|

Chapter 2

CAMP ATTERBURY

Compiled by

MAY E. ARBUCKLE

Bartholomew County Historical Society

PREFACE

If in this story I can

convey to the reader something of the magnitude of the task of the Federal

Government in selecting the site, acquiring the land, and building Camp

Atterbury in the short period of time in which it was accomplished, I

shall think the time spent on it was not wasted. I should like also to

leave the thought of the hard training, broken by all pleasurable

diversions possible, but nevertheless each boy knowing why he was being

trained, and of the tough fiber ingrained in the American character that

made it possible for him to "take it." I wish I could have drawn a veil

over the battlefields abroad and the suffering of the wounded returned to

Wakeman hospital. When will we learn that nothing is gained by war? If we

can accomplish the impossible, materially, why can we not find a way to

keep peace? I, who write of war, believe in peace, and that it is not

impossible if the world would put forth an equal effort in that direction.

I want to acknowledge the great help I have had from the pages of the

Columbus Evening Republican, its former editor, Melvin Lostutter, its

present editor, Robert Gordon, and Staff Writer Robert Marshall, who also

read the manuscript. Acknowledgment is also made to the public relations

officer at Camp Atterbury, Capt. John E. Wilson, for helpful suggestions

and material; to the post signal office at Camp Atterbury for negatives of

pictures; to John

V. Sellers, editor of the Franklin Star; to Col. B. C. Dunn, division

engineer of Fifth Corps Area Headquarters at Columbus, Ohio; and to my

neighbor, Joseph W. Springer, the chief negotiator for acquisition of the

land, and to his sons, W. E. Springer and R. H. Springer, who accompanied

me to Atterbury at different times, assisting me there.

The Historical Bureau staff has been able to add some material regarding

administration and training from the official records of the camp now

deposited at the Kansas City Army Records Center.

I have relied very heavily on the Camp Crier, the Atterbury newspaper, for

camp activities. The newspaper clippings in the Columbus Public Library

and in the Bartholomew County Historical Society Museum have been helpful

in following the story of the camp.

Finally, I must add an extra word of thanks to Robert Marshall, who has

been most kind and helpful.

ELIZABETHTOWN, INDIANA MAY E. ARBUCKLE.

LAND SURVEY AND

ACQUISITION

In January of 1941 orders were issued

by the War Department to the Fifth Zone constructing quartermaster of the

Army, who at that time was in charge of all land acquisition for military

purposes in the states of Ohio, Indiana, Kentucky, and West Virginia, to

investigate potential sites for a new Army camp in the State of Indiana.

An investigation of various areas under consideration was made by Charles

H. Hurd, architect-engineer of Indianapolis, and U. S. Army personnel, and

recommendations submitted to a board of officers selected from Fifth Corps

Area Headquarters. This board, after investigating the proposed sites,

selected one in south central Indiana, including land in northwestern

Bartholomew County, and extending north into Johnson County, and west into

Brown County, as the most desirable. It was largely a rural area, yet it

was close to urban centers. Part of the land was sub-marginal; it was

partly hilly and partly level. U. S. Highway 31 and the Pennsylvania

Railroad offered easy access to the outside world.

The first official word of the new camp came in a dispatch from Washington

on April 28, 1941, which said that a cantonment for 30,000 men would be

established outside Columbus, the county seat of Bartholomew County, if

the size of the Army was increased. This confirmed the rumors that had

been afloat in the community since the appearance of the government

engineers early in the year.

On May 10, 1941, the Quartermaster General issued instructions to the

Fifth Zone constructing quartermaster to make preliminary plans for the

acquisition of some 50,000 acres of land. The Charles Hurd Engineering

Company was given the job of making the survey for the Army and set up

headquarters in the Columbus armory. The work continued throughout the

summer and fall. Some two hundred men were in the field with a

proportionate number in the survey office.

Edwin Hurd, who was in charge of the survey, stated that the tangles of

vegetation encountered in parts of western Bartholomew County were as

tight as those which his men had encountered in making similar surveys in

the tropical jungles. At times it was necessary for four axmen to go ahead

of the instruments to dear the way for the lines. There were many snakes

in the hills, including rattlers and copperheads. The U. S. Public Health

Service gave all the field men "shots" to protect them from snake bite.

Poison ivy was another hazard. (Note: See the HURD REPORT, elsewhere on

this web site)

Appraisals of the tracts of land began June 19, 1941, with those in

Johnson County. D. R. Martindill, of the Soil Conservation Office at

Dayton, Ohio, was assigned to the project at the request of the

Quartermaster General in Washington. Mr. Martindill requested L. J. Hoing

of the Federal Land Bank in Louisville to detail appraisers to work on the

project.

Abstracts of tide to the land were prepared by the Columbus Abstract

Company. In four months time they did as much work as in an average

four-year period. The last of the certificates of title were delivered to

the Federal Government on November 1, 1941.

All of this was before the war started; the people were naturally

disturbed and fearful at the prospect of leaving their farms and their

homes. It was expected that some 700 families would be affected. Some of

these were living on land that had been handed down in their family since

it was purchased from the Federal Government in the 1820's and 1830's. The

uprooting of a community of this size was certain to bring hardships and

heartaches to many. Others, that would not be affected by the land

transfer, were apprehensive of the coming of soldiers in great numbers

into the community. The project blew hot and cold for eight months.

Then came the attack on Pearl Harbor. Overnight, the possibility of the

Army camp became a reality. But with the coming of war, the attitude of

the community changed; the need for the camp was obvious; everyone was

willing to make sacrifices for the national good. The people waited for

the official word that would trans-form their quiet agricultural community

into an area teeming with wartime activity. It was not long in coming. On

January 6 the Columbus Evening Republican received a telephone call from

Congressman Earl Wilson saying the camp was definitely to be built. A week

later a directive was issued by the Secretary of War to the Chief of

Engineers to acquire 52,730 acres of land in Bartholomew, Johnson, and

Brown counties, Indiana, for a cantonment and a training site. This was

later reduced to approximately 40,350 acres, consisting of some 643

individual tracts.

The directive was passed on to Col. C. L. Hall of the Ohio River Division,

who in turn delegated the supervision of the construction of the camp to

Col. Henry Hutchings, Jr., district engineer at Louisville. Capt. W. S.

Arrasmith, a former Louisville architect, was placed in immediate charge

and set up headquarters in February, 1942, on the site of the camp. The

Army did not wait until all the formal procedures connected with the

transfer of the land were concluded before beginning construction. Time

was too precious. The first construction was begun in a cornfield during a

February snowstorm.

The groundwork for the transfer of the land had been laid the year before.

The surveys of individual tracts with their appraised value and an

abstract of title were in the hands of the War Department. Everything was

in readiness to begin negotiations with the land owners. Joseph W.

Springer, of Elizabethtown, was appointed supervisor on January 14, 1942,

to handle these negotiations.

He had been serving as secretary of

the Production Credit Association, a branch of the Farm Credit

Association, with offices at Seymour. He was well known in the community

and acquainted with local land values. A number of other negotiators were

appointed to assist him in the work.

The usual procedure would have been for the government to approach the

owners and obtain what land they could before filing condemnation

proceedings, but in order to expedite matters a condemnation suit was

filed in the Federal District Court in Indianapolis on January 24, 1942,

covering 7,271 acres of the total area. Immediate possession was asked and

obtained for 2,500 acres in the cantonment area where construction was to

begin. Occupants of this area were asked to vacate by February 14, while

those in the remainder of the condemned area were to have until March 24.

All but 800 acres of this first land to be taken was in Johnson County.

Negotiations with the owners followed filing of the suit. Those who

accepted the government price signed an option. This was sent on to the

War Department and, if accepted, the owner was sent a purchase agreement.

The abstract was then brought up to date and final papers signed. Lawyers

Ralph Fraker, of Columbus, Carlton Shuck, of Franklin, and John Wright, of

Nashville, were appointed to handle the final transfers. The first check

for land was received by Mrs. Louisa Prichard on March 6, five weeks after

she had signed her option.

The prices offered by the government were lower than the inflated prices

being asked for farms listed for sale on the open market; they were lower

than the owners had expected. Some did not sign options and thus became

defendants in the condemnation suit, hoping by this procedure to receive

more than the amount first offered. On April 4 the government filed a

"declaration of taking" in the Federal court, whereby the title to the

remainder of the 7,271 acres was transferred to them pending outcome of

the suit. This was to permit work on the site to continue. Commissioners

were appointed by the Federal court to review the price offered for each

tract and dates were set for hearings. At these, the appraisals of the

Land Department and the court would be offered as evidence, and the owner

could present witnesses to prove that it was worth more than the

government was offering. A jury or the Federal judge would then decide the

price that should be paid. The War Department deposited money with the

clerk of the court and the landowners were allowed to draw a part of this

while waiting for the outcome of the suit.

It was a year before all the suits involving the land were settled. As a

rule, the prices decided on by the jury were much closer to the government

valuation than to that of the owner.

As the winter and spring went by, the boundaries of the camp area were

being constantly changed. On one day a man might find his farm included,

and the next day it would be outside. Many didn't know whether or not to

plant their spring crops. By March the total area had been whittled down

to about 37,000 acres, and negotiations were begun for the 30,000 not

included in the first condemnation proceedings. Here, the normal procedure

was followed of trying to obtain options on the land prior to the filing

of a condemnation suit. Negotiations continued throughout April before

filing of condemnation proceedings on April 30. All of the people in this

area had to be out of their homes by July 1; in certain districts they had

to be out by June 1.

One of the big problems connected with the acquisition of the land by the

War Department was the paying of delinquent taxes and mortgages.

Delinquent taxes in Nineveh and Union townships of Bartholomew County

totaled $ 18,834.56. Persons living in the camp area had school fund and

cemetery loans totaling some $45,000. By the time these loans were paid,

some of the owners did not have much left.

In October, 1942, it was announced that 3,600 more acres were to be added

to the camp area. Practically all of this was in Brown County and was

sparsely settled. It had been included in the original survey. The

government took possession of the land on December 1 by condemnation

proceedings and the residents were given fifteen days in which to vacate.

As finally settled, the camp acreage totaled 40,351.5348 acres of which

10,398.22 acres were in Johnson County, 25,908.221 in Bartholomew County,

and 4,045.0938 in Brown County. Approximately $3,800,000 was paid by the

government for the land, an average of $94 per acre. In Bartholomew

County, all of Nineveh Township except 940 acres was included; 325 acres

were taken in German Township; the area that remained in these two

townships was merged into one. Union Township had only 4,000 acres left

but it managed to maintain its township unit until November, 1946, when

property owners petitioned that it be divided and half added to Columbus

Township and the other half to German Township. Harrison Township lost

1,235 acres. Bartholomew County lost $990,000 from its assessed valuation.

The area included parts of Blue River and Nineveh townships in Johnson

County, and in Brown County it took in parts of Hamblin and Washington

townships. The length of the camp area at its longest north-south point is

12½ miles; the width is 8 miles at its widest east-west point. The effort

made to avoid splitting farms resulted in a boundary very irregular in

places.

Of the 643 tracts of land included, 402 were acquired by direct purchase

from the owners. The remaining tracts were acquired by condemnation

proceedings, either because of defective land titles or inability of the

land owners and the government to agree on the price. Federal officials

reported that this percentage was about the same as in other localities

where land was being taken by the government.

There was much sadness in finding new homes and severing old ties. Oscar

Snepp was the first to buy a new farm. He bought in the southwestern part

of Johnson County, but before he could move, this site was taken in the

camp area so he had to buy still another farm. The only town in the area

was Kansas, with a population of thirteen. One of its inhabitants, Val

Ulrey, was eighty-five years old. He had started his blacksmith shop there

in 1878. But Val Ulrey did not have to move. Death came to him on May 2.

The majority of those purchasing new farms bought in their home county or

as near to it as possible. Farmers who needed financial assistance in

obtaining new farms, while waiting for payments from the government for

their old ones, were urged to turn to the offices of the Farm Security

Administration.

There were 15 cemeteries in the camp area containing some 1,500

graves. Five were in Johnson County: the Pisgah Methodist Cemetery, the

Harriett Creek Cemetery northwest of the Pisgah Christian Church, the

Knapp Cemetery on Road 252, and two family burial grounds. Two

Revolutionary soldiers were buried in the Pisgah Methodist Cemetery:

Matthias Parr, a New Jersey private, and John Poe, of North Carolina.

Cemeteries in Bartholomew County included three in Union Township: St.

John's Lutheran, Bethel Methodist, and Ohio Ridge; three in Nineveh

Township: Kansas Methodist, Garrison, and Long; and two in Harrison

Township: Mt. Olive and Mt. Carmel. Bodies in the Kansas Methodist

Cemetery and in one of the private cemeteries in Johnson County were not

disturbed. Those in the other cemeteries were removed to a new cemetery

laid out by the government on the Nate Wells farm, two miles north-west of

Edinburg and one-half mile west of Road 31. The arrangement of the bodies

in the old cemeteries was preserved in the new one. It was necessary to

acquire new burial vaults for each body. Contract for removal and

reinterment of the bodies was given to the Wearly Monument Company of

Muncie. Two cemeteries in Brown County, the Christian Bethel Church

Cemetery and a private one, were not disturbed.

The camp closed five schools in Bartholomew County: the Kansas, Records,

and Renner schools in Nineveh Township; Precinct and Lowell in Union

Township. At the Records school on the Mauxferry Road, the enrollment

dwindled day by day as the families moved away. The teacher, Miss Alta

Harrell, had earlier lost her school near Madison when it was swallowed by

the Jefferson Proving Ground. Out of an enrollment of twenty-nine at the

beginning of the term, only a few were left when the school closed on May

5. The Renner school was not in the camp area, but the homes of most of

the pupils were. Only a few pupils were left after the evacuation.

Most of the farm homes in the cantonment area were torn down at once; a

few were taken over for a short period by construction company officials

and engineers for offices, a few others were reserved for camp stables

and the motor pool. In razing the buildings, many interesting things came

to light. Two of the barns had originally been log cabins and one house

was found to have been built around a one-room log cabin.

By June 19, eleven days before the

deadline for evacuation, almost all the inhabitants of the 30,000-acre

tract had moved. A Columbus reporter, roaming the area, found only scenes

of desolation: empty houses surrounded by high grass and weeds; gates

standing ajar, empty barns and chicken houses, without a dog or chicken

left to break the silence. War had come home to Indiana.

CONSTRUCTION

At the same time that negotiations for

the land were going for-ward, construction plans were also being pushed.

The first contract in connection with the camp was let on January 30,

1942, to the Calumet Paving Company, of Indianapolis, for construction of

an 8-mile railroad spur into the camp area from the

Indianapolis-Louisville branch of the Pennsylvania Railroad. The railroad

company had already started work on a switch and 125-car siding near

Amity.

Bids for grading and for construction of buildings and other facilities at

the camp were opened February 6 in the Federal court-room in Louisville.

Approximately 1,700 buildings were to be built. Contractors could bid for

the whole job or for one or more of the smaller units into which the

contract was divided. These units were roughly:

A-1. 619 temporary buildings to house one Army division. These included

242 barracks, each with accommodations for 74 men, 97 mess halls,

recreation buildings, theaters, a sports arena, headquarters buildings,

storehouses, infirmaries, chapels, officers' quarters, etc.

A-2. 550 temporary buildings for troops of auxiliary units attached to the

division. These likewise included barracks, mess halls, administration

buildings, infirmaries, post exchanges, etc.

A-3. 102 temporary buildings for hospital group. These were to be of

concrete block construction.

A-4. Utility buildings including warehouses, ordnance and repair shops,

quartermaster offices, bakery, laundry, fire stations, incinerators, cold

storage buildings, steel igloos to hold ammunition, salvage yards,

prisoners' barracks, etc.

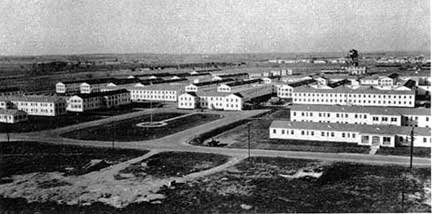

(Barracks under construction)

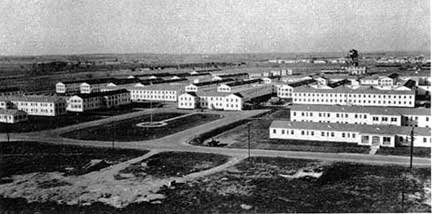

(Wakeman General Hospital under construction)

B. Roads, drainage,

grading and water distribution

C. Railroad construction

D. Electrical distribution system

E. Water supply and sewage treatment plants

The Caldwell-Wingate Company of New York City was the only firm that

submitted a general bid for the entire job. Their figure was a little over

$34,500,000 and was rejected. Bids for the A-1 and A-2 groups were so high

that the War Department decided to further subdivide each of these into

four smaller units and readvertise for bids. The total of the new bids,

opened in March, was smaller than the original ones. In the end, total

construction costs were close to $35,000,000, but this included some

buildings and other work not in the original specifications.

Contracts in the A-1-4 units were awarded to the following firms: A. W.

Kutsche, Detroit; the Thompson Construction Company and the H. L. Fisher

Corporation, Albany, New York; the A. Farnell Blair Company, Decatur,

Georgia; the Consolidated Construction Company of Chicago; and O'Driscoll

and Grove, Inc., New York City. The Blair company built three-fourths of

the bar-racks buildings. Subcontractors under the Blair firm included the

Meyer Plumbing and Heating Company, Marine Electric Company, Theobald

Electric Company, and Diecks Electric Company, all of Louisville; Thomas

J. Sheehan, St. Louis, plumbing; S. E. Roofing and Metal Company, Atlanta,

Georgia, and Walker-Jamar Company, Chicago, who installed the heating. The

sports arena built by the Blair Company was 133 x 181 feet with suspension

roof.

The Pontarelli & Son Company and the Rock Road Company, Chicago, received

the contract for Unit B, covering roads, drainage, gradings, etc. The

grading work was sublet to Seward-McDougal-Lain. The latter arranged to

light the area so that work could be carried on through the night.

C. A. Hooper & Company, Madison, Wisconsin, and the Monroe Electric

Company, Chicago, received contracts for Unit D, the electrical

distribution system.

The contract for sewage disposal and water supply, Unit E, went to the

Birmingham Construction Company, Birmingham, Michigan. After testing the

wells in the camp area, the State Board of Health closed over half of

them. The construction companies drilled wells for temporary use in their

own work. The permanent water supply system included wells and a

reservoir; the wells were outside the camp area and the water was piped in

under Highway 31. The Harry Fox Company of Shelbyville had a subcontract

for the well drilling.

Following the letting of the contracts, officials of the construction

companies began to arrive on the scene. Some of them established offices

in the houses vacated by the farmers. Transient workers began to drift

into the area, but not many were needed at first. The preliminary work of

grading, excavating, and laying of foundations had to be done before

construction could get into high gear. The weather was unusually bad

during the early months of 1942. First it would snow and freeze, then the

ground would thaw and it would begin raining. The area became one mass of

mud. This freezing and thawing process continued up into May and rains

continued to slow down progress all during the summer. When the ground

dried off the workers had to contend with the dust. Delay in getting

materials also held up the work.

The Hurd Engineering Company, of Indianapolis, which had handled the

earlier surveys of the region, had a staff of 200 men busy in their

Franklin office and on the grounds adapting Army specifications to the

local situation. The location of buildings and streets was mapped out and

stakes set. Shortages in materials often necessitated a change in the

plans.

By the first of May the number of men working on the camp had reached

8,000. On June 16, the peak employment was reached with 14,491 on the

payroll. These men came from many different parts of the country. Some had

worked for these same construction companies at other Army camps or on

other big jobs. Many were from towns in Indiana. At least a third of them

brought their families with them. Edinburg, the town nearest to the

construction area, was the first to feel the impact of the rush. Its

population of 2,466 reached 4,000 by April. Every available room was

taken. Even the John Talbert burial monument establishment was converted

into a 10-bed dormitory. Later arrivals sought homes in the surrounding

area, in Columbus, Franklin, and the small towns nearby. Trailer camps

already in existence filled up and new ones were established. Summer camps

along White River and its tributaries, that formerly were filled with

happy vacationists, were taken over by workers. Some, and especially those

with children, sought farm homes for a place to live. Still others brought

tents and camped out wherever they could find an available spot.

Public health authorities tried to protect the health of these immigrants

by imposing certain standards, but it was necessary to be as lenient as

possible with offenders for circumstances sometimes made it impossible for

the transients to comply with all the regulations.

The problem of police and fire protection placed an added bur-den on local

governments. Although a temporary hospital was set up by the construction

companies on the camp grounds for emergency treatment of injured workmen,

many victims of construction or traffic accidents reached the Bartholomew

County hospital and filled it to capacity.

About 700 cars carrying workmen were entering the camp daily during the

busiest period. The Indiana Chamber of Commerce suggested four ways of

meeting the demand for increased transportation facilities: use of school

buses; the use of passenger cars owned by workers on a share-the-ride and

share-expense plan; conversion of passenger cars into buses; and an

increase in licensed buses.

Arthur Givens, a Columbus truck operator, received a permit to operate a

bus line between Columbus and the camp entrance, thence to Franklin,

Shelbyville, Hope, and back to Columbus. Temporary permits were issued for

bus lines to Ray I. Allen, operating between Martinsville and Edinburg

over Road 252, and Wilson-Kidwell, Inc., of Seymour, operating on Road 31

between Scottsburg and the camp entrance.|

Plans for converting U. S. 31 into a dual highway, from the point where it

by-passed Columbus, to Greenwood, were announced by the State Highway

Department early in the year, but lack of materials prevented this being

done in time to ease the traffic jams created by the construction workers.

The Standard Concession Company of Franklin, headed by V. R. Terrill,

established the first eating place for workers at the camp.

It was part frame and

part tent, and was designed to feed 600 workers at a time. Box lunches

were prepared for those who desired them. All meats had to be supplied

from establishments operating under United States inspection or

state-approved inspection. Only pasteurized milk could be served and that

was subject to frequent inspection by the State Board of Health. Despite

these precautionary measures, the flies and the dust created a problem in

sanitation. Out-side the camp area, new eating places sprang up along Road

31, and additional restaurants were opened in Columbus, Edinburg, and

Franklin.

The payroll of the workers reached a half million dollars weekly during

the peak period. The rush in business at the money order windows of the

local post offices indicated that a portion of it was sent home, but much

was spent in the community for housing, food, clothing, and entertainment.

The local stores found their stock of supplies constantly depleted. In the

evenings and on rainy days when they could not work, the transient

population crowded into the towns seeking diversion. Places of

entertainment were few. Taverns did a rushing business.

Early in the spring a dispute arose over the wage rate to be paid

carpenters. The rate in Columbus was $1.00, while in Indianapolis it had

been raised from $1.30 to $1.42½ in January. The construction companies

stated that the contracts had been drawn up and accepted on the $1.30

basis, even though the officers of the carpenters' union had advised the

government and the companies of the increase. Some of the companies seemed

willing to pay the larger sum; others refused. A walk-off (not a strike)

of 271 carpenters occurred April 25, 1942. A petition was circulated and

dispatched to the U. S. Department of Labor, asking it to settle the

dispute. Lieut. Gen. B. Somervell, Army Supply Chief, decided that the

$1.30 rate was the one that should be followed.

The Blair Company, contractors for three fourths of the barracks, turned

them out almost like automobiles, only instead of the buildings moving

down the assembly line, the workers moved to a new building. Lumber for

the framework was cut to length in the lumber yard as soon as it was taken

off freight cars. By cutting all the pieces exactly as they were to be

used, the framework was almost in a prefabricated stage when the

carpenters started pounding the nails. The pre-cut lumber included that

for joists, beams, braces, sills, stairs, flooring, chimney frames, etc.

After it was cut, it was trucked to the various depots in the area where

the buildings were to be built. Crews of workers, each crew doing a

particular job, went from building to building, completing their

particular work. The barracks were two-story structures, covered with

asbestos shingles or wood siding. Some were not painted; others were

painted white with cream trim.

On some projects work was on a 24-hour basis. Sand, gravel, and crushed

stone for foundations and for roads were obtained from near-by gravel pits

and quarries. As much as one hundred tons a day was used at times. Dump

truck after dump truck moved in a continuous line into the construction

area. An asphalt plant for processing the blacktop laid on top the gravel

roads was set up on the ground.

August 1 was the date set for completion of the major construction. It was

a race against time, but as the deadline approached the camp began to

assume some semblance of order. WPA workers and trucks were called in to

assist in the road work. Boys from the CCC camp in Brown County helped

greatly in clearing up debris. After the middle of June the number at work

in the camp area decreased appreciably. The departure of workers, however,

did not lessen the demand for living quarters for by this time Army men

were arriving in ever increasing numbers and seeking homes for their

families.

On August 15, the date set for reactivation of the Eighty-third Division,

the public was invited to see Indiana's largest and newest Army camp. It

was a field day for Hoosiers. Despite rain some fifteen thousand poured

into the camp. Lieut. Gen. Ben Lear, commanding officer of the Second

Army, was present, as was Governor Henry F. Schricker of Indiana. After

the colorful and impressive reactivation ceremonies were over, the people

roamed over the area, peering into hundreds of buildings to see how the

soldiers would live and eat. All types of fighting equipment were on

display in the large sports arena. Guns ranged from the 4½ ton howitzers

to the smallest of defense weapons. There were walkie-talkie sets, gas

masks, Army vehicles of all descriptions, flame throwers, pontoon bridges

and boats, gun emplacements, mobile machine shops, and a portable water

purification set. There was even a fox hole. It was a rare opportunity for

the civilian, and one that was bound to promote closer understanding

between the camp and the community. When the time came to leave, the

visitors were a tired lot, but they understood better what the Army was

trying to do. In the days to come they could appreciate better the life of

the soldier and try to help him in his off-duty hours. As the last of the

guests departed, and darkness enveloped the countryside, the camp settled

down to the serious and grim business of training an Army for war.

NAMING THE CAMP

Proposed names for the

new camp began to come into the news-paper offices soon after its

construction was announced. Among the names suggested were: Camp

Bartholomew, for Joseph Bartholomew, Indiana pioneer and Indian fighter;

Camp MacArthur, for Gen. Douglas MacArthur; Camp Tipton, for John Tipton,

original owner of a part of the land on which the town of Columbus was

platted, and later a United States Senator; Camp Amity for the town of

that name in Johnson County; Camp Snyder, for Col. John Snyder, an officer

in the War of 1812 who is buried in Bartholomew County; and Camp Kelley,

for Capt. Colin Kelley of the Army Air Corps, who had lost his life in the

bombing of a Japanese ship early in the war.

On February 16 came the announcement from Washington that the camp had

been given the name of Atterbury in memory of

Brig. Gen. William Wallace

Atterbury, a Hoosier who had performed distinguished service in World War

I. When the people of the neighborhood learned more about Atterbury, they

could only approve of the choice.

Born in New Albany on January 31, 1866, Atterbury had begun his career as

an apprentice with the Pennsylvania Railroad. He had worked up to the

vice-presidency of the railroad company by 1917. When General Pershing

called that year for "the ablest railroadman in the United States" to

handle the transportation of American soldiers, equipment, and supplies to

Europe, Secretary of War Newton D. Baker selected Atterbury and sent him

to Europe as director general of transportation with the rank of brigadier

general.

Gen. Atterbury's work abroad included the construction and operation of

enormous harbor and railroad facilities, and in harmonizing these with the

facilities of the Allies. Aided by a staff of picked railroad men selected

by himself, he carried out his task with such conspicuous success that it

won immediate acclaim. His own country conferred upon him the

Distinguished Service Medal, and France, Great Britain, Belgium, Serbia,

and Rumania each honored him with high military decorations.

At the close of the war, Atterbury returned to civilian life and to his

work with the Pennsylvania Railroad. In 1925 he became president of the

company and continued in this capacity until shortly before his death on

September 20, 1934. Born into a family of moderate circumstances, but one

that believed in education, Gen. Atterbury's life typifies the American

idea of opportunity that is available to all who are willing to work. It

is fitting that Indiana's largest training camp of World War II should be

named in his honor.

CAMP ATTERBURY AS A

TRAINING CAMP

Combat Divisions

The purpose of building

Camp Atterbury was to train soldiers for combat. The divisions which

trained at Atterbury during different periods of the war were the 83d

Infantry Division; a combat team of the 92d Division; and the 30th and

106th Divisions. In addition there were many auxiliary and service units

and a number of small unattached units.

As a result of experimentation after World War I, the composition of the

Army's divisions had been changed from "square" to "triangular." Under the

old plan a division was built around two brigades of two regiments each,

while under the new plan a division was built around three infantry

regiments. This triangular arrangement extended down to the division's

tiniest unit, the rifle squad.

For example, each

regiment consisted of three battalions and sup-porting troops; each

battalion of three rifle companies and support; each company of three

rifle platoons and support; and each platoon of three rifle squads. A

regiment assisted by a battalion of light field artillery formed a combat

team. There were four field artillery battalions in each division.

To make a division completely self-sustaining, there were added to it,

besides the regimental troops and field artillery, engineer and medical

battalions, a cavalry reconnaissance troop, a headquarters company,

signal, quartermaster, and ordnance companies, a military police platoon,

chaplains, and a band.

In combat, the division usually had attached to it airborne troops, tanks,

tank destroyers, anti-aircraft artillery, hospital units, and a number of

special detachments.

Early in July, 1942, two hundred men arrived at Camp Atterbury to form a

cadre for the new 83d Division, and on July 10, Maj. Gen. John J.

Milliken, a Hoosier from Danville, who was to be commanding officer, came

from Camp Funston, Kansas. A month later he was transferred to Camp

Forrest, Tennessee, and another Hoosier, Brig. Gen. Frank W. Milburn,

succeeded him. On July 16, Camp Atterbury welcomed its first large

contingent of troops. These soldiers had been in service for some time and

were prepared to assist in the training of the new selectees that arrived

in August. Fifteen thousand men were at the camp by August 15 when the 83d

Division was reactivated. Later, it and its auxiliary forces included

about 25,000 men.

The 83d Division was originally organized in 1917 at Fort Sherman, Ohio,

and was made up largely of men from Ohio, western Pennsylvania, and West

Virginia. After achieving a brilliant record in World War I, it was

demobilized. Now the time had come for the writing of another chapter in

the division's history.

General Milburn, new commander of the 83d, was born at Jasper, Indiana,

and graduated from West Point in 1914. He came to Atterbury from service

with the Eighth Motorized Division. He had spent several months during

1941 with the British Army in Egypt, observing methods of desert warfare.

It was his aim to make every soldier under his command a leader instead of

a follower. He insisted that every man learn to do the individual thinking

his job required.

The 83d included the 329th, 330th, and 331st infantry regiments, the 322d,

323d, 324th, and 908th field artillery battalions; the 308th medical

battalion, the 308th engineers, and the headquarters, signal,

quartermaster, and ordnance companies called for under the plan for

divisions mentioned above.

The usual pattern of training was first to give each soldier individual

training for the job he was to perform, after which he learned to work as

a part of a small unit; then small units learned to work together and so

on up the scale until in the final stage all the component parts of a

division learned to function as a coordinated whole.

There were 21 firing ranges at Atterbury, located in Bartholomew County,

south of the cantonment area. Facilities were available for firing every

type of weapon used by the Army Ground Forces. The basic weapons used by

the infantry were the .45 caliber pistol, rifle, bayonet, hand grenade,

Browning automatic rifle, light machine gun, 60 mm. mortar, heavy machine

gun, 81 mm. mortar, and the light carbine.

The entire range area was controlled from the range control office. When a

unit commander desired the men in his organization to fire, he sent a

written request to the range officer, stating the type of weapon to be

fired, the type of targets desired, the preferable dates for firing, and

the number of men to participate. The range officer consulted the firing

schedule and arranged for the request to be granted, allowing the

preferred dates if possible. When the unit arrived at the designated

range, all was ready for action.

The first firing was usually done on the rifle range. Then as a soldier

advanced in training he learned to use other weapons. The first practice

was without ammunition. The longest range was the artillery range, 9 miles

in length, with 4 firing points at each end, and shells traveling toward

the center of the range. Eventually the soldiers saw action on one of the

5 combat ranges where actual battle conditions were simulated.

An "enemy" town which the soldiers named Tojoburg was built in the range

section of the camp. It contained some 30 buildings representing a post

office, communications center, hotel, tavern, church, town hall, etc. Most

of these were occupied by dummies that made unpredictable appearances.

Capture of the village represented a field problem. The soldiers were

taught how to approach the town, how to recognize the various types of

buildings, and how to over-come the "enemies" that might be lurking there.

In March, 1943, a school for Rangers, the United States counter-part of

the British commandos, was set up by the 83d Division. Lieut. Gen. Ben

Lear had announced a desire to have every man in the Second Army a Ranger.

The main features of this training consisted of running a super-obstacle

course (nicknamed the blitz course), hand to hand combat with no holds

barred, demolition, snap firing, and personal camouflage. General Lear

made his third visit to Atterbury to watch this Ranger school in action.

The heart of the training was the blitz course, 1,000 yards of the

toughest obstacles that could be conceived; 10-foot leaps over

barbed-wire-filled trenches; 8-foot walls to scale; barbed wire to crawl

through; dummy enemy soldiers appearing from nowhere as bayonet targets;

and stream crossings on narrow logs over mined waters, all done under

simulated shell fire and smoke. The goal of the Rangers' school was to

turn out the toughest, hardest fighting men in the world.

Seven Rangers returned in December, 1943, from the battlefields of Africa

and Italy to help train the men at Atterbury. They had a trunkful of

decorations. It was impossible to get any of these taciturn,

battle-hardened soldiers to talk about individual feats, but they took

great pride in passing on to every soldier the lessons learned, in order

to save countless thousands of lives on battle fronts all over the world.

The middle of June, 1943, found the 83d preparing to leave Atterbury for

Second Army maneuvers in Tennessee. As a farewell event, they staged a

field day on June 16 to which friends and relatives were invited. There

was a full day of athletic events, military demonstrations, a parade, and

a dance in the sports arena that night. In September, 1943, the Division

moved to Camp Breckinridge, Kentucky, and in April, 1944, sailed for

England under the command of Maj. Gen. Robert C. Macon. On June 18 they

began landing on the Omaha beach of Normandy. They launched their first big

offensive on July 4, breaking through the St. Lo-Coutances high-way. Early

in August they moved to Avranches and then on to the fortress of St. Maio

which they captured on the 17th. The following month they operated in the

Loire Valley, covering a 200-mile line from St. Nazaire to Auxerre,

capturing 20,000 Germans at one time. Late in September they headed

northeast through France and Luxembourg. Early in December they moved into

the Hurtgen Forest to relieve the 4th Infantry Division and from there

fought their way to the west bank of the Roer near Duren. During the

German counteroffensive, the 83d was ordered to Rochefort where they

fought in waist-high snow and bitter cold to help turn back the enemy

assault. A month later they were assigned to the Ninth Army and crossed

the Rhine on March 30 after taking Neuss. Their next objective was the

Hamm railyards, where they seized enough abandoned vehicles to completely

motorize themselves, and then raced east to the Elbe, capturing 24,000

Germans and liberating 75,000 Allied prisoners on the way.

(1)

Following the German surrender and the return of the troops to the United

States, the Division was deactivated. The following year, in 1946, it was

again activated to serve as a reserve division of Indiana and Ohio units.

Two units of the 92d Division were in training at Atterbury at the same

time as the 83d. These were the 365th Infantry Regiment and the

597th

Field Artillery Battalion composed of Negro selective service men. These

units were formally reactivated at Atterbury on October 15, 1942, as a

combat team. On the same day, similar reactivation ceremonies were held at

three other camps for other units of the Division.

The 92d had seen action in France during World War I. The cadre for the

combat team at Atterbury came from Fort Huachuca, Arizona. Col. Walter A.

Elliott was the commanding officer. The Division mascot was a live

buffalo.

The above units of the 92d trained at Atterbury until April 26, 1943, when

they joined the rest of the Division at Fort Huachuca. They practiced

large-scale maneuvers with the Third Army from February to April, 1944.

The Division sailed for North Africa in June, 1944, but their ultimate

destination was Italy where they were assigned to the Fifth Army front in

the Italian Apennines. Their first large-scale attack as a division was

made in February, 1945, when they were given the mission of seizing Mount

Cassala, a peak dominating the western coast ports. After succeeding in

this mission they worked up the Ligurian coast and seized La Spezia and

Genoa, and then continued northward to take Alessandria and Turin.

(2)

The 30th Infantry Division, commanded by Maj. Gen. Leland S. Hobbs,

arrived at Camp Atterbury on November 13, 1943, from large-scale field

maneuvers in Tennessee. This division was originally created in July,

1917, during World War I. It was composed of National Guard troops from

Tennessee, North and South Carolina, augmented by selective service troops

from Indiana, Illinois, Iowa, Minnesota, and North Dakota, and was known

as the "Old Hickory" Division in honor of Andrew Jackson. It was disbanded

after World War I, but was reactivated in 1925 as a National Guard

division. It was called to full-time duty in 1940, one of the first four

guard units to be called.

At the time of its training at Atterbury, it was composed of the 117th,

119th, and 120th infantry regiments; the 113th, 118th, 197th, and 230th

Field Artillery battalions, the 730th Ordnance Light Maintenance Company,

the 105th Medical Battalion, and the 105th Engineer Battalion, signal and

quartermaster companies, reconnaissance troops, and a division

headquarters and headquarters company. The 743d and 823d tank destroyer

battalions and the 531st anti-aircraft artillery battalion were attached

to it. Their brief stay of ten weeks at Atterbury was spent in preparation

for movement overseas. On January 30, 1944, they left for Camp Myles

Standish, Massachusetts, and sailed on February 12 for England. On June 15

they joined the fighting in Normandy. After heavy fighting in France they

crossed the Seine in September and became the first

American division to enter Belgium and Holland. On October 2 they attacked

the Siegfried Line and broke through at Palemberg and Rimburg. They

advanced on into Germany and were near Magdeburg on the Elbe when Germany

surrendered. (3)

The next division to train at Atterbury was the 106th

Infantry Division which arrived the

last of March, 1944, from Second Army maneuvers in Tennessee. It was a

comparatively new organization having been activated at Fort Jackson,

South Carolina, on May 15, 1943. It was composed largely of younger men

from Indiana, Illinois, and South Carolina. Maj. Gen. Alan W. Jones was

the commanding officer. The division included the 422d, 423d, and 424th

infantry regiments, the 589th, 590th, 591st, and 592d field artillery

regiments, the 806th ordnance company, and other auxiliary units. Students

in the Army Specialized Training Program, who had been enrolled in

colleges, were assigned to the 106th after the curtailment of the program.

The Division remained at Atterbury until the middle of October, 1944, and

then was sent overseas. Being without combat experience, the troops were

assigned what was supposed to be a relatively quiet sector in the

Ardennes. About a week later, on December 16, came the German

counteroffensive, the heaviest blow of which was directed along the line

where the 422d and 423d regiments of the 106th were stationed. Though

vastly outnumbered, they held out for two and a half days; then being shut

off from other troops and without food, water, or ammunition, they

radioed, `We now are destroying our equipment." 'When the casualties were

counted, it was found that 400 were killed and 1,200 wounded; some 7,000

were taken prisoners. Those that escaped moved to the rear for

reorganization and then returned to the front at once to help finish the

Battle of the Bulge. After V-E Day the 106th was given the job of guarding

thousands of German prisoners of war.

(4)

Service Forces

In the reorganization of

the War Department in March, 1942, the Army was divided into three parts

for training purposes: the Army Ground Forces, Air Forces, and Service

Forces. The first two were trained as combat units. The Service Forces

were trained to maintain, equip, transport, and care for the other two

forces, both in training and in battle. The technical, judicial,

quartermaster, ordnance, engineering, signal, medical, chaplains' corps

and military police organizations were part of the Service Forces. They

operated the telegraph, telephone, radio, and electronic devices; they

kept the Army's records, paid its bills, and paid each individual soldier

and his dependents. They maintained the Army's health and took care of the

sick and wounded. They were responsible for the morale of the troops, and

in this connection operated theaters and other recreational facilities.

They were also responsible for administering military justice, handling

prisoners of war, maintaining law and order. In addition to performing

their particular service job, these men had to be first-class fighting

men, ready to take their place by the side of the regular infantryman in

battle.

Medical units that trained at Atterbury included general station,

evacuation, and portable surgical hospitals, ambulance companies, and

supply depots. Ordnance units ranged from light to heavy maintenance

groups, while military police included combat, escort, guard, and aviation

guard organizations. The members of the medical units used the facilities

of the post hospital and later of the Wake-man hospital in their training

and also practiced in the field. They had to learn to move their equipment

at a moment's notice and set it up in another area. Some were organized to

give emergency treatment, others prepared to operate farther back of the

lines.

Men in the ordnance units learned to service all types of motor vehicles

in the regular machine shops; then they were taken on field trips where

they learned to work under simulated battle conditions, repairing vehicles

in the open from portable machine shops and with a minimum of equipment.

They learned to camouflage their bivouac area and to defend themselves in

case of attack. They also took care of the guns. The quartermaster bakery

battalion learned to bake bread in the open regardless of the weather.

Their toughest test was baking under blackout conditions.

In addition to the service troops attached to the divisions, a number of

the men belonged to units of the Eighth Detachment, Special Troops, Second

Army. This included the 338th Engineers, the 457th Engineer Depot Company,

the 249th Quartermaster Service Battalion; the 329th Quartermaster Depot

Company; Company C of the 100th Bakery Battalion; the 30th, 31st, and 42d

Signal Construction Battalions, the 301st Signal Operations Battalion,

several ordnance companies (the 122d, 349th, 377th, 895th, Co. C of the

95th Battalion, the 3532d) and the 210th Ordnance Battalion, the 35th,

39th, and 44th evacuation hospital units. Their job was to prepare the way

for invasion troops and their training was directed toward that end. Units

of the detachment were in training at Atterbury during different periods

from September, 1942, to June, 1944. They were commanded by Col. Richard

C. Stickney.

Then there were other service units that performed jobs necessary to the

operation of the camp. These included the Women's Army Corps, the men in

charge of the prisoners of war, and those who worked in the hospital and

in such departments as quartermaster, transportation, ordnance, and

finance. After the personnel center was set up at Atterbury in 1944, it

was staffed by service units. The work of some of these units is brought

out more particularly in other chapters. One that might be mentioned here

is the 1584th that had charge of the special training classes.

An average of one person out of every twelve inducted in the Fifth Corps

Area was found to be deficient in his education to the point that he could

not keep up with his fellow soldiers. To take care of these men a special

training unit, the 1584th, was activated at Camp Perry, Ohio, in 1941. It

was moved to Fort Harrison in June, 1943, and to Atterbury in November of

that year. It was re-designated the 1560th SCU Special Training unit on

February 1, 1945.

Both educational and military fundamentals were taught the men assigned to

this unit. The former consisted largely of the 3 R's and was intended to

give the average trainee the equivalent of a fourth-grade education. The

latter included the organization of the Army, military discipline and

courtesy, articles of war, sanitation, first aid, guard duty, the

safeguarding of military information, and many other subjects that would

enable the trainees to become better soldiers. They practiced infantry

drilling and rifle marksmanship. On off-duty hours the men participated in

sports, and put on talent shows; they organized a "mountain music"

orchestra which played for square dances.

A number of the academic instructors were civilians. Much of the

instruction was individual inasmuch as the background and capabilities of

the students differed. The majority of the trainees were ready to leave

the unit in six or eight weeks. As soon as a trainee was considered to be

competent to proceed with the regular military training, he was sent back

to the reception center for regular assignment to a training camp.

Another service unit, the 1562d, operated the Camp Atterbury school for

bakers and cooks.

The Women's Army Corps

President Roosevelt

signed on May 15, 1942, the act creating the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps.

Recruiting began almost immediately and training centers were established.

It was not quite a year after organization of the Corps that the first

contingent of WAACs, 130 members of the 44th Headquarters Company,

de-trained at Camp Atterbury, on March 6, 1943. They came from the

training center at Daytona Beach, Florida. The company consisted of a

clerical platoon, a service club platoon, and units of theater ushers,

motor transport drivers, cooks, bakers, and basics. Heading the company as

commander was Second Officer Helen C. Grote, of Neola, Iowa, who had been

a law secretary at Salt Lake City before her induction and training at the

Officers' Candidate School at Fort Des Moines, Iowa.

Five buildings were ready for the WAACs, including a combination

administration, officers' quarters, and recreation building, a mess hall,

and three barracks. These buildings, constructed after the original

portion of the camp, were located in a separate block at the rear of the

post headquarters buildings. They were like those used by the men except

there was a beauty parlor in the administration building and a special

laundry room in each of the barracks buildings.

This headquarters company filled various jobs ranging from chauffeurs and

typists to theater managers and librarians. They were assigned to such

offices and branches as special service, motor pool, quartermaster, post

locator, military personnel, and adjutant. Their service released many men

for combat duty.

A detachment of 141 Negro members of the WAAC were the next to arrive,

coming on May 22, 1943. This group was activated as the medical section of

the 3561st Service Unit and was commanded by Second Officer Sarah E.

Murphy, of Atlanta, Georgia, a former newspaper reporter and

schoolteacher. This unit worked in the post hospital as ward attendants,

ambulance drivers, dental assistants, medical technicians, cooks, clerks,

typists, and stenographers. On June 21, the 44th Post Headquarters Company

became the Headquarters Section of the 3561st Service Unit.

Legislation changing the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps from an auxiliary

unit into a unit of the Regular Army was signed by President Roosevelt on

July 2, 1943. In a colorful ceremony held on August 10, the two companies

of Atterbury WAACs were officially sworn into the Army as members of the

Women's Army Corps.

The WACs played a major role in the care of the wounded re-turned from

overseas. When the soldier left his hospital ship, his ambulance driver

was a WAC; as he entered the hospital the GI found trained Women's Army

Corps technicians working in surgical wards, operating rooms, dental

clinics, medical laboratories, and X-ray room, assisting over-worked

doctors and nurses.

The mounting casualty lists that came with the invasion of France

increased the need for more trained technicians. In July, 1944, it was

decided to move the WAC Medical Department Enlisted Technicians' School

from Hot Springs, Arkansas, to the Wakeman General Hospital at Atterbury.

Fifty buildings in Block 7 were assigned to the school. Students and

instructors from the Arkansas school arrived on August 4; there were 22

enlisted women, 9 officers, and 93 students. Classes were resumed on

August 10.

The school was organized

into five sections: dental, medical, surgical, laboratory, and X-ray. In

order to be accepted for training, WAC members had to be high-school

graduates, and it was better if they had had previous training or

experience as nurses' aides. They had six weeks of basic training before

entering the technicians' school. The shortest course was the dental

section which could be covered in twelve weeks. Four months were required

to complete the medical and surgical sections. After December 8, 1944,

students in these two sections received only the first two months of

training at Atterbury and were sent elsewhere for the remaining two

months. Graduations and departures occurred each month and were followed

by the arrival of new students. With the closing of a similar school at

Billings hospital, Fort Benjamin Harrison, in February, 1945, instructors

and equipment were transferred to the Atterbury school.

In March, 1945, 408 new students were enrolled; this was 148 over the

regular quota. In April the number of new students was 457, and the total

enrollment reached 726. Additional classrooms and teaching personnel were

badly needed. Four months later, in August, came the announcement that no

more new WAC students would be received, and that when those in attendance

had completed their course the school would be converted into a training

school for men.

During the period of a little over a year that the school was conducted,

some 3,800 WACs received training in one of the five courses. Some of

these remained at the Wakeman hospital; the rest went to other Army

hospitals scattered over the country. With 30,000 casualties a month being

returned to hospitals in the United States, these women were able to make

a great contribution toward caring for the sick and wounded.

On May 14, 1945, the WACs at Camp Atterbury celebrated the third birthday

of their corps. Of the 130 members of that first contingent that arrived

at the camp, 20 were still there. From the ranks of all those stationed at

Atterbury, 47 had gone overseas. Some returned after serving as much as

eighteen months overseas on many different battle fronts. Many had been

decorated. Great

praise goes to these loyal women who sacrificed much and performed a

wonderful service.

ADMINISTRATION OF THE

CAMP

The administration of a

camp the size of Atterbury was equivalent to managing a city the size of

Anderson. The office of post commander was analogous to that of mayor.

Functioning under the commander were the heads of various divisions,

similar to a mayor's administrative assistants. The administrative

personnel remained fairly permanent during the war period. They were

responsible for the smooth running of the camp. Combat divisions and units

moved in and out at frequent intervals, with the administrative personnel

preparing for their arrival and taking care of their needs while there.

One can get some idea of the administrative set-up of the camp from the

following chart which appeared in the Camp Crier, March 31, 1944:

Post Commander—Col. Welton M. Modisette

executive officer

assistant executive officer

post inspector control officer

public relations officer

Staff Divisions

Post adjutant

assistant adjutant

billeting officer

postal officer

Post judge advocate

legal assistance and claims officer

Personnel division

military personnel

civilian personnel

post chaplain

personal affairs branch

morale service branch

special service branch (service clubs, theaters, athletics) post exchange

Supply and service division purchasing and contracting storage and

maintenance

Internal security and intelligence assistant director

intelligence officer

prison officer

Military training division range officer

range supply officer

Fiscal division

post fiscal officer

Technical Services

Post surgeon

commanding officer, station hospital

chief of dispensaries veterinarian

chief nurse

sanitary officer

medical supply

Post engineer

executive and maintenance officer

administrative and property officer

operations officer and assistant fire marshal

senior engineer

Post quartermaster executive officer

post food supervisor property officer

motor transportation officer

salvage officer

laundry officer

commissary sales officer warehouse officer

bakery officer

clothing sales officer

classification officer

Post signal officer

Post transportation officer Post ordnance officer

Post chemical warfare officer Engineer property officer

The post adjutant disseminated all War Department regulations and those

issued by the Fifth Service Command, and issued orders relating to

military personnel such as assignments, transfers, pro-motions; the

billeting officer allocated and provided space for housing; the postal

officer distributed mail through the message center and inter-office

communication system.

The judge advocate handled all legal matters pertaining to the camp and

reviewed claims and court-martial cases before submitting them to the

commanding officer; the legal assistance and claims officer helped

soldiers in the preparation of legal papers. The supply and service

division had charge of purchasing food, clothing, equipment, and

ammunition for the soldiers and of storing it so it would be available

when needed.

The internal security and intelligence division was responsible for the

security of the camp; it coordinated Army regulations with those of

civilian authorities in near-by towns, apprehended AWOLs and issued passes

for civilians and visitors. The military police handled traffic at the

post and furnished details of military police in surrounding cities and

towns; they furnished guards and sentries for post installations and took

care of the feeding and quartering of war dogs. The prison officer kept

records pertaining to the prisoner of war camp and handled details

connected with the employment of the prisoners by civilians.

Under the military division the range and range supply officer made

schedules for the use of the firing ranges and supplied the ammunition and

targets desired. The fiscal officer supervised all financial matters

pertaining to the post and provided for the payment of personnel.

The work of the technical services is more or less self-explanatory. When

the Atterbury Station Hospital became a General Hospital Center, the

administration of all affairs connected with it became the responsibility

of the hospital's commanding officer and was no longer under the

jurisdiction of Colonel Modisette.

Col. Welton M. Modisette was appointed Atterbury's first commanding

officer. He arrived on the scene late in May, 1942, just as construction

was getting well under way. He continued in command during the time that

the camp was a training center. In June, 1945, he was succeeded by Brig.

Gen. Ernest A. Bixby who remained in charge during the time the reception

station and the separation center were at their peak. In June, 1946, as

the time approached for the closing of these installations, General Bixby

was succeeded by Col. Herbert H. Glidden. He remained two months and was

followed by Col. John L. Gammell who, in turn, was followed by Col. Carter

A. McLennon in September, 1946. Col. McLennon super-intended the final

closing of the camp at the end of the year.

PRISONERS OF WARS

On May 19, 1943, Col.

Welton M. Modisette, post commander, announced that Italian prisoners of

war at the internment camp at Atterbury were available for agricultural

labor in the five counties within a 25-mile radius of the camp. Requests

were to be made for their labor through the county agricultural agents to

the internment camp commander, Lieut. Col. John L. Gammell. This

announcement was the first published reference about the internment camp,

al-though its presence was known earlier to some.

Many farmers availed themselves of this opportunity to get much-needed

help. The provision for use of prisoners only within a 25-mile radius was

lifted to permit their use on farms as far distant as Decatur County. The

farmer hiring prisoner labor had to provide transportation, equipment and

tools, toilet facilities, and safe drinking water. As a rule not less than

ten men were to be sent out on any one job. Contracts stipulated the type

and amount of work to be done, the location of the farm, number of working

hours, and amount of pay. Work of a dangerous nature was prohibited, and

prisoners were not to be employed except in cases where the demand could

not be filled by civilian labor. The working day was limited to ten hours,

including travel time to and from work. A guard accompanied each group of

prisoners to and from the camp and stayed with them while they worked.

Payment for the labor was made directly to the United States Government at

the prevailing wage rate of the vicinity after the cost of transportation

and food furnished the prisoners was deducted.

Each prisoner received from the government a flat allowance of ten cents a

day and an extra eighty cents for each full day's work outside the

stockade. He could receive up to $13 a month of this money in coupons

exchangeable at the canteens, but any amount earned over this sum was kept

in trust for him until such time as he should be repatriated.

On June 4, 1943, Army headquarters in Washington announced that Camp

Atterbury's prisoner of war camp would be one of the permanent internment

centers. Newspaper men were taken on a tour of the camp on June 5. They

found it located in a secluded valley at the west edge of Camp Atterbury,

well away from the training area. It was enclosed within a double barbed

wire fence, with guard towers covering a narrow alley between the fences.

The stockade was divided into three compounds, each containing hut

shelters, mess halls, toilet facilities, and other installations

sufficient to accommodate 3,000 prisoners.

The prison camp at this time required the services of approximately 500

Army officers and enlisted men, who were housed outside the stockade in

near-by barracks. The guard and administrative detachment was made up of 3

military police escort companies, 21 additional officers, and 3 attached

officers. The guard companies rotated; while one was on actual camp guard

manning the towers and gates, another company was on the alert, and the

third was engaged in tactical and other training exercises or in

supervising work details.

The unit in charge of the

internment camp was the 1537th Service Unit. It had been activated on

December 15, 1942, with 50 enlisted men; during the following six weeks

these men received specialized training for their job. Then on February 10

they moved to the internment area and spent the next two months in

converting it into a prison camp and making all the necessary preparations

for the arrival of the prisoners. There was no complete standard operating

procedure for prisoner of war camps at this time; as a result,

regulations, forms, and records had to be initiated and a fiscal system

set up.

Two MP Guard companies arrived from Fort Custer, Michigan, on April 18 to

take over the guard duties. On April 30 the first contingent of 767

prisoners arrived; the following day 400 more were checked in. By

September the number reached 3,000.

The camp was organized as a regiment of three battalions of five companies

each. Each battalion was composed of one escort guard company of American

soldiers and four companies of prisoners. The prisoners had one

regimental, three battalion, and twelve company leaders appointed from

their own ranks by the camp commander. The prisoners were given a basic

course which included common English words, recognition of the American

national an-them, bugle calls, Army insignia, various commands, etc. The

prisoners received the same rations as the American soldiers except that

at their own request the Italians received extra flour in lieu of meat.

This was in line with their normal diet. They baked their own bread, made

spaghetti, and prepared their own meals. They were permitted and expected

to organize and administer their own affairs as much as possible. There

were no commissioned officers among the Italian prisoners.

The sick and wounded among the prisoners were moved immediately to the

post hospital. Dispensaries within the stockade took care of temporary

illnesses. Many could not understand how they got to Indiana, believing

that it was a part of India. Others expressed wonder that New York City

could have been rebuilt so quickly. They had understood that it had been

destroyed by bombs. Almost all of them were Catholics. Maurice F. Imhoof,

an American Catholic priest, who had studied in Rome and spoke Italian

fluently, was chaplain for the internment camp. The prisoners showed their

artistic ability by erecting in their spare time a beautiful outdoor altar

of brick and stone.

The reporters were impressed most by the cheerfulness of the Italians and

the excellent condition of the camp. The newcomers, dumped suddenly into

an unknown land, thousands of miles from home, constantly grinned, talked

and joked, played a queer game with their fingers called "La Mora," and

sang in lusty voices as they marched to and from work assignments. They

had day rooms with radios, phonographs, games, and approved newspapers and

magazines in Italian; there was also a recreation area, with equipment for

volley ball, soccer, and other games. Most of these "extras" were

purchased with the profits realized from the operation of the can-teens in

the stockade. This money was also used to buy musical instruments for the

prisoners. On Sunday morning the prisoners were permitted to see movies at

the Camp Atterbury theaters.

Lawnmowers were one of the many American novelties to the Italians. They

asked to be allowed to cut grass so that they could operate the mowers.

They also worked in the post garden, the laundry, and at other tasks

around the grounds. Each prisoner was required to send a card home telling

of his safe arrival at the internment camp; after that he could send one

card and two letters each week. Both incoming and outgoing mail was

censored. Prisoners were permitted to have visitors twice a month. These

visits were under the supervision of military personnel and were limited

to two hours.

Meanwhile the war had not been going so well for the homeland of the

prisoners. On September 8 the Italian Government surrendered to the

Allies, but the war was continued in Italy by the Germans. In January,

1944, the first of the Italian prisoners at Camp Atterbury were

transferred to other camps prior to their return to their homeland. A few

of them joined newly formed volunteer non-combat units in the United

States Army. Their removal from Atterbury was completed by May 4. It was

during this period, in February, that the first and only death of an

Italian prisoner occurred.

The Italian prisoners

were replaced by German prisoners, the first ones arriving on May 8, four

days after the departure of the last group of Italians. There were 2,940

Germans in the internment camp by June 30 and 5,700 on September 19. This

was far beyond the original capacity of the camp. In the following months

some of these were transferred to other camps and new groups were received

at Atterbury. The maximum was reached on October 15 when there were 8,898

prisoners; 3,700 of these were in branch camps established at points

throughout the state, the remainder were at Atterbury. Army troops in

charge of the prisoners on this date numbered 746 enlisted men and 33

officers.

There was quite a difference between the German prisoners and the

Italians.

The Germans, particularly the thorough Nazis, were still definitely

enemies, although deprived of the power to do any-thing about it, while

most of the Italians had been lukewarm enemies before they were captured,

and enemies not at all as soon as they were taken. The German prisoners

were still essentially hostile, although so well disciplined and well

handled that they constituted no particular threat. Like the Italians,

they were hired out as agricultural laborers and as workers in the canning

factories. Earnings of these German prisoners in the month of October,

1944, reached $135,000. On some days there were as many as 750 different

work details. The average daily wage paid for a prisoner of war to the

government was $4.00, the labor being classified as unskilled on the

majority of projects. During the height of the canning season, branch

camps were established at Austin, Windfall, Vincennes, Eaton, and

Morristown so that workers would be available in those areas. These camps

continued to be maintained during the winter months in order to take care

of the large number of prisoners under the jurisdiction of the Atterbury

prison camp. In addition to the sums earned at outside labor, the