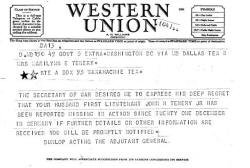

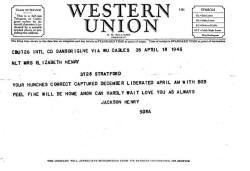

|

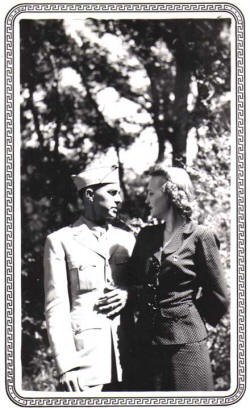

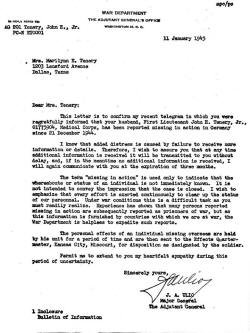

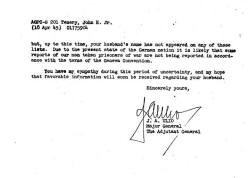

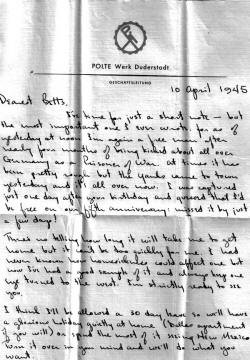

Chapter One Accidental Soldiers of the 106th Infantry Division With the officers and enlisted men of the 106th Infantry Division assembled in the Post Theater at Camp Atterbury, Indiana, a dapper, mustached Major General Alan Jones addressed his troops from the stage. He had been preceded by the Deputy Commander who announced that the Division was on alert for transfer to a port of embarkation for movement to a theater of combat. Jones was obviously in high spirits, having secured permission from the War Department to take his long suffering Division into combat. As a Regular Army officer he had been in charge of training replacement units for shipping out to plug holes in active Divisions which had sustained major losses in the European Theater of Operations. His command had been levied thusly six times, leaving only a cadre of higher rank officers and men to start all over again the tiresome process of indoctrinating rookies. He was thus in high spirits and ended his challenging remarks with the prediction that his “Golden Lion” Division would “make history”. What sort of history he fortunately could not foresee. In those days the fetish for secrecy had pervaded the entire country, spawning a proliferation of signs everywhere to the effect that “Loose Lips Sink Ships” and the like. In our situation the attitude resulted in an order that all members of the Division were to be restricted to the confines of the Post until the transport trains were boarded. Since my wife had resigned her job in the Transportation Corps in the Battery in New York she accompanied me to the nearby town of Columbus where we had a small apartment. Feeling the need to advise her to depart for her home town in Texas, I promptly broke the restriction and dashed into town with the news of imminent relocation. We hastily devised a code by means of which I could keep her informed about where in Europe I might wind up. This involved mention of various species of birds which might slip by censors and let her know if our movements were to the east or south. This done I made a dash back to camp hoping to slip in without being caught in violation of the orders. On the way to the bus station, as I passed by an alley, a soldier staggered out into the street and collapsed with a knife stuck in his back. Acting with the instinct of a surgeon I knelt down to assess the nature of his wound and soon found myself surrounded by a crowd including several MPs. I recall crawling hurriedly to the edge of the crowd and escaping the somewhat delicate predicament and getting back to base as rapidly as possible. I had no desire to become history in such fashion. The Army has a reputation for moving in fits and starts. But once a decision to move had been made things begin to happen in short order. The Transportation Corps lost no time in getting the troop trains into camp and soon the Division was loaded up and the move to Camp Myles Standish in Massachusetts began before we were really prepared for such a precipitous departure. It began swiftly but there were problems in scheduling such large movements so that our cars were held up in such places as the rail yards at St. Louis where we spent nearly a day of boredom watching the railroad workers clean up the trash which drops from cars jammed full of soldiers. There was one very busy black employee who wandered about with a long scoop, picking up strange objects. When we asked him what he was doing he explained that he was a “turd spotter”. The car toilets bore the customary advice to avoid “flushing while the train is standing in the station”. This injunction could not be observed during such long delays which we experienced on the way east. Leaving behind that engaging problem we then had several days of profound boredom ahead. During the long journey on the Pennsylvania Railroad there were several occasions when fights would break out among the enlisted men and I tried to restore order only to discover that the Sergeants preferred to settle such matters without my interference. It was during those days that Lt. Richard Schaeffer and I were isolated in our car and I tried to get to know him. During the few weeks when we had participated in field trips with our Company B of the 423rd Medical Battalion we had few occasions to become acquainted since neither of us spent nights in the camp. I suppose that we each regarded the unexpected assignment to Infantry as an unjust reward for having signed on as reserve Lieutenants in the Medical Corps during the medical school days. Moreover, we were both plucked from residency status and called to active duty by some sort of lottery selection which apparently did not recognize our progress into specialty fields, his Internal Medicine and mine Surgery. It was not easy to get to know Dick. He kept his own counsel and, more often than not, remained aloof from the men of the Company although he was, by virtue of having an earlier date of rank then mine, technically the commander of the unit. By the time our train unloaded at Myles Standish I still knew little about him. Once installed in our Quonset huts at the Camp we again had few opportunities for developing understanding. He availed himself of every opportunity to secure overnight passes to visit nearby Taunton Green. I, on the other hand, had pitched in to get to know the Company First sergeant and the dozen or so Corpsmen who rounded out the roster of men with whom we would function. In trying to look after their well being I had made the cardinal error of investigating the possible source of a bout of diarrhea which had plagued the troops one week end. Thinking that I had discovered the culprit when I saw cooks in the Camp mess hail tossing salads in forty gallon trash cans, I sought out the permanent party staff of the Camp and advised them of this deviate procedure. My reward was assignment as inspecting officer to check the sanitation in the mess hail for a week. This effectively removed me from the daily business of assembling the Company so that, by the time the Division embarked for Europe I still knew little about Dick or most of the enlisted men of our group. The need for security imposed by the war status imposed a new duty which Dick and I shared and which did give us an opportunity to know some details about the enlisted men of the Company. It was the usually odious task of censoring letters from the men prior to their being cleared through the Division postal section. Each day at mail call each man had to turn over his letters for our scrutiny. For this process we used razor blades to snip out lines containing details of our location and probable future movement. We usually performed this work in late evenings before retiring. In this small duty I got to know Dick a little better but still could not divine his thoughts about the military. His resentment continued to mount and this new work we both found distasteful. So we at least agreed on this one matter. The 589th Field Artillery Battalion had departed for England before the Division reached Camp Myles Standish. The scuttlebutt had it that General Jones had been ordered to send this support group of the 106th as a separate unit . Supposedly he had gone to Washington to get permission to send the rest of the Division. Whatever the truth was, there was a long delay at the Camp before arrangements could be made for our transportation to Europe. At last, late in November, we were again moved, this time to the Boston Port of Embarkation where we were transferred to the U.S.S. General Grant. This ship was formerly the ocean liner Manhattan which, by tearing out cabin walls, had been converted into a troop carrier accommodating several thousand men in two tier bunks. So it was crowded but had the advantage of speed. Cruising at over twenty four knots it made the crossing without destroyer escort. To elude German submarines the ship zig-zagged across by way of the Azores. The course changes were frequent enough that we could see the curving wake astern and imagine that the Captain had sensed trouble ahead and dodged lurking subs. None materialized and we entered the Irish Sea in daylight with the green shores of Ireland on our left. When the ship docked at Liverpool a small brass band dressed like Keystone Cops, derbies and all, played such tunes as Yankee Doodle, supposedly to make American soldiers feel welcome. Most of us were actually watching nervously as the cargo nets hoisted our bedding rolls out of the hold and dumped them on the docks. Occasionally a roll would tumble out and drop into the foul water of the harbor. Each such event brought a groan from our troops since most everyone had stashed away a bottle or two of whiskey in the bedding. The quartermaster would reissue bedding, but not liquor. Dick Schaeffer and I managed to find our rolls and retrieve them from the mountain of identical olive drab canvas rolls. Our bottles were intact so we felt relief in finding our emergency rations had survived the helter skelter of offloading. I still have no idea how our vehicles were transported but, somehow, the personnel and our original equipment all wound up in the neighborhood of Cheltenham in Worcestershire, about 150 miles northwest of London. The “hurry up and wait” phase was beginning all over again. The latrinograms had it that we would be sent to the continent any day but no one had a fix on where or in what role. We again fell into the routine of assembling the Company every morning to receive the report from the First Sergeant that “all men are present or accounted for”. Since it was a simple matter to secure overnight passes I managed to visit my brother who was forecasting contrail conditions at the Eighth Air Force Headquarters at Thetford in The Wash northeast of London. A day at the Air Force field brought the war a little closer as the B-17s were returning from missions with ragged holes in their wings and fuselages. As the bombers were on their fmal approach to landing some would fire rockets to indicate that their crew had sustained casualties and needed ambulances. A brief visit to a squadron briefing room revealed the chalkboard crew assignments. some bearing marks indicating airplanes which had not returned. So this was the war, up close and personal. Back at Cheltenham I discovered that there was a fine exposure of Cretaceous chalk on a hifi just out of town. I collected a hand full of well preserved sea urchin fossils out of expeditions to this site. Otherwise there was little to do but await orders to move out. The censoring of mail continued with greater intensity and more and more strips had to be cut out of letters since most of them revealed our location in Cheltenham, a matter which was viewed as very sensitive by higher authorities. By the end of the stay in England Dick and I had come to know which men were making impossible promises to two women simultaneously. The topics upon which we could agree were thus becoming a little broader and we began to find common bonds in more areas although the association had yet to advance to friendship. The people of Cheltenham were reserved and seemed to tolerate, rather than appreciate, our presence. Perhaps they were weary of the overwhelming number of Yankees who had descended on their island with equipment sufficient to sink it into the sea. We did, however, learn that they held a common belief that Henry VIII had sequestered one of his Royal mistresses in the old castle which housed the Division Headquarters detachment. It was, of course, the appropriation of such facilities which had forced the permanent residents into makeshift accommodations. During the weeks we spent awaiting orders for movement the Division exercises were largely devoted to the learning of such niceties as the “Speedometer Interval”, an equation which would be needed to calculate the distance between successive vehicles in cross-country movement. That, of course, like so many other matters, was only the application of common sense to details which most drivers would observe in everyday life. Of course the statistics dealing with highway accidents served to show that most citizens seem not to factor in such details in their daily life on the highways. At last, in the last week of November, the order to move to the continent came and we were all loaded aboard our intrinsic unit vehicles; for the first time as I recollect. An Infantry Division on the road is a formidable assemblage of prime movers, personnel carriers, trucks and Jeeps. Like a giant caterpillar the mass of machinery and men drifted southward toward the English Channel. The training in proper separation between vehicles paid off so that we made steady progress but had little opportunity for sightseeing before we crossed a hill to see a downward stretch of road leading down to the harbor city of Weymouth. There at the dockside the trucks, tanks, personnel carriers and Jeeps were being swallowed up into LSTs (Landing Ships Tank). These small sturdy craft were leaving in groups of perhaps a dozen at a time to head out into the Channel. Our departure coincided with a change in what had been fair weather at Cheltenham and on the highways south. Once aboard and under weigh we found, to our delight, that these were Naval craft, manned by servicemen rather than the Merchant Marine civilian crew who had treated us like cargo on the USS General Grant on the Atlantic crossing. On the 1ST we were welcome to frequent the officers’ compartments and even the bridge at will. That, of course, is where Schaeffer and I remained during most of the crossing. What with the rough seas and excitement we were making deep inroads on the coffee supply all the way. The Channel that day was very choppy, to say the least. Looking ahead and back along the line of LSTs I recall many times when the masts of the ships ahead and behind would roll until they were misaligned by at least 900. With this degree of roll several tanks in the hold began to shift sideways and finally one of them broke its moorings and slammed into the sidewall of the ship. This precarious situation was frightening but the sailors were accustomed to such problems and soon had tamed the loose object and moored it back in place. After that rough crossing we were glad to at last anchor off the harbor at Le Havre by nightfall. Only then did Dick and I find bunks and turn in for the night. The next day we were again in the “wait” mode as LSTs were cleared for entering the Seine River mouth, At length, late in the afternoon the ships in our area began to weigh anchors in preparation for leaving. There was a commotion on deck which we soon found to be caused by the observation that the LST next to ours had raised, along with its anchor, a huge marine mine about three feet in diameter. It had all its little detonator horns sticking out so represented a serious threat. The commander of the convoy then ordered our 1ST, along with all others in the area, to leave that locality and get clear while the other 1ST crew managed to disengage the threatening object. With that behind us we then started up the river against its flow, proceeding very slowly. As night descended we stood along the rail of the ship as a sailor at the stern kept calling out to the bridge warnings that we were drifting too close to the shore. Thus preoccupied we got little sleep that night and were still a little groggy when we reached Rouen. Fortunately there was another “wait” so that when the Medical Battalion disembarked to be reunited with our vehicles we were rested when we hit the road eastward in the morning light. The passage through France was, again, slow and halting, so that when night was approaching we set up a bivouac camp which was so large that it must have included the whole Division. As the cooks began to prepare a makeshift dinner we fmally saw real French people. They were mostly children who approached us asking for chocolate. They must have been trained to beg such favors from the Americans and at first we did have some small candy bars to quiet their requests. Finally, when they became annoying, I recalled the only French words I knew, the name of a popular perfume back home. So I motioned to them and said “Suivez moi”. This, some smarter soldier told me, meant “Follow me”. And they did; everywhere I went. We finally had to drive them off so we could set up camp. By this time we had passed crossed most of the province of Picardy and stopped for another bivouac in a deeply forested area almost at the border west of Dinant in Belgium. By that time, in the first week of December the legendary worst winter of the century was setting in and the trees were covered with fluffy snow. Pup tents were scattered for miles around, most of them hidden from aerial reconnaissance, we supposed, although we had yet to see any evidence of the combat we knew we’d been “committed” to. The soldiers had built fires from the abundant tree cuttings in this commercial pine forest. Being tenderfoot soldiers they failed to realize that the rising hot air would melt snow. Consequently, their fires were usually snuffed out by the falling avalanches of wet snow. After the “baptism” by snow the Division was once again on the road and in short order entered the town of St. Vith. Here General Jones had set up his headquarters and was being briefed by Major General Walter M. Robertson on the disposition of the units of the Second Infantry Division which we were to replace in the line. Major Edwin Neigus was moving in with the headquarters detachment of our 33 1st Medical Battalion and the Clearing Company, Once settled in he then ordered our Collecting Company to move to its position in the front line to replace the equivalent unit of the Second Division near the village of Buchet where we were to support Colonel Charles Cavender’s 423rd Infantry Regiment. We were not in our combat attire but had retained the habit of wearing dress uniforms, complete with ties. This had made the troops of the 106th Infantry Division the object of some ridicule by the seasoned Second Division, who were turning over their prepared positions which stretched out along an 18 mile front covering the Ardennes and the Schnee Eiffel. They had been in combat since going into action on Omaha Beach the day after D-Day and were seasoned by the heavy fighting in the Hurtgen Forest. Their commander had seen to it that his troops acquired guns and supplies far exceeding their table of allowances. They had taken all that extra equipment with them as they moved north to attack the Roer River Dams. They had left behind a few of their personnel to show us where we were to be bunked before they, too, departed. So our Infantrymen had log-covered foxholes and the 331st Medical Battalion moved into the farm houses and tent sites which had been prepared by the Second Division’s Medics. We had been assured that the occasional passage of large caliber railroad gun shells was not a cause for alarm and that the nightly flights of Bed-Check Charlie was only a lone German airplane carrying no guns or bombs. We were also advised that German patrols might pass through our unarmed position on reconnaissance missions. When we heard them outside our little house every night we were not so easily calmed by the supposition that they meant us no harm. Less easily dismissed was the clanking and squeaking of heavy machinery in the forests just to our east. When we reported these sounds back to Division we were told that we were imagining these odd sounds or misinterpreting the sound of farmers’ wagons. Our mission was to provide medical support for the 423rd Infantry Regiment but we were within walking distance of their Headquarters in the village of Buchet. That made it hard to acknowledge the supposition that the patrols were not up to anything threatening. The only fixtures which our predecessors had left us were numerous 105mm brass shell casings which were standing at convenient locations within access of sleeping areas in the farm buildings a few hundred yards north of Buchet, which was just on the east side of the border between Belgium and Germany. In Buchet itself were the Headquarters of the 423rd Infantry Regiment for whose troops we were to provide our services. 1st Lt. Dick Schaeffer and I were the only officers in the Company and thus occupied a room on the second floor of the house. On the evening of 15 December, 1944, we had settled into a routine of playing gin rummy with our First Sergeant, a veteran of the long months he had spent with the 106th Infantry at Camp Atterbury in Indiana. By mid December we had come to appreciate the utility of the large brass casings since in the long hours of darkness of those winter nights we had become reluctant to leave our buildings to visit the outdoor latrines. This state of mind had been engendered by anxiety which grew progressively as we heard the guttural voices of German patrols who infiltrated our lines every night. Being young we had not lost the urination skill which was required to score direct hits on the open tops of the upright shell cases. So, that night we had put aside worries about the creaking and ratting sounds to our east. Division Headquarters had told us that these were figments of our imagination so we had elected to retire for the night and make our last contribution to the cylinders which, during long nights, accumulated considerable weight, thus making them relatively stable. Bedding down had become a burdensome chore. The now familiar ultra-light camper’s sleeping bag was not, to my knowledge, even available on the market; certainly not to the Quartermaster General. We were supplied with “bedding rolls”, heavy flat canvas bags into which we rolled up the familiar olive drab wool blankets. Getting into these tombs required the patience and agility of a ferret. Getting out was less demanding as a rule. But it took patience. Chapter 2 The Longest Day At 05:30 the morning of the 16th what was later characterized as the heaviest artillery barrage of the whole war erupted around our position. Schaeffer and I jumped to our feet and performed an acrobatic clumsy hopping act trying to escape what we called then our “fart sacks”. The makeshift artillery urinals were kicked over and thus we spent the rest of the morning with damp socks in our combat boots. We managed to get into our quasi dress uniforms, however not putting on the neckties which had been the object of ridicule by our Second Division predecessors. We were thusly attired as we rushed to pull aside the blankets which kept the window at the east end of the room in blackout. The fireworks we saw would have been appropriate for the Fourth of July. But this was midwinter in Germany, and there was nothing to celebrate. The tracer bullets of machine gun fire crisscrossed the scene as far as we could see; from the south, where the 28th Division was deployed, to the north where our 423rd Regiment was stretched out into a thin line covering some four miles before the 14th Cavalry took over. Even more awesome were the parallel trails created by the missiles fired by batteries of “Screaming Meemies”. These were the Nebelwerfer multi-barrel rocket launchers, which were not only spectacular but creating ghostly wails as they flew. Most of these tracers were apparently arching over our lines toward some targets to our right rear. Dominating the scene however, were the brilliant cannon flashes followed by the whine of their projectiles which, again, were over flying our position. By the time the men of the Company had assembled outside our building we were well aware that we were under fire; “baptized” as they say. As we analyzed the pattern of tracers, however, it was apparent that the heaviest action was to the south and north of our Collecting Station. Obviously the patrols we had heard had kept the attacking Reichswehr commanders advised of the location of the least likely resistance, and the Red Cross insignia on our uniforms and vehicles had identified us as unarmed. The attack was thus bypassing our position and the battle erupted south and north of our station. Dick Schaeffer, through our First Sergeant, set in motion the preparation of the operating room for handling casualties. While Dick and I watched the fireworks the corpsmen assembled the instruments, set up the operating tables and portable X-ray machine, and we were ready for business. The month or so of training at Camp Atterbury had, despite the sloppy field exercises we had been through, readied the medics for setting up a MASH-like scene. As yet, though, there was no humor. Years later, in reading Winston Churchill’s writings I ran across his statement that “Nothing in life is so exhilarating as to be shot at without result.” We had been shot at but, so far, there had been no “result”. In fact, as I tried to understand our situation, I began to realize that we had been “committed” to battle, but were not yet in the thick of it. While awaiting contact with Regimental HQ, Dick and I began to see frequent passage of guided missiles flying over beneath the cloud cover. These were the infamous V-i “buzz” bombs which had been wreaking havoc in London. They were close enough to our site that we could see the stubby little wings and the flashes of light which occurred as the fuel detonations propelled the craft toward the northwest in the direction of St. Vith, or so I thought. Many years later I read that most of them were aimed at Antwerp. In any event, as long as their devilish putt-putt eructation’s were audible and the engine had not been shut off to initiate the steep dive toward the target, there was no danger of being damaged by them in our forward position. As dawn began to provide enough light I could hear that the methodical succession of “whump” explosions which were made by mortar shells impacting along the road toward Buchet where Col. Charles Cavender had his command post of the 423rd. By first light the German attack was beginning in earnest. Our Company’s ambulance engines were started to warm them up in the severe cold of the night. I was still fascinated by the fireworks when litter bearers from the nearest Battalion Aid Stations began to arrive at intervals. These first casualties were infantrymen with shell fragment injuries which required only minimal dressing before they were loaded into our ambulances, as many as eight at a time, for transport back to the Division Clearing Company whose function was to stabilize the more seriously wounded for later movement to Field Hospitals to the rear. It was our job to attend to readily controllable bleeding and administer morphine as needed. Each soldier with a wound was first seen by a battalion surgeon who initiated the Field Medical Tag, a card about 3” by 5”, on which was written a tentative diagnosis and a record of when and how much sedation had been administered. To this abbreviated record we added whatever we had done so that in the later chain of evacuation the attending surgeons could avoid over dosage with morphine or repeat procedures which had already been performed. The concept of placing surgeons so far forward in battle zones had been advocated by Harvard’s Dr. Elliott Cutler who, along with Dr. Robert Zollinger had been consulted by the Allied Command in preparation for the invasion of Europe. It was their belief that in the fluid combat situations of World War II that surgeons were needed that close for a number of reasons. In the first place wounds could be treated definitively and often so successfully that some soldiers could be returned to combat duty. Their second object was to clear the battlefield of wounded to keep them out of sight of those who continued to fight. Thus morale could be improved by having the troops know that if they sustained wounds they would receive immediate attention. Moreover, the presence of wounded companions would instill fear in those still fighting. The first more extensive injury encountered that day was a soldier with a dressing on his ankle and another on his groin. His tag revealed that bleeding from the ankle wound had been stopped by cutting into the site of the femoral artery and actually tying it off with ligature of catgut. This action at the Station was about as stupid as could have been carried out by the least experienced intern, for it cut off the principal blood supply to the entire limb. A simple pressure dressing and elevation of the leg would have diminished the ankle bleeding until, in the Collecting Company, we could have extended the wound enough to access the tibial artery. I made a mental note to admonish the Battalion surgeon. But before this became possible a later casualty informed us that the Aid Station had taken a round of incoming artillery and the young doctor had been killed. By afternoon the din of battle escalated to the right of our position and must have involved the penetration of our lines by German troops, for we received our first enemy wounded. One was an infantryman with a bleeding thigh wound and, unaccountably, he was only semiconscious and unable to speak. The corpsmen went about cutting his trouser leg to access the thigh wound when the man began frantically to point at his trouser pocket where there was a strange bulge. One of our minimally wounded infantrymen immediately diagnosed the situation and carefully extracted a potato-masher hand grenade with its pin pulled and its handle held down by the tight trouser pocket. He calmly took the thing outside and lobbed it into a clear area where it exploded into fragments which, had it gone off in our room, would have done serious damage. With a dressing over the leg wound our curiosity then shifted to the mental problem. At first there were no obvious head wounds but for a small entrance hole above the left eye, but no exit wound. So, the first use of the portable X-ray apparatus revealed a bullet in the posterior cranial fossa apparently lying over the cerebellum. After lot of speculation it was concluded that the round had only enough velocity to enter the orbit and glance off the underside of the skull to be deflected along a superficial route to the rear without exiting, but doing enough damage to the cerebrum to account for the soldier’s inability to speak. By afternoon we had dispatched the last of our three ambulances to St. Vith and none had returned. The first attempt to use the telephone to call the division headquarters yielded contact with some Cavalry unit down near Bleialf who reported that they had been unable to call out at all. It dawned on us then that the patrols we had been hearing in the nights before the outbreak of shooting had actually been rerouting the lines which had been rigged by the Second Division. So we were incommunicado. We then sent our liaison Sergeant off in the direction of Buchet to contact Col. Cavender’s Headquarters for instructions. He returned after a few minutes to report that “there’s nothing there but Germans”. Dick and I, being thus in the dark, hastily considered our situation. With casualties having slowed down to a trickle and with no ambulances to take any of them back, it was concluded that we had best relocate toward SchOnberg (“relocate” being the militarily correct euphemism for “retreat”). As I recall it, there were no objections to this hasty decision, although we had no idea of what we would encounter on the way. While the corpsmen loaded the few remaining casualties into the two 2 1/2 ton trucks Dick I and donned our field jackets. We picked up toilet articles, and crammed them into the little gas mask bags which had been emptied of their intended cargo. I also grabbed a 35mm camera and a pair of binoculars which had been brought along in the hope of identifying the European birds. Everything else was jettisoned. Thus the letter I had intended to mail to Betty to assure her that I had not forgot that the 16th was her birthday, along with the lovely sea urchin fossils I had collected weeks before in England, were left for the amusement of the Germans, who I was sure were not far behind. Although Dick was technically in command it turned out that I was ,the only competent map reader so led the way north toward Oberlascheid. Along this stretch of the secondary road we passed several isolated infantrymen of the 106th who were crouched behind trees seemingly awaiting targets to materialize from the east. I took this to mean that we had, indeed, been left beyond the front line. There was only occasional close small arms fire until after we turned west to pass Radscheid and the western end of what became known later as “Skyline Drive”. To reach Schonberg we then had to negotiate a log road to the main secondary road running from Buchet to Schonberg. This rough narrow trail was known as the Engineer Cutoff. About half way down this road machine gun fire was rattling up and down a small gully which was probably a tributary of Ihren Creek. With great presence (or absence) of mind I placed my steel helmet over my knees, figuring that knees were more sensitive to pain than scalps. After a pause to consider the risk of heading back to the east I took the two lead Jeeps and a quarter ton truck across the gully. The first 2 1/2 ton truck with a few casualties aboard tried to follow but became mired in mushy frozen creek bed until one of the men had the courage and presence mind to unwind the steel cable from the winch on the front bumper and attach it to a tree on our side of the creek. Thus he winched the 2 1/2 out and away from the track of the gunfire. This left Schaeffer and the other vehicles containing most of the corpsmen and the other 2 1/2 ton truck with some casualties aboard with a dilemma. He shouted back that he was going to retrace his route and try another way out. So our small group continued up the Schonberg road going north. I never saw Dick again, but heard later, in our first prison camp, that he and the other half of the Company had been captured and detained in a camp where he was killed in a bombing raid. I have never been able to confirm that rumor. Reaching the end of the Engineer cutoff, our vehicles then raced north toward Schonberg but encountered a German anti-tank unit a half mile up the road. Since there were two 2 1 / 2 ton trucks lying in ruins on the left side of the road I assumed that we had reached the end the run. The Germans, astoundingly, came to their feet and waved us on, apparently respecting the Red Cross insignia on the side of the vehicles and on our arm bands. At that point we felt sure that we had been left behind by the 423’d and were lucky to have made our way through the lines and were back on “our” side. Another mile up the road, however, we came under artillery fire. Since it was coming from the direction of St. Vith we wondered whose guns were shooting at us. That was not the important thing so we all bailed out of the vehicles and took cover in the shallow roadside ditch. The shelling ceased after a few rounds leaving one Jeep damaged. So we drove the remaining Jeep and the trucks over to a nest of farmhouses on a hill overlooking the village of Schonberg. The buildings appeared to be unoccupied but for a lone farmer carrying buckets to a barn near the main house. It had been a policy to evacuate farm villages in combat areas so this shelter must have been taken over by our own troops who had established the positions inside Germany which we had just vacated . So we unloaded the litters and the few seriously wounded patients, including the German soldier with the head wound. We still had a small supply of morphine so eased the discomfort of several casualties before trying to establish a shelter for our small contingent. There were only a dozen of us who had made our way through the hail of fire back at the crossing at the creek on Engineer Cutoff, so we prepared for the night in two of the buildings where we broke out the C-rations someone had thought to load aboard the larger truck. The sounds of battle were getting closer so we prepared wood fires in the fireplaces in the houses and tried to settle in for the night wondering what sort of predicament we were in. An hour or so after dark we found out. The chilling sound of “burp” guns approached from the east, clearly something we had never heard at close range before. Those rapid-fire portable machine guns were the ancestors of the AK 47. They fired bursts of eight or more bullets in a fraction of a second and were in good supply in the Wehrmacht. So much for sleep. The matter was settled in a few seconds. A rifle butt knocked out the window under which several of us were sitting and a command, in English, advised us to come out with our hands raised. I was in no mood to disobey an order backed up with that sort of firepower. The leader of the small group of Volksgrenadiers read us the Geneva Conference equivalent of the Miranda clause. He spoke fluent English, advising that, as Medics, we would be considered “Internees” and not prisoners in the conventional sense. Small comfort. So , in an hour or so short of a full day into our career as combat medics we had “relocated” to escape impending capture and had been apprehended in a not very heroic surrender. Before we departed Camp Atterbury in Indiana for our journey to Europe, General Jones had told the assembled division that the 106th would “make history”. And our small group went into history as a lost unit unaccounted for in the early analysis of the beginning of the Battle of the Bulge. Much later, in reading accounts of Winston Churchill’s exploits as a newspaper correspondent during the Boer War, I learned that, in commenting on his surrender to the Boers, he recalled a quotation from Napoleon to the effect that “When one is alone and unarmed, a surrender may be pardoned.” So, we were indeed unarmed and apparently alone. We were not long alone. The four German infantrymen who had secured our capture must have been from the 18th Volksgrenadier Division, which was an arm of the Fifth Panzer Army. They were not as Volksy as their name implied, these adjunct soldiers of the famed and feared Panzers. As soon as they had lined us up against the wall near the window they had smashed they immediately added wood to the fire, removed their boots and socks and carefully dried skin and foot gear. I recall thinking at the time that more American soldiers in that sector had suffered from frostbite than from wounds. Not these experienced soldiers. Having dried their feet they then cleaned and oiled their weapons. Not until those necessities had been accomplished did they eat. Their field rations were individually packed. Each man had a loaf of heavy bread and a substantial wurst about a foot long. So all they had to do was slice off what they wanted and they were ready for as much sleep as they could manage before moving on. By dawn the Grenadiers had departed, leaving us with some gruff advice to stay put. Since the sounds of battle were getting closer I could imagine no sound alternative. The few casualties we had managed to bring with us were in good condition but for the still sedated or barely conscious German infantryman. Taking stock of our supplies we again resorted to the remaining C-rations and had a breakfast of sorts while watching the road junction where we had been shelled. It soon became apparent that the fighting was mostly to our south, the direction from which we had gained access to Schonberg. As we tried to assess the situation we became suspicious of the white objects which were along the crest of the hill to our south. The German troops we had seen were wearing white camouflage coats so when more such objects were spotted they became soldiers when, in fact, most of them turned out to be porcelain insulators on the power lines. As this jittery frame of mind was put to rest and we were alone again yet another unit of Germans came down from the road junction and turned off to our little group of farm houses. I still have no idea who they were but they immediately began to take over the Jeeps and trucks and seemed to recognize that we were unarmed medical personnel. While the enlisted men amused themselves trying to learn to operate Jeeps their officers kept annoying me with repeated ‘Warum”(why?) questions. What they couldn’t understand was why the Americans were fighting the very people who were trying to save the world from the Russians. In the nearly ten years since I almost flunked German at Rice University I had still not become comfortable with trying to use a language where the verb always comes last. That, plus the fact that I was not in a very strong position from which to argue, left the issue unsettled. Even more uncomfortable was the steady approach of battle to the road junction where we had been shelled. Artillery fire which seemed to be aimed just beyond our hill in both directions was intensifying. The weird warbling whine of 88mm shells was particularly unnerving. These cannon, which were originally designed as anti-aircraft weapons, threw high velocity shells which wavered in flight resulting in a pitch ossification which some Quartermaster troops had told us sounded like “you ain’t a’goin’ back to AlaBAAAMMM!”. There was a saving grace in their swoosh; if the round was going wide the Doppler effect lowered the pitch of the wail as it passed to one side, If it only became louder it was prudent to duck. The German unit which had stopped for a few hours to argue went on about their business, which was apparently part of the effort to take Schonberg. As that battle escalated I began to observe the behavior of the enlisted men who accompanied the First Sergeant and me from Buchet. The most memorable of them was a corporal whose mail I had been compelled to censor, a very distasteful duty which was required of all officers. His many letters had been directed toward two women, one his wife. In addition to the very gaudy and explicit sexually oriented paragraphs he always inserted another in which he promised each lady a vine-covered cottage after the war. It had occurred to me that his only escape from that impossible dilemma would be to expose himself to all the incoming fire available. Instead, he crawled behind the iron wood stove, calling for me to make it known that it was against the Geneva code to fire on unarmed medics. Since there were no Germans in shouting distance his argument was ridiculous, at best. The other fixed memory is of the very young and tidy private whose letters had all been to his mother. He was meticulous in dress and manner, which was probably why he was appointed our Company Clerk. While the rest of us ducked approaching shells this lad pulled his pants cuffs up above his combat boots to keep from soiling them as he stepped gingerly between the slushy snow patches. The rest of us ran directly from one cover to the next. During that afternoon, before the small arms fire erupted around our hifi, an American Artillery Lieutenant materialized at our position on the run from action nearby. He was trying, he said, to get back to St. Vith and had spotted us as he worked his way around Schonberg. Despite my suggestion that he remain in our probably safe location, he took off to sneak through the woods south of town. Later, when the rifles and machine guns got closer, I wondered if he ever made it back. Forty years later, in MacDonald’s A Time for ,Trumpets, I would read that he was either Harold McKinley or Ivan Long and that he did make it back. The night of the 17th remains a shade vague in memory. The battle sounds now included close small arms fire, particularly the dreadful rattle of the Burp guns which fired brief bursts of six or eight rounds in rapid succession. I have no idea where either side was located that evening, but we were on the receiving end of rounds entering the windows. The exchanges were clearly taking place down in the valley where Schonberg was situated, about a half mile west of our hilltop ringside seat. But I could not actually see the village itself. The topography was not clarified in my mind until 1963 when I found the place just as I remembered it. The hilltop houses were the same and they could not be seen from the village. How we occupied ourselves that night I can not imagine, but it was probably trying to justify our erratic flight from a heavy combat situation. I do remember clearly that my own concern was with the notion that Col. Cavender had retreated (or “relocated” to the rear) without informing his supporting Collecting Company. The other alternative was that we had beat a cowardly retreat rather than relocate in the direction of the most audible battle sounds. Neither alternative explanation was very comforting. In the few remaining hours of that night, while alone again, I worried about the interpretation higher command would make of the hasty relocation. Dick and I made our own decision to get back to St. Vith but now I was solely responsible for the serious situation. In trying to construct a credible explanation I kept remembering something my high school English teacher had said when I tried to forge an explanation for not having completed an assignment. Kathleen Witherspoon guided her classes through literature and my brother and I loved her and respected her authority. Our vocabularies were expanding exponentially under her tutelage. But, on hearing my lame excuse she said that I was “clandestine”. I had a general idea of what the word meant. But after school I hastily consulted the dictionary to find that she implied that I had told a lie to deceive her. So, in the untenable situation I found myself in, I wondered if the excuses I was trying to construct would be considered “clandestine”. I still do. Early the next morning two officers wearing medical ornaments came to the hill and, in reasonably functional English, asked if I would join them at their Hauptverbandplatz in the village. On the condition that they would accommodate our few wounded this proposition was eagerly accepted and we were then joined by Michael E.. Connelly, a Battalion Surgeon from the nearby 589th Artillery Battalion which had been supporting the Division and had been rounded up in the sweep up from Bleialf to Schoenberg. They were huddled behind barbed wire and watched as we wandered, unfettered, talking to the German officers. They obviously did not understand how we were not with them behind the wire fence. When Mike and I recognized the Brigadier General who had commanded the Artillery battalion we averted our gaze and, tried to avoid his unbelieving stare. After running this gauntlet we entered the German equivalent of a Clearing Company, which, we were told was designated the Hauptverbandplatz. There we were joined there by Lewis Myers and John Martin who had been recruited by the same team of German medical officers. The prisoners we had walked past on the way down to the Hauptverbandplatz were probably mostly from the 589th Field Artillery who had been in intense action south of Schonberg before being rounded up in small groups. Colonel Cavender’s mass surrender, I was to learn forty years later, had held out until the afternoon of 19 December when he reluctantly surrendered. Along with him was the son of General Alan Jones, the Division Commander. All in all the 106th lost 6,879 men as prisoners. Again, this knowledge came decades later, so was acquired long after the doubts about the valor or my retreat had been suppressed by later events. Chapter 3 The Hauptverbandplatz There were three surgeons in the Hauptverbandplatz. One of them, Sigmund, spoke some English. It was through him that we became integrated into a team which worked day and night handling the masses of wounded soldiers. On the following day we were joined by an Oberartz Dresen who was the senior surgeon. We also had the help of a very young German medic, Kurt Rettig, who had acquired English in school and served as our translator for most of the conversations with the other members of the team. The structure of the Hauptverbandplatz (or “Head Bandaging Place” ), was similar to the plan our armed forces developed for management of battle casualties. One officer was assigned to triage and so worked through the several hundred wounded soldiers lying on the floor of a barn adjacent to the operating room. Since John Martin didn’t have the stomach for surgery he joined the triage team and we rarely saw him during the workdays. They would send in, for definitive treatment, those whose wounds appeared to be survivable. Judging from the almost constant moaning, to which we never grew accustomed, many of the wounded must have been beyond salvation. Only once did I find the time to look into the adjacent triage barn and saw the casualties, a hundred or more, lying in rows with the triage team checking them methodically. Both the American and German soldiers were bearing up silently but many of the most seriously wounded were moaning and calling for help. I did see some bodies carried out on stretchers to be loaded into trucks, presumably to be hauled to the rear. Others with wounds which must have been beyond the capacity of the Verbandplatz were carried to ambulances and probably evacuated to a definitive treatment facility. Their destination was never explained to us, however. With Kurt translating, Sigmund, Mike and I became reasonably efficient functioning team. We worked constantly, taking brief naps on the floor when fatigue became overwhelming. We would awaken, startled, each time the almost constant artillery thunder ceased. This phenomenon was mentioned often in Erich Maria Remarque’s “All Quiet on the Western Front” as a puzzling aspect of life during the trench warfare of the First World War. Of course, then it meant that the artillery barrage had been stopped as one side or the other was emerging from the trenches to assault the other. Since I had read that work, the concept of war which I had come to expect was influenced by that engaging book. At first the casualties were mostly American and, of those, the majority wore red “Bloody Bucket” shoulder patches of the 28th Division which had been engaged on the right flank of the 106th and must have sustained the brunt of the German offensive in those early days of the Bulge operation. The operating teams were oblivious of the nationality of their patients. I still think that we were all more dedicated to Hippocratic than to political codes of behavior. Sigmund, however, made one astute observation which was perhaps indicative of a less humanitarian attitude. He reminded us of our obligation to treat German casualties in the same spirit if the tide of battle should change. And It soon seemed to be going that way when, after the first few days, the majority of wounded were German. One of the early American wounded men who passed through the station was Captain Jim Cagle who Mike knew quite well since he had been the Commanding Officer of the 589th Service Battery. He had sustained a shell fragment wound of the hip but was not seriously disabled. In fact, Sigmund and I debrided and dressed the wound without even using the Evipal general anesthetic. We worked with the same dedication whether the patients wore gray or olive drab. Most of the wounded had sustained bullet or shell fragment penetrations which did not involve bone or vital organs. These we labeled, on their field medical tags, as “durchsplitter “auf’ if the “split” passed through, or “zum” if there was only an entrance wound. The “zums” were handily dispatched by taking out the offending metal in the tradition of the Western movies where the victim was revived instantly on removal of the bullet. It wasn’t that simple of course. In many of the wounds there was deep bleeding from arterial cuts and when such cases came to our attention we would try to induce brief anesthesia by intravenous Evipal use, that being the equivalent of our Sodium Pentothal. Evipal was used in the many amputations which were more freely employed than I would have thought necessary back at Columbia-Presbyterian Hospital where I received my surgical training. I have come to realize, on the other hand, that we hardly ever saw gunshot wounds in Vanderbilt Clinic Emergency Room in the early forties, strange as that may sound to New Yorkers in the nineties. But, there in the heat of a very large battle, we must have treated hundreds of such wounds during the five days we served there. There were several cases which made a more indelible impression. One of them was a German officer with a chest wound which had been sutured together in a more forward treatment facility. Since he obviously had also sustained a puncture of the lung he was in extremis from collapse of the lung due to accumulation of air in the rib cage. I then recalled a trick devised by Evarts Graham during the first World War. This consisted of inserting a catheter into the chest with a butterfly valve on its outer end. This was jury-rigged out of a finger from a rubber glove with both ends open so that when the man exhaled air would go out through the glove. With negative pressure during inhalation the latex glove would collapse and prevent return of air to the chest cavity. The lung would then re-expand and function normally. After this demonstration Sigmund and the Oberartz had a much better opinion of my abilities and they assigned more difficult cases to Lew Myers and me, now that Lew had shown that he was a very competent assistant. He, in fact, probably worked longer hours than I did since he often assisted Mike Connely when he and his German counterpart were taking turns at the operating table. Since we worked in shifts, resting briefly every few hours, one or the other of us was always at the operating table for the four days of the intense battle activity. Another memorable case was that of a young German infantryman who was told that his leg would have to be amputated. Just as the technician was beginning the injection of Evipal he raised his right arm and shouted ”Heil Hitler”. That salute had been observed frequently when we were up on the hill but not around the Verbandplatz. The number of amputations was alarming, and often when we would take short naps on the floor there would be grisly extremity trophies right beside us. There were other memorable amputations but the one which sticks in memory was a German soldier with an incomplete shattering of his leg above the knee who hopped into the room and mounted the table without much help. Sigmund turned to Mike and me and remarked that this was a good example of the bravery of the Wehrmacht troops. Of course this was an impressive display of courage, but the facet of the incident which made the most indelible impression was his youth. He could have been no more than 16 years old.

Late in the afternoon of 17 December cannon fire broke out in the streets of Schonberg within a block of our location. Suddenly a huge Tiger Tank nosed around the corner next to the casualty barn and fired its awesome 88mm gun up the street outside our door. About that time a German officer staggered into the operating room on the stumps of legs which had been blown off at the ankles. He was hurriedly placed on the table and the amputations cleaned up and the stumps dressed. A Few minutes later four haggard and scared American soldiers were dragged into the room and lined up against the wall. They told Mike and me that they were from a small anti-tank outfit who had been told that Schonberg was “lightly held” and had been ordered to attack the small group of defenders. They all groused that “old Bag Lunch” had no idea of what was going on. Of course, no one else did either, least of all our own team. This incident was further evidence of the magnitude of the communications breakdown which had afflicted our own units in the beginning of the battle.

There were many cases which could have been salvaged by blood transfusions if we had possessed even the crudest facilities. Since each soldier’s blood type was imprinted on his “dog tag’ matching donors and recipients would have been simple. There was one American officer with a shoulder wound which had severed an artery which had finally been accessed and ligated just as it was apparent that he was slipping into hemorrhagic shock. Since he was a blood type “O”, and therefore a “universal recipient”, if we had available large syringes we could have chosen any donor and rapidly pumped blood to save him. This sort of transfusion did not require banked blood but could be carried out in any location where donor and patient could be located near enough to each other for what we had called “multiple syringe” transfusions. But there were no large barreled syringes available and the man exsanguinated.

In a lighter vein, I also recall one German soldier with a penile wound which, on inspection, turned out to have been inflicted by a small caliber bullet which must have been a missile which had passed through another victim and lost most of its velocity so did little damage to his most precious possession. This case was unforgettable for another reason: above the pubic hair patch he had a tattoo which read “Nür für damen”” (for women only). We patched up the pitiful organ and wished him well. It was ironic that we did not have any of the “sulfa” drugs available in the German medical installations. The antibacterial action of these compounds had been discovered by a German dye chemist, Domagk, but was not synxhesized in quantity except in England and the United States. Domagk, in fact was compelled by the Nazi regime to refuse to accept a Nobel Prize offer in 1939, the year the Germans attacked Poland. During my years at Columbia-Presbyterian we had been demonstrating that they were of considerable value in preventing contaminated wounds from becoming infected. The German surgeons used, instead, a flavine dye, Acriflavine, in some open wounds. At least they had the good sense not to suture battlefield wounds, but to pack them lightly with ersatz paper dressings. Amputations stumps were always left with long skin flaps and merely dressed with rubber drains to prevent accumulation of contaminated blood, as they should always be. This, then, was standard practice in both armies. During the six days of the operation of the Volksgrenadier “bandaging place” Kurt Rettig had kept us warned that a tall Nordic officer with the dreaded zigzag SS on his coat lapel was planted there to report on any non-Nazi sentiments he could overhear. Sigmund and the others always became silent when he was around so we all regarded him as not trustworthy. As the flow of casualties thinned out on the third day this “Siegfried”, as we called him, motioned to Mike and me to follow him to his room. There he had a small radio which was tuned to the BBC. So here the Gestapo prototype was keeping himself informed while terrorizing the rest of the staff. It was there that we heard that the German offensive had stalled out around Dinant near the French border with Belgium. That was encouraging but still we recalled having passed through Dinant on our progress toward St. Vith. So The front was, at that point, still far to the east. This information somewhat watered down our hopes that we would soon be rescued by a counteroffensive movement. By the afternoon of 23 December the last of the casualties in the triage area had been evacuated by ambulances to the east and we at last had an opportunity to rest and enjoy German field rations prepared by one of their mobile soup kitchens. After the first real meal in a week Sigmund informed us that the next day we would be moved up to St. Vith which had by then been taken by German forces. The next morning we joined in the loading of the vehicles for the relocation. At first light on 24 December the line of ambulances and trucks of the Hauptverbandplatz moved out of Schonberg and over the hill to the St. Vith road. Here we were greeted by an incredible sight of several miles of dilapidated vehicles ranging all the way from Volkswagens to rumbling trucks which must have been left over from the plundering of civilian transportation equipment for use by the line units. Some of the lumbering wrecks were stalled and were being kicked and cursed by their drivers as though they were stubborn mules’ whereas an American column of that sort would have simply rolled the stalled equipment off to the side and gone on forward, these people simply roped the dead car to the one ahead and towed them ahead more slowly. There were some weird cars with large metal tanks strapped to their sides. Kurt Rettig told us that these were wood-burning devices which generated combustible gas which ran their engines. These clever contraptions represented one of the German engineering feats which had developed other alternative fuels as well. This was another piece of evidence which kept suggesting that the Wehrmacht was nearing the end of its rope. When we arrived in St. Vith in the afternoon the unit set up in the basement of the St. Joseph Kloster, the nunnery which had served as headquarters for the 106th Division before they had been forced out. By this time the sounds of battle had moved on to the north and there were no new casualties arriving. With no specific functions to perform I began to review what had gone before. It occurred to me that Mike and I had actually served more American casualties than we would have had we remained in our exposed locations. After all, our purpose in the military had been to care for the wounded, and we had done that many times over. And with the sounds of artillery receding to the north there appeared little chance that we would soon be liberated by some counteroffensive. So, the only option was to sit it out and wait for whatever might become of us. By mid-afternoon of that Christmas Eve the clouds which had provided cover for the German offensive for nearly a week parted and the town of St. Vith began to come under intensive strafing attack by American fighter planes. They swept past our basement window spewing out shell casings like hail. We felt relatively secure behind the thick stone walls of the Kioster but wondered how anything could survive the storm of fire out there in the town. Trees along the streets were topped as though by lawn mower blades. Mike, being the eternal optimist, wondered if this signaled an Allied effort to retake St. Vith and thus bring about our return to our own side. Before we could speculate on this unlikely prospect some General, who must have been in charge of whatever Wehrmacht unit had taken over our old headquarters building, appeared on the floor to inspect the operation. When he found three American surgeons and the Medical Service Corps officer among the team operating the medical unit he gave orders that we should be removed from the forward position. He explained to us that he did not want to be caught with prisoners in the combat zone. Sigmund understood the problem and turned the solution over to a subordinate who had no idea of how to feed us into the evacuation chain. The only thing he could think of was to transport us back to a unit toward the rear. Thus, as night approached we were driven in the equivalent our 3/4 ton truck over to Schonberg and thence south through Buchet via the same route we had covered on the 16th when fleeing from the front. From Bleialf the truck went east to Prüm, some ten kilometers deeper into Germany. During that ride we had our backs to several 40 gallon petrol drums and when we dismounted our coats had frozen to the drums so that we had to literally break loose from the ice on the cold steel. We were then led into what appeared to be a small headquarters of a service unit. Here, again, we were outside the evacuation route of prisoners and the officer in charge spent hours trying to find out where to send us next. At last, as dawn came we were again placed in another truck to begin a two day journey which has been telescoped into a recurring nightmare every time I try to reconstruct the events which followed. The process of assembling memories into a chronology has been hampered, or abetted, however you want to look at it, by an understanding of the way the mind works when evoking recollections of things past. This has never been more lucidly analyzed than in John Livingston Lowes’ ‘The Road to Xanadu”. In this landmark work, which Peter Medawar considers “worth the sum total of everything else which has been written on creativity by anyone at any time, including Plato”, Lowes examines everything which Coleridge had experienced or read. From this wealth of material, including extensive scouring of all the travel books which were popular in the late eighteenth century, and which are known to have been read by Coleridge, Lowes formulates a theory of the functioning of creative thinking. The striking and puzzling juxtapositions of such contradictory visions as “caves of fire and ice” in the Rime of the Ancient Mariner are shown to have been resurrected from what Lowes calls the “deep well of memory” . He points out that whatever neural connections which are involved in the process of memory are not stored in continuous and orderly files but are pigeon-holed in chains of images which have visual or auditory traces which are similar in content. Thus, when we try to recall incidents in our lives we evoke disappointingly brief recollections of a few seconds’ duration of the tactile experiences but fail completely to evoke images of such things as once familiar faces. Prior to Lowes’ revelations it had commonly been assumed that the startling incongruities in such apparently weird poems such as Kubla Khan were inspired by opium dreams. Not so. Their roots lay in the unraveling of memories dredged up in association chains with words and phrases which were not consciously filed in chronological order. Thus, in recounting these remembrances some are inexorably entangled with memories of other experiences which had a similar context. For example, I recall some of the stories told by the great surgeon and teacher Isadore Ravdin. In one of them he revealed that he had been in one of the surgical teams during the invasion of Italy at the Anzio beachhead when he examined a soldier who presented with anal bleeding. On inspection Ravdin found a finger! In another part of the tent there was a young surgeon who had lost a finger while performing a rectal examination on a casualty when a rifle bullet flew through the tent and struck his hand. This story has always been filed along with the surprising discovery of a bullet in the penis of the German soldier who appeared to have only an assortment of shell fragment wounds. It has been arduous, therefore, to recreate the real chronology of events surrounding our capture and subsequent experiences without inserting facts which have been revealed by historians decades after the events herein recorded. Thus, the problem which caused me the most concern during most of the brief career in Gefangenschaft was the nagging doubt that I had been correct in assuming that Colonel Cavender had actually retreated without informing his supporting medical team. The other most difficult aspect of retelling the story has been the expectation by most listeners that there was some parallel between the operation of the German surgical unit and the adventures so ably recreated in popular television series, MASH. That entertaining story was modeled after the Field Army Surgical Hospital which was headed by an Army Urologist friend of mine, Kryder van Buskirk, who did, in fact, have many of the qualities portrayed by Alan Alda as “Hawkeye”. His unit, which had operated in the Korean War, was reputed to have exemplified van Buskirk’s unquenchable sense of humor, which is a generic quality of most of the urologists I have ever known. He, in fact, was hired as a consultant during the filming and writing of this series. But under the circumstances which prevailed during the Battle of the Bulge, there was neither time nor inclination to find anything humorous in the hectic progress of the battle and our contribution to its action. Chapter 3 Leaving the Front After a week of working with German professional surgeons in an atmosphere of collegiality, doing our best to alleviate the suffering of the wounded soldiers of both sides, it was something of a shock to find ourselves being treated as enemies. The driver of the truck leaving Prum was in a sour frame of mind, probably because he had to divert his attention from attacking the enemy to helping us to get away from the combat zone. But a enlisted man private who rode with us in the bed of pickup truck was thankful that he was going away from the battle area. In fact, he behaved in a more humane manner and even shared with us some of the anise flavored cookies which he had received from home. Those little treats constituted our only Christmas dinner. While negotiating the back roads heading to the north and east we encountered traffic heading west toward the front line. At every intersection there were German military police directing traffic. They were easily recognized by the huge crescent silver or pewter crescent ornaments hanging across their chests. Every time our driver encountered one of them the driver stopped and inquired about the way to the nearest site for disposing of prisoners. I still have no way of knowing where or how far we traveled, but, in studying maps of the region I now think we passed near Losheim, which was the gap in the American defenses where the first penetration of our lines by the Germans occurred. The meandering ride wound up finding an installation which looked like an American Boy Scout campsite, complete with young boys in khaki uniforms lounging on the large porch. The driver left us guarded by the generous soldier while he engaged in some negotiation with what appeared to be the adult leaders of the Scout troop. As the morning progressed he came back with several of the kids and an older Wehrmacht noncommissioned officer who indicated that he was on furlough after long action going all the way back to the Normandy D-Day fighting. He brought along several other prisoners who had managed to elude the mass surrender events which produced the great columns of prisoners we had seen around Schonberg. Our contingent of captives then grew to about a dozen men, including a few Air force crewmen and officers who had parachuted out of disabled planes into areas from which they had tried to elude capture. The guard in charge of the prisoners and the Hitler Jugend trainees with their Scout uniforms and, for this occasion, ancient rifles, formed us into a small column and led us past the nearby village and through what appeared to be a target practice range on the edge of town. As we marched the soldier in charge kept telling the kids about his participation in the fighting around Normandy. When we were negotiating the maze of earthen ridges he told the kids that, during the D-Day action, he had captured many Americans and simply shot them summarily. At first it seemed that this was braggadocio intended to impress the Jugend kids or scare us. Whatever his intentions were, the result as partly both. I was apprehensive, as were others in our group, but Mike Connelly tried to quell our fears and made some progress until I saw him making the sign of the cross. Having been brought up in a Catholic elementary school I knew the Hail Mary prayer, having mumbled it every day along with the pupils who had been baptized, as I had not been. So I could lip-read Mike’s words, especially the “blessed be the fruit of thy womb”. Much later he confided that he had repeatedly mumbled, over and over, to himself the Lord’s prayer. As the group went on past the secluded area of the shooting range, and no violence was evident, we relaxed and went on our way out to the secondary roads around the town. I recall, however, the sense of relief and the memory it evoked of Dostoevsky’s description of his narrow escape from execution. Decades later, in reading Betita Hardings “Phantom Crown”, the thought was revived by her description of the execution of the Emperor Maximilian by the Mexican revolutionaries. As he and one of his Generals were led from their cells to the parade ground they heard a drum roll and Maximilian inquired if that were the “signal for the executions to begin”. General Tomas Mejia replied “I can not say, Sire, this is the first time I am being executed”. In any event, we resumed the long trudge along the roads northward. It is about 60 kilometers from Prüm to Münstereiffel. The truck ride, which began before dawn, probably covered a third of this distance. Since we left the Hitler Jugend camp shortly after sunrise, and daylight at the latitude of the Ardennes in late December lasts only eight hours, we had probably covered another thirty kilometers before we reached the outskirts of Münstereiffel during the long winter twilight when the guards allowed us our second rest break. We were all tired, but oddly the Jugend were the most exhausted. Even the older Wehrmacht guard relaxed his vigilance. We took advantage of the halt to evacuate whatever systems were becoming urgently in need of attention. I found a convenient depression in a roadside ditch, dropped my pants and took aim. Looking down I found to my horror that I had chosen a spot which was preempted by one of the long handled “potato masher” hand grenades. I reconsidered hastily and chose a less threatening target. Then, while the guard was nodding, it occurred to me that I was still carrying a small 35mm Argus. I hastily scooped out a burial place for the camera on the supposition that it would soon be garnered as a trophy by the first formal prisoner handling facility we would encounter. Resuming the march we passed the outskirts of Euskirchen long after dark. By this time the nearly full moon was half way up from the horizon and the sky was clear in the late December night. As I watched the moon I kept thinking that Betty was probably watching it rise back at home and thought somehow that it would be a mirror in which she could see that I was watching her. Back in George Williams’ English Poetry class at Rice I had read that Coleridge, when he was on the Island of Malta, wrote a letter to his sister Sara, who was back in England, in which he expressed the same thought.