|

A Tale By

Pfc. Charles D. McMullen ODYSSEY OF A “KRIEGIE |

|

Foreword

Therefore, I want to dedicate this story to some other people in our family that served in the service our country . This goes back to the Revolutionary War where Joseph Cheuvront a French citizen and Junes Great, Great, Great, Great Grandfather fought for the colonies and for which he received 200 acres of land in the Good Hope area of what is now West Virginia. Junes father who served in WWI on the ship that brought the WWI “UNKNOWN” soldier to the U. S. and, her brother Charles who served in the Pacific during WWII, her twin brother Jack who served in the Korean War, my brother Art who served in the Pacific during WW II and my uncle Red who served in both WWI and WW II , and last but not least my uncle Hub who served in WWI

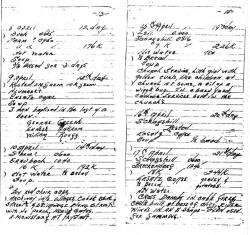

My prayers are that the situation will never require the wholesale recruitment of our sons again. It’s a prayer and a dream that only time can answer. After 50 years of not wanting to talk about my WWII experiences I am now trying to sort out all the things I remember and integrate them with information I can gather from others whose experiences were similar to mine.

I decided to put a review together for my children and my grandchildren. All these years I have not talked much about that period of time in my life. They were not the best years. A local friend of mine from the 423 Regiment had a short article in the paper about his being a POW and while we knew each other at Rotary we didn’t know of the others POW experience. I gave him a call and he gave me the 106 th. CUB “E”-mail address. I proceeded to contact the CUB and Sgt. John Kline to see what information was available. It so happens that there is a wealth of info out there. Among the information he had were the names and addresses of 22 people from the 422 Anti-Tank Co. in which I was serving when I was captured. I tried to forget for so long and time has taken it’s toll on my memory so that I sought out this additional information. In addition to the 22 names I also found 8 more on the Internet by doing a “search” by name.

My first year and a half in the Army was not very exciting and I’m going to leap frog to the spring of 1944

I joined the 106th Infantry Division in August of 1944 when the large group of ASTP, Air Corps, etc people came along for replacements for the replacements who had been pulled out of the 106 th to replace the losses after the invasion. I left ASTP in the spring and was stationed at Malden Missouri as a Qualified Air Cadet waiting assignment to a class when I was notified to report to the 106th (ASTP was the Army Specialized Training Program which sent people to college and who would become officers after their 2 year college program. In return for your education you were to serve 2 years after the war ended. ). I was stationed at Camp Atterbury near Indianapolis until we moved out and went to Camp Miles Standish, an area near Boston and then onto the ship. I sailed on the “Aquitania” on 10/21/44 and we arrived in Glasgow on 10/29/44. Actually the docks are in the bay a little further at Greenock.

I picked up a truck and we drove to an area near Oxford, England. It was a little town called Fairford. I think I remember an estate of a family named Palmer where we had our Motor Pool and possibly headquarters of some sort. I'm told it was torn down because the Americans ruined it. Here I spent my third Thanksgiving away from home and ate it in the rain in a pup tent.

The next move was at the end of November when we went to France on an LST. This led to a period of time in a pup tent with rain and mud also, my first taste of “Calvados” and my last.

Next it was the time all of us had all been wailing for. I don’t remember too many details other than talking to the guys we relieved and being reassured that things were quiet. We had our 3/4 ton and 57mm. anti-tank gun with a minimum of ammunition. We got some ammunition from the 2nd. Div. people that we relieved This included 57mm and . 30 cal. for our rifles.

We were on the “Siegfried Line” in an area called the Schnee Eifel and there was a concrete bunker with metal bunks similar to those on a submarine. (without mattresses) When we were not on duty we spent time in the bunker. At night for entertainment we listened to the “buzz bombs” clear our area a couple hundred feet in the air on their way to England. They had those loud noisy ram-jet engines aimed at London.

This next thing is hard to believe! We took the battery from the truck and jerry-jigged a light in the bunker. It didn’t take too long to realize this was not a good idea for more than one reason. So Sgt. Weigert and I took the battery up to the truck and were in the process of reinstalling it when we saw movement in the woods. As some one would move between the trees they would block out the snow. I would say they were about 100 yds. away. I don’t know exactly how it started but I was on one side of the truck and Sarge was on the other when somebody started shooting at someone , about a half dozen rounds and it was all over. The irony of this little tale is the fact that Sarge said that it bothered him to shoot at them because he was concerned that they may have a wife and children at home like he did. This same guy was killed at the Limberg rail yards during the air raid on the yards , he was out in open directing people to cover.

Back at the front the next thing of import was the chow jeep didn’t show up. Then we were ordered to get ready to move out.

I really don’t remember “moving out:” but I do remember seeing German troops 500-600 yards away crossing a big field, it was cloudy overhead and there were P-51 trying to strafe them. They were going in a parallel direction to the road we were on.

Some time later I remember being in a long column on the side of a long hill in the middle of a convoy. this is were they started to pick off the vehicles with their 88’s. They were weird sounding. You heard whom, , whom. One whom was the firing and next was the shell exploding, almost simultaneously.

(Lt. Parker in his letter Says” we were captured in the village of

Bleilf on December 19. Our situation was quite hopeless.

We hadn’t been fed for two days, we were out of contact with Division

Headquarters, we had no idea were the Germans were , we were low on

ammunition and our long column of Jeeps and trucks was caught on a narrow

road with no possibility of maneuver. At that point we ran into a

German armored column and it was clear we could go no further. Our

company Commander tried to find a way out by a side road but ran into a

mine and we decided that road was no good. We were surrendered

by Capt. Foster of Regimental Headquarters” Lt. Parker states

this was the largest unit surrender in Army history with the exception of

Bataan and Corregidor . He was interviewed about ten years ago by an

inquiry into what happened. Lt. Parker said it was

a humiliating experience and most of us felt we should have done more

fighting. However, we did our duty and followed out

orders to the best of our ability. Nobody turned and ran. Lt. Parker Quotes Talleyrand a French foreign minister who replied “Madame I survived” when asked what he did during the Napoleonic period. That's what we did and I wouldn’t have any grandchildren to write to if we hadn’t and for that I thank God)

Of course you know what happened next, “For you the war is over”. The word came down that the column had been surrendered. This next incident is my remembrance that some of us were prepared to disable the gun and the truck, however, we were told not to do so. It is also my recollection that someone tried to break his rifle by hitting it on the truck and in doing so the rifle discharged and hit him in the thigh.

Then came confusion.

Lt. Parker states “we were herded into a Churchyard for the night and then marched to Gerolstein the following day. The best estimate is that this was a 30 mile march. On the 21st. we were loaded into box cars and off we went to Limburg and Stalag IV B”. Lt. Parker could have been routed differently, as my recollection was we walked to Limberg and Stalag XII A , then loaded into box cars . No big deal but illustrates why I sought others experience. I have stories telling both versions.

I'm not sure how the walk to Stalag XII-A actually started, however, 1 do remember the WALK. I never received Combat Boots (some problem with size or whatever) and along the walk I was unfortunate enough get my feet wet. I was trying to get over a small stream that we thought we could jump. Both of my feet were frozen , the right more so than the left. I didn’t lose any toes but I did lose the toe nails on two toes . Later I made little booties for my feet as they pained and I tried to keep them warm when I slept.

I thought this was it I I was tired , hungry, cold, weak, feet frozen and I didn’t know if I would be able to make it. I was never a big church goer but I knew how to pray and I did ever foot of the way. That spiritual help and the physical help from someone in the group that helped me when it really got tough enabled me to make it . 1 don’t know who he was, just one of many who was able to help and did. I don’t know how many times I asked for strength to go one more mile and it came and I made it. Every time I got to the point I didn’t think I could go any further this G. I. would help me along . 1 knew what the consequences were if I fell out but there were times that I would have done so if it were not for this other G. I.

The next remembrance is being locked in the box cars at Limburg during the 12/23 air raid. Somehow we got out of our car and started running. This is where Sgt. Wiegert was killed trying to help others by opening cars and directing foot traffic.

The box car ride to Stalag IV B took 8 days . It was cold and, especially so after we (the Americans) got approval to remove some of the horse manure from the car at a stop along the way. We “city boys” didn’t realize how many BTU’s there were in a pound of horse manure. I remember singing Xmas songs on Xmas eve along the way , and of course “White Xmas” brought the tears.

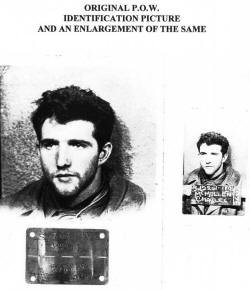

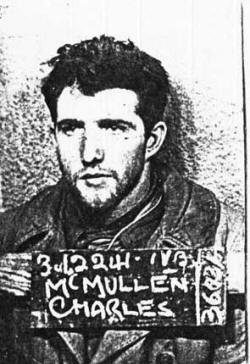

My recollection is that we arrived at IVB late at night and that my I. D. picture was taken about midnight. I obtained this picture later on when the Russians took over at Stalag III-A. Someone had obtained all of the I. D. pictures and passed them out. I still have it and my “Kriegie” dog tag. I posed as a non-com and was processed as a non-com and went to a non-com camp. Several of the others ended up in work Kammandos since Privates could be made to work. In particular Louis Tarantino and Francis McHugh talk of their experiences.

IV-B

gave me my

first exposure to long time POW’s. The English, Aussies,

Canadians , etc. had been prisoners, some for long times and

had learned to adapt and control the situation to the best of their

ability. They had control over their people and maintained

discipline . They had price control on how many cigarettes this or

that should cost , you didn’t steal from your buddies, etc. I

saw one fellow carrying a sandwich board sign that said ”I am a thief’.

He had to wear it given number of days as punishment for stealing.

Most of them had some sort of endeavor that they spent time on. I

met a lad from London who taught Algebra to others. They put on a

great New Years show with music, some guys in drag singing and dancing.

As to their Price Control we Americans took care of that by paying too

much for every thing until they became angry. The trip to Stalag III-B is cloudy in my mind. I remember the SS loading us into cars and I was hit on the head with a rifle butt because the people ahead of me were not moving in fast enough. I can’t think of any thing else.

At III-B I think I remember the dogs being let loose in the compound during air raids. That is everywhere except the “Mongolian” compound since the dogs would disappear.

I remember leaving III-B in a hurry at night about the middle of February. The Russians had moved to the Oder River and the Germans were going to try and make a stand there. I do remember one of the guards , who looked like “Schuitsy” on the TV show. He was a Home Guard about as old as my (grandfather. He stood at the door with tears in his eyes and shook our hand as we left the barracks. I'm not sure if he was sorry to see us leave or that he was sorry he would have to fight the Russians the next day.

The trip to III-A is also confusing in my mind. As near as l can tell this was a 100 mile walk. I know we walked but I also seem to remember some time in a box car. I remember sleeping in a school one night, another night we slept in an enclosed farmyard and someone stole a glass egg from a chickens nest. I thought someone was going to be shot over that damn egg. It appeared and we went on our way. I remember going though a small village and people lined the road. It was here some of the future German SS in their black cub scout uniforms threw sticks and rocks at us and an occasional spit. These were little cub scout age kids, the standard knife in their boot and all.

It

was on this

walk we passed a column of “Jewish” prisoners in their flimsy black and

white stripe pajama uniforms , wooden shoes walking in the cold , snow on

the cobble stone road. The last man in the column would be hit on

the back with a switch as they walked along. Since this would

take its toll after a while they exchanged places. A short lime

after we passed we heard a rifle shot and assumed that one of them had

fallen out of line or something comparable and he was shot. In doing research for this article I found a similar story in a book “We were each others prisoners” which was collection of interviews of both American and German prisoners of war. It’s an interview and storey of a George Rosie . He was captured at a different time and place . However, from the time he arrives at Stalag 1VB and to the end our paths were the same . Same camps , same walks , etc. The difference is he had a 148 page diary available and is able to fill in a lot of detail that I don’t remember but which I recognized when I read his story. His story is attached and this would be a good time to read it to maintain continuity of my story. It’s titled Attachment 1

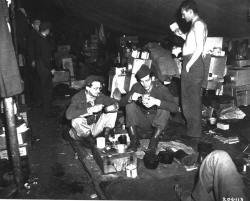

Finally we got to III-A and they had a full house in the barracks. So they put up some more wire and enclosed a tent area. They put up 7 carnival or circus type tents side by side. I think there were 400 to a tent and 7 tents. We slept on the ground and each person had a space about 2’ by 6’ for his “condo”. There was limited water available for the group at the end of the tents, all outdoors. The personal facilities were typical field latrines, don’t drop your wallet. This was home until the end of April. There were the usual potato, ersatz coffee, and a loaf of bread for 5 or 6 people. I got so upset one day over arguing which piece of bread was mine that from then on! took the last piece, !t couldn’t make that much difference and I became upset with myself for becoming that unrestrained.

As the war progressed and the “Allies”went to 1,000 plane daylight raids we sat in the open “Picking lice” and counting planes as they passed over. Things went the same each day . Lots of “rumors”. The Germans would ask what are you going to do when you meet the Russians? You should have joined up with us , if you had furnished the material and us the manpower we could have ruled the world. Now you are going to fight the Russians. Not quite right but upon review they were close.

Finally the Russians did come. We went to sleep one night and in the morning the Germans were gone and the Russians were in the “Towers”. Naturally things were confused and eventually we found out that the Russians would not shoot if you crossed the warning wire. The next thing there was a hole in the main fence and they didn’t shoot you if you went out. There was no big exodus as we didn’t know what was out there and they were feeding us and there was some control. We heard all sorts of rumors, they were going to hold us hostage, they were going to ship us to Odessa on the Black Sea, which was the wrong direction. One new experience was having a “short arm” inspection by a female Russian doctor, knife in her boots and all.

At this point in time I met a G. I. from Cleveland by the name of “Bill”. He was of Polish extraction, spoke Polish, and could communicate in German and Russian. I don’t know his last name, outfit or anything else. Ironically he is the one I would like to communicate with the most. Neither of us smoked and we had a some “ciggies”. There had been some people go to town and the Russians didn’t bother them , so having no sense and nothing else to do “Bill” and I took off for town with our “ciggies”. We bought food such as bread , potatoes, garden veggies, most any thing we could find. ”Ciggies were money and we bought “low” and came back to camp and sold “high”. We did this a couple of days and accumulated a small fortune in “ciggies”.

The rumors continued to flow and finally we heard of a link up of Americans and Russians at Torgau. After some discussion Bill and I decided to take off for Torgau. We bundled up our “ciggies”and away we went. We got about 15 mile away and were picked up at a Russian check point and they returned us to camp. We continued to be concerned about the rumors and didn’t relish going to Odessa, so we took off again. This time we hailed a 2 1/2 ton Russian truck and with the aid of a few “ciggies”the driver let us climb up on top and lay on the canvas between the bows. Not only did we get through the check point, the driver took us to his Motor Pool and where we were fed and spent the night, “ciggies were dollars!

The next day we headed for Torgau. We were in our POW clothes and I had made a “mickey mouse” U. S. flag from a handkerchief , red fingernail polish and black ink and! put this on my ann. We had our ”ciggies” and were on our way. As you can imagine it was slow hitch hiking so that left us to walking in Russian held German territory in a POW uniform looking for the American Army. I had grown a goatee and mustache and I had lost about 40 pounds which made my uniform look like it belonged to my big brother. About that time two Germans came along riding bicycles and we proceeded to confiscate them. They started to object until we explained the facts of life to them and road off into the morning sun.

We rode on down the road heading for Torgau and we came to a town named Wittenberg and were hailed by some non-Germans and non-Russians. They were two French couples who had been working in Germany as “Slave Labor” and were now trying to get to their home in France. They knew where to get some horse meat and we had the good old “ciggies”so we went shopping. We got some meat , bread, beer or wine and had a banquet that night. They wanted us to help them get home so we took some photos they had of themselves and wrote on them that they had befriended us and to give them any assistance available, and then signed the photos Pfc. C. D. McMullen. Some G. I. probably shot them the first time they showed them to anyone. They told us that there was also a “link up” at Dessau and it was supposed to be closer. O. K. lets go to Dessau.

They were right and the next day we riding our bikes in Dessau when we saw a couple of G. I. ’s in a Jeep. We screamed and hollered and peddled like hell until they finally saw us. Their Colonel had crossed the river to meet with his Russian counter-part and was in a meeting. Their Colonel finally showed up and we were on our way home. This was an M. P. outfit and they treated us great. Anything we wanted to eat and all I wanted was fresh baked bread, peanut butter and cold milk. The next day we got some food that was a little heavier. This was May 4 1944 Big Day!!!!

They had some German prisoners under their control and I told our people about a German Officer who took my watch when I was in the box cars and I wanted to get one from their prisoners. They took me to an area where there were about 75 prisoners and I told them my story and I finally convinced one of them to give his watch. I also got a camera , a pistol and a sword. Some American officer convinced me to give him the camera and pistol. I got the watch and sword. I brought them both home and still have the sword, the watch stopped running about 20 years ago.

From here things started to move fast. They took us to Hildeschein and put us on C-47’s and flew us to Nancy, France . Then the old box car trick to Le Havre with deluxe accommodations only 40 people to a box car. We spent some time in Camp Lucky Strike to try and put weight on us as fast as possible. I actually saw Gen. Eisenhower and a couple of Congressman who told us they would get us home as soon as possible, but don’t gripe about the accommodations. That brought about the RED and GREEN tickets scheme to see who had a bunk tonight on the ship and it allowed you to put twice the people on board. Sleep in a bunk tonight, you were on your own the next night. That is unless you are able to get both of the colored tickets.

I came home on a Liberty ship and it took us 8 days and we arrived in the US on June 12.

After all this time of thinking of the people at home and what it would be like to see them, I suddenly became frightened and I was reluctant to go home and I stopped in Philadelphia with some G. I. I met on the ship. His mother convinced me to go home, she said that everyone was waiting and were anxious to see me. Half way convinced I went to Pittsburgh and took a Street car from downtown to our house. I still didn’t know what or how anyone felt about the situation, did they think I had let them down, I certainly didn’t feel like a hero. Actually my parents were in the same boat as people had tried to tell them how to act and they were not sure what to do or say.

The way it turned out was we all acted like I had been out of town for the weekend and just got back. We hugged and kissed but no hysteria and in a couple of days it was “de javu”

After 60 days at home I reported to Ashville, N. C. at the

Biltmore Estate for reassignment. The war in Japan ended while I was

there saving me a scheduled trip to Japan. I was on a tentative list

to go as I was 5 points short of

getting out of the Army. From there to Fort Behavior in Washington. Then to Walter Reed Hospital as an M. P. until the 5th of December when I was Discharged.

Back to Pittsburgh and on to W. Va. Wesleyan for a B. S in Chemistry, married a great little co-ed 50 years ago in this May, and we have 4 children, 3 grandchildren.

After reading this you may appreciate why I have been reluctant to let this period occupy my time. I still believe it had an affect on my personality , and it sure made me concerned about failure.

I want to thank Capt. Vitz , LT. Parker, Lt. Prell, Mrs. Alexander, John Kline, Rene Pigeon, Johnie Floyd, Louis Taratino , Francis McHugh, A. C. Oelschig for their assistance in providing information to help me put this together . 1 recieved copies of two diaries, Original US Army photographs, and several books recommended to me , plus the letters with their own personal stories.

I feel a lot better having putting this all together . 1 guess some would call it closure.

Attachments: George Rosie Story Excert from “Diary of a Kriegie” Pictures-Official US Anny Stalag lilA “Tent City” Limberg Bombing 106 CUB GEORGE ROSIE

George Rosie was a rough, tough, yet sensitive American paratrooper who jumped into Normandy on D-Day and was captured just hours later. Although his initial fifty days and final three months as a prisoner were especially challenging, Rosie insists the Airborne's rigid training and iron discipline helped him survive. Shortly after his capture, the Germans marched Rosie and several hundred other American prisoners through the streets of Paris, and then photographed the humiliating event for its propaganda value. Rosie also was on one of the deadly forced marches near the end of the war when the Germans moved thousands of prisoners away from the collapsing Eastern Front. Rosie, who admits he was ashamed of being captured but proud of how he conducted himself as a prisoner of war, is a past president of the 101st Airborne Division Association and has written extensively on his war experiences, excerpts from which appear below. 21

The following story by Rosie is a more detailed report of the long march as he had a diary to help him remember. I wrote my recollections before I read his story and I didn’t want to change what I said nor how I said it. It’s mine.

Things were normal for a couple of weeks at Stalag 3-B, but with the

Russians moving closer, the orders came once more to move out.

On January 31, more than four thousand American NCOs started on a

six-day march. The Germans gave us some old overcoats which

were indeed a blessing, but no one had hats, gloves, or

boots. And it was cold! I mean to tell you it was down around

zero. The guards kept us moving all afternoon and all night,

with three short breaks. We were carrying everything we could,

but it was getting so tough people just started pitching things.

We stopped by some barns about five o’clock the next afternoon.

One POW walked over to an old German woman standing by her fence and

tried to trade a bar of soap for some food. One of the guards

walked up behind him and smacked him in the back of the head with his

rifle butt. He dropped like a sack of potatoes. As

we were marched into the barn, we walked by him but there was no

sign of life. The back of his head was smashed in and he was

bleeding profusely.

That night we slept on hay. In the morning everyone was cold

and stiff as hell. It felt like you were ninety years old.

There was no food. Out on the road German civilians with carts

were evacuating along with us. We took an afternoon break

near a Jewish concentration camp. 22 This was my first

look at so-called political prisoners. They had these

ridiculous-looking black-and-white uniforms hanging on them, and

they were nothing but skin and bones. They looked like walking

skeletons. We saw a guard beat them with clubs. As

we moved back on the road, one guy yelled out, “You lousy,

goddam Krauts. God will get even with you some day.

He will! He will! He will!” That started others hollering and swearing at

the guards. It’s a wonder we didn’t all get ourselves shot,

but they really didn’t pay much attention to us. Further on

down the road we saw Jews digging gun emplacements and trenches.

As we walked by we saw a guard pull a revolver and shoot one of the Jews

who dropped into the ditch. It was a day I’ll never forget.

To this day when I see a photo or film about those concentration camps,

I get sick all over again.

Later that day we took another break, and as the guards were getting

us back on the road we heard a shot. Apparently at the head of

the column one of the Airborne guys didn’t get up quickly enough to suit

one of the guards, so he shot him right in the forehead.

As we walked by, he was lying on his back by the side of the road.

That night we slept in barns, again without food or water. Some of us ate handfuls of snow which really didn’t help much. The next morning we were back on the road, but moving very slowly. Now it no longer mattered how much the Germans yelled at us. We were just too damn weak from hunger and cold to move any faster. That evening we stopped in a small farm community. About thirty of us were put in this one barn. After awhile the old

farm woman came in with what she called her slave laborer who was a young

Russian girl. They gave us a few potatoes and some soup.

The next day we crossed over the eight-lane, Berlin Ring Highway

which was probably the biggest highway I had seen in my life.

But it was completely empty. Not a car in sight.

That night we were split up and again stayed in small barns.

The Germans distributed small cans of cheese, which was the first

food they had given us since we hit the road. The next morning

we met another column of POWs heading for Stalag 3-A. We

received a can of cheese for nine men and a loaf of bread for five.

That night we stayed in a mock village which the Germans had used to train

troops. The wooden buildings were all shot to hell.

We were issued some soup that night. The next morning we got

up early and were given a loaf of bread for four men. The

following day we reached Luckenwalde. They marched us through

the city, but there were very few civilians, and the ones who

were there just looked quietly at us. We were a sad-looking

group. About three kilometers on the other side of Luckenwalde

we arrived in Stalag 3-A. I was told that of the 4, 000 men

who had left Stalag 3-B only some 2, 800 made it to 3-A.

We

were herded into compounds with seven huge circus tents. There

were about 700 men in each of these tents which had straw floors.

There was just about enough room to stretch out and lie down on your side.

We slept very well that night. The next morning we were given

showers and our clothes were deloused. We were told there were

no Red Cross parcels in camp. We were issued a loaf of bread

to be divided among five people. Prisoners were coming into

3-A from all over. Evidently thousands of prisoners had been

on the road either fleeing from the Russians on the Eastern Front or from

the American and British troops in the West. To the left of

our tents were two water spigots, but you never knew when the water

would be turned on. Sometimes someone would discover they

were on in the middle of the night. He would then come back

and inform the people in his tent. Someone would get buckets

and go out and stand in line to get the water.

The guards at Stalag 3-A were mostly in their fifties and sixties.

There was one small guard, probably five feet, two inches,

heavyset, and in his sixties. Every other morning he was

on duty in the tower just to the left of where the water spigots were.

We used to sit there in the morning and watch this little guy with a rifle

slung over his shoulder climb up the ladder to the tower. He

had just one hell of a time. The rifle would keep slipping off

his shoulder, and he’d have to reach down for it. We’d

just sit there and laugh at this poor, little guy, but we also

felt some compassion for him. There was a guard in our tent

who didn’t have a mean bone in his body. He was doing a job

because he had to. He would come in the barracks every

morning, and you could hear his voice echo all over the tent:

“raus mit Euch! Roll Call. Aufstehen! Get up!” Then

the guys in the tent would start mimicking him.

Whenever a new guard came into the compound the guys would check him out.

Somebody would stand behind him and say something very threatening,

and the guys in front of him would watch his eyes to see if he understood

English. If he flinched or looked startled, you knew he

understood English. Most of the older guards did not.

We had one guard who read the morning roll call. He was not

too bright. He would call off, “Bradley, James.

. . Rosie, George, ” and so on down the line.

After about a week of this, instead of answering “Here” or “Present”

someone began answering, “Here, you dumb shit” or “Here,

Pisshead” or “Here, you stupid S. O. B. ” We would

stand there roaring with laughter while the poor guard would stand there

scratching his head trying to figure out why we were laughing,

which, of course, he never did.

Stalag 3-A was about twenty-five miles south of Berlin. For

the last thirty days or so before we were liberated, around noon

each day hundreds and hundreds of American bombers flying very high would

turn just as they passed the camp and head for Berlin. A short

time later we could hear the sounds of exploding bombs. The

guards would point up to the sky and say, “Luftwaffe,

Luftwaffe. ” Our response was, “Your ass, ” We could hear artillery in the distance, but we also heard that Roosevelt had died. That news certainly did not make any of us fee] very good. On April 23 somebody in our tent was up early, probably to check on the water tap. When he went out he discovered there were no guards, not even on the main gate. He came back to the tent hollering. Everybody ran out to look around. About 9:00 A. M. a Russian Sherman tank outfit came driving in. The tanks knocked the main gate down and then flattened the barbed-wire fences. One of the tank commanders was a big husky woman, I’d say about thirty-five years old. At one point she jumped off the tank and ran over to one of the little, half-starved Russian prisoners, picked him up and hugged him. We later heard he was her brother who she thought had been killed. There were also female soldiers carrying rifles and Tommy guns. The Russians in the POW camp were given rifles and put back in the army. They were half starved but nevertheless they were back fighting. I’ve often thought that I would have hated like hell to have been any Kraut that got in their way as they marched on to Berlin. DIARY OF A KRIEGIE Edward IV. Beattie, Jr.

Edward Beattie of tile United Press is the only top. flight correspondent who saw from the inside Germany’s final crack. up. In September, 1944, the Nazis nabbed him at Chaumont-sur-Marne, and he was sent to Limburg, to Berlin, and finally to Luckenwalde.

Stalag 111-A, Luckenwalde APRIL 2

TODAY I am going to try to describe this incredible camp of 17, 000 men of

all nations which sprouted from the bleak Jueterbog Heath as a by-product

of German chaos. Words cannot describe it—words, for

instance, could never render the smells of Luckenwalde, a

compound of latrine, rotten cabbage, dirty bodies and

decay—but the part which can be put into words is bad enough. I

could have done a better job if I had continued in a new diary, day by

day, after the original was confiscated in Berlin January 25.

I didn't,

partly because the confiscation discouraged me, and partly because

for the first six weeks here at Luckenwalde, conditions were so bad

that nobody had the energy for much beyond the mechanics of eating and

sleeping.

I

never expected to see my original diary again. That I did,

can be thanked, I imagine, to the disbandment of Stalag III-D

a few days after my transfer. The III-D authorities, who

had promised to send on the book after censoring it, did so without

censorship. The Ill-A authorities assumed it had already been

read, and I succeeded in persuading a friendly German who told me it

had arrived, to give it to me before anyone here had had time to

leaf through it again.

The words will never do justice to Luckenwalde. But they will

give a bare outline for future reference, and that will be enough

for me or anyone else who has spent this winter here. Nobody

who was not

here could ever fully appreciate what Luckenwalde was like, anyway.

There are Russians, Frenchmen, Poles, Norwegians, Serbs, Italians. Greeks, Rumanians, Americans and men from all parts of the British Empire existing here, hungry, ragged, dirty, lice-infested and sick. Over half of them are here thanks to the fact that the Nazis are constitution. all)’ incapable of releasing their grip on anything they hold.

It

was this

trait which kept the armies at Stalingrad and Alamein when every

professional soldier knew it invited disaster, and which caused

Hitler to order the defense of France out at the coast, when he

might have been able to hold on a short line farther inland.

And this trait dictated that in the bitter cold of January, when the

Russians were pouring through the breaches in the Polish front,

these thousands of men should be uprooted from their permanent camps and

herded across the wind-whipped plains of eastern Germany to be dumped into

the limbo of Luckenwalde.

They were marched by day over the bitter

refugee roads in the great army of the homeless which swept westward

looking for safety in the crumbling Reich. By night they were

herded into barns and haystacks for a few hours of frozen sleep.

At the best, when they were on the point of collapse, they

were jammed into unheated boxcars or flatcars without covers and cast

adrift on the battered German railroads. Seldom were they

given food: they lived on what they could trade from the country people

with their Red Cross coffee, soap, chocolate and cigarettes.

There was no

rational reason for moving the tens of thousands of prisoners out of the

east to the dozen or two camps where the survivors have been penned up

ever since. In their old camps, they would have been

overrun by the Russians and in due course shipped back home to recuperate.

In their new camps, they are just so many more mouths to feed,

and even the starvation diet which the Germans grudgingly give their

prisoners in this year of grace is a strain on a between nation.

But Hitler and Himmler, who now is in charge of prisoners,

decreed that they be held, perhaps as hostages in one final

desperate bid for a deal. And camps like Luckenwalde,

where a few thousand French and Russians had been “living” in barracks

which are giant hovels, suddenly became great, bloated bedlams

in which many thousands were left to exist as best they could. Stalag Ill-A at Luckenwalde, a market town thirty-five miles south of Berlin, had a bad name as a punishment camp even before the influx from the east. A little German-French phrase book issued to camp. guards all over Germany to enable them to order prisoners around contains the sentence, “If you don’t behave, I’ll have you sent to Luckenwalde. ” French and Russian old-timers here say that anything up to i 5, 000 Russians have died in this camp, a great number from a typhus or plague epidemic two years ago but at least as many more from sheer hunger and neglect.

That was Luckenwalde before the new thousands were marched in, ......... (Can't read)....... But with one single exception, nobody connected with the running of this camp has made the slightest attempt to get the bed rod. essentials, food, fuel, straw and bedding, to provide a subsistence minimum for the inmates.

Of

the more than 4, 000 American enlisted men in camp, 2, 800 have been

sleeping since the beginning of February in seven big tents of sideshow

dimensions. Under them they have a little eternally damp.

straw. For cover they have two miserable, small-size

blankets apiece. They have one big open latrine and one water

point which must serve for washing and cooking for the entire bunch.

Each man rates a floor space about six feet long by two feet wide.

This, with the mud outside the tents, is all he has in which

to live out his existence. The tents are alive with bugs,

and since the Germans have not chosen to permit anyone to bathe since

arrival, there is no way to get rid of them. After

considerable argument by the senior American officer, one doctor was

permitted to visit the tent camp each day . . .

to “treat” the sick and wounded. He has almost no drugs or

equipment, and when he recommends transfer of the particularly

ill—the German definition is “in danger of death”—to the overcrowded camp

hospital, it usually takes days to get the Germans to act. The officers, and the G.I.'s of other nationalities, are luckier. They sleep 175 to a room in barracks which measure about 100 by forty feet, dank, dark and filthy. Like the men in the tent camp, they are full of lice, and their three-tiered wooden bunks are alive with bed-bugs and fleas. There is a stool for every two men, on the average, and a table for every thirty. This, plus the fact that animal heat has kept the barracks above freezing all winter, makes them sheer luxury compared with the tents.

Early in March, by some miracle which nobody can explain, enough Red Cross packages arrived to make possible the issuance of ~ne per man per week ever since. The Germans will ‘permit the Poles and French and Norwegians only one every two weeks, but the Norwegians, at least, get their own special packages from Denmark. The Russians get nothing at all, and aside from a few individuals who do clean-up |

| Page last revised 10/07/2014 |

|

|

Page last revised

10/07/2014

Page last revised

10/07/2014