|

A DIPLOMATIC

“RENAISSANCE MAN”:

RICHARD B. PARKER

THREE-TIME AMBASSADOR RICHARD PARKER WAS A FOREIGN SERVICE OFFICER

FOR 31 YEARS, AND SINCE RETIREMENT HAS CONTINUED TO WRITE AND TEACH.

LAST MONTH, AFSA HONORED HIM FOR A LIFETIME OF CONTRIBUTIONS TO

AMERICAN DIPLOMACY.

BY STEVEN ALAN HONLEY

On June 24, (2004) Ambassador Richard

Bordeaux Parker received the American Foreign Service Association’s

award for Lifetime Contributions to American Diplomacy, in

recognition of a distinguished 31-year Foreign Service career and

equally impressive academic and scholarly accomplishments.

Being born on July 3, 1923, in the Philippines, where his father was

stationed with the U.S. Army, gave Parker an early, if brief,

exposure to overseas life. But his initial professional goal was to

become a chemical engineer. It was while he was studying engineering

at Kansas State University (known then as Kansas State College of

Agriculture and Applied Science) that fate stepped in for the first

time. The future ambassador had to take German as a prerequisite for

chemical engineering, he recalls, “and it was clear that German came

much easier to me than to anyone else in the class. I discovered a

gift for languages that I hadn't realized I had.”

Then fate nudged him once again — much more strongly, this time —

when World War II interrupted his studies and he went overseas as an

infantry officer. Captured by the Germans after the Battle of the

Bulge, he was eventually repatriated at the end of the war via

Odessa, the Turkish Straits, Port Said and Naples. That first

encounter with the “great wide world” left him determined to go back

and see a lot more of it.

Soon after he joined the Foreign Service in 1949, his facility in

languages steered him toward a specialization in the Arab world. In

1961, he became the first non-native speaker in the Service to

attain a 4/4 rating in Arabic, indicating full fluency in the spoken

and written language, from the Foreign Service Institute. That

facility paved the way for him to be a three-time ambassador, to

Algeria, Lebanon and Morocco; earlier assignments included

Australia, Israel, Jordan and Egypt, as well as several stints on

country desks back in Washington.

Somehow, along the way he found the time to take up the study of

Islamic architecture as a hobby and to write two “practical guides”

on the subject — the first of seven books he has written or edited:

Guide to Islamic Monuments in Cairo (American University in Cairo

Press, 1974; now in its fifth edition) and Guide to Islamic

Monuments in Morocco (self-published, 1981); North Africa: Regional

Tensions and Strategic Concerns (Praeger, 1984; a Council on Foreign

Relations book); The Politics of Miscalculation in the Middle East

(Indiana University Press, 1993); The Six-Day War: A Retrospective

(editor; University Press of Florida, 1996); The October War: A

Retrospective (editor; University Press of Florida, 2001); and his

latest, Uncle Sam in Barbary: A Diplomatic History (University Press

of Florida, 2004; see p. 71 for a review). He has also served as

editor of the Middle East Journal, and has contributed dozens of

articles and book reviews to various periodicals.

Upon retirement from the Service in 1981, Parker became

diplomat-in-residence at the University of Virginia for two years,

and has also taught at several other colleges and universities. He

served as the first president of the Association for Diplomatic

Studies and Training and is also a member of many other prestigious

organizations, including the Advisory Council on Near East Studies

at Princeton University, the American Academy of Diplomacy, the

Council on Foreign Relations, the Middle East Institute, the Cosmos

Club and Delta Tau Delta. His many honors and awards include the

Department of State Superior Service Award (1967, for a rescue

mission to Yemen), the Grand Cordon of the Order of the Cedars,

Lebanon (1979); the Air Force Medal of Merit (1980); and the Foreign

Service Cup (1989).

Little wonder, then, that many of Parker’s peers in the Foreign

Service over the years (even those who did not already know of his

penchant for chemistry and math) have described him as a

“Renaissance man.”

Foreign Service Journal Editor Steven Alan Honley interviewed Parker

at his Georgetown home on March 31.

FSJ: Congratulations on your award for lifetime contributions to

American diplomacy, which places you in the same company as George

Shultz, Tom Pickering, Cyrus Vance, George Bush Sr., and Larry

Eagleburger, among others. What would you say have been your

strengths as a diplomat?

RP: I think the fact that I’ve been able to maintain my sense of

humor through some difficult times, first of all. Eisenhower once

said, “Always take your job, but never yourself, seriously.” But of

course, if you don’t take yourself seriously, no one else will,

either. So you have to find some compromise there. But the important

thing is if you don’t take yourself too seriously, you can

understand the humor in the situation in which you find yourself and

you can relate much more easily to other people.

I would also say that I’ve always concentrated on doing whatever my

job was to the best of my ability.

|

“The

term ‘Arabist’ was no compliment even in the 1950s, but

it was a fascinating world and language. And no one ever

tried to warn me off from going into it.”

— Richard Parker |

FSJ: You were born in the

Philippines. How long did you live there?

RP: We left when I was three months old. My father was stationed

there as an Army officer; and they were just waiting for me to be

born.

FSJ: I understand you originally planned to be a chemical engineer.

What drew you to the Foreign Service instead?

RP: Well, engineering studies are very difficult, with a very heavy

class load. The war was on, and I had sort of lost interest. I had

one more semester to go at Kansas State College of Agriculture and

Applied Science (now Kansas State University), before I was going to

be taken into the Army in 1943, and I said the hell with it, I’m

going to have one fun semester before I leave. So I dropped

engineering, much to the dismay of my faculty adviser, and took a

semester of things like public speaking and Spanish, as well as

German, which I’d already been studying — that was required for

chemical engineers — and navigation math, which was very easy. That

made 12 hours of

very easy courses. So I had a wonderful semester and a great time.

FSJ: This was the fall of 1943? RP: The spring.

FSJ: And you were already in officer training by this point?

RP: Yes, I was in ROTC. We were told we would be sent to an OCS

(Officer Candidate School) after we did our basic training. I was in

coast artillery, or anti-aircraft, ROTC as befitting an engineer,

but along with all my classmates, ended up being sent to infantry

OCS — which, of course, was a good deal more dangerous.

FSJ: And then you shipped over-seas in 1944?

RP: Yes, our division went first to England and then to France.

FSJ: Tell me about your experience as a POW in World War II.

RP: Well, our division was annihilated in the Battle of the Bulge,

and I was among the thousands of men captured. I spent only 34 days

under German control, ending up at a camp for American ground-force

officers in Poland, near Poznan. When the Soviets finally began

moving west from Warsaw, where they’d been stopped the previous

September, the Germans started marching us back to Germany. About

200 of us, out of the thousand or so men in the camp, said after one

day that we were too weak to walk any further. So they left us, and

the Soviets arrived that night.

FSJ: And then you were repatriated?

RP: Yes, over a long period: it took over six weeks before we got

back into American control down in Odessa.

FSJ: I understand from one of the biographical sketches I read that

you saw a lot of the world on the trip and that was one of the

factors behind your decision to apply to the Foreign Service.

RP: Oh, yes. I’d had no idea many of the things I saw existed. I was

also very concerned that we not have another war like World War II,

and I thought maybe I could help by joining the Foreign Service.

Pretty idealistic of me, but anyway, that’s how I turned up.

FSJ: So then you went back to Kansas State? What was your degree in?

RP: I got a degree in general science. My major was mathematics,

which was a mistake.

FSJ: Why was it a mistake?

RP: I had almost failed integral calculus because the war had

diverted my attention, but I had more hours of mathematics on my

transcript than any other subject. I was not a serious mathematics

student, but I got through it.

FSJ: When did you apply to the Foreign Service?

RP: I took the written exam in Tokyo in 1946, when I was still in

the Army. I took it just to see what it was like, with no

expectation of passing it, and much to my surprise, I passed. So

they let me out of the Army and I went back to school. I got there

in March 1947 and graduated in May; I’d had such a heavy schedule as

an engineering student that there was no problem getting enough

hours to graduate with.

I took the oral Foreign Service exam later that summer in Chicago.

The chairman of the board, a Mr. Eberhard, said to me, in effect,

“We like your style, Mr. Parker, but you don’t know anything. Go

back to college for a year and study about history and economics.”

Which I did.

FSJ: That’s when you earned your master’s degree?

RP: Yes, in something called citizenship education, which was a

“Great Books” program modeled on the one at the University of

Chicago.

FSJ: Tell me about your time with the Kansas State UNESCO

Commission.

RP: Well, it was brief but interesting. Milton Eisenhower, who at

that point was the president of Kansas State, and changed its name

to Kansas State University, was the chairman of the U.S. National

Commission on UNESCO. UNESCO had its first international conference

in Beirut in the summer of 1948, and he wanted to establish a UNESCO

commission in every state. He started with Kansas and got three or

four other states to follow suit, but all of the state commissions

died on the vine not long afterward.

The commission was an early NGO, funded by the university. This was

at the beginning of the implementation of the Fulbright legislation

and the resumption of Junior Year Abroad and that sort of thing.

There had been almost no exchanges before between Kansas schools and

schools abroad, and we were beginning that program. There was a good

deal of interest throughout the state, but the program died after

Milton Eisenhower left to go to Johns Hopkins University.

FSJ: What did your job entail?

RP: I did some local travel, doing things like showing educational

films to groups. One of my favorite films was “No Place to Hide,” an

Encyclopedia Brittanica film about the implications of atomic

warfare. Trying to bring that issue home to farmers in Kansas was

interesting. They were ready to listen.

But the most exciting thing I did was to witness a festival

celebrating the adoption of a town in Holland by a little town named

Morganville, not far from Manhattan, where the university was. That

was a great event. Everyone came from miles around and people

performed on a stage set up in a vacant lot. It was a very rewarding

grass-roots experience.

|

“Beirut was the most fun of my postings. I served there

three times, once as a language student, once as

political officer, and once as

ambassador.”

— Richard Parker |

FSJ: Did anyone from the town in

Holland come?

RP: No. It was a long way to go, and travel was difficult then.

FSJ: You spent about six months with the commission?

RP: Less than that, actually: August to December 1948. So about five

months.

FSJ: And you entered the Service in 1949?

RP: Yes. After I completed my year of graduate school, I came to

Washington and took the oral again in 1948 and passed. I said I was

ready to work, but they said, “Oh, we’ll let you know some day, but

we don’t have any work for you now.” So I went back to Kansas and

took the UNESCO job until they told me to report for training, which

was in January 1949.

FSJ: Where was your first posting?

RP: Sydney. I was the general services officer there, dealing with

diplomatic pouches and customs clearances and things like that. And

I did some consular work, as well.

FSJ: You are perhaps best known as an Arabist. At what stage did you

choose that area for your concentration, and why?

RP: It was while I was in Sydney. I enjoyed consular and

administrative work, but this was a period when we were saying no to

everybody who wanted to come to the United States. I spent the day

saying no to Australians who didn’t understand why they had to be

taken under a quota of 200 immigration visas a year.

That was pretty dreadful and I had a perpetual headache. My

replacement was much impressed when I casually reached into my desk

drawer, pulled out a large bottle of aspirin and popped a couple in

my mouth and chewed them.

Anyway, I decided to become a political officer, which was supposed

to be the road to glory. And I felt I needed to develop some

specialization to get there. This meant studying a hard language.

My wife and I looked at the post reports and the possibilities

around the world. My first choice would have been a specialization

in Japanese or Polish, but neither one of those was open. Coming

home from Odessa during the war, I’d been much impressed with the

sight of Istanbul from the water. Then we stopped in Port Said, so

I’d had a brief exposure to Egypt. Both places looked interesting,

so we narrowed it down to Arabic or Turkish, and I wrote on my April

Fool’s card that I wanted to specialize in one of those, but would

like to have a post in the area first. So they sent us to Jerusalem

in 1951, and I never looked back. It was so fascinating, I spent the

rest of my career working in or on that area.

We started out on the Israeli side of the line and then we moved to

the Arab side. I hired a tutor and paid for Arabic lessons for about

a year before the department invited me to come and join an Arabic

class in 1953.

FSJ: In retrospect, it seems there has always been some stigma

within the Foreign Service associated with becoming an Arabist. Did

you feel that way at the time, and did anyone ever try to discourage

you from making that choice?

RP: Well, the term “Arabist” was no compliment even then, and I

understood that. But it was a fascinating world and language. And no

one ever tried to warn me off from going into it.

FSJ: Which of your postings stand out in your memory?

RP: Beirut was the most fun. I

served there three times, once as a language student, once as

political officer, and once as ambassador. The Lebanese are very

hospitable, and you get to know a lot of people.

Even the last tour as ambassador in the late 1970s, which was a time

of great danger — my predecessor had been assassinated — was much

better than today in terms of security for our personnel. We were

much freer to move around. Even so, it’s no fun to have to go

everywhere in an armored vehicle and not be able to stop and go into

a shop or look at the sights with-out a bunch of bodyguards jumping

out and standing around you, intimidating everybody.

The third time I went to Beirut, I should note, I was plucked out of

Algiers and sent there on very short notice. Algiers was a tough

post, although the security situation was nothing like what it is

today. Back then (1974-1977) I was the only U.S. ambassador

accredited to an Arab country who didn’t have a bodyguard. But I was

the first ambassador to serve there after the resumption of

diplomatic relations, which had been broken in 1967 and restored in

late 1974.

So there was a lot of work to be done. I liked the Algerians, but

the infrastructure there for diplomats and the possibilities were

very restricted. Housing was a great problem, and my staff was

generally unhappy with the fact that Algerians never returned

telephone calls. It was a frustrating place to work in, but

relations have improved a good deal since then.

Still, Beirut was a much easier place to work. I knew everybody, or

had access to everybody, and people were willing to help. The only

problem was, there was no functioning government; it was basically

anarchy. Courts did not operate; judges were

afraid to sentence people for fear of reprisals. The president’s

power did not extend much beyond the presidential palace. But the

Lebanese are very entrepreneurial and found ways to make things

work.

FSJ: Who were some of the people you especially admired or were

inspired by during your Foreign Service career?

RP: I liked all my chiefs but one, who shall be nameless. My first

boss, the consul general in Sydney, was Orsen Nielsen, long since

gone to his reward. His first post had been St. Petersburg, in 1917.

It was 1949 when I met him, so that had been 32 years earlier: it

was so unbelievably remote to me. It wasn’t until I went back to

Amman, I think in 1989 — 33 years after I’d left that post — that I

realized how short a span that actually was.

Nielsen was old-line Foreign Service, very proper. His secretary

said he had a way of pointing out to you that you were inferior. But

still, he was a decent fellow, and an honest man.

My first ambassador was Lester Mallory, in Amman, in 1955-1956. A

former agricultural attache, he was a rough-hewn fellow, but I liked

him very much. He taught me a good deal.

Next was Ambassador Armin Meyer, who’s still around. He started out

as a radio operator, along with Bill Porter, and was still a ham

operator when we arrived in Beirut in 1961. He was our ambassador

and I was political officer. He taught me many things.

Then there was Lucius Battle, who was ambassador in Cairo in 1965. I

learned a lot

from him, too.

I first worked with Stuart Rockwell in the Near Eastern Affairs

Bureau back in Washington from 1957 to 1958, and later was his DCM

in Rabat. He is the most competent Foreign Service officer I ever

knew, but the problem was that he did not leave much for me to do.

I could go on and on …

FSJ: You spent most of your career overseas, but you were in

Washington for eight or nine years. Which Secretary of State do you

most admire and why?

RP: I would say John Foster Dulles. Not because of his personality —

he was very much a cold fish, and he treated the Foreign Service

like a public convenience — but because of his command and control

of the department. He was running American foreign policy. President

Eisenhower was the ultimate authority, of course, but Dulles had no

real competition from anybody else in the structure. Everyone

deferred to him. He was very competent and a good director; he

understood international politics and American interests. I

disagreed with many things he did, but I think only Henry Kissinger

rivaled his control of foreign policy.

FSJ: How would you assess Secretary Powell?

RP: I think very highly of him. He is the first Secretary we’ve had

in a long time who understands the qualities and principles of

leadership.

FSJ: Going back to your career — you were ambassador to three coun-

tries during the 1970s: Algeria, Lebanon and Morocco. What were some

of the challenges you faced as chief of mission, and how did you

handle them?

RP: In the case of Algiers, we had significant American investment

in the petroleum sector: prospecting for oil, building natural gas

liquefaction plants, and so forth. That presence had stayed intact

even during the break in diplomatic relations.

American firms had good working relations, in general, with the

higher echelons of the Algerian government. But they had a lot of

problems with the lower echelons: for example, the Ministry of the

Interior requirement that their personnel obtain an exit permit to

leave the country. Holding their hand and helping them with such

problems was a preoccupation.

Trying to get something done in terms of cooperation in the cultural

field was another challenge in Algiers. Having had open-heart

surgery that left me needing a monthly lab test in a place where the

hospital was sort of anarchical, I was very interested in getting

some kind of exchange going with American doctors to try to improve

local health care. Doing that was a constant preoccupation, and I

had not succeeded by the time I left. In fact, I don’t think it’s

ever come to pass.

FSJ: Was the problem getting institutions interested back in the

States or there in the country?

RP: It was both dimensions, and there were a lot of complications.

For one thing, we didn’t have a bilateral agreement in place on

cultural and educational exchanges, and you had to get that done

first. And once we located an American consortium that was

interested in doing this, some-where up in the north-central states,

getting the Algerian side to cooperate was a problem. I think there

was one brief exchange, and then the thing folded. Initiatives like

that require constant attention from both sides, and if they don’t

get it, they stop.

Also, in contrast to Libya and Egypt and other states in the region

— even during the break in relations, there were hundreds of

Egyptian students in the U.S. — there had been almost no Algerian

students here; just a handful. Algerians didn’t travel to the

States. But that began to change almost immediately after

restoration of relations. We were very surprised to have a long line

of visa applicants, one of whom was a man named Elias Zerhouni, who

is now director of the U.S. National Institutes of Health.

One of my problems was that USIA wanted to close its office there,

which it had operated at a modest level throughout the break in

relations, because of the lack of response from the Algerians. So I

said, send an Arabist to run it and let’s see what hap-pens. They

brought in Chris Ross, and immediately things started moving on the

informational and cultural side.

FSJ: How was your return to Morocco as ambassador? I assume

conditions there were not as difficult as in your other two

ambassador-ships.

RP: Oh yes. I liked the country and the people, and the U.S. and

Morocco have had good relations for some 200 years. But even so, I

didn’t want to go back there because of the way the king treated

foreign ambassadors. He wanted them to be lackeys who played golf

and went to parties and basically waited for him to tell them what

to do. In addition, there had been two coup attempts when I was

there before, and the king was never fully persuaded that we weren’t

involved in them somehow. So I only lasted about six months.

FSJ: Were you “PNG-ed” from there?

RP: No, he said he would not declare me persona non grata, but

declared that relations would not improve as long as I was there. He

was upset because I was unable to relieve him of the [exiled

Iranian] Shah [Pahlavi]’s presence, but his principal complaint

about me seemed to be that I knew too many people.

FSJ: Always a dangerous quality in a diplomat.

RP: Yes, indeed. I was also PNG-ed, in effect, while serving in

Egypt in 1967. President Nasser himself ordered my departure because

he apparently thought I was the real CIA station chief and was

personally responsible for all the bad things he thought the

Americans had done to Egypt. The Egyptians later explained that they

thought I had not acted like a diplomat. I’m not sure what that

meant, but have taken it as an unintended compliment.

Being PNG-ed twice is not a service record, however. I don’t know

for sure, but the man who holds the record may have been James

Leander Cathcart, who was one of the American prisoners in Algiers

in 1785 and rose to prominence in the hierarchy there. He was U.S.

consul in Tunis at the time of the Tripolitanian War that began in

1801. And he was PNG-ed three times: in Tunisia, Algeria and Libya.

This is obviously a subject that needs more research.

By the way, he also lived for a time in Georgetown, on P Street.

FSJ: It’s just a coincidence that you also live on that street, I

take it? It’s not an homage?

RP: Oh, no. I had no idea of that when we bought this house.

FSJ: We’ve already touched on your time in Lebanon, but how much did

the deteriorating security situation affect your ability to do your

job as ambassador?

RP: We certainly had plenty of problems — constant fighting among

the Lebanese militias, Israeli incursions and PLO infiltration along

the southern border, and the invasion of 1978, plus an almost total

absence of judicial activity. But that didn’t really inhibit our

work very much; we had contact with everybody, and the common danger

generated a certain camaraderie among us all. But we did try to do

something about the security situation, not for ourselves but for

the country as a whole. One of the problems was that because of the

State of Siege Law (which came about because of the movie starring

Yves Montand that portrayed the U.S. as teaching the Uruguayan

police how to torture and provoked Congress to pass a law limiting

aid to foreign police forces), we couldn’t give a single bullet to

the gendarmerie, the rural police force, which was an essential part

of the security structure in Lebanon. It didn’t look very impressive

to the outsider, but it was very influential in the countryside.

One of my first assigned tasks after getting there was to try and

arrange a ceasefire between the Chamounists and the PLO in southern

Lebanon, where a firefight was going on. I succeeded, and received a

telegram from Roy Atherton, the NEA assistant secretary,

congratulating me on this. But by the time it arrived, they were

fighting again!

That was the way it went, though. You’d work and work to hammer out

a ceasefire or an agreement and get everyone on board, and then

some-body would fire a shot and it was all over again.

I have a framed cartoon showing a group of Lebanese politicians

standing around in a state of embarrassment, while a hand is

sticking out from behind a curtain — holding a Parker pen that was

labeled “The Godfather.” I’d persuaded this group of traditional

political leaders — Sunni, Shia and Maronite — to agree on an

informal compact by urging that if they agreed to stop fighting each

other, the Israelis and Syrians would not be able to exploit them

the way they had. And they agreed and signed, but five days later,

the fighting started back up.

Some of this is discussed in my book on diplomatic miscalculations,

The Politics of Miscalculation in the Middle East (Indiana

University Press, 1993) and in an article I did for the Middle East

Journal’s Autumn 1996 issue.

The most frustrating thing was trying to get the Lebanese Army to

move into southern Lebanon to take over security. We thought we had

it arranged, but then it was blocked by the Israelis and their local

puppet, who really didn’t want them down there.

FSJ: Speaking of Israel: did you ever have occasion to meet Ariel

Sharon?

RP: No; I did see him twice, once speaking at the Council on Foreign

Relations and once in the Kremlin, in 1990, when we both happened to

be visiting Moscow. But we’ve never spoken.

|

“In

the old days, when an assistant secretary came out to

your post, that was really something. Today, someone at

that level visits every three months or so, and they

sneak in and out.”

— Richard Parker |

FSJ: Do you think Ariel Sharon

will ever make peace on terms accept-able to the Palestinians?

RP: No. Any peace will come in spite of Sharon, not because of him.

FSJ: Were you frustrated by the ban at that time on American

diplomats dealing directly with the Palestinian Liberation

Organization?

RP: Not really; the ban was on formal contacts only. Our CIA folks

in Beirut — Robert Ames, in particular, who was later killed when

the embassy was bombed in 1983 — dealt with the PLO all the time. At

times we saw them as a positive influence in the civil war; they

were more responsible than some of the Lebanese factions. But there

wasn’t much they could do, so there wasn’t much substance to our

dealings with them.

FSJ: Did you disagree with the Bush administration’s initial

reluctance to become engaged in the Middle East peace process?

RP: Yes, I did.

FSJ: And do you think the administration’s “road map” is still

viable?

RP: Well, the ink is still on the paper, so I suppose it could be

revived. But it looks pretty dormant now.

FSJ: Are you a pessimist about a peaceful resolution of the

Israeli-Palestinian conflict?

RP: You know, Adlai Stevenson said that “Optimism is to a diplomat

what courage is to a soldier.” Pessimists don’t make good diplomats.

I am professionally optimistic that there is going to be a solution,

but I must say that when I look at the details, I don’t see how it

will come about.

FSJ: Do you think the U.S.-Middle East Partnership Initiative has

promise?

RP: No, I don’t. I may be wrong, but the whole idea, it seems to me,

is that we’re preaching to the natives, as though the problem is

reform. That isn’t the problem: it’s people and land. Where do we

draw the borders and what do we do about the refugees? There will be

little American-sponsored progress on democracy until we do

something effective about Arab-Israeli peace. The initiative doesn’t

deal with that; we’ve just sort of put that aside, but it’s the

900-pound gorilla in the room. Now, I’m out of touch: I haven’t been

out there since 1997. And I haven’t talked to any Palestinians on

the ground, so I may not know what I’m talking about, but I doubt

it.

FSJ: Do you see signs that Arab societies themselves are starting to

recognize the urgency of reform and are willing to pursue that

process?

RP: Yes, I see some modest signs, even in Saudi Arabia. And that’s

the only way reform will happen — from within. The idea that we’re

somehow going to teach them the way is nonsense. For us to push them

actually makes it less likely to come to fruition.

FSJ: In your view, has our intervention in Iraq been successful?

RP: I felt at the time that it was a tragic mistake to go in there,

that we were going to have a great deal of difficulty in the

aftermath, and that it would engender a good deal of hostility

toward us in the region. I think all those assumptions have been

vindicated.

I also think that if we are safer today than we were on Sept. 11,

2001, it’s because of the security measures we’ve taken, not because

we went into Iraq. That action has actually made us less safe.

FSJ: If there should be a stable, democratic government in Iraq, do

you think it will help pave the way for democratization in the

region?

RP: Oh, yes. Anytime you have a successful change, and the result is

beneficial, that’s going to have an effect on others. And I hope

that is the result in Iraq, but I don’t think we can count on it. We

are a long way from a stable Iraq today.

FSJ: How serious do you think Libya is about moving closer to the

West?

RP: They’ve been talking in those terms for some time. Martin Indyk

(formerly NEA assistant secretary) published an interesting

commentary on this in the March 9 Financial Times, pointing out that

the Libyans were talking about breaking out of their isolation back

in 1999. And I think that desire is the real cause of the change.

Iraq may have increased somewhat their fears of American “cowboyism,”

but they were already moving in that direction on their own.

FSJ: So this is an evolutionary change, then?

RP: Yes. Qaddafi is so unpredictable that one never knows for sure,

but it looks like he is serious about coming clean and restoring

ties.

FSJ: Have you met him? RP: Not to my knowledge.

FSJ: How successful do you believe we have been in getting out the

message that the war on terrorism is not a war on Arabs or Muslims?

RP: I don’t think we’ve been successful at all. The restrictions

we’ve had to introduce on travel and so forth inevitably create the

appearance of discrimination against Muslims. I don’t think there is

any-thing we can do about that other than be as tactful and careful

as possible in implementing the policies.

FSJ: You’ve had a wide-ranging career with several phases — you’ve

been a soldier, a diplomat, a teacher, an administrator, an editor,

and an author. Have the transitions been difficult, or have you

always seen yourself as pursuing several different interests at the

same time?

RP: Aside from my desire to maintain the world’s peace, what really

motivated me and my wife to go into the Foreign Service was a desire

to live abroad and meet other people and learn about foreign

cultures. I’ve been fascinated by these things ever since we

started. Also, I’ve always been intellectually curious about why

people are doing certain things and what it means. And that has led

me to write, and read, and study. I’ve been too busy to worry unduly

about shifting from one thing to another.

FSJ: When you retired from the Foreign Service in 1980 after 31

years to become the diplomat-in-residence at the University of

Virginia, was that transition particularly difficult?

RP: Yes, going from being an ambassador to a college professor was

the hardest transition I made. After being in a situation where

every day was divided up into 15-minute intervals during which I’d

see visitors, and people were constantly asking me for answers to

their questions, suddenly my telephone was no longer ringing. And

nobody cared what I was doing, not even my fellow professors, as far

as I could tell. That took a real adjustment; I think it took me

five or six years to deprogram myself and stop talking like an NEA

officer. Maybe I still am!

FSJ: How long were you at the University of Virginia?

RP: I was at U. Va. for two years, during which time I also held

down the job of editor of the Middle East Journal. And then I

decided there wasn’t enough going on regarding the Middle East in

Charlottesville to keep me busy, so I moved back to Washington. I

kept working at the Middle East Journal, but not quite full time.

FSJ: And you were the first president of the Association for

Diplomatic Studies and Training, right?

RP: Yes, [former FSI director] Steve Low hired me for that. But I

stayed at the magazine for another year or so before leaving to

devote more time to ADST.

FSJ: And then what?

RP: I’d been thinking for years about the theme of miscalculations

in diplomacy and wanted to write a book on the subject. And I

thought the way to do it was to get a fellow-ship at the Woodrow

Wilson Center at the Smithsonian, which I did. And I’ve been a

casual laborer ever since. For example, during the 1992-93 academic

year, I was the Stephen Scarff Distinguished Visiting Professor at

Lawrence University in Appleton, Wisc. (a fellowship set up by the

parents of a student who had been killed in an accident; I don’t

know where he was killed or how). I taught courses on the Middle

East there, which was fun. Then I came back and for one semester

taught a course at the School of Advanced International Studies

(part of Johns Hopkins University) in tandem with Bill Zartman.

FSJ: Tell us about your new book, Uncle Sam in Barbary: A Diplomatic

History (University Press of Florida), that is about to come out.

You’ve been working on that for what, six years?

RP: Even longer than that: since 1990. It’s really been a retirement

project, but during that period I did three other books before

concentrating on this one.

FSJ: What in particular drew you to writing about America’s early

diplomatic relations with North Africa two centuries ago? Is it the

fact that the topic isn’t well known?

RP: Well, a lot of American historians have written on it,

particularly the war with Tripoli, but not much has been done from

the point of view of an area specialist. Only one of these

historians, to my knowledge, has ever been to the area, and that

briefly; most of them have known almost nothing of the local

language and culture.

So Carl Brown at Princeton suggested that I write the history of

those early relations from the perspective of a practitioner who is

knowledgeable about the area to see if it made any difference in the

interpretation.

FSJ: In your introduction to the book, you write that, to the extent

anyone does know about that episode, they’ve drawn the wrong lessons

from it.

RP: Yes, they do not understand what really happened. They think

that “Millions for defense, not one cent for tribute,” is what it’s

all about. They don’t realize that we paid almost a million dollars

to get our men out of Algiers in 1796 — which would be about $15

million in today’s money — at a time when our total annual federal

revenues were about $6 million or $7 million. And force did not

settle anything there, at least initially; one could argue that it

did later, in 1815, but these initial problems with Algiers were

solved by negotiations.

FSJ: But wasn’t that at least partially because we didn’t really

have any navy to speak of at that stage?

RP: Well, yes, but even if we’d had greater forces to bring to bear,

what difference would it have made? All our prisoners there would

simply have been sacrificed; we would not have been able to rescue

them militarily. In the end, we still would have had to negotiate.

My other preoccupation has been Joel Barlow, an American diplomat

from that period. In fact, I was up in his hometown of Redding,

Conn., last weekend to give a talk on him. I helped raise funds to

erect a monument to him in 1998 in Zarnowic, Poland, where he died.

It’s near Krakow.

FSJ: As someone who has written extensively about U.S. diplomacy and

taught it, in addition to being a practitioner, you’ve obviously

seen a good many changes in it over the course of your career. How

has diplomacy changed over the past 50 years or so? Are you

optimistic about the future of the profession?

RP: In the old days, 50 years ago, when an assistant secretary came

out to your post, that was really some-thing. The trumpets would

blare. Today, someone at that level visits every three months or so,

and they sneak in and out.

Communications have so multi-plied that I sense we no longer have

the control we once did. Dean Acheson talks about this in one of his

books: when he was Secretary of State, there was a woman named Mrs.

Halla who ran the correspondence review branch up in S/S. She looked

at every telegram that went out of the department and corrected the

grammar — “You can’t do this, Mr. Parker.” Those days are long gone,

and I’m sure our writing has gotten a lot sloppier as a result.

E-mail also encourages sloppiness.

The deterioration in the security situation has really affected

diplomats’ ability to do their jobs, as well. In places like Beirut,

personal con-tact is so important. And if you’re sitting up on a

hill and you can’t go out without a guard, even for junior

personnel, I think that’s decreased our ability to influence events.

But diplomacy is still necessary. Sometime back, I heard Newt

Gingrich speaking at Georgetown about how the Foreign Service was

becoming irrelevant. But I don’t think he understands anything about

how diplomacy is conducted, or how important it is to have people on

the ground in these places. Personality is everything.

FSJ: Whenever you talk to bright young people today, college

graduates, do you recommend the Foreign Service to them as a career?

RP: Yes, I have given talks on that quite a bit. And I always tell

them that I can’t think of anything I would rather have done with my

life than be in the Foreign Service. There was never a dull moment.

I was some-times troubled or unhappy with what I had to do, but I

never wished I were doing something else.

FSJ: Thank you very much.

|

|

|

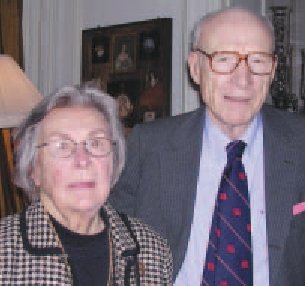

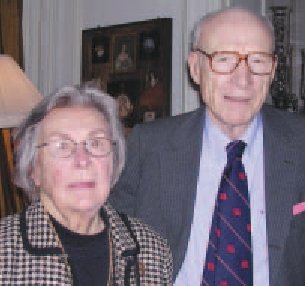

Ambassador Parker and his

wife Jeanne at DACOR on April 14 at the launch of his

new book, Uncle Sam in Barbary: A Diplomatic History.

Ambassador Parker is

married to the former Jeanne Jaccard. They have four

children and nine grand-children. |

|

| The

monument to American diplomat Joel Barlow in Zarnowic,

Poland, erected after a campaign launched by Richard

Parker. |

|

|

Parker (second from left) at the dedication of the

monument in 1998, with Francis Scanlan, Consul General,

Krakow (center), and Polish dignitaries. |

Steven Alan Honley, a Foreign

Service officer from 1985 to 1997, is editor of the Journal.

J U L Y- A U G U S T 2 0 0 4 / F

O R E I G N S E R V I C E J O U R N A L 49 |