|

July 7, 2005 There are already too many personal memoirs

about World War II. So why another? I guess because my

children have asked: “Dad tell us about what you did in

WWII?” So, for what it’s worth, here I go……..

When I was age 17 (June 1942), I started summer school at

UCLA. On November 27, 1942 I enlisted as a Private in the

Army Reserves Corps (ARC Advanced Course CAC, ROTC). (See

Appendix [i]) My Medical Examination showed I was 69” tall

and weighed 146 pounds. (See Appendix [ii]) It had me as

20/20 in both sight and hearing. There was a notation on the

Physical Examination describing my "Flat Feet". The examiner

chose to disclose the condition on the report, which later

on was to come home to haunt me. He could have added,

“Balding Head, Yes.”, but he didn’t.

On May 10th, 1943, I reported to Ft. Mac Arthur, California

(SCU No. 1959, Reception Center) for active duty in the Army

of the United States. Serial Number 19131821. (See Appendix

[iii]) On May 14th, 1943 I reported to Camp Callan,

California (just North of La Jolla) for Coast Artillery

basic training. My Medical Record of that date made me one

year older (incorrect year of birth was shown) and 1 & 1/2

inches taller 70 1/2”).

This report showed: Feet Pes Planus 1st degree. Everything

else on the report was NORMAL. (See Appendix [iv]) At Camp

Callan I was assigned to B-53 AA TNG BN CA. (That’s an

Anti-Aircraft Training Battalion, Coast Artillery) Record

indicates I was admitted to the Station Hospital on June

10th 1943, with a temperature of 101.2. After lots of Sulfa

drugs, I was discharged from the hospital on June 17th. On

June 18th, I was ordered to report to Orthopedic Out Patient

Treatment Clinic for “flat feet, if necessary.” (See

Appendix [v] and [vi])

My “Return to Duty” report now stated: “Nasopharyngitis

acute catarrhal” and “Pes Planus bilateral 2nd degree,

non-symptomatic”. (See Appendix [vii]).

At Camp Callan, privates in basic training were given an

offer to take a competitive exam to attend West Point

(through the West Point Prep School (USMAPS) at Amherst

College in Massachusetts. I took the exam, and on July 1st,

I was notified of my acceptance to attend the school.

Arriving at the USMAPS in August (now a Corporal) I was

given a “final” physical exam. During the physical exam, the

Doctor asked me to jump up and down several times.

While doing so, he looked at my feet. He then asked me to

show him my shoes. I went to get them, but he followed me to

where my clothes were. As I picked up my shoes he took one

from me, reached into it and removed my arch support.

At that point, he knew and I knew, what was to come. The

doctor told me I had “flat feet” and therefore could not

attend West Point.

I was sent to an ASTP center at City College of New York

(CCNY).

The interviewer said he had never before faced the problem

of reassigning a Corporal headed for West Point and asked me

what I thought I would like to do. I suggested sending me to

UCLA, which they did, August 30, 1943.

I entered school at UCLA in September. Although I don’t have

any records of that time, I believe it was in the ASTP. I

was in the Army, and lived on Campus.

Could it have been that I was somehow back in the Coast

Artillery ROTC?.

At the end of the semester at UCLA (March of 1944), our

whole class (about 30 of us) boarded a train in downtown Los

Angeles, and headed East to attend Coast Artillery Officer’s

Candidate School (OCS) at Camp Davis, North Carolina.

After several days, the train arrived in New Orleans, where

we were informed the OCS at Camp Davis was being closed (too

many Coast Artillery Officers --- no more were needed) so we

were being re-routed to OCS at Fort Benning, Georgia (The

Infantry School). As soon as we arrived, we were assigned to

Class 333.

The next 90 days is another story (all to itself). About

one-third of Class 333 graduated OCS on June 20, 1944. I now

had a new set of “dog-tags” and a new serial number:

0551911. After a two-week furlough (See Photograph of me in

Appendix [viii]), I reported to the

106th Division, at Camp Atterbury,

Indiana.

Because I had 90mm gun training, I was assigned to command

the 2nd Platoon, Anti-Tank

Company, 422nd Infantry Regiment.

Quoting from the 106th Division’s web site: “The Division

was activated in Fort Jackson, South Carolina on March 15,

1943.

After completing Tennessee Maneuvers in late March 1944 the

Division was transferred to Camp

Atterbury Indiana, near Columbus just south of

Indianapolis, Indiana. While there the Division lost over

7,000 enlisted men and 600 officers who were sent to

replacement depots. Many of the 106th men were sent to the

Fort Meade, Maryland Replacement Depot and ended up in

divisions that became a part of the invasion of Europe in

June of 1944.

Over the summer of 1944 the Division was filled with

replacements from other training units, the Army Air Corps,

Army Specialized Training Program (ASTP), Coast Artillery

and AAA Artillery units and others.” (End of quote.) On

October 21, 1944 the 422nd and the 424th sailed from New

York aboard the R.M.S Aquitania (See Appendix [ix]). (She

was the sister ship of the "Mauritania", the ship on which

my mother and dad sailed to Europe, in 1927.) This Cunard

Liner had been converted from a passenger ship to a troop

ship on November 21, 1939. With a displacement of 45,647

tons and a speed of 23 knots, she did not need an escort

while sailing across the Atlantic (3600 miles) in less than

seven days. In peacetime the ship accommodated 597 1st

class, 614 2nd class, and 2,052 third class passengers. In

October of 1944, there were over 6,000 of us aboard on our

way to Scotland.

At the end of the first day at sea, I joined my fellow

junior officers in the ship’s dining room. White

tablecloths, “Cunard” china, glassware, and flatware. We

were even provided a glass of wine with the meal. The word

“Posh” comes to mind. After dining, I went below to see how

the men in my platoon were faring.

The outpouring of “gripes” was immediate. “We had the food

slopped into our mess kit, all mixed together, and then with

no place to sit, we had to stand at elevated thin benches,

to eat our meal.” I went to Captain Vitz, my Company

Commander, to ask permission to take my meals with my men.

“Lt. Prell, we are guests of the British navy, and we will

accept their hospitality and not act in any way, which might

embarrass them, Permission denied.”

From the time we left New York, until we arrived in

Greenock, Scotland (October 28th) the Division was one

“Gigantic Poker (Crap) Game”. I wouldn’t doubt that several

of our troops retired on the earnings made during that

crossing.

After disembarking, the 422nd boarded trains in Glasgow and

were taken to the Cotswold area of England. I was billeted

in a Manor House in the village of Fairford. We spent the

next several weeks in training and two days before

Thanksgiving, I was given leave to travel to London to spend

the holiday weekend. Needless to say, war and all, I

immediately feel in love with London! (I know ….. that is a

whole other story.) The Division crossed over to France on

December 6th, landing in Le Harve and then going directly

the small Village of Yerville (population 2,000). Our

bivouac area was nothing more than open fields, deep in mud,

with cold drizzling rain.

That evening as my Platoon Sergeant and I sat talking, he

asked me, “Lieutenant, how old are you?” (I was 20 and he

was 32). I replied, “Not too far from you, Sergeant.” He

said, “I thought you were about my age, some of the men

think you’re a lot younger.” At that time, I was already

balding, which no doubt added a number of years to my age.

After a few days, as we were readying our units for the move

to front, I was ordered to report to Regimental

Headquarters, for a special assignment.

“Lt. Prell, your platoon is to place road guards at a number

of critical points along the route from the town of Givet

(France) to St. Vith (Belgium).” The route we were to take

to get from Yerville to Givet was N29 to the N28 to

Neufchatel. Then the N29 to Amiens.......Cambrai and

Valenciennes. Then the N49 to Maubeuge and into Belgium to

Philippeville. The regiment was to spend the night in the

vicinity of Philippeville, and then move out at daybreak,

headed for St. Vith. However, my platoon was not to stop in

Philippeville, but was to go directly to Givet (which was

back in a sliver of France) where I was to start placing

road guards to be sure the troops went down the correct

roads (and in the right direction). So with map in hand, I

led my platoon on the road to Givet.

The rain had stopped, so the men would be able to set up pup

tents (for the night) at each location along the route to

St. Vith. Instructions were given for the men to be in place

at sunrise, and to direct the column along the correct

route.

They were told to wait to be picked up by us, after the last

of the column passed their checkpoint.

Since the route went straight through Givet, I put out two

men (who linked up with road guards from another unit) and

instructed them to wave the troops straight ahead toward

Wellin.

Then about 32km East of Givet, at the road junction at

Wellin, a sergeant and two privates were instructed to

direct the troops north toward Rochefort. Two more men were

dropped off in Rochefort and three more in Marche, where the

column was to be turned 90-degrees to the right on a road

that went directly to La Roche-en-Ardenne.

In La Roche as we dropped off three more members of my

platoon on the south side of the bridge over the Ourthe

River, I said to my Platoon Sergeant, "This is where we will

return and spend the night after we have dropped off the

last of our road guards in St. Vith". I can't begin to

describe the beauty of La Roche -- picture perfect -- a

travel agent's dream. There were three of us in my

jeep......my driver, Tec 5 Ken Fielen (from Chicago),

Sergeant Roger Phillips (from West Union, West Virginia) and

me. We were making good time and the prospect of spending

the end of the day in La Roche was enticing.

Another two men were dropped off on the north side of the

bridge and another three where the road turned and led out

of town toward Vielsalm. Two more men at the crossroads

about 17km east of La Roche (the road goes straight through,

but could cause trouble) and another two at the T-junction

just south of Vielsalm to direct the troops north to

Vielsalm. Then three more in Vielsalm to handle the

90-degree turn east to St. Vith.

In St. Vith we met up with the advance party and reported

that the road guards were in place. I had one of 1-1/2-ton

trucks return to Givet with a driver and one other man, with

instructions to follow up after the last of the troops had

cleared Givet and to pick up our men at the locations I had

marked on a map. The remaining members of my platoon (with

the other 1-1/2 -ton truck) were to remain in St. Vith until

the next morning, when they were to return to La Roche and

meet me at the bridge over the Ourthe River.

With all the road guards in place, we three happy tourists

headed back to La Roche to find accommodations for the night

-- hopefully to include a real bath and a good meal as well.

In the center of town, overlooking the river, we found a

charming small hotel, where I booked us in for the night. We

had our first hot bath in over a week...a fine meal,

including wine, and real beds, with comforters to keep us

warm.

The next morning, we got up and headed back along the route

to check on how our road guards were doing. Everyone was up

and in place, that is until we got to Marche, where we found

the column was headed northeast toward the village of

Hotton. Sgt. Phillips jumped out and woke up a corporal and

two privates who had overslept, and got them to direct the

following units toward La Roche.

Meanwhile my driver and I raced ahead of the column (only a

few units had actually passed the checkpoint) and turned

them toward La Roche at Hotton.

By the time they arrived in La Roche, it was no problem for

them to meld into the column crossing the bridge; and

although they might have been questioning the fact that they

were meeting other units coming in from the right, the

distances were such that they were still very near the head

of the column. When, the next day, I was called to

Regimental Headquarters, I knew it was to arrange for my

Court's Martial. Instead it was to congratulate me on the

fine job my platoon accomplished! In 1948 I again visited La

Roche-en-Ardenne. The charming village was no more.

Although rebuilding had begun, the place was a mess. I

learned that early in January of 1945, American intelligence

had found a number of German tanks in La Roche, so a flight

of bombers was sent to eliminate them.....which was

accomplished, but in doing so, the center of La Roche was

almost completely destroyed. In 1994, Bette and I attended

services in Bastogne commemorating the 50th anniversary of

the Bulge. Again visiting La Roche, I found much of the

charm had returned, but nowhere near what existed early in

December of 1944.

So, on December 10th, with Lt. Prell leading the way, the

men of the 106th arrived at the front to replace the U.S.

2nd Division on the line. This was the Schnee Eifel area of

the German/Belgium border east of St.Vith, Belgium, and the

2nd Division was replaced man for man and gun for gun by the

106th. The normal coverage, for a Division on the front

line, was approximately five miles. The 106th's positions

extended for 21 miles and jutted out, like a thumb, into

Germany in a salient extending approximately seven miles.

Quoting from the 106th Division’s web site: “At that time,

the average age of the men of the 106th was 22 years. On 16

December, 1944 the Germans launched their ARDENNES

OFFENSIVE.

The 106th positioned in the Schnee Eifel salient was hit

with their full force.

After three days the 422nd and 423rd Regiments were

surrounded and completely cut off from the rest of the U.S.

Army. The 424th Regiment, whose position was south of the

422nd and 423rd, were able to fight and withdraw. They

joined the 112th Regiment of the 28th Division, who was in

position just south of the them. The two regiments, the

424th of the 106th and the 112th of the 28th, formed a

Regimental Combat Team. They were successful during the

oncoming days of January to help repel the German forces

from the former Allied positions. The battle which lasted

from 16 December 1944 to 25 January 1945 was known in the

U.S. Forces journals and history books as The Battle of the

Bulge. European historians refer to the same battle as The

ARDENNES OFFENSIVE.

The 106th Infantry Division, when they caught the brunt of

the German Offensive on 16 December 1944: · Had been on the

Continent only 15 days.

Had been in place in a "quiet" sector for orientation.

· Had the youngest troops (average age - 22) of any American

Division on line.

· Had been in their new positions only five days.

· Had no prior warning that the Germans were going to

attack.

· Occupied a front line that covered over three times the

normal distance.”

When my Regiment (the 422nd) replaced the regiment of the

2nd Division, my Platoon replaced the 2nd Platoon of the

corresponding Regimental Anti-Tank Company. That put my

platoon on the northern most position of any unit in our

division. Looking out from where my 57mm guns were dug in,

the ground fell away, and then rose again to a ridge about

1,500 yards away. Two of my guns pointed forward, the third

was facing about 45 degrees to the left. The gun

emplacements and the log-bunkers where we slept had been

prepared by the men of the 2nd Division, and they were a

work of art. There was a gap, between the 106th and the

closest unit on our north, which was the 14th Cavalry

Regiment.

The 14th was the northern most unit of the VIII Corps.

Between the VIII and the V Corps was an area called the

Losheim Gap, which turned out to be where the German Army

chose to make their strongest attack.

This area is described by Colonel D. J. Judge: “Along the

border between Germany and Belgium, there is only one region

conducive to military movement.

It is 5 mile wide area known as the Losheim Gap, named for

the Belgium town of Losheim. The area contains numerous

valleys and steep hills supported by a limited road network.

During World War I, German horse cavalry advanced westward

through the gap and quickly reached the Meuse River. The

same thing happened in 1940; Field Marshall Erwin Rommel's

division sped through the Losheim Gap to gain the Meuse

River and then push on to the English Channel.”

So again, the German high command chose this area as the

most likely to produce the results that had been achieved in

the past. It seemed as if the allies had not read their

history books. I certainly hadn’t, and here I was, at the

pivotal point, in both geography and in time.

What happened during the next few days? From the records of

the division: Killed in Action: 417, Wounded in Action:

1,278, Died of Wounds: 53, POWs: 6,697(of which 6,500

eventually returned to military control after being captured

in the ARDENNES OFFINSIVE).

There have been many accounts written about those few days.

I doubt if any single one of them can adequately describe

the events in a way that might carry the horrific impact we

of the 106th Division experienced. I choose the following,

because it was written by someone who, when the battle

began, was only a short distance from me. When you read this

account and you see references to the 422nd Inf, the Schnee

Eifel, and Schoenberg, he is talking about me.

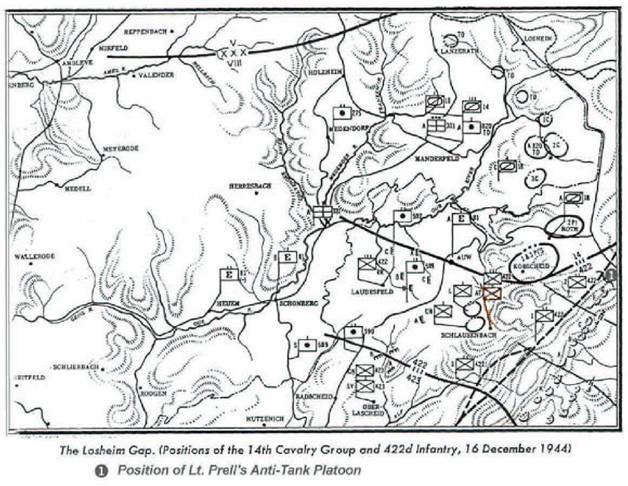

MAP 1

A World War II experience as told by Colonel William M.

Slayden II: THE BATTLE OF THE BULGE The Battle of the Bulge

or Hitler's Ardennes Offensive (WACHT AM RHEIN) as the

Germans called it started on Dec. 16, 1944. At that time the

British and the Ninth U.S. Army were participating in the

Allied offensive, which was then taking place along the Roer

River in Holland and northern Belgium. My unit, the VIII

Corps of the U.S. First Army was holding a quiet sector

along the German Belgium border south to the Duchy of

Luxembourg in the center of the Twelfth Army Group.

On this the first day of the big German offensive I was in

St. Vith, Belgium. I was ordered there on special duty three

days earlier to assist the 106th Infantry Division,

particularly the G-2 Intelligence Officer, in getting

oriented to combat operations. The 106th Inf. Div had just

arrived from the States, and every man in the division,

though fresh from training in the States, had no prior

battle experience. They were to take over a quiet sector of

the battlefront, man for man and foxhole for foxhole, from

the 2nd Infantry Division, which was ordered north to the

Roer River front. The 106th had taken over their sector in

good order, and for the past three days all was quiet on

their front along the Our River and Schnee Eifel. On Dec.

15, 1944, the day before the great battle started, I made

the following entry in my diary: "General division

activities all day. Our mission is purely defensive so there

is no activity except patrolling on the front. The Div

captured its first two Prisoners of War (POWs) today. They

were deserters and were sent back to the rear for

interrogation. Will return to Corps HQ in Bastogne tomorrow

if nothing happens to interfere".

Little did I, or any other officer or soldier in the U. S.

Army, know what a tremendous armored force the Germans had

massed along this quiet sector of the front in complete

secrecy. They were poised and ready for the attack to begin

the next morning. Only after the war ended did we discover

that a force of some 5 panzer divisions and 12 grenadier

divisions with over 500 tanks and 1900 other guns (werfers)

were moved in complete secrecy into this "quiet" front

extending from Losheim on the border of Germany and Belgium

on the north, then south along the Schnee Eifel and Our

River to Ecternach in Luxembourg.

The U.S. had only one Corps (the VIIIth) with three

divisions along this line - 106 Inf. Div with

the 14th Cavalry Recon Regt attached, the 28 Inf. Div and

Combat Command.

The VIII Corps on Dec. 16, with Headquarters at Bastogne,

Belgium, was resting up and refitting after the surrender

and capture of Brest, and the long march across France. The

Corps had only a defensive mission of holding the "quiet

front" while the main Allied fighting was occurring to the

north.

We had been there for about two weeks when I was ordered to

St. Vith, some 45 miles northeast of Bastogne, which was the

HQ of the newly arrived 106th Infantry Division As a

supposed combat experienced staff officer, I was given the

special duty to advise and consult with the 106th Division

in its initial entry into the line of battle. The Div was to

take over man for man the positions held by the Div it was

replacing. The 14th Cavalry Regt, attached to the 106th, was

on the left (north flank of VIII Corps), and held the sector

of the Losheim Gap between the 99th Inf. Div and the 106th.

Then came the 422nd, 423rd and 424th Inf. Regts. in that

order on the Schnee Eifel, a snow covered ridge along the

German border.

These three regiments occupied the same locations as their

predecessors, which were German bunkers in the old Siegfried

Line. Some of the supply roads along this high ground were

subject to observation by the enemy and were fired on

occasionally. I had visited these positions when occupied by

the 2nd Div and realized the exposed position they were in.

South of the 106 Div was the 28th Inf. Div with the 110th,

111th, and 112th Regts, and then CCA of the 9th Armd Div

along the west side of the Our River.

Some 60 - 70 miles of front thinly held.

The Battle of the Bulge started on the early morning of

Saturday December 16th, 1944. On that day my Diary has this

entry: "The Germans started shelling St. Vith at about 0400

this morning, and attacked all along our front at daylight.

During the morning it appeared that the action was only a

reconnaissance in force, but about noon we captured a series

of orders from Rundstedt, through Modell to the 62nd

Volksgrenadier Division, a new division on our front,

indicating that the attack was a general offensive all along

our line. The 116th Panzer Division was identified on the

106's right flank by the U.S. 28th Inf. Div. By 1430 hours

the 14th Cav Group on our left was in general retreat. I

went out to Andler (a strong point on the front manned by

the 14th Cav Group in the Losheim Gap) to check the

situation. It was discovered that the units of the 14th Cav

were badly disorganized and in confused retreat as result of

considerable pressure being put on them by the German 18th

Grenadier Div reinforced with tanks. Andler fell later in

the afternoon and Schoenberg is threatened. (Schoenberg is a

key road junction on the supply route for the 422nd and

423rd Regts and the approach to St. Vith).

Gen Jones (commanding the 106th Inf. Div) debated whether to

withdraw the 422nd and 423rd Regts from their positions in

the Siegfried Line (on the Schnee Eifel) as their only line

of retreat or withdrawal was through Schoenberg. VIII Corps

promised that the 7th U.S. Armored Div would be here in the

morning for reinforcement so he (Gen Jones) decided to hold.

VIII Corps also promised CCB of 9th Armored Div. "That was

the entry in my diary, but I recall much more detail of the

day's events.

During my visit to Andler it was discovered that our front

along the Losheim Gap was falling apart. The strong points

protecting the Gap had lost contact with each other and were

in retreat. Death and destruction of equipment from the

surprise attack by enemy tanks was evident everywhere and

was still going on.

I was almost captured myself. The area east of Schoenberg

was "crawling with Krauts" as we called them. The left flank

of the 106th Div and the Corps was now exposed to attack by

enemy forces, and we were out of contact with U.S. First

Army units on the north. But the center of the division, the

two regiments on the Eifel and occupying the German

Siegfried Line bunkers, had held firm and even repulsed one

or two attacks.

Upon return to St. Vith after discovery of the breakthrough

at Andler, reports from the 14th Cavalry confirmed that the

Group was in full retreat and had abandoned its headquarters

in the village of Manderfeld. The Colonel commanding the

14th Cav, (I won't mention his name because he was later

relieved and court-martialed because of his unauthorized

retreat), came to me seeking information of enemy forces and

locations of elements of his own scattered forces. He

described the bitter fighting in the border villages, Roth,

Kobsheid, Auw, etc., the sudden appearance without warning

of enemy tanks and infantry in a smashing attack early in

the morning, and their confusion and retreat with what few

vehicles they could get going on the icy and snow covered

roads. Many troops were captured or left behind as the

command structure was cut off, communication lost and men

and equipment scattered in the cold and snow covered forest.

This utter confusion in the front ranks was participated in

by me during my Andler trip, and it was real. Casualties

were heavy, both in personnel and equipment, due to the

suddenness and overwhelming force of the attack. The Colonel

commanding, not having had any experience in combat and

enjoying the "quiet front" positions for several days which

he took over from his predecessor, to be suddenly awakened

by an artillery barrage and then a tremendous tank and

infantry attack on his entire front was at least unnerving,

and the cause of what I concluded to be his "shell shocked"

condition.

When the Col. made his report to Gen. Jones he was

immediately sent to the rear, and Gen Jones called a meeting

of his staff to decide what to do as a result of the

collapse of his left flank.

From the information gained from the enemy that first day,

however, and the captured documents from Genfeldmarshal Gerd

Von Runstedt to Genfeldmarshal Walter Modell and the 62nd VG

Div on our front, it was obvious that this was no

reconnaissance in force but a general offensive all along

the American line. The captured order was immediately sent

back to VIII Corps and then on to SHAEF Headquarters. Gen.

Eisenhower was as surprised as the front line soldier of the

106th, as it took him a while to accept the factualness of

the Runstedt order, and have his staff confirm the order.

But that's the way it was, and now the whole world knew that

the Battle of the Bulge was on.

The collapse of the 14th Cav. on the left flank of the 106th

Division left Gen. Jones in a precarious position. The

division must have immediate reinforcement to protect the

strong defensive positions of the regiments on the Eifel and

to restore the situation on the left.

Gen. Jones had called a meeting of his staff, or a "council

of war" to decide what to do about the collapse of the 14th

Cavalry and the Schoenberg situation. With the information I

had gained on my visit to the front, I was called upon to

give a detailed briefing on the enemy situation and

capabilities. The breakthrough of the 14th Cav positions in

the Losheim Gap exposed the left flank of the division to a

penetration from the northeast along the road from

Manderfeld to Schoenberg, and the area to the north of St.

Vith was uncertain, as we had no contact with front line

units of the First Army to the north of us. The fall of the

villages of Roth and Auw along the "Skyline Drive" behind

the 422nd and 423rd Regts occupying the bunkers on the

Schnee Eifel would allow the Germans to penetrate from the

east to Schoenberg. Since Schoenberg was behind (to the west

of) the two Regts it was a key road junction for their

withdrawal. The terrain and road network was such that they

could not be withdrawn except through Schoenberg.

Although we did not know the identities of the attacking

enemy units at that time we did know from Modell's order

that the Germans had massive tank forces and could capture

Schoenberg as we had no defending force there.

The decision to hold the defensive positions on the Eifel or

withdraw in face of the threat to Schoenberg was up to Gen.

Jones. The day's standing order to all units had been to

hold their positions. Reinforcements had already been

requested and Corps Hqs was aware of the situation.

Before making his decision, Gen. Jones decided to call his

boss, Maj. Gen. Troy Middleton, VIII Corps Commander, who,

incidentally, was my boss also, and who had ordered me to

St. Vith in the first place. In their phone conversation,

which I was privy to, Gen. Middleton said that the 7th

Armored Div. would be there (at St. Vith) by 0700 hours, and

for Gen. Jones to hold his positions if possible.

After some further discussion Gen. Jones then turned to me

and his G-3, a Lt. Col. Brock, and asked what we

recommended. Now, the boy from Waverly and Humphreys County,

Tennessee was on the spot. I was there because I had had

more experience in combat than the others, and certainly had

more knowledge of the present disastrous situation, both

friendly and enemy, because of my earlier reconnaissance

around Andler and Manderfeld. He wanted my opinion, and

there I was about to help in making a history making

decision, but I didn't know it at the time.

I was positive in my advice to Gen. Jones that if Schoenberg

was overrun in tomorrow's fighting the two regiments would

be cut off. The supply roads for the two regiments passed

through Schoenberg and then west to St. Vith. If Schoenberg

fell, and it most certainly would as there was no force

there to defend it, the enemy would be behind the two

regiments on the Eifel and they would have to fight their

way out.

With regard to the 7th Armored Div being in St. Vith by 0700

hours tomorrow, I was really on the spot. The 7th Armd Div

had recently been withdrawn from the Ninth Army and was

somewhere to the north en-route to VIII Corps, perhaps

around Vielsalm and Salmchateau some ten or twelve miles

northwest of St. Vith which was some six or seven miles west

of Schoenberg. And it was well known to any soldier with

combat experience the difficulty of movement of military

equipment at night with no lights in the Ardennes. The

treacherous condition of the muddy, ice and snow covered

roads in the area, and above all the confusion which now

existed in the heat of battle among retreating and

withdrawing forces, those trying to hold their positions,

and remnants of those wiped out by the attack, made movement

almost impossible. I told Gen. Jones that I doubted if the

7th Armd Div with its tanks and heavy equipment could move

through this area under the present blackout conditions, in

the dark of night and confused road situation existing as a

result of the breakthrough to the north, to arrive at St.

Vith by 0700 hours.

But Gen. Jones, in view of Gen. Middleton's promise of

reinforcement by 0700 hours and order to "hold his positions

if possible", decided to hold.

In retrospect I should have insisted that Gen. Jones at

least start the movement of the 422nd and 423rd Regts back

from the Eifel right now while we still were in

communication with them, and be prepared to defend

Schoenberg as a route of retreat if necessary. I was sure

that the 7th Armd Div would not be in St. Vith by 0700 hours

much less be able to stop the two pronged attack on

Schoenberg from the northeast and east. Schoenberg had no

defending forces, was the junction of roads coming from the

northeast, east and south, then crossing the Our River and

on west to St. Vith. But I would have had to disbelieve my

own Commanding General and disregard his orders. That is one

of the things you just don't do when at war.

Little did I know then that Gen. Jones' fateful decision to

hold those positions would result in the loss of the two

regiments.

The next day, Sunday December the 17th, the second day of

the battle, dawned cold and cloudy with snow flurries

occasionally. The weather was so bad that the Allied Air

Forces were ineffective. The following entry was made in my

Diary: "Sunday Dec. 17, 1944.

"The 7th Armored did not show up this morning and word was

received that it would be noon before the first elements

arrived. The Germans exerted pressure from the south

(village of Bleialf) and took Schoenberg, thus surrounding

and cutting off the 422nd and 423rd Regts. Since we had no

communication with the regiments, I went out to check the

situation at 0930 hours and discovered everyone in retreat

west of Schoenberg. There were no infantry forces between

Schoenberg and St. Vith. I communicated with Gen. Jones and

gave him the situation. He said delay them as much as

possible as Lt. Col. Riggs with the 81st and 168th Engineer

Battalions was coming out to block the road to St. Vith. I

took charge of an armored car with a 50-caliber machine gun

and several jeeps with 30 caliber machine guns, and with

this little force delayed the advancing tanks and infantry

for the next 4 - 5 miles until Riggs came into position

about 1530 or 1600 hours. We were face to face with the

enemy as they came around bends in the road, placed as much

fire on them as we could, and then retreated to the next

bend. This would cause them to stop and reconnoiter before

proceeding. On one occasion a German infantryman in a

snowsuit stepped around a corner in the road just as I was

easing around it myself.

He was as surprised as I and jumped back.” "When we finally

stopped them about I mile east of St. Vith on the other side

of a hill they had 4 tanks at a bend in the road in plain

view of my OP.

But we had no tank destroyers or tanks until it was dark and

too late to take a shot. Our meager air support, because of

the weather, strafed them after we gave the exact location

and description, which disrupted them to some extent. Our

Air reported 60 vehicles in the column, 10 of which were

tanks.” "After dark and the action subsided, I returned to

HQ, made my report, and got some much needed food and

sleep." The details of this second day of the Battle of the

Bulge are very vivid in my memory. It was the day I came

face to face with the enemy and acted like any other soldier

would act under the circumstances to keep from being killed

or captured.

When it was realized that the 7th Armored Div could not get

to St. Vith that morning and reinforce the 106th, and our

communications with the two regiments on the Eifel were

cutoff, disaster was about to happen. Gen. Jones had no idea

what the situation was on the Schoenberg front, nor did any

one else at HQ.

Contact had been lost with the two regiments. They had

strong positions and could defend themselves for a couple of

days, but the troops had to have supplies and reinforcements

to hold out for any length of time.

It was my job to keep the division advised of the enemy

situation, and that was when I decided to go to Schoenberg

myself and find out. I got in my Jeep with the driver at the

wheel and we headed out toward Schoenberg. The road was

frozen, snow was on the ground, but it was fairly clear. No

troops were on the road as we left St. Vith, but soon I

noticed some scattered stragglers and vehicles in retreat.

It was obvious the enemy was only a few miles ahead. As we

came to a sharp turn to the left the driver slowed down,

stopped, and said, "Col, its awfully quiet around here and

this looks suspicious. Maybe you better take a look around

this curve before we go barging on." I got out and hugging

the bank on the left side of the road I was easing myself

around the curve when suddenly I saw a German soldier clad

in a white cape or snow suit hugging the same bank and

easing himself around the curve in my direction. We

recognized each other immediately, and were so startled that

we both turned and ran like hell. He was armed with a rifle

but didn't use it. I was armed with a pistol but didn't try

to shoot until after I shouted at my driver to turn the Jeep

around and let’s get out of here.

As we raced for cover, all hell seemed to break loose. The

Germans now figured they had run into the enemy retreating

from Schoenberg and laid down a heavy fire. Every fifth

bullet in machine gun fire was a tracer and you could see

where it was coming from and where it was going to. Soon we

ran into some of our retreating forces and together we

returned their fire as best we could.

Now I knew what the situation was. Schoenberg was captured

and this was the point man of a German panzer force moving

toward St. Vith. There was nothing to stop them. The 422nd

and 423rd Regts were now surrounded and cut off Gen Jones

must be advised. The Division Headquarters was exposed and

subject to attack.

Among the forces we ran into as we moved back toward St.

Vith seeking cover from that encounter at the curve, were

some Signal Corps troops felling trees and retrieving

telephone wire along side the road. We joined up with these

forces and placed as much fire on the enemy as we could,

knowing all the time that he was coming around our flanks -

we could see an occasional white robed German soldier jump

from cover to cover - and that we could not hold out for

long.

Unbeknownst to me at the time of my encounter with the

German soldier on the Schoenberg road, however, was that the

division signal officer had been in Schoenberg early that

morning as the German tank attack came down the Andler Road,

and had pulled back to west of Heuem when Schoenberg fell.

In the book- ST VITH, Lion in the Way, by Col. R. Ernest

Dupuy, published by The Infantry Journal Press, which

reports all the action of the 106th Inf. Div in the Battle

of The Bulge, there is a short article at page 66-67 which

makes mention of this action on the Schoenberg Road, and is

quoted as follows: "TWO LIEUTENANT COLONELS ON THE ST. VITH

ROAD" "Up at Division forward switching central at

Schoenberg early that morning was Lt. Col. Earle Williams,

Division Signal Officer; with him was Master Sgt. Clyde F.

Foster, wire chief. Enemy fire was falling in the village;

the switchboard was frantically trying to clear traffic.

Down the valley of the Our River from Andler came the German

tanks.

"Williams ordered the board destroyed and its crew to clear

out, then took off on the road with Sgt. Foster --- to

Heuem. West of Heuem, --- (they) started felling trees for a

road block.

"In the meantime another lieutenant colonel was

reconnoitering along the Schoenberg Road. This was Slayden,

Asst Corps G-2, mentioned previously, who at 10:00 AM

started for the front to see for himself how matters were

going.

"Slayden worked his way up through the west bound traffic,

past the driven-in cavalrymen to near Heuem, began to

receive hostile fire and turned back. At 11:45 he tapped the

line, 1500 yards west of Heuem and told G-3: 'I'm the last

man between St. Vith and Schoenberg. German infantry has

reached the point where the road from Schoenberg turns north

from the Our River. Artillery has one scout car and five

jeeps here.

Could delay the enemy if we could get artillery fire.

"Division told Slayden the 81st Engrs. were coming up the

road to prepare close in defense, and asked him to establish

any delaying tactics he could.” That was a pretty tall order

for a staff officer who was used to telling others how to

fight the enemy instead of doing it himself. But the whole

command was in immediate danger if this enemy advance was

not opposed.

**************************** Let me now interrupt Col.

Slayden’s story and come back to my own recollection of what

happened the middle of December, 1944.

Note: To read the balance of Slayden’s report log onto:

http://www.grunts.net/wars/20thcentury/wwii/slayden/slayden1.html

The 106th had moved into position on December the 11th.

Here I was in a log bunker, warm and quite comfortable. The

Lieutenant (of the 2nd Div. I had replaced), told me that we

were the farthest, northernmost unit of the Division. He

said: “there is a “Recon” outfit just over there (pointing),

but I haven’t met any of them, they seem to stay put.” His

men had built the log bunkers and gun emplacements, and he

hoped I would enjoy them. Two of my guns pointed forward,

the third was facing about 45 degrees to the left.

From our Company Headquarters back in Schlausenbach (see Map

1), hot meals were sent forwarded every day. It was cold,

but it hadn’t been snowing since we arrived. After all, we

were relatively safe; this was to be a quiet part of the

front. That is why they spread us out (side-by-side, and not

the usual two regiments forward and one in reserve) across a

front of over 21 miles. As was stated before “the normal

coverage, for a Division on the front line, was

approximately five miles. The 106th's positions extended for

21 miles and jutted out, like a thumb, into Germany in a

salient extending approximately seven miles.” What did I

command? The Second Platoon of the Anti-tank Company of the

422nd had a compliment of 32 enlisted men and one officer

(me). Three 57mm Anti-tank guns, three 1-1/2 ton trucks, and

one Jeep (my command vehicle).

(The complete roster of my platoon is in Appendix [x] of

this record.)

What did I know about our position and that of the enemy?

Not very much! I had led our Division to St. Vith, so I had

a pretty good idea of the town’s size and location. We had

passed through Schoenberg and Schlausenbach on our way up to

the Schnee Eifel, but not more than that was known to me. I

asked the officer I had replaced if he had any maps of the

minefields in front of us, and he replied they had been laid

sometime before he got into the line, and he was never given

anything as to their location.

I got to know the officers of Company G, Second Battalion,

422nd as we had them dug in around us (see Map 1). The day

was spent in cleaning our Anti-Tank guns and individual

weapons; and estimating the distance to potential targets,

in the event we had to use HE Shells (High Explosive)

instead of APC Shells (Armor Piercing Cap). APC Shells were

not too bad against heavy German Armor (Tigers and Panthers)

if fired from an angle (See Report of 776 Tank Destroyer

Battalion in Appendix [xi]). As I have pointed out, we were

armed with three 57mm Guns. A muzzle diameter of 57mm is a

little less than 2-1/2 inches.

(See Appendix [xii]). It is a small bore, compared to the

90mm the German’s used. The British version of the 57mm was

called the “6-Pounder AT Gun” (it had a “Crown” etched into

the top of the gun’s Breach). We did not bring our own guns

from the states, we were supplied with the British ones when

we arrived in England.

I awoke on the morning of December 16th with a shock. Sounds

carry across open areas, and the sounds I heard coming from

the north of my position were of tanks and artillery. The

2nd Division had laid telephone lines, and we had connected

to them. A call came in from company headquarters (CO HQ)

alerting me to enemy action to the north of us. How do you

spell adrenaline? Mine was pumping. I told Sergeant Phillips

to alert the men and to take up gun positions in the event

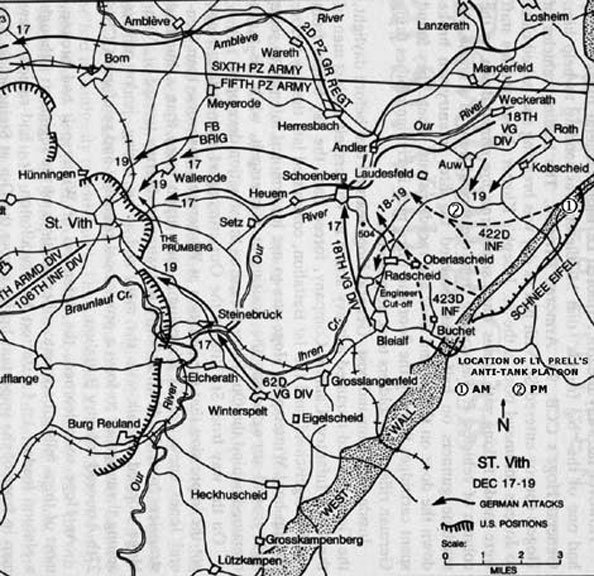

of an attack. (See Map 2)

MAP 2 15

By late that afternoon the sound of artillery was coming

from the north, west and south. It was strange, as nothing

came from where the Siegfried line lay just east of us. Then

I received a call from CO HQ: “the Division is under heavy

attack from both the north and south, so the 422nd will be

pulling out in the morning (December 17th) and moving to a

position where it can protect the northern flank of the

Division.” We were to move in an arc to the rear, using my

platoon as the pivot point. (See Map 3).

MAP 3 16

You may want to return to Page 12, and reread the section of

Colonel Slaydan’s Diary, dealing with December 17th. Then

read the following quotation from a memorandum written

(September 25, 1945) by Colonel Joseph C. Matthews,

Regimental Executive Officer of the 422nd during the Battle.

From: Lt. Col. Joseph C. Matthews AG & SF RS Miami Beach,

Florida 25 September 1945 Memo to: Former Members of the

422d Inf:

1. Purpose. This bulletin is an attempt to furnish you with

the available information on casualties, awards, etc.

pertaining to the 422d Inf. and to bring you a message from

your former Regimental Commander, Colonel Descheneaux, who

is hospitalized in Fitzsimmons General Hospital, Denver,

Colorado, as a result of tuberculosis, which he contracted

while a POW. Please make this bulletin available to any

former 422d men who may be near you.

2. Summary of Combat Operations. The 422d Inf. went into

combat in the Schnee-Eifel Area of Germany on 10 December

1944. On 16 December, the regiment was hit by the German

Ardennes counter-offensive, and was quickly cut off. Several

sectors of the regimental zone received heavy artillery fire

and ground attacks, all of which were repulsed. Co. "L" and

CN Co. counter-attacked towards AUW on the afternoon of 16

December and prevented the Regimental CP, AT Co. and Cn Co.

areas from being overrun. On the night of 17 December, 2d Bn

was swung around facing north, to meet a threat from strong

enemy forces which had outflanked us.

On 18 December, orders by radio from Division Headquarters

directed the 422d Inf., in conjunction with the 423d Inf.,

to attack and destroy enemy forces at Schoenberg, and

continue along the Schoolbag St. Vith road and clear the

enemy from that road, which was originally our principal

supply route. Meanwhile, the 7th and 9th Armored Divisions

were committed in the vicinity of St. Vith, where the 106th

Div. CP and other installations had been located, but they

were unable to stop the German drive at that point.

The 422d Inf. made an extremely well executed cross-country

withdrawal during the day and night of 18 December, to

assembly position southeast of Schoolbag, and attacked

towards Schoolbag on the morning of 19 December. They

quickly came under small arms and artillery fire from

several directions, and the 1st Bn, on the right, was

attacked by tanks and part of the Bn was cut off and

captured. The 2d and 3d Bns continued the attack towards

Schoolbag and came under intense fire from several types of

weapons of a large enemy antiaircraft unit, which inflicted

heavy casualties and knocked out a number of our mortars and

machine guns.

The 423d Inf. on our left had sustained heavy casualties,

was badly disorganized, and later was almost entirely

captured or surrendered.

In the afternoon of 19 December, having had no re-supply of

food or ammunition, or evacuation of casualties for the past

four days, Colonel Descheneaux decided to surrender that

part of the regiment. Parts of the 1st Bn, Co "G", Co "H",

and men from other units found their way to the Regimental

Motor Park, and held out until 21 December. Co "L" escaped

almost intact through the German encirclement, and moved

west, but ran into enemy positions on the night of 20

December, and were captured after sustaining many

casualties. The majority of the vehicles and personnel of

Regt Hq Co, AT Co and Cn Co, which had remained in the

assembly area, tried to force a way out to the west, but ran

into mine fields and artillery fire and were captured or

surrendered. All of the regiment was killed or captured

except 9 officers and about 70 men. The regiment was

re-constituted in France on 10 April 1945, and has since

rejoined the 106th Division.

If you noticed on Map 1, the 1st Bn (including Co “G” and Co

“H” were at about the same location as my platoon, when the

battle began. On the morning of the 17th they began moving

out. My Platoon stayed in position for at least an hour and

then we began to pull our guns out of their emplacements.

Our move west started at noon. It wasn’t long before we

reached the tail end of the column. It was slow going and

after several miles we were ordered to dig into positions on

the north facing side of the road. The men “bitched” like

hell, having to dig into almost frozen soil, but they did

the job, and we settled in for the night.

All the time, the sound of tanks, machine gun fire, and

artillery fire, but so far nothing aimed at us. In the

morning of the 18th, I could see enemy tanks and trucks

moving on a road, along the ridge north of us. The distance

wasn’t all that far, and if I had been given the order to

fire on them, I knew my guns would have been effective. But

soon the units of the 1st Bn began moving west again. I was

contacted by my Company Commander, and was told that the

Regiment was moving toward Schoenberg, which was under

attack. Also that the 7th Armored Division was on its way to

relieve our Division. I was to remain in position until I

received further orders. This made no sense to me as I would

be separated from the rest of the regiment. We were about

where the 2 in the circle is shown on Map 3. For several

days now my men had been eating “C” rations heated on the

cylinder blocks of their trucks. We still had a lot of “K”

and “D” rations in case we needed them. (See Appendix [xiii]

and [xiv]). It was cold, cold, cold.

On the morning of the 19th, I tried to radio Co.HQ, with no

success. I sent Sgt. Phillips in my Jeep to see if he could

make contact with the 1st or 2nd Bn or with our Co HQ. An

hour later, he returned to inform me that the road running

south from AUW (see Map 3) was a sea of German vehicles

moving south. In plain English, we were cut off from the

rest of our Regiment. Phillips said he had met up with a

member of the 2nd Bn. who told him our regiment (422nd) had

surrendered. Well wasn’t that just too much to stomach. Here

I was, out here all alone, still hadn’t fired a shot, and we

have been told the 422nd had surrendered. I can’t contact

anyone by radio. What the hell, am I supposed to do? Our

57mm guns were still dug in (somewhat), and we could see the

enemy on the far ridge. I told Sgt. Phillips, I’d be damned

if I was going to be in this war and not fire a shot, so I

instructed him to have the gunners, go after the vehicles

moving along the road on the far ridge. A moment after we

began firing, the Germans started shelling our position. One

of their rounds hit a tree showering us with shrapnel.

Several of us were hit, luckily no one was seriously

wounded.

I called my four Sergeants together, and we agreed the

situation was hopeless, unless we gave up trying to be an

Anti-Tank Platoon, and instead became a Rifle Platoon, and

got the hell out of there.

It didn’t take long to remove and ditch the breach-blocks of

our three 57mm guns, and to disable the vehicles. (See

Appendix [xv]). “Light packs, take only “K” and “D” rations,

and a single bandoleer of ammunition…we move out in ten

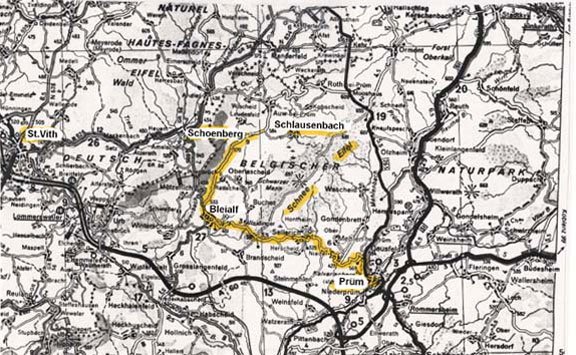

minutes.” I felt we should stay off the roads, and move west

(cross-country) toward Schoenberg. After the war, I was to

learn, it hadn’t mattered which way we traveled, and sooner

or later we would have run into elements of the 18th V.G.D.

(Volksgrenadier Division).

It was now afternoon and we were moving slowly through what

was wooded, then open, then wooded, terrain. Tec5 Fielen and

I out in front, followed by the First Squad in a wide

Skirmish Line, then the Second and Third Squads in wide “V”

formation, with Sergeant Phillips in the rear.

Light snow was falling, and it was not only very cold, it

was beginning to become dark. Fielen and I were moving up a

slope (in the open) when someone shouted something in

German, followed by shots from an Infanterie Waffen

Sturmgewehr (Infantry automatic rifle). (See Appendix

[xvi]).

Before we could drop to the ground several of my men were

"cut-down" by this gunfire. After we did drop to the ground,

we were then “hit” by what seemed to be a hundred

flashlights beamed at us. Well, maybe not hundred, but to me

it seemed like a hundred. I had led my platoon into a

bivouac area occupied by a German Engineer Company. Lucky

for us they were an Engineer outfit and not the SS (or even

Combat Infantry). At the time I wasn’t sure who was more

afraid…we or they…? I was sure that there was no way out. We

stood up holding our hands high above us…and they accepted

our surrender. Three of my men were dead and four others

were wounded. Those of us who were not wounded were taken to

a nearby road (it turned out to be the road running south

from AUW (See Map 3) and from there, we were marched to

Bleialf and on to Prüm (See Map 4).

(Note: When doing research on the Battle of the Bulge, I

learned that the Engineer Company was probably part of the

1818 Engineer Battalion, 18th Volksgrenadier Division

commanded by Oberst Hoffman-Schonborn. The 18th V.G.D. was

part of the Fifth Panzer Army, commanded by General der

Panzertruppen Hasso von Manteuffel. Yes, very lucky for me,

because just north of us was the German Sixth Panzer Army,

commanded by Oberstgruppenfuhrer der Waffen-SS Josef

(“Sepp”) Dietrich. Under Dietrich was General Priess,

commanding the 1st SS Panzer Corps. And under Priess was the

infamous Kampfgruppe Joachim Peiper, commanding one of the

1st Panzer Division’s Panzer regiments.

Quoting from A Time for Trumpets, by Charles B. MacDonald

(New York: William and Morrow and Company, 1985):

Peiper received his orders for what his superiors called

"the decisive role in the offensive" three days before the

start of the attack from the commander of the 1st SS Panzer

Corps, General Priess. In the course of the briefing, Priess

passed along an order of the day from the Sixth Panzer

Army's commander, General Dietrich, which reflected Hitler's

exhortation to his senior commanders at the Adlerhorst. The

offensive represented "the decisive hour of the German

people" and thus was to be conducted with "a wave of terror

and fright" and without "humane inhibitions." As Peiper

himself later recalled the order, the German soldiers were

to be reminded of "the innumerable German victims of the

bombing terror." He was also "nearly certain" that "it was

expressly stated that prisoners of war must be shot where

the local conditions of combat should so require it."

Although that proviso was incorporated into the

Kampfgruppe's order for the attack, Peiper himself made no

mention of it in his oral briefing to his commanders, for

they "were all experienced officers to whom this was

obvious." The word to kill prisoners nevertheless reached

almost all subordinate units. One company commander enjoined

his men to "fight in the old SS spirit," and added: "I am

not giving you orders to shoot prisoners of war, but you are

all well-trained SS soldiers. You know what you should do

with prisoners without me telling you that." A private

recalled that not only were they to take no prisoners but

"civilians who show themselves on the streets or at the

windows will be shot without mercy."

One noncommissioned officer urged his men to think of the

thousands of German women and children buried in the rubble

of German cities; then they would know "what you as SS men

have to do in case you capture American soldiers." The

offensive was aimed at "the murderers of our mothers,

fathers, and children." Prüm turned out to be a collection

point for those members of the 106th who had become POWs. On

the morning of December 20th, we began a march of 10 miles,

to the town of Gerolstein, where there was a railhead. This

was to be our introduction to what were known as “Forty and

Eight” (forty men or eight horses), boxcars from World War

I. (See Appendix [xvii]). The German guards counted us out

into groups of sixty (not forty) and loaded us into these

broken-down boxcars. As I remember, there were at least 25

boxcars, all lined up behind an antique engine, which was

ready to pull the lot into Germany.

If I were to choose to chronicle the “one-week”, which had

the greatest effect on my life, the week of December 21st to

28th would be, that week. To describe the events, the

emotions, the interpersonal relations, and the shear

enormity of what occurred, would fill a book. Father

Cavanaugh, our Regimental Chaplain, wrote an account of that

week and rather than copy it in detail, I will attach his

story to this record. The following is my account, very

brief and I trust unemotional___ _ As soon as our group of

“60” had been loaded into a boxcar, it became apparent that

everyone would not be unable to sit down at the same time.

Someone shouted “I am a Lt. Colonel, does anyone outrank me?

If not, I am in charge.” No one did outrank him so he took

over. He had us “count off” and after being assigned

numbers, he had the “odds” sit down and the “evens” stand.

We were to all stay clear of the sliding doors, where there

was a slit where one could relieve one’s self, when the need

arose. We took count of how many canteens of water and field

rations we had with us. (I had a canteen of water and two

“D” rations. Some of the men had no water and no rations).

This was a group of 60 officers and enlisted men, all from

the 106th Division. The highest rank in this boxcar was a

Lt. Colonel. In addition we had several Majors, Captains,

and Lieutenants. Closest to me was the 422nd’s Chaplain,

Father Paul Cavanaugh (a Jesuit priest from Cleveland,

Ohio).

Sometime later that day, with a series of lurches, the train

moved off on its journey into Germany. With frequent stops

and starts the train moved east, and every two hours those

sitting exchanged places with those standing. Strange as it

may seem, there wasn’t a lot of conversation. It was only

after the war that I learned, this was the coldest winter

ever recorded for this part of Germany.

It took two days to cover the 68 miles from Gerolstein to

the railroad yards in Limburg (a town 22 miles east of

Koblenz). It was late in the afternoon when we arrived in

the Limburg marshalling yards. The guards began opening the

boxcars one by one, allowing the occupants to jump down and

relieve themselves, before being forced to climb back in the

cars. I was in a boxcar toward the end of the train. As you

will discover, the events soon to take place, delayed until

the next morning, the opening of the door to my boxcar.

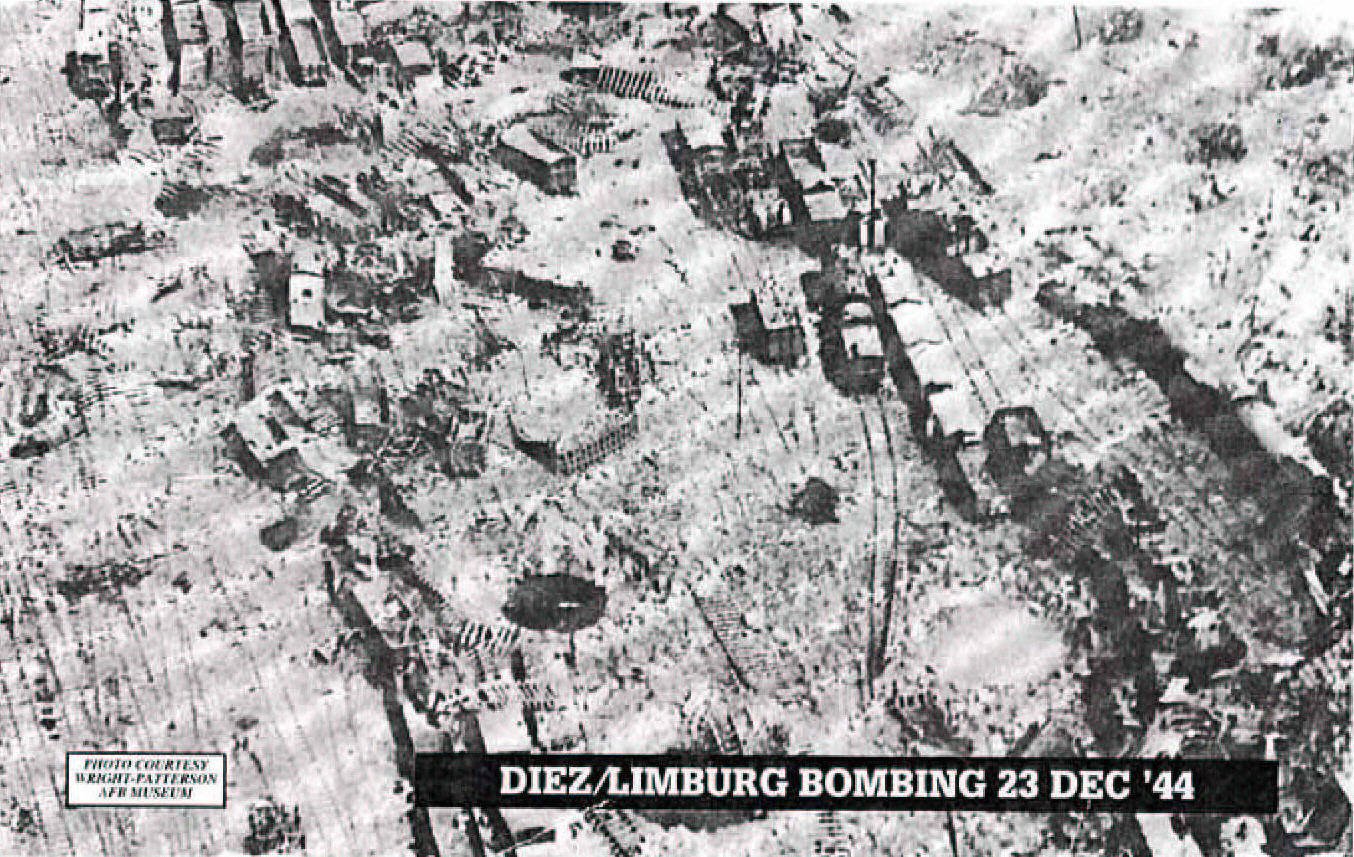

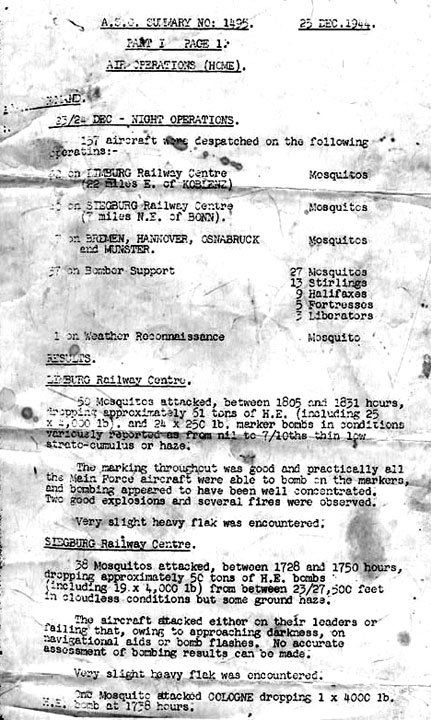

A summary of what happened is described in a RAF Report,

(See page 24). As darkness fell, so did 61 tons of bombs,

dropped by a flight of 50 RAF Mosquitos.

No one had bothered to inform the RAF that at 1805 hours on

the 23rd of December, some 1400 Officers and Enlisted men

from the 106th Division would be in boxcars in the middle of

the marshaling yards in Limburg, Germany. The bombing proved

to be quite accurate. (See the Photograph “Bombing 23 Dec

‘44” in Appendix [xviii]).

Report of Air Night Operations, over LIMBERG Railway Centre,

23/24 Dec. 1944.

The bombs came down with shrieking sounds, and as they

impacted around us, all I remember is Father Cavanaugh’s

total calmness. It was all over in minutes, but at the time

it seemed like an eternity.

East of Limburg we were loaded back into a new set of

boxcars. During the trip to Bad Orb, we spent Christmas on

the train. Then marched up the hill to the prison camp IXB

at Bad Orb. Here the officers and enlisted men were

separated from one another. We were given a POW number; mine

was 25563. After a short stay, the officers were moved 20

miles east to Oflag XIII-B, near Hammelburg.

Of all my memories dealing with the war, the most difficult

for me to bring back into consciousness are the months

during which, I was a Kriegsgefangen (POW) in

Oflag XIII-B, from early in

January, 1945, until March 27th. Again I refer you to Father

Cavanaugh’s account. Although some of my recollections

differ from his, overall his description of the camp and

events are valid. (See page 96, 1/2 way down.) On March 27th

a small force of US troops liberated the camp. This event

has been the subject of several books, not only because the

objective of the exercise was to release General Patton's

son-in-law (Lt. Colonel Waters) from the camp but also

because the “Raid” (as it has been called) came to such a

disastrous conclusion.

"48 Hours to Hammelburg" by Charles Whiting (New York:

Ballantine Books, 1970) "Raid! The Untold Story of Patton’s

Secret Mission", by Baron, Baum and Goldhurst (New York: G.

P. Putnam's Sons, 1981) Of course, to his dying day, Patton

denied having ordered the assault to free his

son-in-law...... but those of us in the camp know the first

words of the Officer in charge of the Task Force were:

"Where is Colonel Walters"......! Patton told reporters

(when asked about the affair) that he ordered the raid as a

diversionary tactic.

The American POWs were given the choices of (1) climbing on

the tanks and riding out on them, (2) staying in the camp

and waiting to be freed, or (3) taking off cross-country on

our own, trying to work our way to the American lines. It

didn’t take more than a minute for me to make my choice.

I and two other Kriegies gathered our meager belongings and

took off cross-country (no way was I going to ride out on a

tank....and no way was I going to stay in the camp). (At

this point, Father Cavanaugh and I went our separate ways.)

We three tried to work our way southwest from the camp.

After several days we had made good progress, and were

hiding in a wooded area a few hundred yards from a

farmhouse. Tired and hungry, we drew “lots” to see which of

us would visit the farm to try to find some food. It was at

the break of day when the “chosen” one took off, skirting

the field, between us, and the farmhouse. About an hour

later, three German soldiers came up behind us, and we were

POWs again.

We were separated from one another and in Würzburg, I was

put on a coach train (with a Lieutenant as my guard) for the

fifty-mile trip to a camp at Langwasser, a short distance

south of Nuremberg. My guard was most cordial, giving me

his name and address, so that we might be in contact after

the war had ended.

The Camp was Stalag XIII-D -- Oflag 73 (for photographs and

a description of the camp log onto:

http://home.t-online.de/home/RIJONUE/stalag.htm) Within

a day after arriving at this POW Camp, I became ill, and was

sent to the camp hospital. I was kept there by an Australian

doctor, while most of the POWs in the camp were "force

marched" away (toward the east). A week later (mid- April)

the German guards, just up and disappeared, and we were able

to walk out of the front gate. The Australian doctor and I

commandeered a motorcycle from a residence near the camp (I

gave the owner a receipt from the US ARMY) and we took off

going west (for, maybe a few hours) until we found troops

from an American Armored Division. We were given some food

and “petrol” and we then took off for Paris. At the time we

were riding the motorcycle away from the camp, the

Australian told me Russian POWs were in a nearby camp, and

that if they got loose, there would be one hell of a riot. I

learned later (after the war) when the Russians got out they

more than just rioted, they created mayhem.

From Paris, I was sent to Camp Lucky Strike and on May 6th,

I boarded a hospital ship, which arrived in New York on May

the 17th (we were at sea when we were notified the war in

Europe was over, VE Day, May the 8th). You can imagine the

reception we received upon our arrival in New York.

http://www.skylighters.org/special/cigcamps/cigintro.html

The day after arriving in New York, I was assigned to a

Rehabilitation Center, located at the Biltmore Hotel in

Montecito, California. I was allowed one week of “delay in

route” before reporting to the Rehab-Center. The rail trip

to the Los Angeles train station seemed as if it took

forever to get there. Arriving in the late afternoon, I was

met by my father. After a strong embrace and a series of

hugs he asked me if I would like to do anything before going

home. "Yes", I said, "could we stop by the Pacific Dining

Car and have a New York cut steak?". We did and of course I

couldn't finish it, but oh (!), did it taste, ever so

wondrous.....what a way to begin the task of erasing the

memories of Hammelburg.

At the Rehab-Center all they did was feed us. In the Lobby

they had installed several large refrigerators filled with

cold cuts, milk, and all the makings of a “Dagwood

Sandwich.” By the end of the month, after gaining back the

weight I had lost (twenty or more pounds) I was reassigned

to the Headquarters of the Infantry Replacement Training

Center (IRTC) at Camp Hood Texas. I took my brother Melvin’s

1939 Ford, and drove it non-stop from LA to Killeen, Texas

(50 miles southwest of Waco).

The IRTC was training Infantrymen for the planned invasion

of Japan. I don’t know why, but instead of assigning me to

some Anti-Tank field outfit, the officer interviewing me

asked if I would like to work for Lt. Colonel Howard. L.

Shinaberger, the Camp’s Adjutant General. “Oh, yes Sir,” I

replied and the next day, I had a new rank, and a new title:

1st Lieutenant Donald B. Prell. Asst. Adj. Gen. (Assistant

Adjutant General).

What did I do for the next few months…..not very much. Every

morning the first thing I did (after having breakfast and

then morning coffee) was to sign the Daily Bulletin before

it was “mimeographed” and distributed to all units of the

IRTC.

Then after another morning coffee, I had my driver take me

in my Jeep to inspect training. After lunch in the Officer’s

Mess, I would return to my office, where I was required to

sign all sorts of important orders and other documents,

which could only be executed by someone as important as I

was.

When the war in the Pacific ended (VJ Day, August the 14th)

the need for training Infantrymen for the invasion of Japan

also ended. The Camp’s Adjutant General and its Asst. Adj.

Gen were now set to work, closing down the IRTC at Camp

Hood, Texas. It took us a little over four months.

On November 26, 1945, I was given my “Separation” physical

examination. (See Appendix [xix]). It showed that I had

shrunk to a height of 61 inches. In the remarks section it

was stated: “Anxiety state mild. Manifested by nervousness

and tremulousness.” Now I ask you, wouldn’t you have all of

that, if you were taking a physical to get out of the

service? Yes, I still had my flat feet, and everything else

was “Normal”.

On January the 7th, 1946, Lt. Colonel Howard. L. Shinaberger

signed my discharge papers (See Appendix [xx]) and I signed

his papers. After exchanging documents, and saluting each

other, we officially closed the IRTC at Camp Hood, Texas. It

later reopened as Fort Hood, home of the 1st Cavalry

Division.

My military career hadn’t quite ended, then and there, as I

soon joined the Army Reserves, and remained in the Reserves

until 1960. At that time I was the ranking 1st Lieutenant in

the US Army Reserves (I had been a 1st Lt. for 15 years). I

was informed I had to become a Captain or I would need to

retire.

Not wanting to take on the tremendous responsibility of

being a Captain, I choose to leave the service. My papers

are dated 29 January 1960 (See Appendix [xxi]).

No doubt this report is wanting, there were so many events

and “vignettes” I have omitted. The chance meeting of Bud

Mittenthal, Mort Granas and I at Fort Benning, in June of

1944. The payment of $1.00 to the enlisted man offering me

my first salute (after receiving my commission). And on and

on and on………..

|

Page last revised

04/21/2018

Page last revised

04/21/2018 Page last revised

04/21/2018

Page last revised

04/21/2018