrmachtsangeh6riger than Kriegsgefangene.'1 United States with the war entrance of the United States of America at the beginning of of December 1941 began also the freiwillige message 6sterreichisclier of there Fluchtlinge to American army altogether diirfte the number of the free the willing and drawing in between 3000 and 45001iegen 49 your motivation to this step covered itself groBtenteils with what was said already a while ago to it: Anti-fascism, gratitude more gegeniiber the host country, possibly faster and easier acquisition of the new Staatsbiirgerschaft, not last also of the 6sterreichischen exile organizations publicised contribution for release Osterreichs. This 6sterreichischen soldier was distributed on the most different units and Kriegsschaulilatze, not few by them worked due to their intimate knowledge of the opponent in teams of the Psychological of throwing acres Branch and/or division or the militarischen secret service Office OF Strategic services (OSS). An attempt to set up within the American army its own sterreichische combat unit failed kllglich. The Austrian Battalion (101st infantry battalion of the 2nd US army) and CIBs dafiir since 19 November 1942 t~itige?Military Committee for the Libe ration OF Austria "went, like Peter Eppel in a ausfiihrlichen Ana lyse of the available sources and representations pointed, to s" last to an initiative petrol have castle from at the beginning of of February 1942 zuriick, which found dafiir in the amerikani schen Prfisidenten the starksten Befurworter on the part of the American administration. Fiir Roosevelt had such a federation symbo a lischen character, like this also with ahnlichen Auslanderformationen (Greek, Norwegian, Philippinos) the case was pure; the militfirische value stood fiir it, who already with a company, thus ungeffihr 120 men, zufrie dengegeben themselves had, hardly to the debate. Roosevelt became generally accepted in the question Osterreichi battalion despite serious doubts from the being and the State department particularly also because of an official acknowledgment of the Rckrutierungskomitees and of the associated role of petrol Habs castle. On 19 November 1942 war Minister Stimson in a press conference communicated the intended list of a Osterreichi battalion in the Ralimen of the American army, and he also determined thereby, daB that was department the assistance have castle offered by one?Military to Commit dte "Linter presidency petrol with recruiting of freiwilligen fiir the battalion assumed. The purpose of this troop is to show the Osterreichern in the whole world daB the egg nigten states decided was, eastreaches to release. On the same day also mentioned recruiting committee began to send country-wide calls at military requiring Osterreicher away; they demonstrated co-operation specified by Stimson between were department and petrol Habs castle recruiting committee; the acquisition of the American Staatsbiirgerschaftwurde fiir Bataillonsangehorige after three-month service in prospect posed; the safety device of the liberty of all Volker of the Danube area goes inseparably connected is "around release 0sterreichs, blow it?mit to that;' ' thesis of calls?Military Committee "yon of the petrol having castle and persons of its confidence was signatory. On thesis Ankundigungen and due to the Verquickiing of the battalion with having castle broke loose Linter the osterreichischen emigrant and with representatives of the succession states a storm of the Entriistung. the laboratory Committee "with Julius German and Ferdinand Czernins?Austrian Action" geliorten to the most violent Opponenten. W;ilirend Czernin nevertheless ftir a battalion and a recruiting committee on unpolitical basis occurred, rejected Julius German grunds1;itzlich jecfe osterreichische troop unit, because he hind its Anhanger open the option of the whereabouts with rough Germany to keep himself wanted. and informed amerikamsche journalists referred German alarmed representatives of the succession states, suehte and find Riickenstiitze with Assistant Secretary OF StateAdolf A. Berle Jr. to the schlecliten experiences of the Englandermit alinlichen units in the pioneer corps. Under these Dorothy Thompson was, clurch their Artikcl and radio endings against the battalion the case only a national dimension in the United States annalim. In less than two weeks medium campaign come into course, the all other Aktivitc;iten of the osterreichischen Fliichtlinge in the USA at Publizitlit I[ibertraf.5'Wie Czernin and other organizations (?Assembly for A Democratic Austrian Republic "?Free Austrian Youth") Much representatives of the succession states anything did not have to object be-being one to a 0sterreichisches battalion, however vie ] to petrols have castle recruiting committee, in particular as if, daB yon this also Poland, Czech, Hungary Lind Slowaken, thus elements of the Danube monarchy in ruins, oozed adjusted was. All thesis oppositional groupings Lind Reprl~isentanten of the succession states signed on 1 December 1912 a call against the planned battalion. Thereupon were that was department and of the President in the course obligation. Stimson erklarte, for recruiting yon freiwilligen given to no special osterreichischen group of SE i the ausschlieBliche right, those assistance of all Personlichkeiten and organizations was erwiinscht, and petrol have castle committee a private association and not yon the American government had been ordered (press conference from 26 November 1942, Erkkirung from 9 December 1942). Roosevelt pointed in its conference of 5. j-*inner 19431m WeiBen Ii from report, according to which petrol having castle checks the battalion, when?boswillig and erklarte untrue "zuriick and, each respectable osterreichische committee has the same Moglichkeiten. But the attacks went to far and beschaftigten also the KongreB. Press and politician fiirchteten, who prajudizieren bloBe existence of the battalion the wiirde postwar planning of the Allherten. thus it seems ", wrote for example Johannes Steel in its?New York Post"column?Steel filings", daB Mr after the vor0bergehenden acknowledgment Darlans as a civil governor yon Franzosisch North Africa also a Habsburger as potential i-lerrscher of a released 0sterreich recognizes now. It wire indeed with difficulty, to i.iberzeLlgen (lie geknecliteten europiiischen Volker of it, daf; this politics for the reconstruction of Europe on democratic basis wiirde fiifiren."' ' The battalion was of was department as an American connecting with osterreichischen freiwilligen planned, which should have the same rights as soldiers of other Verbiincle. In the training stage the officers American Biirger osterreichischer descent wiirden its, his clann at present the employment 0sterreicher thesis positions to take could. Genfgend if freiwillige should not be found, one thought of the transfer of osterreichischer emigrants from other units. The soldiers wiirden the oath on the United States carry out, for amerikanßche army uniforms and crimp possibly Mr the American Staatshiirgerschaft carry qualify. The battalion was not gedaclit as combat and as Besatzcingstruppe. As planned, the training of the Osterreichi battalion began on 15 December 1942 in the Camp Atterbury, Indiana. As open kundigwurde, da(3 the battalion with freiwilligen do not aufzufilllen were, wur that for instance since at the beginning of of February 1943 American Staatsbiirger osterreichi do not shear provenance and osterreichischeEmigranten from other units in the battalion shift-officially with agreement of the concerning, but in many Fiiflen Much against their will. Few that altogether 588 soldiers (conditions center Marz 1943) were Angehorige of the succession states - Linter other 30 Tschechoslowaken, 27 Poland, 21 Yugoslavs, 19 Hungary -, and thaw report of the commander of battalion lieutenant colonel Vincent J. Conrad grassierten discontent and of resentment Linter the Nationa litiiten. Soldiers betracliteten the battalion as vehicles fiir riclitung i-labsburgerherrschaft in Europe (?I don't want ton fight for Petrol. I want to fight for America."), '1 befiircllteten by the transfer a Verzogerung of their Ansuchens over (lie Staatshiirgerschaft or was simply to have been veriirgert, from ilirem friiheren militt;irischen federation have been pulled out. Due to darauflnn the breaking loose protest fiber (lie obligation transfer Stimson in the MI;irz granted 1943 (lie Riickversetzung all that one, insisted on on which tats;ichlich in the Haupisache _ (lie Volontare iibrigblieben beginning of April 1943 was this 144 men. The intended battalion-strong from 931 soldiers to to erreiclien seemed with the available recruiting speed only in zwcieinlialb years realizable too sein.ss an attempt of the Habsburganhlinger, cine damage delimitation by a reader letter action roughput on lrerbeizuNihren, failed due to opposing upper power and of the too sp:iten time, why the Clef of the general staff in the middle of nalielegte April 1943 the Auflosung. Roosevelt gave its consent, and beginning mark 194) was issued the order to register the battalion in such a way fast wic m6glich un(1 without offentliche Ankiindigung too liquidieren.sb serious errors and FehleinschIitzungen cattle on sides of the amefkanischen administration as well as the RH of krutierungskomitees which were the focus of all attacks. It, the American Offentlichkeit and to iiberzeugen (lie osterreichisclren emigrants of a clear separation - here 0sterreich-Bataillon, there 1-fabsburgaspirationen - did not succeed of the two. The?Free Austrian Youth Committee ", which was close to Ferdinand Czernin, driickte its Mil3billigung clearly out: we bind flberzeugt, da13 you fur the interest of your family argue and not fiir (lie release 0sterreichs. [... ] you storen the unit, (lie we straight in the war against the axle-made so urgently brauclien."s ' heiBt, the name having castle stood now for for Demokratiefeindficlikeit, fur Unterdriickung of national Unabliangigkeitsbestrebungen, for a Beeintriiclitigung of the fight against Hitler angesiclits the quietest suspicion, more daZner down lagedes third realm monarch a istische restoration follow wfirde. It Avrde verabsaumt, other osterreichische exile organizations, which offered themselves as xAtzliche recruiting forums to merge. And it became hardly ad positive and negative experiences with battalions of g:eser kind already bestelienden zurfickgegriffen; the Offentliclikeitsarbeit existed as well as,;cht, the Ankiindigung fiber the list of the battalion and of a recruiting committee came so plotzlich, as if one wanted all iiberrumpeln tnd considering vorausselibarer protests before completed facts stell;n, too strongly on Roosevelt was set, sodafl one believed, on further Aufkliirungsarbeit do without to konnen. Serious questions, how those that in the case of the capture of the Bataillonsangehorigen by the third realm wiirde - capture as Hochverrtiter - and as one geschefien before it to be secured could, not enough were considered. Just as little one took Rticksicht on the desire many osterreichischer emigrants in the United States, which ansalien the acquisition of the American Staatsborgerschaft fiir more importantly than the recovery of the Unabhangigkeit of the homeland state often not remained in best memory.' " It surprised finally, daB the number of the freiwilligen expectations did not to-tick-remain far more enter. Jt1goslnivien "as (lie fiinf 0sterreichischen of battalions trained warden and/or one as the employment came, was the power situation on the Balkans and also in the in satzgebiet into Slovenia already for the disadvantage of crew power ent separated. Sclion since the surrender of Italy in September 1943 and of the Ubernalime of the area controlled before by Italy saw themselves, gro(3raumige Umfassungsmanover Lind operations forced to military making Lind Polizcitruppen in favor of limited regional employment as well as control of Stiitzpunkten and connecting lines zurfickzustellen; began at the same time also at that time verstarkt (lie allied Unterstfitzung ffirTito. At the end of of 1944, as (lie training of the Ith Osterreichi battalion as the AbschIuB came, was also the area around Crnomelj and the Suha Krajina already Nebenschauplatz of the German Partisanenbekampfung. In ' ~, rnomelj i-lauptstab the volume of CCB free army and of the part lay isanenabteilungen Slovenia un(1 not far of it - into tributes - the training camp of the Ith battalion. The periphery Crnomeljs formed its area of operations. 1-tier went it around repelling small mobile raiding parties of crew power and gleiclizeitig the basis to the north to secure, whereby the Krka between Zuiemberk and Novo Mesto ifberschritten only rarely became. Facts sci this representation placed in front: Yugoslavia was the only country, (read osterreichisclien units the employment ermoglichte; their list is not conceivable without the history of the communist emigration Osterreichs, or, like it Willibald Ith Holzer formulated, the communists was?weitgehend with the Bataillonsgrondung under itself "6 ' the battalions, (lie fiir (lie Alhierten like also fiir (lie Yugoslavs to time |

||

|

Documentation archives of the Austrian resistance (Hrsg.) More tha

From contents |

||

|

Kroiher, Erik Sidney Aspects of the involvement of the House of Habsburg in the activities of the Austrian Resistance 1938 – 1945 BIBLIOTHEK Dokementationarchiv Des osterreichischen Widerstandes Contents

Abstract When Austria was occupied by Nazi Germany in March 1938, the House of Habsburg who ruled Austria until 1918 became actively involved in resistance activities against National Socialism. Their actions have caused different interpretations ever since. Whereas some historians propagate the thesis that the political work of the Imperial Family was of the greatest significance in the eventual rebirth of Austria, others argue the opposite case. Many opinions are based simply on general attitudes and emotions. In this essay I will try to discuss the actions of the Habsburgs during the period from 1938 – 1945 with reference to both internal and external events by using information from documents, original newspapers, interviews and books. I will pay special attention to the relations of Archduke Otto von Habsburg with the Schuschnigg government before and after the invasion, the Habsburg intervention in France between 1938 and 1940 and the reaction of the Daladier government. The contracts to the British government and American authorities, especially President Roosevelt will be examined carefully. A discussion of their achievements as well as their failures and of the role of the Imperial Family in the organization of the Austrian resistance will bring me to the conclusion that the House of Habsburg indeed played a significant role in the process of Austria’s rebirth, although I should not consider a single group to have been most important in the resistance and agitation as I believe cardinal measurements of that kind of historical events is not appropriate. Essay In the eyes of many people, the Habsburg family had vanished from the stage of world politics in November 1918, when the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy collapsed. This assumption becomes rather disputable if one is examining more closely the political events that followed the First World War. Especially the period of the Nazi-occupation of Austria and the Second World War shows considerable activities of the Imperial Family particularly in the fields of diplomacy and in the organization of resistance against Hitler. However many historians hold very different opinions as to the success of these activities and their significance. In this essay I shall be trying to display a picture of the Habsburg efforts in fighting Nazism. Which is based on mainly primary but also secondary sources to set up an evidence-based evaluation. Before entering the process of investigating the time from 1938 to 1945 it is necessary to give a brief history of the House of Habsburg-Lorraine (Lotheringen). The dynasty’s origin reaches back in history as far as 1273, when Rudolph I of Habsburg was crowned German King. With a few exceptions, the title remained in the family. Finally in 1452 Fredrick III was crowned Roman Emperor ---------- the House of Luxembourg. The Habsburgs continued to be the sovereigns of the Holy Roman Empire until 1806 when Emperor Francis II proclaimed the end of Charlemagne’s Empire, as in anticipation of which Leopold II’s successor Francis II had in 1804 begun to style himself hereditary Emperor of Austria. The House of Austria possessed vast areas, too, which were their hereditary dominions since the family’s possessions had been divided between the Austrian and the Spanish line in 1556. Therefore at the latest since Queen Maria Theresia of Hungary and Archduchess of Austria etc., her dominions had established themselves as a powerful unity. Through Maria Theresia’s marriage with Francis Stephen I of Lothringen who was elected Roman Emperor, the family name became Habsburg-Lothringen. From 1700 to 1866Austria was a most influential Great Power. But after that time Austria, or, to be correct, the Austro-Hungarian Dual Monarchy (1867) was slowly but constantly declining, after a series of political and military defeats and growing unrest within he country. In 1889 the Empire lost its heir to the throne, Emperor Francis Joseph I’s only son Rudolph, who either committed suicide or was murdered – an incident which has not yet been cleared up completely. The aging Emperor’s nephew, Archduke Francis Ferdinand, who became pretender to the Imperial and Royal throne, was assassinated in Sarajevo on June 28th, 1914. Consequently, the First World War was triggered off. In 1916 Archduke Otto von Habsburg’s father, Karl, became Emperor of Austria and Apostolic King of Hungary and therefore his eldest son Otto the heir to the throne of the empire. After the collapse of the Danube Monarchy the Imperial Family was forced to leave Austria on November 11th, 1918. However, the emperor “only refused to take part in any governmental affairs but did not really abdicate.” (2) The Emperor, his consort and their children went via Eckhartsau Castle into then Swiss exile in 1919. One year later, the Emperor, who was also Karl IV of Hungary, made two unsuccessful attempts to restore the monarchy in Hungary in March and October 1920, which resulted in his deportation to Madeira, where Emperor and King Karl died a few months later, on April 1st, 1922. The Imperial Family was banned from visiting Austria and their property was confiscated by the new Republic. In the years between 1922 and 1938 the Habsburgs lived in Lequeto in Spain and in Steenockerzeel in Belgium. Besides close contacts to the Austria and Hungarian legitimist movements, the Habsburgs did not directly try to intervene in the current political affairs of Austria. This changed immediately with the growing danger of an annexation of Austria by Nazi Germany in the second half of the 1930’s. The events that took place in the last few years before the Anschlub. The Schuschnigg regime came under continuous pressure from both interior and exterior forces. Italy’s support for the government of the “Patriotic Front” (VF), which represented a system similar to Mussolini’s fascist state, was diminishing as the relations between German and Italy improved. As a result, Austria was becoming more and more isolated in her diplomatic battle for securing the country’s independence from Germany. Austria was faced with a major campaign organized by Nazi Germany with the aim to prepare the country for a Nazi-takeover and to weaken the government. The Western powers were not to sympathetic towards Schuschnigg’s Patriotic Front either, as it exercised a rather authoritarian rule and had in the recent past often supported Italy against Britain and France. Internally, public discontent was growing too. Two strong groups were strictly opposing and, indeed, campaigning against the Chancellor’s single party system. The Social Democrats on one hand and the German Nationalist/Deutechnationals together with the Nazi Party on the other. Although the Social Democrats strictly opposed Hitler, the idea of the >>Anschlub<< was supported by leading Socialist politicians (April 3rd, 1938) in an interview wit the Viennese newspaper >>Neus Wiener Tagblatt<<, the former Chancellor of State, Dr. Karl Renner approves of the so-called plebiscite determining Austria’s incorporation into the German Reich (>> vote in favor <<)(3). The leader of the “The organization of Revolutionary socialists”, the exiled Otto Bauer, expressed the view that “…the victory of Socialism could not be fulfilled by the reactionary desire to re-establish an independent Austria but only be the panger man revolution”(4). Here it is necessary to add that there were also leading socialists such as Heinrich Allina and Karl Hartl who were totally against the >>Anschlub<<. The Nazi Party was, of course, the strongest pressure group calling for Austria to be incorporated into the Reich as soon as possible. Both camps were forbidden by the government consisting of the two right wing organizations of the Christian Social (>>Christlichsoziale Partei<<) and the >>Heimwehren<<, the latter a paramilitary patriotic group. Also within Schuschnigg’s own ranks there were numerous influential people who fancied an integration of Austria and the German Reich. Faced with that situation, Schuschnigg got in touch with the head of the House of Habsburg, Otto. The Chancellor seriously considered Otto’s offer to take over the chancellorship on February 17th, 1938. As legitimate successor of a dynasty which ruled Austria for 650 years and as the son of my late father,… it is impossible for me not to face what is my inherited duty… I would like to encourage you to hand over to me the chancellorship so that, without changing the constitution, the situation would be as advantageous as it would be through a formal restoration of monarchy … (5). This indirectly also stressed Otto von Habsburg’s claim on the Austrian throne, a fact that would cause many disputes in the future. However in 1938, the monarchist Schuschnigg saw Archduke Otto as the only person who could manage to unite the resistance against Hitler’s obvious plans to annex Austria, and, due to the Archduke’s good relations with many foreign politicians, as the only person to get support from the Western Powers. But the Archduke had many opponents too. Especially Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, and Romania opposed a return of Habsburg to Austria. Military intervention of these powers in reaction to such an event seemed not to be impossible. Schuschnigg’s claim, the only reason why he supported the Legitimists was to provide an area of resistance against the Nazis, did not justify many other governments, either (6). However, Schuschnigg did not decide to let Otto von Habsburg take over governmental responsibility (7). Meanwhile, in Germany, Hitler was very much aware of the political threat to his expansion plans which was posed by a possible return of Habsburg to Austria. Therefore the >>Anschlub<< was given the code name ..Operation Otto<<. Hitler wrote in a letter to the German High Command,

Indeed, one day after this message, the troops of Nazi Germany (Hitler’s 8th Army) invaded Austria. The Schuschnigg cabinet had resigned the night before and ordered no open resistance to be undertaken against the Germans (“Ich weiche der Gewalt”) (9). Besides, great parts of the population approved of the >>Anschlub<<. The political Engagement of the House of Habsburg in Europe The evaluation of the Habsburg involvement in organizing resistance against Hitler is still an object of quarrel in the opinions of different historians; especially the views of Austrian experts on that issue are deeply divided. There are two main approaches to the question of Habsburg involvement in Austrian resistance. A group of historians propagate the thesis that without the diplomatic efforts of the House of Austria the country would not have been resurrected after the war. A supporter of this attitude is Professor Erich Feigl who proves by the use of documents, letters and interviews that there was nobody in Austria who contributed so much to the defense and to the resurrection of Austria as Otto and his Family (10). Another group holds the opinion that Otto von Habsburg’s interventions were not very significant and did more damage to Austria than they helped the country, “Otto Habsburg’s efforts mainly served the purpose to restore the monarchy and to re-establish pre-World War One conditions” (11). These two statements show clearly that there exists a major problem in the historical evaluation of the activities of the House of Austria. It is therefore necessary to investigate the nature of the events between 1938 and 1945 from a barely factual point of view before conclusions can be drawn. As soon ad the >>Anschlub<< was proclaimed and the Austrian justice system was replaced by the German, Otto von Habsburg was declared a traitor and a warrant was issued. Otto, who had been staying in Switzerland for the last few weeks before the German invasion, left for France and got in touch with French officials. His main concern was to secure the Western Power’s support for the resurrection of an independent Austria State. His brother, Archduke Felix, who had been attending the military academy of Wiener Neustadt, managed to leave Austria immediately after the >>Anschlub<< through a secret diplomatic intervention of the Hungarian Embassy. Archduke Robert, Otto’s and Felix’ brother, meanwhile went to England to get in touch with the Foreign Secretary Lord Halifax. Due to the intervention of Prince Felix of Luxembourg who was a friend of Lord Halifax, the Lord agreed to help in persuading the German authorities, who then were interested in being on good terms with the British, to allow leading members of the Austrian Legitimist Movement to leave the country. Through that way many people who had already been arrested by the Nazis could be released and continue their efforts against Nazism from abroad. To the better understanding of the political scene in Austria it is important to explain the nature of the Legitimist Movement. This was an organization of people who worked for the restoration of monarchy as they believed this type of system was the righteous one and the best to secure the peaceful development of the state. “In theory, legitimism differs from the notion of monarchism in so far that monarchism is a general political theory, whereas legitimism (lex, legis-moral, divine right) can be characterized by its supporters’ loyalty to the ‘legitimate’ heir to the throne, their sovereign. This difference, however, played a very little role during the time of 1938 and 1945. (12)”. The legitimists were by no means opposing the principles of democracy in terms of governing a state, but believed that it was the Devine Right of a king to be the head of state. It is easy to explain why they were against Nazism: The Nazi propagated a totalitarian state in which the government, the head of state and the ideology had to be universal and had to rest in the hands of the same people. In the Nazi’s views the former system had to be abolished and society was to be transformed in a revolutionary way. Legitimists saw no future in radical change and opposed revolution. Furthermore, total power and the concentration of all responsibilities and bodies of a state in the hands of a simple group was very suspect to them, as in their view the prosperity of a country depended on these conditions: The church, the dynastic principal of monarchy and the democratic system of a temporarily elected government (although their major concerns were the first two). For all these reasons the legitimists were fierce enemies of the Nazi dictatorship. The people most respected by the representatives of legitimism were the members of the House of Austria in which they saw their sovereigns. To large parts of the resistance, Archduke Otto and HM Empress Zita therefore became the symbols f opposition to the Nazi tyrants. The members of the Imperial Family had various fields and places of work. Archduke Otto was, as I mentioned earlier, getting in touch with leading French politicians such as Daladier. It was made clear that the Habsburg interventions, although being pushed forward by people of a monarchist background, “didn’t regard the necessity of the restoration of the monarchy as a condition for their work” (13) Prime Minister Daladier agreed that an Austrian military unit could be established within the French Armed Forces and a very detailed plan was set up describing the nature of that unit. The legitimist resistance coordinators were also allowed to issue their own newspaper, >>Die Osterreichishe Post<<. Daladier’s support for the Habsburg cause, the resurrection of an independent Austria, finally mounted in France’s declaration of a free Austria, based on the declarations of the League of Nations on February 17th, 1934, September 27th, 1934, the Stresa Conference on April 14th, 1935 and finally, the Anglo-French declaration of February 3rd, 1935, in which all acknowledged the absolute necessity of an independent Austrian state. While in France and Belgium, the Austrian Emperor’s eldest son also established his links to the monarchist resistance groups within Austria. In the beginning there were three major assistance groups which were led by Baron Karl Burian, Wilheim von Hebra and Franz Waschnigg. “The active core of the Legitimists was composed of the nobility, former World War One officers, and some Catholic clergy. There was a good deal of personal and ideological continuity in the clandestine work.” (14) Although battered by the Gestapo (Burian and Hebra were arrested together with some 200 Legitimists), the resistance groups, who were in constant touch with Otto von Habsburg, managed to be active throughout the entire period of occupation. The monarchists (it was at this time possible to use the terms monarchist and legitimist alternatively for the Habsburg oriented resistance) in alliance with other groups opposing the Nazi dictatorship such as the Roman Catholic Youth and Social Democratic circles, were apart from bringing oppositionary propaganda into circulation, successful in organizing public actions. “After a football match in autumn 1938 (>>Rapid<< versus >>Schalke 04<<) a great demonstration against the >>Anschlub<< was launched of which we knew in advance.” (15) In Winter 1938/1939 the different groups of Monarchist resistance were partly assembled within the >>Free Austrian Movement<<(FAM), where the names of Roman Scholz and Adolf Worobil, who did a great deal of coordination, must not remain unmentioned. The central leadership waas claimed by Johann Muller, who headed one of the most significant monarchist movements. Although many close contacts existed between the different groups, such as the FAM’s connection with the so called Mayer-Thanner network and their cooperation with the Catholic peasant circles, it would be wrong to assume that there was a centrally unified monarchist resistance. The only two people who can be considered to have been central organizers were Archduke Otto and Franz Waschnigg. “However the broad base of the movements also left them vulnerable to Gestapo informers.” (16) As mentioned previously, the monarchist groups, which also often worked together with other resistance circles even the Communists, were of considerable danger to the Nazis, as they admitted themselves. Above all the clericals and the legitimists must be viewed today as our truly active opponents.” (17) Achievements on governmental bases As the Austrian Head of State in 1938, President Wilhelm Miklas, had refused to dismiss the Schuschnigg government and therefore not appointed Arthur Seib-Inquart, a high ranking Nazi leader, as new chancellor, the conditions for the Austrian Constitution were not satisfied. The chancellor had dissolved his own government and allowed Seifb-Inquart to form a new one. A fact which is illegal according to the Austrian Constitution of 1929. So, in theory, the former government was still in office. This has often been denied by other politicians and some historians, but was constitutionally in order. Otto, reaffirming the illegality of the >>Anschlub<<, attempted to set up an Austrian government in exile, which was seen to be a vital step in order to safeguard the national independence. As almost all members of the Austrian government, including both Schuschnigg and President Miklas, were imprisoned, the oldest and highest ranking member who was in exile, Hans Rott, was to takeover the government in exile until the restoration of the normal order (18). However, the Socialists never accepted the memorandum because of their firm opposition to the authoritarian right wing Schuschnigg government. It also failed to gain international recognition due to the quarrel over its legality which was going on within the Austrian emigrants. Archduke Robert’s field of operation was England, where he immediately got in touch with the British government officials. Later on an application to join the Royal Air Force was granted by the Ministry of Aviation (19). The Archduke’s main objective was to get British assurance of their determination to reinstall an independent Austria after the war. But in England, unlike in France, the official reaction towards the Imperial Family was initially very cool, although their political and social rank was acknowledged. For a long time the Foreign Office refused to arrange a meeting between Robert and Prime Minister Winston Churchill (20). However, Winston Churchill’s attitude towards the House of Austria and their political aims was rather positive, and there exists evidence that British officials, especially Anthony Eden, deliberately destroyed contacts between Britain’s Prime Minister and the Habsburgs (21) for reasons which will be discussed later in the essay. In an autobiographical note Otto writes “The importance of my brother’s tireless work in London … can not be over-estimated. Robert … had to deal with one of our bitterest enemies. Anthony Eden who had absolutely no desire for a restoration of Austria. The fact that England finally supported the pro-Austrian policy is due to Robert’s work with Winston Churchill (22). Meanwhile, the Habsburg Family had to move their headquarters from Steenockerzeel and Paris over to the United States, as Belgium and France were conquered by Hitler’s invading armies. In fact, the family managed to escape just in time, and the Nazis particularly searched for the House of Austria. Another important factor that has to be dealt with, is indeed the financial side. Where did the financial supplies come from that enabled the Habsburgs to continue their battle against National Socialism, since the family had been deprived of property in 1918 ? It is quite difficult to come up with a definite answer as this has not been covered by many documents or books, but one could divide resources into two different groups. Due to Emperor Karl’s and Empress Zita’s direct family relations to the Royal Families of Belgium and Luxembourg and to many very wealthy members of Europe’s high aristocracy, money was provided from these people. On the other hand, many influential financiers among those many Americans, sponsored the Habsburg cause. Here … the Rothchild family should not be unmentioned. In these matters Empress Zita played the role of a go-between. The Habsburg resistance was coordinated by the head of the family, Otto, and every member of the family had to fulfill a certain task. “Otto’s political activities were based on a teamwork with his brother Felix in Lisbon, Robert and Karl-Ludwig. Karl-Ludwig spent the whole war time in Lisbon, apart from the first part of 1943, when he served in the >>Austrian Battalion<<. There he was the contact person between the monarchist resistance in Austria and Hungary on one hand and the exiled monarchist on the other (23). The Political Engagement of the House of Austria in the United States and Canada Another field of operation was America. In 1940 and again from 1943 to 1945 Archduke Otto and Empress Zita stayed in Washington and New York, following an invitation of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Assisted by two of Otto’s most faithful confidants, Count Alexander Pallavichini and Count Heinrich Degenfeld, the >>Free Austria Movement<< was established in the USA to represent the Austrian Legitimist resistance there. This organization was opposed by the republican >>Austrian Action<< in which Ferdinand Czernin was a leading character. The latter was a confidant of Edvard Benes who was the most defiant enemy of the Habsburgs. Benes is often considered the leader of the “Anti-Habsburg-League” in the USA and in the United Kingdom. Nevertheless, the contacts between the Habsburgs and the president can be described as very good. The circle around Otto and the Empress, consisting of members of the former government and the aristocracy, such as Count Richard von (portion of sentence illegible) Bruno Walter. The political agitation mounted in the US government’s declaration of July 25th, 1942 in which the illegality of the >>Anschlub<< was acknowledged and the restoration of the Austrian state made an official war aim. “This government has never taken the position that Austria was legally absorbed into the German Reich (24).” After that even the British government’s Foreign Secretary, Anthony Eden, declared that “His Majesty’s government does not have to accept the constitutional changes in Austria after March 1938 (25).” In other words, the positive US reaction to the Habsburg interventions produced a more friendly attitude of British government towards Otto’s cause. Strong support for the Habsburg came from influential Jewish circles in America. Many Jews were very favorably disposed to the Habsburgs due to the protection which the Jews had enjoyed during the times of the Empire. The FAM (Free Austria Movement) established a newspaper, the >>Voice of America<<, published by Martin Fuchs, Erik von Kuehnlt-Leddhin and many others. To summarize, the echo the Habsburgs received in America, was very positive indeed. They gained the President’s personal support, were assisted by many important groups and enjoyed the benevolence of large parts of the population. However, the Archduke’s plan to set up an >>Austrian Battalion<< following the same attempt which had been made in France two years earlier, failed. “On November 9th, 1942 the American Secretary of War, Henry L. Stimson, announced the formation of an >>Austrian Battalion<< within the US Armed Forces. However, the >>Independent Infantry Battalion No. 101<< only lasted a short time (26).” The Austrian military unit, although strongly supported by Roosevelt and General Sikorski, the leader of the Polish government-in-exile together with numerous other Socialists. The number of Austrians who agreed to join the battalion was not sufficient, either. Therefore the unit was abandoned and its members dismissed. In Canada, where Empress Zita and her sons got in touch with government officials, their efforts were crowned with considerable success, and the FAM as well as the Imperial Family were given the opportunity to continue their work against Hitler and for the Austrian rebirth. In Earl Athione, the general governor of Canada, the House of Austria found a powerful supporter. The Empress and Archduke Rudolph stayed in Canada for most of the war, but most of the monarchist agitation after 1941 took place in the United States which “…consequently became the centre of the monarchist activities in exile (27).” The Opponents of the Habsburgs and their reasons for the agitation – which were the omissions of the Imperial Family Besides their obvious enemies, which were the Nazis and their allies, the Family’s work was opposed by various other political groups. As I mentioned earlier, the Habsburgs did not win many friends among the Revolutionary Socialists or Otto Bauer which was a quite important group within the Austrian political scenery. They were in favor of the >>Anschlub<< idea – which the Imperial Family strictly opposed. Furthermore, their socialist attitude stood against the conservative of the Habsburgs. They actively worked against the Imperial Family throughout the whole war. The Communists were another group opposing the Imperial Family for ideological reasons. Although the principles of monarchism and communism strictly oppose each other, they worked together sometimes, as both camps – or at least certain representatives – realized that they were fighting the same enemy and therefore agreed to an ‘armistice’ for the time being. But nevertheless conflicts did arise as many aims of the supporter of all Communist resistance, the Soviet Union, differed greatly from the Legitimists intervention. Naturally the Stalin Regime worked actively against the Legitimist resistance. The alliance with Stalin after 1941 did also hamper the relations between the Western powers and the Habsburgs as Britain and the United States did not dare to challenge the pact with the Soviets. Many members of the republican resistance saw the danger of a restoration of monarchy in the support for Hapsburg. The Imperial Family had indeed never clarified for which ‘Austria’ and for ‘which Hungary’ they were campaigning. The borders which were drawn in 1918/1919 caused much disagreement, dispute and fury, especially in Austria and Hungary, as these countries had to hand over vas areas to the newly created states. The House of Habsburg did not accept these changes on Europe’s map, either, and, further more, wee naturally by no means opposing a shift towards monarchy, which, they thought, could happen through a plebiscite (28). However, the restoration was not the condition for their work (13). Nevertheless, the Habsburg’s omission to state clearly the definite areas which concerned them in their agitation within the Austrian and Hungarian resistance as well as the attempts to re-create a larger geo-political unity within the Danube area irritated not only many Austrian Resistance politicians. This leads directly to another group of fierce animosity towards Archduke Otto and his confidants: the nationalists from many of those states which succeeded the Austro-Hungarian Empire, most of all Edvard Bebes. The Socialist Benes saw the national sovereignty of Czechoslovakia severely endangered by the activities of the family of their former rulers. An attitude which is understandable from Benes’s point of view, being one of those who deposed the monarchy in Bohemia, Moravia and Slovakia and formed the Czech Republic. Another, quite different reservoir of rejection of the Habsburg engagement, as mentioned earlier in the essay, came from British and American officials for which three main reasons can be given. First of all, Western governments were concerned about possible – and indeed activated – resistance from the governments-in-exile of those occupied countries that had been parts of the old Danube Monarchy, another reason was (after 1941) the concern not to annoy the Soviets who naturally opposed the ‘reactionary’ Legitimist movement. Lastly, personal reasons should not be left out, either. Certain British and American politicians, among those Anthony Eden, showed feelings of hatred against the Habsburgs because of their Roman Catholic religion and out of historical enmity against the former opponent Austria-Hungary. According to Anthony Eden a separated Austria had always caused harassment in its political relations to Germany. Though that analysis of the work of the Hapsburg Family I have come to the conclusion that the claim that the Imperial Family only worked for the restoration of their former power as a necessity for their activities is evidently not true. On the other hand, I should not support the thesis that their work was ‘most significant and nobody else contribute so much’ (10) as it is almost impossible in history to pose such cardinal statements. However, I have gained the opinion that the Habsburgs were indeed important characters within the Austrian resistance movement against Hitler, and their work was certainly of great historical importance, as well as the work of other groups and thus contributed much to the outcome of the Moscow Declaration which declared Austria a victim of Nazi Germany’s aggression and therefore had to be freed. Footnotes 1)

Enc. Britannica, page 520 |

||

|

zutragen".26) however the Frenchmen the allied decisions to anticipate there did not want to still wait, muf3ten the Osterreicher. Only as the existence of osterreichischer battalions in Yugoslavia, lie8 France - already under de Gaulle - was become known its Zuruckhaltung falls to and gave in the middle of April 1945 the list of a osterreichischen militarischen unit bekannt.z ') as tie point of this battalion applied the city Riom in the section Puy de Dome. The instruction went by, a first Detachement of 200 freiwilligen and four") off izieren ehemoglichst in march to set. After the report of Hans's realm man the message was taken up by the list of osterreichischer units in the camp Suzzoni, with rough Freude°; all Lagerangeh6rigen announced itself without exception as freiwillige. Since the exact end of the war was not to be counted yet to foresee and on the list of further battalions, one gave for the time being the priority to the jungsten Jahrgangen. On 2 May 1945 the first battalion in AI sailed itself under Filhrung of realm man ..... greed an and came on 12 May into Riom to 29) it with 6sterreichischen freiwilligen from other camps into France on the effective-strong of 508 men erganzt and remained full four months there in training. As 1. Osterreichi battalionbattalion battalion, consisting of three Schiltzenkompanien and of a staff company, formed it a selbstandigen, organizational for the franzosischen army subordinated federation. This was set on 14 September 1945 in march, reached end of the monthly Innsbruck, where the Hochstkommandierende of the franz6sischen zone of occupation removed general Bethouart in bsterreich, on 10 October the Defilierung of the battalion before the yard castle. In the consequence the battalion, whose companies were befehligt by Osterreichern, provided the border service in Vorarlberg together with franzosischen units. But plotzlich and unexpectedly joined the inter+allied advice on 14 December 1945 the Auflosung of the federation much to the Enttauschung of the freiwilligen, who hoped, this battalion became once the core stick of the army of the free and selbstandigen bsterreich bilden.ó) the end of war prevented the list of further osterreichischer battalions. Remaining in the Camp the Suzzoni Zuruckgebliebenen, which likewise still on the employment in unitunit units had counted, to at the beginning of of 1946 in its North African camp and divided here as well as after their transfer after Sudfrankreich the fate of other Wehrmachtsangeh6riger than Kriegsgefangene.3 ') United States protecting it in Grof3britannien 1ê succeeded to uberzeugen politician of the necessity for its own osterreichischen combat force were located in the United States politician, everything in front the Prasident of the union, to their once gefaf3ten plan of the infantry battalion No. 101, which as the first step was meant toward acknowledgment of a osterreichischen government-in-exile and, as is shown, also by the opponents of this battalion one interpreted in such a way. Roosevelt was the author and within the American administration the most decided advocate of this osterreichischen troop. Fur it had this federation of approximately 900 men a purely symbolic character, like this also with ahnlichen Auslanderformationen (Greece, Norway, the Philippines) the case was; the militarische value stood fur for the Prasidenten, which had been satisfied already with a company, thus about 120 men, hardly to the Dgbatte. Roosevelt kept Osterreichi battalion in the question despite serious doubts from that was department and on the part of a parliamentary group from the State department around the Assistant Secretary OF State Adolf A. Berle Jr. the upper hand. Contrary to the latter the Secretary OF sat down was Henry L Stimson after some time of varying, also against the Unwillen of high Militars, fiir to the Truppenkorper occupied with Osterreichern in. Stimson was it also, that on 19 November 26) realm man, a.a.0., P. 77. 27) red woman red book. Representations, documents and of proofs to the prehistory and history of the Okkupation Osterreichs (after official Ouellen), Vienna 1946, P. 166 f. CPU) realm man, a.a.0., P. 78, speaks of fiinf officers. 29) realm man, a.a.0., P. 78 FF. 30) DOW 3833; DOW 337; Felix Kreissler, the Osterreicher and its nation. A Lernproze8 with obstacles, vienna Koln Graz 1984, P. 280. 3') Palisek, a.a.0., P. 210 f.

Hans's realm man, Angehdriger of the franzosischen army, with wife in Algiers, autumn 1944.

Ernst Haeusserman in the uniform of the American Streitkrafte. Company of the 1. Osterreichi Freiwiiligen battalion, Riom (France). rikanischer connecting with 6sterreichischen freiwilligen planned, which should have the same rights as soldier other federation. In the training stage the officers American Burger osterreichischer descent warden its, until then at present the employment Osterreicher themselves could take dTese positions. Enough-end if freiwillige should not to be found, one thought of the transfer iisterreichischerEmigranten from other units. The soldiers warden the oath on the United States carry out, American army uniforms carry possibly fur the American StaatsbOrgerschaft for and qualify. The battalion was not meant as combat and as an occupation troop. As planned, the training of the bsterreichischen battalion began on 15 December 1942 in the Camp Atterbury, Indiana. When became obvious, daf3 with freiwilligen alone the battalion do not aufzufullen were, American Staatsburger osterreichischer origin and 6ster reichische emigrants from other units in the Osterreichi battalion were shifted - official with agreement of the concerning, but in many traps also against their will. Few that altogether 588 soldiers (conditions center Marz 1943) were Angehorige of the succession states - among other things 30 Tschechoslowaken, 27 Poland, 21 Yugoslavs, 19 Hungary -, and according to report of the commander of battalion lieutenant colonel Vincent J. Conrad grassierten discontent and of resentment under the Nationalitaten. Soldiers regarded the battalion as Vehikelfur the reputting of the Habsburgerherrschaft in Europe ("I don't want ton fight for petrols. I want ton fight for America." fur petrol does not want to kampfen. I want fur America combat EN")"), befurchteten by the transfer a Verzogerung of their Ansuchens around the Staatsburgerschaft or was simply to have been verargert, from their fruheren militarischen federation have been pulled out. Due to thereupon breaking loose protest waiter the obligation transfer granted to Stimson in the Marz 1943 the jerk transfer all that one, insisted on on which in the main the Volontare Obrigblieben beginning of April 1943 was do material this 144 men. The intended battalion-strong from 931 soldiers to to reach, seemed with the available recruiting speed only in two and a half years verwirklichbar3 '), on which the boss of the general staff in the middle of suggested April 1943 picking up. Roosevelt gave its consent, to and at the beginning of of May 1943 were issued the order, the battalion as fast as moglich and without 6ffentliche Ankundigung to eliminieren35). Goldner registered serious errors and Fehleinschatzungen on sides of the administration as well as the recruiting committee, which were the focus of all attacks. Neither it, the American Offentlichkeit and the 6sterreichischen emigrant of a clear separation, here bsterreich battalion and there having castle aspirations succeeded to the American administration nor the representatives of the recruiting committee to uberzeugen. The?Free Austria Youth Committee ", which was close to Ferdinand Czernin, printed its Mif3 approval clearly out: "... incoming goods feel convinced that you acres struggling for the interests OF your family and emergency for the liberation OF Austria. ... You of acres disturbing the unity which incoming goods need badly into the struggle against in such a way the Axis powers." (?... we are uberzeugt, do not daft you fur the interest of your family argue and not fur release bsterreichs. ... They storen the unit, we the straight now in the war against the axle-made so urgently brauchen.")'6) it became hardly on positive and negative experiences with battalions of this kind already existing zuruckgegriffen; the Offentlichkeitsarbeit did not exist as well as, the Ankundigung waiter the list of the battalion and of a recruiting committee came so plotzlich, as if one wolite all uberrumpeln and before completed facts placed. Too strongly on Roosevelt one set, then daft one believed, without further Aufklarungs&beit do to konnen. Heavily weighing questions, how those that in the case of the capture of the battalion on geh6rigen by the third realm ge schehen warde - capture as Hochverrater - and as one secures oneself before it kñnte, not enough were considered. Just as little one took Rilcksicht on the desire of many 6ster of reichischer emigrants into the egg nigten states, which regarded the acquisition of the American Staatsburgerschaft fur more importantly, than the Wiederge winnung the Unabhangigkeit of the Heimatstaates".3 often not remained in best memory ') to Jugoslawien38) than filnf the bsterreichischen battalions were trained and/or one were used, were the power situation on the Balkans and also in the operational area in Slovenia already for the disadvantage of crew power decided. Already since the surrender of Italy in September 1943 and the area controlled before by Italy saw themselves forced to armed forces and police troops, grof3raumige Umfassungsmanover and operations in favor of punctual employment and of control of Stutzpunkten as well as of connecting lines zuruckzustellen; also at that time verstarkt the allied Unterstutzung at the same time began fur Tito. At the end of of 1944, as the training of the 1. Osterreichi battalion to the off schluB, was also the area came around Crnomelj and the Suha Krajina already Nebenschauplatz of the German Parti sanenbekampfung. In Crnomelj the main staff of the people release army and of the partisan department Sloweni was appropriate ens for and not far of it - in Tribuce - the A6sbildungslager of the 1. Batail lons. The periphery Crnomeljs formed its area of operations, insbesonde RH the protection from small mobile raiding parties of the crew closes and at the same time the safety device of the basis to the north, whereby the Krka between Zuzemberk and Novo Mesto uberschritten only rarely became. Two act existence are this Darstel (continuation on P. 534) 33) PM, 24. M5rz 1943. 34) Erhart, a.a.0., P. 432. 35) Erhart, P. 274, 433 to 436. 36) at open type character, 28 December 1942, Erhart, a.a.0., P. 429. 37) Goldner, a.a.0., P. 170. 38) Holzer, November I POJ, P. 411; ders., the 6ster of reichischen battalions in Yugoslavia 1944 to 1945. To the resistance strategy of the 6ster reichischen communist emigration, in: Contemporary history, 4. Jg., number 2, November 1976, P. 39-55; Red woman red book, P. 145 f.

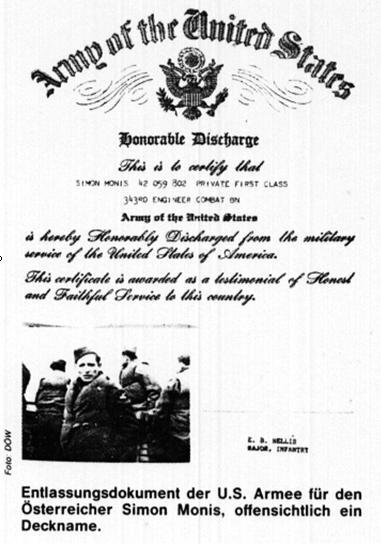

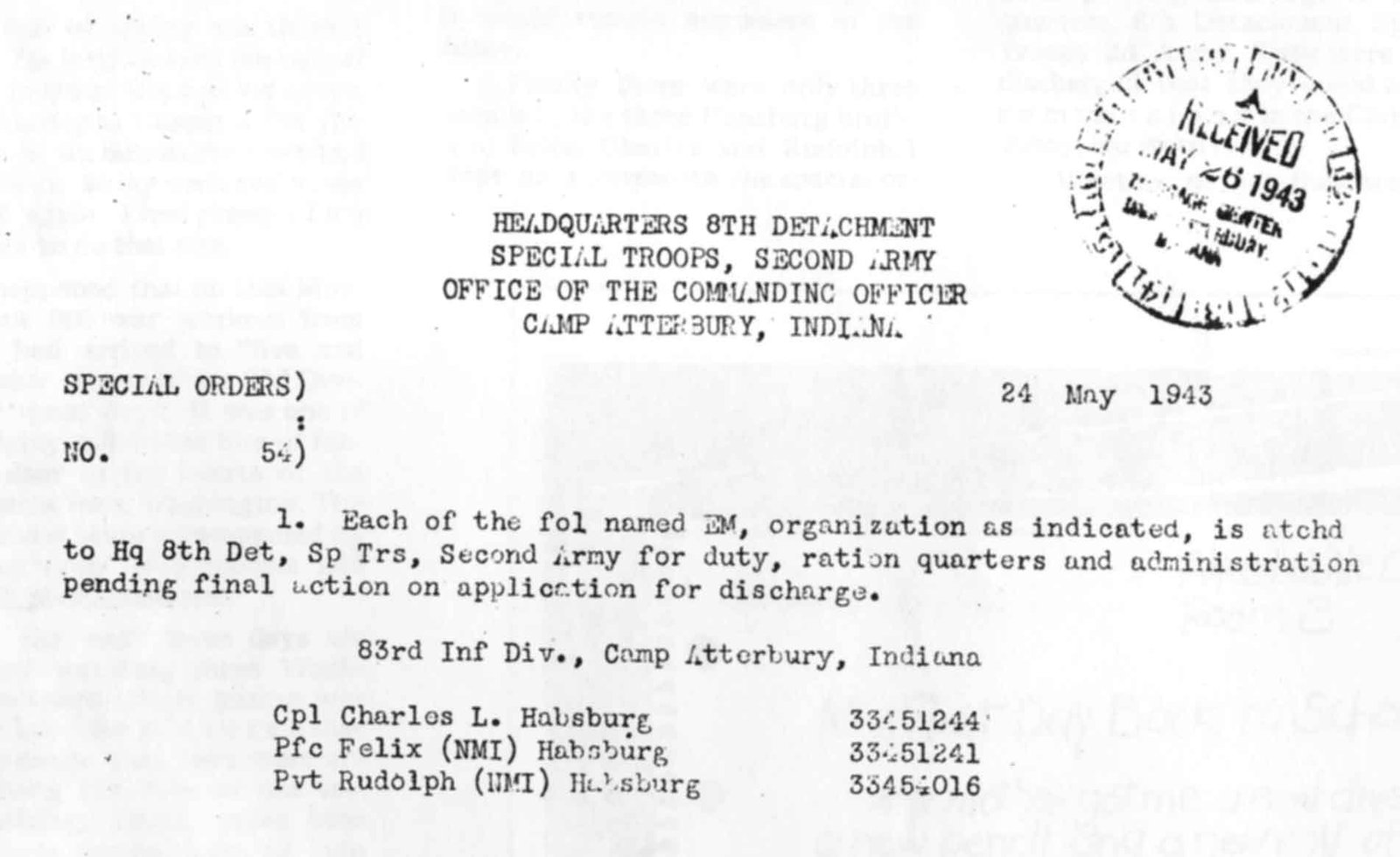

Dismissal document of the U.S. army |

||

|

Felix von Habsburg HAVING CASTLE - LORRAINE [ imperially family ] { FELIX - Lineage OF Karl I } FELIX of Austria [ having castle Lorraine ] { Felix Friedrich August Maria of

victories the Franz Joseph Peter Karl Anton Robert petrol Pius Michael

Benedikt Sebastian Ignatius Marcus d'Aviano of having castle Lorraine } Enfants/Children/children MARIA del PILAR of Austria [ having castle Lorraine ] { Maria del Pilar Sophie Valerie

Charlotte Zita Johanna Marcus d'Aviano Caspara of having castle Lorraine } D.P. " POSCHINGER CARL PHILIPP of Austria [ having castle Lorraine ] { Carl Philipp Maria Otto Lukas Markus

d'Aviano Melchior of having castle Lorraine } KINGA BARBARA of Austria [ having

castle Lorraine ]

RAIMUND (Ramón) of Austria [ having

castle Lorraine ] MYRIAM of Austria [ having castle

Lorraine ]

ISTVÁN of Austria [ having castle

Lorraine ] VIRIDIS of Austria [ having castle

Lorraine ] |

||

|

42 Nerkunft and

layeri refrained from the author - the following are erwahnt: Charles of Ripper, petrol pointed, Friedl Firnberg and Franz Honner. As example of this calling Charles R. von Ripper is emphasized. Rudolf Charles of Ripper came of to a noble bsterr. Officer family (Colonel Carl 19,12,1860, Julius 22,3,84, admiral) turned - like many bsterr. Aristokraten - that linking to and became in the Spanish BUrgerkrieg 1936 officer of the rep. Air Force. it fled 1939 into the USA and occurred 1941 C as Capitain into the OSS of the USA. He had been spent already 1933 in Berlin by the Nazis in the KZL, jeJoch became he by the intervention of the 6sterr. Ambassador releases. It was several times wounded as a specialist against Japan, in North Africa, inserted in pre that Asia, at the Balkans and into Italy and. 1944 it became as a OSS liaison officer 4. Operation zone Titos sent, separated as a major from the US Streitkraften. Beis iel mehrfachen

a11.Militdrdienstes d. Osterreicher Note: the above table is presented exactly as the software translated it. I cannot make heads or tails of it and it is probably not in the format it should be. If anyone can understand the information, I would appreciate hearing from you. |

||

|

Otto von Habsburg |

||

|

Born in Reichenau Lower Austria on November

20 1912 son of Archduke Charles The Emperor Frantz Josef I died on November 2lst 1916. 29-year-old Archduke Charles (Otto von Habsburg's father) succeeded him becoming Emperor Charles I of Austria and King Charles IV of Hungary. The last coronation of a Hungarian King took place on December 30th 1916 in the church of the Blessed Virgin in Buda Castle. This was the last time the Hungarian nobility and clergy could be seen in their full pomp. The ceremonial dress worn by the Queen Zita (Otto's mother) and the young crown prince Otto was designed by the great historical painter - Gyula Benczur. The death of Emperor Charles in 1922 one of the most likeable of the Habsburg rulers brought the 800-year-old rule of the dynasty to an end. After the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy Charles and his family were exiled from Austria in 1919 by a special law and all their property was confiscated. (The right to return to Austria was granted only in 1966 by a decision of the Administrative Supreme Court). After leaving Austria in March 1919; the family lived in Switzerland till the end of 1921 and on Madeira (Portugal) until =1922 - where Emperor Charles died on April 1st 1922. Until 1929 the family lived in Lequeitio, Spain. On November 20th 1930 Otto von Habsburg celebrated his eighteenth birthday which meant that he had come of age and could inherit the titles of his late father. This event was celebrated in the Habsburgs' private chapel when Queen Zita read out a declaration to the effect that in accordance with the laws of the house of Habsburg and with the will of her late husband she ceased to bee the legal guardian of her son Otto. Following this Otto was hailed as Emperor and King as well as head of the whole house of Habsburg-Lotharing. Until 1939 in Steenockerzeel, Belgium. In 1939 the family lived in Paris. From 1933 onwards he fought against National Socialism which led the Nazis to issue a war-rant for his arrest after they had occupied Austria in March l 938. Since 1936 member of the Pan-european Union its representative in Washington from 1940 till 1944. 1944 to l954 mainly in France except for a few months in Austria in l945. From 1942 he worked actively to prevent the planned expulsion of Germans from the Eastern territories. During World War II Otto von Habsburg used his connections in Spain and Portugal to save some 50 000 European Jews from the clutches of the Nazis. Since l954 he has lived in Pöcking Bavaria. In 1951 he married Regina Princess of Sachsen-Méiningen. The engagement ceremony took place in the Bavarian town of Possenhofen in the house where many years before Emperor Franz Josef 1 was engaged to his beautiful Wittelsb a great inspiration Otto von Habsburg was to them. He has never lost contact with Hungary and he always followed Hungarian affairs with great interest. When he was asked who he had learnt to speak Hungarian he replied that Hungarian was in fact "one of his mother tongues" since at home he had always spoken Hungarian. Since 1957 Vice-President of the Paneuropean Union and af1Coudenhove-Kalergi in l973 its President. Since June l979 European Parliament elected for Bavaria on the list of the CSU reelected in 1984 and 1989.amation League' Medal of Europe of the Free State of Bavaria 1991 etc. |

||

|