|

This account of my

experiences in World War II is dedicated to my nine-year old twin

granddaughters. One day they may read this account and better understand

the horrors of war and the part their grandfather played in World War II.

|

|

| Kyra L. Jones |

Isla F. Jones |

Lawrence, Kansas

June, 2003

L. Martin Jones

Three Years at the University of Kansas

I was seventeen years old when I graduated from Osage City, Kansas,

High School in May of 1940 and enrolled at the University of Kansas (KU)

in September. The war in Europe had been raging for a year, since German

armies invaded Poland on September 1, 1939. There was much sentiment

against going to war in Europe, and President Franklin D. Roosevelt had

said he would never send American boys to fight on foreign soil.

Nevertheless, my parents and I anticipated we would ultimately get

involved in the conflict; therefore, I enrolled in the Reserve Officer

Training Corps (ROTC) at KU. Hoping to avoid serving in the army infantry,

I chose to enroll in the Anti-Aircraft Artillery

(M)

division of the Coast Artillery.

My ROTC class of fourteen men received excellent instruction in AA from

Captain Baker for three years. At the beginning of our third year, we were

given an ultimatum: either enlist, in which case we would be allowed to

finish our junior year of college

before being called to active duty, or be drafted immediately. My

classmates and I

enlisted on October 9, 1942, when I was nineteen.

Basic Training in Anti-Aircraft

Artillery at Camp Wallace. Texas

At the end of our junior year of college in May of 1943, when I was

twenty, the fourteen men in my ROTC class were called to active duty. We

were processed through Ft. Leavenworth, Kansas, where our group scored so

high on army exams, we were accused of cheating. We were sent by train to

Camp Wallace, Texas, for basic training in Anti-Aircraft Artillery.

Camp Wallace was located between Galveston and Houston and constructed on

a base of

seashells that had been dredged from

Galveston Bay.

The summer was so

hot and humid we did most of our hiking

at night. We traveled by truck to the northern tip of Galveston Island to

practice firing our 90-mm AA guns at sleeves (targets)

pulled on cables trailing behind airplanes from nearby Ellington Field.

One day our

gunfire cut a cable a few feet behind an airplane, and the

Air Force refused to pull

targets for several days. After we dug in our guns on the sand beach of

the

island, we had difficulty keeping them from sinking into the very wet

sand.

One day while I was on guard duty at Camp Wallace, a devastating hurricane

struck the Texas

coast at Galveston and

roared inland past Houston. I had great difficulty

walking against the 130-mile an hour winds, which were full of sand and

debris. Because the camp was only a few inches above sea level, the

buildings had been constructed on pilings about fifteen inches above the

ground. After the violent storm dumped several inches of rain in a few hours, the camp was flooded

with seven or eight inches of water, but the buildings were above the

water.

1

We trainees were three miles from camp on our 25-mile

overnight hike when the camp commander approached in his jeep and asked

where our gas masks were. Our orders were to carry gas masks, but our

battalion commander had directed us to leave them in camp. The camp

commander directed us to go back to camp, get our gas masks, and begin our

hike again. Our 25-mile hike was 31 miles long.

Awaiting Vacancies at Anti-Aircraft (AA) Officer Candidate School

After completing basic training I was sent with our group to Grinnell

College in Iowa to await reassignment. In October we were sent to KU to

await vacancies at AA Officer Candidate School in North Carolina.

For about three months at KU our group of fourteen men lived in the former

Sigma Chi fraternity house on Tennessee Street and ate our meals in

newly-completed Lindley Hall on campus. The fraternity, like most men's

living places, had closed temporarily because there were not enough men at

KU to justify keeping it open. When completed, Lindley Hall was first used

by the army and navy training units on campus.

We enrolled at KU after the fall semester started, and we were pulled out

of school in mid January before the semester ended. We received partial

credit for the courses in which we were enrolled. While on campus in the

fall of 1943 we were veteran college students at a university where we

knew our ways around. We thought we were BMOC (big men on campus).

Infantry Officer Candidate School at Fort Benning. Georgia

In mid January of 1944 I was promoted to Corporal and sent with our group

of KU men to Fort Benning, Georgia, to Infantry Officer Candidate School

(OCS). My hopes to avoid serving in the army infantry were shattered.

Because my training to this time had been in Anti-Aircraft Artillery, when

I arrived at Ft. Benning I had not seen a Browning Automatic Rifle or a

mortar, two basic weapons of the infantry. Immediately after arriving at

Ft. Benning, I visited on two occasions with my younger brother, Harold,

who had completed basic training there and was being transferred.

The instruction and training I received at Ft. Benning were excellent.

Instructors were knowledgeable and outstanding speakers. Some

demonstrations and combat problems in which we engaged were impressive. My

Tactical Officer, Lt. Huntsman, once told me to go into the woods at night

and practice giving commands, as I had to become more vocal and aggressive

in giving them. When I went into the woods to practice, I joined other

officer candidates who were barking commands in the total darkness. I

barely qualified as a marksman with the Garand M-1 rifle, but I scored

high on a course where we ran along and shot from the hip as targets

appeared unexpectedly along the course. I received high marks for a combat

exercise in which I played the part of an infantry company commander.

2

After five months of training in the infantry, including leadership and

tactics, we were commissioned Second Lieutenants on June 20, 1944, and

assigned to various infantry units. Our group of men from the ROTC program

at KU completed basic training and Infantry Officer Candidate School

together. The general who spoke at our graduation and commissioning

ceremony, impressing us with how serious our army jobs would be, said, 'In

six months you will be overseas and in combat." In six months, with one

day to spare, I was overseas, in combat, and a prisoner of war.

My Service With The 106th Infantry Division

After a brief visit at home in Osage City, I joined the 423rd

Regiment of the 106th Infantry Division at Camp Atterbury, Indiana. I was

twenty-one years old and a brand new Second Lieutenant. I was an infantry

platoon leader in Company G, Second Battalion, where my platoon sergeant,

John Parchinsky, had completed sixteen years of military service. When I

joined the 106th Infantry Division, I had the least amount of

infantry training of the forty men in my platoon, yet I was their leader.

The division, which had completed Tennessee maneuvers while I was at Fort

Benning, had been declared "combat ready." Of the six commissioned

officers in Company G, two reported to the division at

Camp Atterbury

after I did.

In August the division suffered a severe blow. Most of the well-trained

men who had been on maneuvers were shipped overseas as replacements in

various infantry units. The five excellent sergeants, non-commissioned

officers, in my platoon remained, but some 30-32 well-trained men were

gone. From late August to late September we received replacements, most of

whom had no training in the infantry. Many came from colleges where they

had been in Advanced Student Training Programs. Suddenly I became one of

the men with the most infantry training in my platoon. The sergeants in my

platoon, Lee Darby, John Parchinsky, Jesse Bishop, Ivon York, and Billy

Moore, were the strength of our platoon, and I depended on them, probably

more than I should have, but they were the only ones with any significant

amount of infantry training.

With very young, inadequately-trained men whom I hardly knew, we left

Camp

Atterbury on October 9 and traveled by train to Camp Miles Standish near

Boston. On October 13 I made a visit to Boston. Another train ride on

October 16 took us to New York City. We boarded the Queen Elizabeth at

Pier 88 in the Hudson River shortly after midnight on October 17 and

sailed from New York City at 7:00 am, passing Ellis Island and the Statue

of Liberty as we sailed through the harbor to the Atlantic Ocean.

The Queen Elizabeth had been camouflaged by painting the exterior several

shades of gray and white, but the interior was beautiful, as the ship was

constructed as a luxury cruise liner. Like the other officers, I ate meals

in the captain's large dining room. Almost 16,000 soldiers were on board

for this voyage. Half the men were below decks and half on the several

exterior decks for twelve hours. Then a

3

complicated shift was made as the men traded places for the next twelve

hours. The men below decks ate two meals during the twelve-hour period.

Because the Queen Elizabeth was one of the fastest ships afloat, capable of doing 24 knots, we sailed a zigzag

course without escort. To my knowledge we did

not see another ship during the five-day crossing. My first ocean voyage

was uneventful.

On October 22 we sailed into the Firth of Clyde and docked at Greenock,

several miles west of Glasgow, Scotland. On October 24 we disembarked and

boarded a train at Greenock. About 3:00 am on October 25 we arrived at

Toddington Station in the Cotswolds (Sheep Hills) ten miles northeast of Cheltenham, England, where we bivouacked on the vast

grounds of Toddington Manor until December 1.

While at Toddington Manor we conducted some training, did some hiking,

fired our rifles once at a range, and I taught classes. I received a four-day pass and went to London where I

visited St. Paul's Cathedral, Madame Tussaud's Wax Museum, Westminster Abbey, the Tower of London, Piccadilly Circus,

and Trafalgar Square. I saw Buckingham Palace, Houses of Parliament, Tower

Bridge, and other sights.

When I returned to camp from a training exercise on November 28, I was

surprised to receive a message at company headquarters to call my older

brother, Warren, who was in Cheltenham. His artillery outfit, attached to the 75th Infantry Division, had just

arrived in England. On his way to the port where the division's equipment

had arrived, he called the Red Cross to learn where I was stationed. He

took a train to Cheltenham and called me. I checked out a Jeep from our

motor pool and drove to Cheltenham where Warren was waiting in a pub. He

accompanied me back to camp and stayed overnight. We had a wonderful

visit, just as Harold and I had at Fort

Benning ten months earlier. Warren had to leave the next morning.

On December 1 my outfit traveled by train from Toddinton Station to Southhampton and

boarded a ship. On December 2, my 22 birthday, we crossed the English

Channel and dropped anchor in the harbor at LeHavre, France. The next day

we boarded landing craft and went ashore, marched inland nine miles in the

rain, and pitched our tents in a muddy field

at Camp J-56. Rain fell most of the five days we were in this cold and

muddy camp.

On December 8 we moved by truck through Amiens, Cambrai, and Valenciennes,

France, and into Belgium. The next day, as much snow fell, we continued

the trip through Dinant and Marche to some woods near St. Vith, Belgium.

We had to clear six inches of snow before we could pitch our tents on frozen ground. After I assigned areas to my

sergeant squad leaders, I pitched my tent and returned to see how my men

were doing. I found four sergeants somehow huddled in one tent with a

bottle of brandy they had liberated." This was my introduction to the term

liberated," a word I found useful on many occasions later. Possibly to

keep me from reprimanding them, they offered me a taste of the brandy. I

took a swig and returned to my tent for the cold night. St. Vith, an

important crossroads town, was

4

our division headquarters. Located in the Ardennes Forest, it was about

ten miles behind the front lines, which ran along the German-Belgium

border.

On December 10 the 106th Infantry Division, favored by snow and

a low ceiling, moved to the front and relieved the 2nd Infantry

Division, taking over their positions foxhole by foxhole. The 2nd

Battalion of the 423rd Infantry, including Company G, was

assigned to division reserve in Born and Medell, Belgium. Like the 28th

American Infantry Division to the south of us, the 106th

Division had approximately twenty-three miles of front to defend, almost

five times the amount an infantry division should be expected to defend.

For this reason the division had only one battalion, instead of the

recommended three, in reserve.

My platoon was assigned to Born, Belgium, a village four miles north of

St. Vith. My squad leaders and I assigned our men to homes in the village.

The company mess hall and a make-shift shower facility were set up in a

schoolhouse. A fellow company officer, Lt. Earl W. Browne, and I occupied

a cold, unheated bedroom on the second floor of the Theissen home.

However, we kept warm at night under several layers of blankets. Browne

and I had access to a comfortable sitting room on the first floor of the

Theissen home, but we did not have much time to use it. On several

occasions, however, we used it to visit with twenty-six year old Johanna,

who spoke no English. Johanna, her mother, and her brother occupied the

home. I did not see another brother, who was AWOL from the German army and

hiding in the woods earlier in the war. The family had operated a sawmill

in the lower level of the home by diverting water from a nearby stream to

provide power. They had turned the sawmill over to a platoon of U.S.

engineers to prepare and stockpile timbers for future bridge-building

activities when the Allied advance resumed.

From December 11 through December 15 we heard much talk about an impending

attack from the German army. But American intelligence assured us there

would be no attack because, they emphasized, the German army was incapable

of mounting a serious attack. American intelligence officers in Paris

refused to accept several reports that the Germans were amassing thousands

of men and hundreds of tanks opposite our positions. These officers

attributed the reports to exaggerations of "inexperienced troops.' On

December 15 I took a shower and put on a new pair of combat boots. Though

I did not know it, I ate the last good meal I would have for about six

months. I slept soundly under several blankets.

The Battle of the Bulge. Please refer to maps on pages 8 and 9.

Following the June 6, 1944, invasion of France, after Allied troops broke

out of Normandy and advanced across France and Belgium, Allied supply

lines stretched longer and longer. In September frontline troops could no

longer be supplied adequately by trucks of the "Red Ball Express' speeding

from French ports to the front lines, and the advance came to a halt.

Heavy fighting took place in several areas, but the front lines remained

substantially unchanged until mid December.

5

At Hitler's direction Germany planned an attack along the German border

with Luxembourg and Belgium and an advance to the North Sea to cut off

British troops in Holland from their source of supplies, hoping this would

divide the Allies and force them to surrender. Germany quietly amassed

armored divisions and infantry divisions in preparation for attacking the

weak point along the Allied defense line.

Top Allied generals, including Supreme Commander Eisenhower, made numerous

mistakes which made possible the initial success of the German attack. The

largest blunder was holding the strong conviction that Germany did not

have enough men, tanks, and gasoline to mount a major attack. In the fall

Eisenhower had made a bet the war would be over before Christmas.

Eisenhower and his staff believed that even if Germany launched an attack,

it would not come in the Ardennes area of

Belgium because, the generals insisted, there were no major objectives in

the area. But they forgot their history lessons. In both World War I and

May, 1940, in World War II Germany's invading forces made their initial

attacks in the Ardennes.

This egregious miscalculation of German strength and potential led U.S.

generals to make other mistakes. The 28th Division had suffered

heavy casualties in fierce fighting in the Hurtgen Forest in November, and

men of the 106th Division were inadequately trained and

experiencing our first combat. Consequently, the Ardennes front was

defended by a badly-weakened division and a division with no combat

experience. The two divisions were spread too thin along almost fifty

miles of the front. In addition, all reserves were removed from behind the

frontline troops, leaving only the pitifully thin line of defense

stretched along the German border.

Allied intelligence officers ignored several reports, from both civilians

and frontline soldiers, that Germany was amassing hundreds of tanks and

thousands of men opposite the 28th and 106th

Infantry positions in the Ardennes area. Furthermore, Allied intelligence

had lost track of a

German armored division, believing the division was near Berlin, when, in

fact, it was part of the 420,000 men and 1,200 tanks poised to attack the

front held by approximately 65,000 American infantrymen who had little

tank support. Because the Allied Air Force was grounded in England by bad

weather, the overwhelmed infantrymen had no air support in the first

crucial week of the battle. For some unexplained reason, men of the 106th

Infantry Division had not been issued winter clothing.

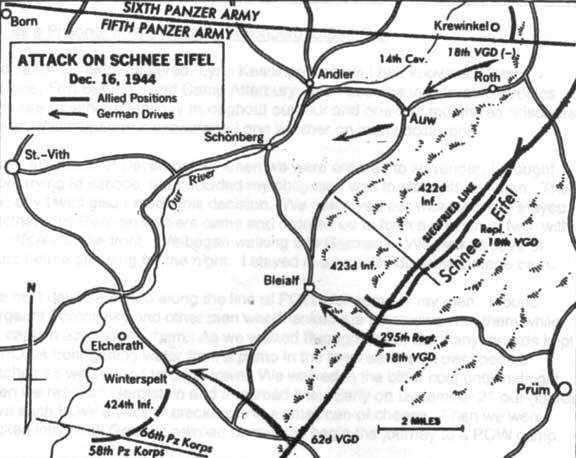

The German attack, began with a forty-five minute artillery barrage at

5:30 in the morning of December 16. Several hours later when frontline

troops reported German advances at several points, Allied generals, still

convinced that Germany did not have enough strength to make a major

attack, and believing that no attack would come in the Ardennes Forest in

any case, described the attack as a "mere skirmish," and they took no

immediate action. Not until the second day of the battle, after the 422nd

and 423rd regiments of the 106th Division had been

surrounded while holding their positions, as ordered, did Allied generals

commit more troops to the battle in an attempt to slow the German advance.

But this was too late for men of

6

the two beleaguered regiments on the Schnee Eifel (Snowy Mountains).

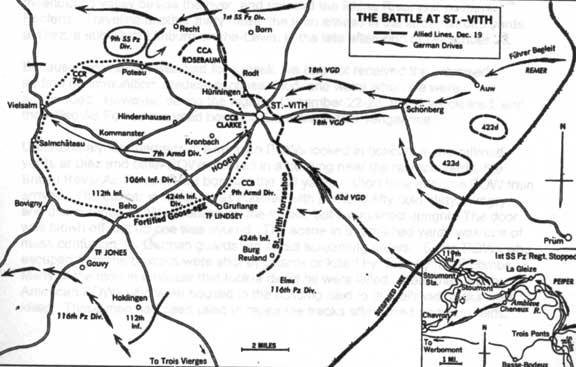

On December 16, the first day of the battle, we went by truck through St.

Vith and Schonberg to near Andler. That evening Captain Murray ordered me

to take my platoon across the ice-cold Our River and try to make contact

with an outpost of the 14th Cavalry Division. I led my men

across the waist-deep stream, made contact with a squad of 14th

Cavalry Division men, and began to dig in, as ordered. In the middle of

the night I received orders to recross the Our River and rejoin the

battalion which was moving to near Auw in an attempt to help stem the tide

of German tanks and men moving rapidly west toward the road junction at

Schonberg.

At daybreak on December 17 a German artillery barrage destroyed our

ammunition truck, the only two American tanks I saw during the battle, and

several of our bazookas (antitank weapons). The junction of German forces

at Schonberg before noon on December 17 had surrounded the 422nd

and 423rd Regiments of the 106th Division and cut

off our escape route. On December 18 the 2nd Battalion rejoined the

regiment near Radscheid and fought an unsuccessful battle trying to stem

the tide of German forces moving north on the Bleialf-Schonberg road.

Early in the battle the commanders of the two regiments were told to hold

their positions at all costs, and they were told that ammunition, medical

supplies, food, and water would be supplied by air. However, because of

bad weather, the Air Force was grounded in England and the promised supply

drops were not made.

On December 18, after many of the soldiers of the two regiments had

exhausted the meager supply of ammunition they had carried into battle,

the commanders of the surrounded regiments received the following orders:

"Attack Schonberg, do maximum damage to enemy there; then attack toward

St. Vith. This mission is of gravest importance to the nation. Good

luck."

The regimental commanders were told the U.S. 7th Armored

Division would move through St. Vith and meet us at Schonberg. However,

German control of the roads around Schonberg was so complete that neither

the infantry regiments nor the 7th Armored Division reached the

rendezvous.

The December 18 order required the surrounded soldiers, most of whom had

no ammunition, to attack back to the northwest toward Schonberg. However,

without ammunition, we could attack nothing. We tried to sneak out of

entrapment under cover of darkness during the night of December 18-19. We

crossed the Ihrenbruck stream and reached a point just east of Hill 504.

We were almost in sight of Schonberg when daylight came and a heavy German

artillery barrage inflicted more casualties and halted our attempt to

reach this road junction. Throughout the day of December 19 we were the

target of several German artillery and mortar barrages.

At mid afternoon of December 19 the two regimental commanders discussed

the

7

crisis. After failing to reach Schonberg, suffering some

casualties, and being reluctant to suffer more casualties in a hopeless

cause, they ordered the surrender of the soldiers who remained.

Colonel Cavender of the 423rd Regiment said, in effect, "We

have ceased to be an effective fighting unit. Most of our men have no

ammunition, and I cannot sacrifice more men in a hopeless cause. We will

surrender at 4:00. Order your men to destroy their weapons and remain in

place." Almost 7,000 men of the 106th Division became prisoners

of war on that fateful day.

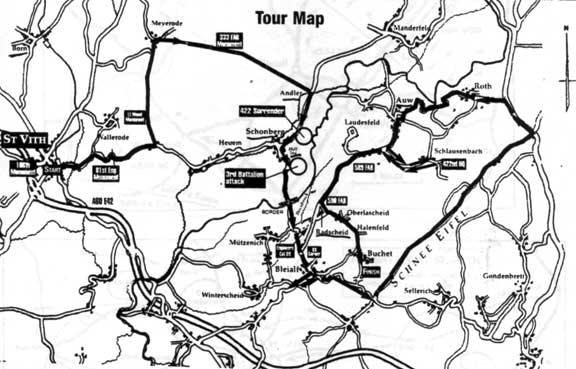

Note the location of Born (upper left), St. Vith (left

center), Schonberg (center), Andler (north of Schonberg), Auw (east of

Andler), Radscheid (southwest of Auw ), Bleialf (south of Radscheid), and

Hill 504 (south of Schonberg). Auw, Radscheid, and Bleialf are in Germany.

8

9

Life as a Prisoner of War (POW). Schonberg to Bad Orb

Soon after we were captured, Lynn Kessinger, whom I had known at Camp

Wallace, Fort Benning, and Camp Atterbury, and I become inseparable

buddies. We were together every day throughout our four and one-half

months as prisoners of war. We helped and encouraged one another on many

occasions.

In late afternoon of December 19 when we were ordered to surrender, I

thought about trying to escape, but I decided my obligation was to stay

with my men. The next day I was glad I made this decision. We destroyed

our weapons and stayed together until German soldiers came and ordered us

to form a column of two, with the officers at the front. We began walking

into Germany. We walked several hours before stopping for the night. I

stayed in a partially-destroyed stone barn.

The next day I searched along the line of POWs for some of my men. I found

Sergeant Parchinsky and other men who thanked me for staying with them

while the captain abandoned them. As we walked through Prum, Germany,

guards kept us POWs from getting water from a pump in the town square.

Townspeople watched as we trudged through town. We walked in the bitter

cold until midnight when we reached Gerolstein and a railroad line. Early

on December 21 our guards gave each POW a sack of crackers and a small can

of cheese. Then we were packed into small German railroad boxcars to begin

the journey to a POW camp.

We were locked in the boxcars without food or water for four days and

nights in extremely cold weather. The train moved east to the Moselle

River, down the meandering valley beside the river, and crossed the Rhine

River just south of Koblenz. Traveling another thirty miles, the train

arrived in the large railroad yards at Diez, a suburb of

Limburg-on-the-Lawn, in the late afternoon of December 23.

Because the weather was bad for a week, we had not received the promised

airdrop of ammunition, medical supplies, food, and water when we were

surrounded. However, during the night of December 22-23, the skies

cleared, and the Allied Air Forces resumed bombing Germany with a

vengeance.

Unfortunately for hundreds of American POWs locked in boxcars in the

railroad yards at Diez and other POWs housed in a building near the

railroad yards, the British Royal Air Force (RAF) bombed the rail yards a

short time after the POW train arrived. The boxcar in which I was huddled

with perhaps fifty cold, dirty, hungry, and discouraged POWs bounced on

the tracks, but it remained upright. The door was blown off, but no one

was injured. The scene in the railroad yards was one of mass confusion, as

German guards ran about screaming orders. Some POWs who escaped from the

boxcars were shot by guards or killed by "friendly" RAF bombs. Many of the

men in a boxcar that took a direct hit were killed. More than eighty

American POWs who were housed in the building next to the railroad tracks

were killed. These men had been used to repair the tracks after Allied

bombing raids.

10

During this air raid, while locked in a boxcar and exposed

to the falling bombs,

I suffered the most helpless feeling I experienced during my time as a

POW.

An RAF after-the-battle report states that fifty-two

Lancaster bombers took part in the Diez raid and dropped, among other

bombs, twenty-five 2 1/2-ton bombs. A German newspaper dated Christmas Day

reported that 142 German civilians were killed and 161 German homes were

destroyed in this December 23 air raid.

Our POW train remained in the Diez railroad yards on December 24 while

work

crews repaired two tracks, one for east-bound traffic and one for

west-bound traffic.

On Christmas morning our guards allowed us to leave the boxcars to relieve

ourselves while German people watched from a distance of twenty-five

yards. This was the first time we were out of the filthy boxcars in four

days. As we were being packed again in boxcars, we received one British

Red Cross food box for each group of six POWs. My group drew straws to

determine the order in which we would select items from the box, which

contained powdered milk, a small piece of cheese, a tin of canned meat, a

small pack of cigarettes, a hard chocolate bar, a box of hard biscuits, a

can of cocoa, and more.

Life as a Prisoner of War at Stalag IX-B, Bad Orb

On Christmas Day we were again locked in the boxcars, this time for three

days and nights, arriving in Bad Orb, Germany, on December 28. We walked

from the railroad station to Stalag IX-B, a badly overcrowded camp with no

conveniences. The Germans were unprepared to care for the thousands of men

in this camp. I was in an unheated room with dozens of men. There was only

one toilet in the

room and, because it did not operate properly, the floor around it was

flooded most

of the time. We had to assemble outside each day for the guards to conduct

a count of POWs. Unfortunately, they could never get the count right, so

we POWs stood outside in bitter cold for hours while the guards took turns

counting.

My feet were badly frostbitten by the time I reached Bad Orb. The problem

undoubtedly started on December 16 when I waded across the ice-cold Our

River twice and had no opportunity to dry or warm my feet. Medical doctors

(POWs) told me to keep my feet as warm as possible. I sat cross-legged on

my wooden bunk trying to get my feet warm.

We had to take our steel helmets to a central kitchen to

get our daily food ration,

which usually consisted of a slice of bread, about the size of two normal

slices of

bread, and a small bowl of "green homer soup. We POWs called the soup "green homer because it was a dark green color and it raced through our

digestive systems in a short time. The very thin soup was made of

dehydrated vegetables that had gotten wormy. At first we were a little

concerned about the small white worms in the soup, but later we hardly

noticed them, commenting that we were

11

getting some protein in our diet. According to an official German Food

Ministry directive, the black bread, which was heavy and coarse, was made

of 50% bruised (pulverized) rye grain, 20% sliced sugar beets, 20% tree

flour (sawdust), and 10% minced leaves and straw. On several occasions

Kessinger took my helmet and obtained my food ration for me, while I tried

unsuccessfully to get my feet warm.

Life as a Prisoner of War at Oflag XIII-B, Hammelburq

On January 10, after thirteen cold, miserable days at Bad Orb, the

commissioned officers were packed in boxcars again for an overnight train

ride to Hammelburg, Germany. As we walked several miles from the railroad

station up a long hill, I felt as if I were walking on stilts, as I had no

feeling in my feet. Even when I stomped on one foot with the other, I felt

nothing. I was concerned about my frostbitten feet and the possibility

they might have to be amputated if gangrene set in. Just beyond the crest

of the hill, we entered Oflag XIII-B (Offizier Lager, Officer Camp) in

which some 4,300 Serbs and Yugoslays had been imprisoned for more than

four years. I was in the first group of American POWs to arrive at this

camp on January 11.

Conditions at Oflag XIII-B were somewhat better than at Bad Orb. I was in

a room with fifty men. We had double-deck wooden bunk beds with very thin

straw mattresses and one-half a blanket for each man. Our daily food

ration was the same as we had at Bad Orb, except that the soup

occasionally had potato peelings and marble-sized potatoes in it, and two

or three times we had a thick barley soup. Our black bread came from

Wurzburg, some twenty-five miles to the southeast. Many days we had no

bread because, our guards told us, "Nichts brot; Wurzburg boom, boom," to

inform us that Wurzburg and the bakery had been bombed by Allied airmen.

Because the ersatz (substitute) coffee we received was hot, or could be

heated, we frequently used it for shaving.

We had to walk about two blocks to our latrine, but we could not go to the

latrine while an air raid alert was in effect. We had a small metal stove

in the middle of the room, and we received 7-8 small charcoal brickettes

each day to provide heat. We debated whether it was better to burn all

brickettes at one time, in which case the stove got warm for a few

minutes, or bum them one at a time, in which case the stove never put out

any heat, as what little heat the stove generated was absorbed by the

stove itself. Because Kessinger was able to coax more heat from the stove

than others, he was assigned to manage our stove as he saw fit.

We POWs had several major concerns. Fear of being shot by guards was a

constant worry. On January 21 Lt. George Varium (Vaream) was killed by a

guard during an air raid alert. On March 21, as Lt. Charles L. Weeks was

returning to our barracks from the latrine, I saw a guard shoot him in the

back and kill him, apparently because Weeks was not moving fast enough to

get inside our room when the air raid siren sounded. We POWs protested to

the camp commandant,

12

but nothing was done about these killings. Every few days the Serbs on the

burial detail told us they had buried one of the American POWs who had

died from injuries, illness or possibly starvation.

Losing our freedom to come and go as we pleased was a terrible shock to

us. We could go outdoors only when guards told us we could go, and we had

to return to our barracks when they told us to return. We ate our meager

daily ration of soup, bread, and coffee when it was brought to our

barracks. Under threat of being shot, we lined up outdoors to be counted

whenever we were told to do so, which was not often at Oflag XIII-B. We

were forbidden to visit the compound in which the Serbs and Yugoslays were

imprisoned, though we occasionally cut the barbed wire fences separating

the compounds and sneaked into their compound under cover of darkness. It

is true that until a person has his freedoms taken from him, he does not

truly value the many freedoms we normally take for granted.

Boredom was another problem. POWs did various things to keep busy. Because

we were always hungry, food was by far the most popular topic of

discussion. Many men talked about nothing but their favorite foods, the

foods they wanted to eat for their first meals after getting back home,

and the best places to eat in different parts of the United States. New

Yorkers, for example, said Lindy's served the best cheesecake in the

country. Like many POWs, Kessinger made lists of the best places to eat in

different U.S. cities. I participated in a Bible study group conducted by

one of our POW chaplains and did some walking in the compound.

Most POWs lost 30-50 pounds and became very weak during the first two or

three months of captivity. Though some men worried about living until we

were liberated, I never worried much about this until later when an

incident occurred on March 27-28. Some men who were injured or sick

understandably worried about living until we were liberated, and, in fact,

some men died in prison camp of injuries or illness. The Serbs operated a

poorly-equipped and poorly-staffed hospital in the camp, but POWs who were

badly injured or became seriously ill frequently died.

While I was a POW I had no tub baths and only one shower. Once at

Hammelburg the German guards led us to a small room with one shower head

in the center of the room. They packed the room with naked POWs, turned on

the water one minute for us to get wet, turned off the water for one

minute as we soaped up, and turned on the water for a minute for us to

rinse. When we removed our clothing to shower, I was shocked that other

men were very thin. I realized that I looked the same as they did, with

bones protruding everywhere. In the room in which we removed our clothing

there was a scale graduated in British stones. I weighed 81A

stones, or approximately 120 pounds, down from the 155 pounds I weighed

when the Battle of the Bulge started. Most men lost more weight than I

did.

Having been bombed by the Royal Air Force while locked in a boxcar at Diez

(Limburg) on December 23, we feared the Allied air forces might again bomb

us by

13

mistake in the prison camp. We always feared that we might be caught in

no-man's-land when the Allied armies reached us and liberated us. We

learned that Hitler had given an order late in the war to kill all POWs

rather than let them be liberated, but the order was not carried out.

When we arrived at Hammelburg on January 11, the weather was very cold, so

I spent most of the time in my barracks trying to keep my feet warm. As

temperatures moderated in March, I went outdoors for walks in the

compound, always making sure I ran back to my barracks, as ordered, when

the camp air raid siren sounded.

On two occasions a guard brought to our room one toothbrush for fifty men.

I was the lucky winner of the second toothbrush, which I used until I

returned to the United States. Perhaps this explains why I had fewer

problems with teeth after the war than many former POWs.

Shortly after we arrived at Hammelburg, Kessinger and I visited with Serb

and Yugoslav POWs across an open area of about ten yards between the two

barbed wire fences, with manned guard towers spaced along the fences. We

could not speak their language and they could not speak English, but we

managed to communicate. They were pleased to learn that Allied armies had

reached the western German border and that we thought the war would not

last much longer. Frequently we saw Allied planes in the sky above us. Two

Serbs with whom Kessinger and I visited invited us to their barracks for a

party. They had saved supplies from Red Cross food parcels and food

parcels they had received from home in earlier years. They said they would

make a cake for the party.

On the night of the party, Kessinger and I took a great risk and sneaked

through holes in both barbed wire fences. Our new friends met us and led

us to their barracks, which was filled with Serb and Yugoslav POWs. We ate

the cake, which was more like pudding than cake, but it tasted very good.

While we were partying, two German guards entered the room. Kessinger and

I knelt down back of a group of our new friends. One guard took several

steps forward as he looked carefully around the room. Then he turned and

walked out with his comrade. Two or three hours later Kessinger and I

sneaked back through the two fences and the open space between them to our

barracks.

U.S. prisoners slipped through the fences to the other compound quite

frequently. Many mornings our guards were angry because someone had cut

holes in their barbed wire fences. Our guards repaired the fences

frequently.

14

Liberation. Recapture and Walking Across Bavaria in the Spring Time

About 4:15 in the afternoon of March 27 we heard small arms fire and saw

red streaks left by tracer bullets outside our windows. A U.S. tank force

attacked Oflag XIII-B and drove off the guards. When the tanks came

through the barbed wire fences, we POWs shouted and jumped with joy

because we were liberated. We did not know that our freedom would last

only a few hours.

Task Force Baum, named for its commander, Captain Abraham Baum, had

fifty-four tanks, armored vehicles, and jeeps and about 300 men when it

left its assembly area south of Aschaffenburg at 10:30 pm on March 26. The

plan was to arrive at Hammelburg early the next morning and rescue some

300 American prisoners, including General Patton's son-in-law, Lt. Colonel

John K. Waters. The task force engaged in heavy fighting on the way to

Hammelburg. Furthermore, as the lead tanks started to cross a bridge over

the Saale River at Gemunden at 11:00 am on March 27, German troops blew up

the bridge, forcing the task force to detour to the north to find a bridge

over which the tanks could cross the river. The task force successfully

attacked a road block in Hammelburg and moved up the hill to the prison

camp. They drove

off the guards and rolled into the camp late in the afternoon,

some eleven hours later than planned. They had less than half their

vehicles and about 240 men when they liberated almost 1,400 American POWs.

Most of the 4,300 Serbs and Yugoslays stayed in their compound.

Kessinger and I were among some 900 men who followed the tankers for a

short distance out of the camp. Captain Baum stopped the procession and

announced that we were almost sixty miles from the U.S. frontline troops.

He said only a few of the POWs could continue with the tankers as they

tried to fight back to the American lines. He said the rest of us were on

our own. Many POWs, including most of the sick and injured, returned to

camp. These men were set free about April 10 when U.S. troops again

liberated the camp. A large group of men was recaptured, marched to the

railroad station, and shipped to a camp in Nurmberg.

The task force reorganized and prepared to move out at first light on

March 28. But by morning the Germans had encircled the task force with

Tiger tanks, 88mm anti-tank guns, and infantry. At daybreak when the task

force started to move, a fierce, but short, battle took place. Every

vehicle of the task force was destroyed. Except for three or four men who

sneaked some fifty miles to American lines, all U.S. soldiers were killed,

wounded, captured, or recaptured. Task force Baum was gone forever. Many

reports have been written about Task Force Baum and its unsuccessful

attempt to liberate American POWs at Hammelburg and return them to

American lines. Captain Baum wrote about the attack in a book titled

"Raid."

Kessinger and I tried to distance ourselves from the vicinity of the camp.

But we had not gone far when, about two or three o'clock in the morning of

March 28, we

15

were recaptured by German troops and forced to start

walking to the southeast, away from the camp and the nearest Allied lines.

After a short time there were about 160 recaptured POWs in our group. We

walked from about three o'clock in the morning until noon. After resting

for two hours, we walked until about six o'clock in the evening before

stopping for the night in a large barn. Because we were emaciated and very

weak, this first day's walk was extremely difficult. When I dropped onto

some hay in the barn, I thought I might not be able to get up again. I

thought this might be as far as I could go. This moment was the most

hopeless moment I experienced during my POW days. I prayed for strength to

keep going, knowing we might be liberated before long. I was weary and my

whole body ached, but I fell asleep quickly. Early in the morning of March

29 our guards awakened us and we started walking again. I was surprised

that I could get up and walk.

From March 28 to May 2 we walked almost every day, taking only a few days

off. As we walked across the German countryside, we found we could steal,

or "liberate," potatoes almost every day, and occasionally we could

liberate' large loaves of bread. Once in a while we could get sugar beets

from fields near the roads. German farmers grew these large beets to feed

cattle, but we found they provided some moisture which we needed badly. As

we walked each day, I got stronger physically, and my mental attitude

improved. After a few days I was making the daily springtime hikes with

less difficulty than I experienced at first.

Our guards led us across country, avoiding cities and possible encounters

with German SS troops, whom they disliked almost as much as we American

POWs disliked them. We walked narrow back roads with a file on either side

of the road. A team of horses pulled a wagon at the end of our column. The

guards put their packs on the wagon which they took turns riding.

Occasionally they let a sick or injured POW ride the wagon for several

hours.

I

kept a list of many of the villages through which we walked and in which

we stayed overnight. I wrote the names on paper and hid the paper with the

draw-strings around the waist of my field jacket. On March 30 we walked

through Herlheim. On April 1 our Easter Sunday services were interrupted

by U.S. P-47 fighter planes flying low overhead and strafing several

nearby villages. We carried white cloths which we placed on the ground to

form the letters "POW to tell the fighter pilots who we were. Our message

was received because two planes flew low overhead and "dipped" their wings

to tell us they received our message, and no planes strafed our group.

When I returned home in June, I learned that my college roommate, Bob

Coleman, who was a P-47 fighter pilot, was shot down and killed that

Easter Sunday very near the place where we POWs saw the planes. I wrote an

account, I Will Always Wonder," about this experience.

We stayed overnight near Oberlenbach on April 2, near Vach on April 3, and

in Furth, a suburb west of Nurmberg, on April 4.

16

On the morning

of April 5 we walked through the southwest suburbs of Nurmberg,

where work continued in badly-damaged buildings. We stopped to rest before

noon, just as U.S. airplanes started bombing the city. Huge columns of

black smoke rose to the sky, and we told our guards that Nurmberg would be

"caput" (destroyed). This was the last 1,000-plane air raid of the war.

As we watched the bombs fall, they started falling closer and closer to

our group of American POWs and a dozen German guards resting beside a

road. Then we lay flat on the ground as bombs fell upon us. While lying on

the ground, I turned my head a little from side to side, trying to

determine by the bombs' screaming sounds whether they would fall to one

side or the other of me. The ground shook violently as each bomb exploded,

and we were covered with dirt and debris. There was very little shouting

or crying out from the men.

When the bombing stopped, I brushed off dirt and determined that I was

uninjured. Most of the men near me, including Kessinger, were killed or

injured. The right side of Kessinger's head was a mass of flesh, blood,

and bone fragments. He took a swipe at his head with his hand and was

horrified, thinking he had been badly injured. I'll never forget the look

on his face. I cleaned Kessinger's head and found that he had a bad cut

above his right ear. Blood was flowing profusely, so I made a pad of cloth

for him to hold to his head. Several men near us were killed, and one man

lying next to us had both legs severed just above his knees. He was in

shock as he calmly smoked a cigarette for a few moments before he died.

Kessinger and I did what we could to help and comfort several

badly-injured men.

Approximately twenty-five POWs, a German guard, and the two horses that

pulled the guards' wagon were killed. Other POWs were injured, some badly.

One group of injured men, including Kessinger, walked to a nearby

hospital. A group of five POWs and a guard were assigned to bury the dead.

The remaining POWs, about one hundred men, continued walking the rest of

the day. During the night I was awakened by Kessinger, who, with other

walking wounded, rejoined our group. They received no help at the

hospital, so the men who could walk decided to catch up with our group,

bringing our number to about one hundred and fifteen.

On April 6 we walked to Feucht, southeast of Nurmberg. Some of the wounded

men were taken to a nearby hospital. We received one Red Cross food parcel

for every two men. Kessinger and I shared the contents of one box.

Most days we ate food we could liberate." On some days, our guards

provided a loaf of bread for eight men. Father Cavanaugh and Captain

Madden cut the bread and gave pieces to our group of eight men. Though our

diet consisted almost entirely of potatoes and bread, we ate more than we

were given in the POW camps.

Kessinger and I developed a plan that we followed at the end of our walk

each day. We managed to be near the front of our column when we stopped.

He searched

17

the farmyards for food, and, because I spoke a little German, I begged for

food from the German housewives. Infrequently they gave me potatoes or

bread. Kessinger and I would meet to share whatever food we had obtained

by hook or crook.

One evening Kessinger, a farmer from Illinois, returned with his helmet

full of something that could not be identified. When I asked him where he

got it, he said, "Let's eat it first, and then I'll tell you." After we

ate the mystery concoction, he told me that when the German housewife

slopped the hogs and returned to the house, he pushed the hogs aside and

scooped up a helmet full of the slop. The only things we could identify

were marble-size potatoes and potato peelings. But the slop filled our

stomachs and, we hoped, gave us some energy to keep going.

On April 9 we walked through Seligenporten. Our walking tour brought us to

Evasbach on April 10, Kevenhull on April 12, and Zell on Friday thel3th.

I

remember Zell because the tall, narrow church steeple appeared to be

covered with gold leaf. From Zell we walked along a narrow, one-lane road

to Schafshill.

After noon on April 17 we came to the Danube River opposite Weltenburg, a

small monastery town. We crossed the river on a raft-like ferry. The

current moved the raft from one bank to the other, depending on how the

operator set his large rudder. The raft did not float downstream because

it was linked by a cable to a triangular-shaped piece of metal with two

pulley wheels attached. This metal piece moved on the pulley wheels back

and forth on a stationary cable which was anchored to the mountainside on

the east bank of the river and to a high tower on the west bank.

We enjoyed a slow, smooth, peaceful crossing of the Danube River and

stayed near Weltenburg that night.

We visited Helchhenbach on April 18 and Boganhausen on April 21. Because

Kessinger and I were at the front of our column when we stopped for the

night of April 22 at Margarethenried, we were among a group of perhaps

eighty men who stayed in a beautiful Catholic Church. The tiny church did

not hold all of us POWs, so some men spent the night on the church grounds

in a cold spring rain.

About April 25 we walked not far from Moosburg, the site of a huge POW

camp. We talked our guards into sending a small group of men to the camp

in an effort to get some Red Cross food boxes. When the men rejoined our

group with no food boxes, they reported the camp was badly overcrowded.

Though they got no food, they thought we were better off fending for

ourselves on the road than being imprisoned in that camp. A day or two

later the Moosburg prison camp was liberated, but by that time we had

walked to Untermachensburg on April 27, Inning on April 29, and Velden on

April 30. A light snow fell as we walked through Obertaufkirchen on May

1.

Intermittently for several days we had heard the sounds of artillery

shells exploding not far from us. Consequently, we knew the Allied advance

continued and it would

18

not be many more days before we were liberated. We

had always wondered what would happen to us when the Allied advance

reached us and overtook us. Would we be shot by our guards, German troops,

or German civilians? Would we be unintentionally bombed again by the U.S.

Air Force? Would we be caught in another artillery barrage? Would we be

caught in cross fire in no-mans land?

May 2, 1945, was a joyful day. Shortly before noon we

approached Gars-am-Inn, a small town on the west bank of the Inn River

thirty miles east of Munich. As we looked down on the town from high

ground west of it, we saw red crosses painted on the roofs of some

buildings. We saw the Inn River and a large metal bridge across it. As we

watched from a distance of less than half a mile, retreating German troops

blew up the center section of the bridge, dropping this section into the

river. We felt almost as if our guards had led us to the best spot from

which to see the action before us.

As we walked down a curving hill into Gars, we saw

that the red crosses were painted on the roofs of buildings in a monastery

or convent. We learned later the place was being used as a German military

hospital. We continued walking to the town square, which was only a short

distance from the Inn River and the impassable bridge.

We spent some time in the town square while our

guards and the ranking American POW, a colonel, discussed what we should

do. The guards wanted to walk several miles downstream where we could

cross the Inn River single file on a dam. They promised us a good, hot

meal on the east side of the river that night. Our guards had promised us

good, hot meals several times, but we had never gotten one. After a short

discussion our colonel told our guards that we were staying in Gars and

not walking any farther. The colonel told our guards quite bluntly that

this town, with red crosses painted on the roofs of some buildings, was

the safest place we had seen in months. The plainly-visible red crosses

gave us some assurance the town would not be bombed by either the German

or the Allied Air Force. The village of Garsam-Inn was probably the

largest place we had seen since we left Nurmberg.

The colonel told us POWs to spread out all over town.

He said if he gave an order to assemble, we should ignore it, because we

were staying in Gars. Kessinger and I walked a short distance and knocked

on the door of a home. When the housewife opened the door, we asked for

food. She invited us in and led us to her kitchen. She provided warm water

for us to use in washing, and she gave us some bread and jelly. What a joy

that was to wash and eat bread and jelly!!! Kessinger and I returned to

the town square in late afternoon and learned that our guards had

disappeared. We surmised they had thrown their rifles away and started

their homeward treks.

At dusk we heard the wonderful sound of American

tanks coming down the hill into Gars. Tanks of General George Patton's

14th Armored Division moved into town

19

without firing a shot, for which we were exceedingly

thankful. The tankers said they had planned to stop on the high ground

west of the village for the night, but when they saw red crosses on the

roofs of buildings and much activity in Gars, they sent a patrol into town

to investigate. The patrolmen found dozens of American POWs, so they

decided to move into town that night. We POWs celebrated our second, and

final, liberation !!!

My Military Service After I Was Liberated

The tankers threw off boxes of K-rations and

C-rations. We were almost deliriously happy as we ate army food again. But

because we were so hungry, we did not use good sense. We ate too much and

found that we could not keep food in our stomachs. On this occasion, and

for several days to come, we could eat very little without vomiting. The

tankers set up outposts around town, and we felt the safest we had felt in

months as we lay down for the night, our first night as ex-POWs.

On May 3 we former POWs practically "took over the

town. Kessinger and I took some army rations and cooked them in the

kitchen of a German home. About noon a column of trucks rolled into town.

I wrote a short letter to my parents to tell them I had been liberated. I

gave it to a tanker and asked him to mail it for me. This note, which my

parents received about the twentieth of May, was the first notification

they received that I had been liberated. In the afternoon we boarded army

trucks and were taken to the large prison camp at Moosburg, which had been

liberated about April 27. The camp was still crowded, and there was little

food, though I did get some white bread which tasted like cake. I slept

outdoors.

I was at Moosburg four days. I was sick some of the

time, because I could not keep much food down. We received Red Cross food

parcels and cans of insecticide powder for body-crawling insects. I got

rid of some of the lice that had been with me for several months. I mailed

another letter, the second since I was liberated, to my parents.

On May 7 we were taken by truck from Moosburg to an

airfield at Ingolstadt. The war in Europe ended while we were there, but

we did not know it at the time. Fifteen C-47 cargo airplanes landed and

took off with ex-POWs, but I was not one of them. Kessinger and I slept in

a German warehouse where some men picked up souvenirs. On May 8 C-47s flew

overhead all day long, but only one landed at Ingolstadt. Kessinger and I

slept on the airfield our last night in Germany.

Many C-47s landed at Ingolstadt on May 9. I boarded a

plane named "Ready Teddy" and we were airborne before noon. We landed at

Rheims for refueling.

For our benefit the pilot flew low over Paris and

circled the Eiffel Tower. This made several men sick to their stomachs and

they vomited. When we landed at LeHavre, the American Red Cross greeted us

with coffee and doughnuts. We traveled by truck about 45 miles northeast

of LeHavre to Camp Lucky Strike. I took only the

20

second shower I had in almost five months, after

which I was issued new clothing, for I had thrown my grimy lice-infested

clothing into a bonfire. My first meal was a small serving of creamed

chicken. I removed my clothing to go to bed for the first time since

December 15, and the G.I. cot was comfortable.

Camp Lucky Strike was a RAMP Camp (for Recovered

Allied Military Personnel). Other camps were named for other brands of

cigarettes. During the eight days I spent at Camp Lucky Strike, I sent a

cablegram to my parents, was interrogated by Military Intelligence about

my captivity, and was interviewed by an officer from the Adjutant

General's Department. We ate six small meals a day, getting our stomachs

accustomed to food again. After getting some injections and passing a

rather superficial physical examination, I was declared able to make the

trip home. Men who were unable to travel were either detained at Camp

Lucky Strike or sent to hospitals in England, depending on the severity of

their illnesses and injuries.

On May 17 we traveled by truck to a camp near

LeHavre, and the next day we heard rumors that "the convoy sails

tomorrow." On May 19 we traveled by truck to the harbor at LeHavre and

boarded the U.S.S. General William H. Gordon, a navy transport ship

commissioned in August, 1944. We sailed from LeHavre at mid afternoon and

joined a convoy in the English Channel. We were told we expected to arrive

in New York on June 3. On May 20 we saw Land's End, England, off the

starboard bow and said goodbye to Europe.

Much to my surprise, as we neared New York the

General Gordon changed course, sailed south, and after another day or so,

entered the beautiful blue Caribbean Ocean. On May 29 we sailed into the

harbor at Port of Spain, Trinidad, to unload a group of Air Force men (not

POWs) and their equipment. The unloading continued all day on May 30. On

May 31 we sailed from Port of Spain and were told the next port would be

New York City. On June 1 we sailed into the Atlantic Ocean about one

hundred miles east of Puerto Rico.

June 4, 1945, though misty and cloudy, was a

wonderful day. A Women's Army Corps band sailed into Lower New York Bay

and played for us as we approached New York. Because of the fog and

clouds, we could not see the Statue of Liberty welcoming us until we were

quite close. Like others, I wiped tears from my eyes. After we passed

Ellis Island, we could see the tops of the New York skyscrapers disappear

in the fog and clouds. Fire ships sprayed water high in the air as we

sailed past Lower Manhattan Island. A Coast Guard band played "Sidewalks

of New York" and military marches as the General Gordon docked at Pier 88

beside the Queen Elizabeth, on which I had sailed to Scotland in October,

and her sister ship, the Queen Mary. Pier 88 was the pier at which the

Queen Elizabeth was docked when I boarded for the voyage to Scotland eight

months earlier.

We disembarked, crossed the Hudson River on

ferryboats, and took a train to Camp Shanks, New York, arriving in time

for dinner. The menu for my first meal back in

21

the U.S. was steak, French fries, green beans, peas,

lettuce, celery, hot rolls and butter, cake and ice cream, and coffee or

milk. This was the best and most complete meal I had in many months. I

sent a telegram to myparents.

I spent the morning of June 5 being processed,

receiving new uniforms and receiving some back pay. At noon I left for New

York City. I remembered the New York POWs had said Lindy's served the best

cheesecake in the U.S. Consequently I went immediately to Lindy's to eat

this delicacy for the first time.

In the evening I went to the Paramount Theatre on

Times Square for 'A Salute to Major Glenn Miller" extravaganza. Miller, a

popular big band leader, had disappeared on a flight from England to

France on December 15, the day before the Battle of the Bulge started. The

program featured many well known orchestras, including Charlie Spivak,

Louis Prima, Count Basie, Sammy Kaye, Fred Waring, and Benny Goodman.

Vocalists included Tex Beneke, Jo Stafford, Perry Como, Kate Smith, Eddie

Cantor, Allan Jones, Diana Lynn, Cab Calloway, Pearl Bailey, and The

Modemaires. Other performers included drummer Gene Krupa, comedian Milton

Berle, tap dancer Bill Robinson, and an Air Force band. After the show I

returned to Camp Shanks.

In the late afternoon of June 6 I boarded a troop

train for Ft. Leavenworth. During a stop at Union Station in Kansas City

on June 8, I called home. With many other soldiers I arrived at Ft.

Leavenworth about 6:30 in the morning on June 9. After waiting for two

hours, I received the rest of my back pay and completed necessary

processing by eleven o'clock. I received sixty-three days leave and four

days travel time before I had to report on August 15 to the Park Hotel in

Hot Springs, Arkansas. I headed for Osage City via Kansas City, arriving

home on June 10.

A day or two after I returned home, my mother asked

me to drive her to Phyllis Grigsby's home. Mother wanted to return a

negative she had borrowed to make prints of a snapshot Phyllis had taken

of my parents. On this visit my mother introduced me to my future wife.

Phyllis was teaching music at Osage City High School and conducting a town

band for the summer. We had some dates during the summer. Marie Larson's

family owned a cabin on the Marais des Cygnes River fourteen miles south

of Osage City. One day we enjoyed a picnic at the cabin and a swim in the

river with Marie and Willis Tompkins, my friend from Templin Hall days at

KU and Marie's future husband. Phyllis and I attended several movies, and

we went to Meadow Acres Ballroom in Topeka to dance. When we spent a

weekend in Kansas City, Phyllis was impressed with the way I knew my way

around the city.

In August I went to Wichita to take an examination

for an Internal Revenue Service job, though I planned to return to school

when I was discharged from the army. While I was in Wichita, the war with

Japan ended. I reported to the Park Hotel in Hot springs on August 15.

During the several days I lived in the hotel on bathhouse row, I had

physical examinations, had some needed dental work done, brought my

22

army service records up to date, and enjoyed a hot

bath or two.

My next assignment was as a company commander in the

80th Infantry Training Regiment at Camp Robinson, Arkansas. Because I was

the fourth company commander the trainees had in their first six weeks,

discipline was a problem. I was promoted to the rank of First Lieutenant

on October 9. One weekend I accepted a ride with Virginia and Lynn

Kessinger to St. Louis to meet Phyllis. At this time we decided to get

married after I completed military service.

I received orders that I would be discharged from

service on January 8, 1946, and I would be on final leave from December 1

to January 8. I was extremely relieved when my successor as company

commander signed for the company equipment, because an inventory would

probably have shown that some of the equipment was missing, just as it was

missing when I signed for it three months earlier. I believe the company

supply sergeants had a way of passing equipment from company to company

whenever an inventory was to be taken.

I arrived home on December 2, my 23`d birthday.

Phyllis and I made plans to be married on December 28, though I had no

idea who would serve as my best man, because most men were still in

military service. A week or ten days before Christmas my brother, Warren,

called from New York. Mother told him, "Hung and get home because Martin

is getting married.' Warren gasped, "Martin? Who is he marrying?' Though

his outfit was quarantined, Warren was able to get home for Christmas with

his wife and our wedding.

Phyllis and I were married on December 28, 1945, by

Reverend Clower in the First Methodist Church in Osage City. Lavona Walden

(Dunworth), a teacher friend of Phyllis, was bridesmaid. Two of Phyllis'

high school students sang "My Hero" from The Chocolate Soldier and Irving

Berlin's "Always." Warren, a captain in the Field Artillery, was

resplendent in his uniform. Because I was still in the army, I wore my

uniform for our wedding and our honeymoon in Kansas City and St. Louis.

On January 8, 1946, my honorable discharge became

effective. In a few days

I returned to Lawrence and enrolled for the spring

semester at KU, knowing that Phyllis would join me in Lawrence when her

school year ended.

My enlisted man serial number was 17082968. My

officer's serial number was 0-551459. My POW number was 25330. My military

occupational specialty was #1542, infantry unit commander. The highest

rank I achieved was First Lieutenant. My military awards were Combat

Infantryman Badge, World War II Victory Medal, American Theater ribbon,

European Theater of Operations ribbon with three bronze battle stars

(Ardennes, Rhineland, and Central Europe), the Prisoner of War Medal, and

the Good Conduct Medal. In the army I was required to use my first name,

middle initial, and last name; therefore, I was Lloyd M. Jones.

23

Some Additional Thoughts

My service in the army in World War II, including my

capture and imprisonment, was a never-to-be-forgotten experience, "a

defining moment," but one I would not want to repeat. Nor would I want

others to experience what I did. I was young, resilient, and morally

strong. At the time I was captured, I was in good physical condition. I

learned to be mentally tough. I learned that a human being can suffer

inhumane treatment and become stronger because of the experience.

When people ask me how I could experience what I did

and not be bitter, I cite my youth, my excellent family background, my

faith, my youthful years in Osage City, my excellent education in Osage

City and at the University of Kansas, my sound military training, the

support I received from fellow soldiers, and my desire to see what would

happen in the next sixty years. The assistance we POWs gave one another

was significant. The support I received almost daily from my buddy, Lynn

Kessinger, was a tremendous help, as we encouraged one another to hold on

and keep going. He was one tough soldier, and from him I learned to be

tough. I was fortunate to have him as my friend and cohort.

My fellow commissioned officers in Company G were

Captain Edward H. Murray, First Lieutenants Wilbur H. King and Earl W.

Browne, and Second Lieutenants David R. Millice and Moms L. Patrizi.

Murray suffered a severe injury to his face and head, King was shot in his

neck, and Patrizi was shot in his side and captured a day or two after he

and Browne tried to escape in the Battle of the Bulge. Browne and Millice

were in the same prison camp near Berlin where Millice died of pneumonia.

Murray, King, Browne, and I returned to the United States. Neither Browne

nor I have ever known what happened to Patrizi after he was captured.

About 1995 Phyllis and I drove to Chattanooga,

Tennessee, and enjoyed a two-day visit with Gladys and !von York, Elaine

and Lee Darby, Maxine and Billy Moore, Lois and John Forsyth, Louis V.

Nardone, and Walter S. Adams and his wife. Darby, York, and Moore were my

squad leaders. Nardone, Forsyth, and Adams served in Company G, but not in

my platoon. Since then Moore, York, and Adams died. My platoon guide,

Sergeant Jesse Bishop, also died. My platoon sergeant, John Parchinsky,

was captured with the rest of us, but the Company G veterans listed above

and I do not know what happened to him after that. The last time I saw

Parchinsky was December 20, 1944.

The war years were difficult years for my parents,

especially my mother, who was not out among people every day, as my dad

was. Their three sons were in the army and in combat in Europe. Harold, a

sergeant in the infantry, was wounded and awarded the Purple Heart.

Warren, a forward observer in the Field Artillery, received two bronze

stars for heroism in combat. Fortunately, we all returned home, were

happily married, have wonderful children, and lived productive lives.

24

Epilogue

On two occasions in the 1980s, Phyllis and I retraced

most of the route I had taken through Belgium and Germany in World War II.

In 1983 we rented a car and toured the area in which I fought in the

Battle of the Bulge, including Born, St. Vith, Schonberg, Andler, Auw,

Radscheid, Bleialf, and the approximate spot where I was captured. By car

we traced my POW walking route from near Schonberg through Prum to

Gerolstein. We then drove to the Moselle River and followed the Moselle

River Valley to the Rhine River, past Koblenz to Diez and Limburg-on-the

Lahn.

We drove to Hammelburg and stopped in the town square

to ask directions to the site of the former POW camp. None of the older

men in a pub seemed to know anything about a former POW camp, but a young

man said to Phyllis, "Kommen, Mama," and he pointed to the road we should

take to reach the site. We drove up the long curving road that I had

walked with frostbitten feet on January 11, 1945. We checked our cameras

and passports at the entrance gate and visited the infantry training

center, which was on the site of the former prison camp. As a German

officer and his driver followed us, we drove our car around the training

center and saw several old buildings in which prisoners were housed in

1945. Because we were nervous without our passports, we did not stay long.

We claimed our cameras and passports at the entrance guardhouse and drove

to Camberg where we had reservations at a bed and breakfast.

On this trip we found the former home of the Theissen

family in Born, Belgium. The building, which was used to store building

materials, still had a trickle of water running under the house to the

basement where the sawmill had been. A French-speaking lady drew a rough

map for us so we could find the home of Johanna's nephew who was now

operating an all-electric sawmill near Recht, a nearby village. We enjoyed

coffee and a visit with Karl-Joseph and his wife, Nicole, in their home.

On a 1989 visit to Germany we traveled by car and

traced my walking route from Feucht to Gar-am-Inn, including visits to

many of the towns through which I had walked. The raft-like ferry was

still in operation at Weltenburg, and one morning we drove our car onto

the ferry and enjoyed a smooth, quiet crossing of the Danube River. A

gentleman eating his Sunday dinner at a restaurant in Pfeffenhausen left

his wife and son to get in his car and lead us five kilometers to

Boganhausen.

We found the beautiful, small church in

Margarethenried just where I told Phyllis we would find it. We enjoyed a

meaningful visit inside and in the adjoining graveyard where German

soldiers who were killed in World Wars I and II are buried. The only

commercial establishment in the village was a beer hall, so we stayed

overnight in a nearby town. In Moosburg we found a large park and play

fields where the prison camp had been in 1945.

25

In Gars-am-Inn we saw the monastery, visited the town

square, and drove across the Inn River bridge which replaced the one I saw

destroyed by German troops on May 2, 1945. In a small apothecary shop we

visited with a man who was eleven years old and living in Gars when he saw

the bridge destroyed. He said he remembered seeing the POWs walk to the

town square a short time after the bridge was blown up. I told him I was

one of those POWs. He told us his ten-year old daughter wanted to go to

Florida.

On two visits to Belgium we visited Johanna Theissen-Serexhe

in her home in Fleron, near Liege. On both occasions we stayed in the home

of Daisy and Harry Poels in Brunssum, Holland, and enjoyed their

hospitality. In 1983 I drove and Johanna directed us to Spa, Belgium,

where we enjoyed a delicious meal in a French restaurant in a casino. We

returned to Johanna's home for a short visit before driving to Antwerp. On

this visit Johanna cried and was unable to tell us much about her sister,

Gertrude, who was shot and killed by German soldiers on the morning of May

10, 1940, the day Germany invaded Belgium, Holland, and France. Later

Johanna told us Gertrude was the first Belgium civilian killed by German

soldiers when they invaded.

In 1987 we visited friends in the south Limburg part

of The Netherlands. Margaret and Harold had introduced us to their

friends, Daisy (LeRoux) and Harry Poels, Emma and Matt LeRoux, and Tos (LeRoux)

and Gerard Durlinger. Harold had stayed in the LeRoux home for a few days

in 1945. After visiting in the Poels' home in Brunssum, Daisy, Harry,

Emma, Matt, Phyllis, and I drove in two cars to Johanna's home in Fleron

for coffee and a visit.

With Johanna driving her car, we had a three-car

caravan as we drove to Chaufontaine for lunch. Johanna led us on a tour

which included the beautiful American Cemetery high on a hill near Henri

Chappelle, Belgium, where some men from Martin's Division are buried.

Johanna got us through the check point at the German border and we visited

Monschau in a light rain. We drove to a trout restaurant on a small stream

near Hofen, Germany. The restaurant was operated by Johanna's cousin, Otto

Theissen, with whom she did not speak for many years after the war because

they were on different sides in the conflict. However, after a delicious

trout dinner, Johanna, her cousin and his wife, and our four Dutch friends

had no difficulty speaking with great animation in Dutch, German, and a

little French. Phyllis and I enjoyed listening to them and watching them.

On two occasions we visited Johanna when she was in

the United States, once in Michigan and once in Washington, D.C. We still

communicate with her.

We have communicated with, and exchanged home visits

with, Lynn Kessinger and Earl Browne and their wives since World War II.

We still communicate with them and with Elaine and Lee Darby, Maxine

Moore, and Gladys York.

26

Here are some quotations from "A War to Be Won:

Fighting The Second World War," by Williamson Murray and Allan R. Millett