|

Wacht am Rhein (Watch on the Rhine) My experiences during the Battle of the Bulge Pete House |

|

HISTORICAL NOTE: In July. 1944, after the Allied breakthrough in Normandy Hitler started planning a way to stop the Allies. This operation was code named Wacht Am Rhein by Hitler. The German Army would mass several Armies to break through the Ardennes and attack towards Antwerp. This would separate the Americans from the British. hoping that England would ask for a separate peace. The idea did have merit as there was no love lost between Eisenhower and Montgomery. As the plan evolved it pointed at a thinly held line running north-south some 90 miles in length in the heavily wooded Ardennes. By December 10th this line was defended by the American 99 Infantry Division on the north. 106 Infantry Division in the middle and 28 Infantry Division on the south. These three divisions were spread so thin that there were very little in reserve. Because of the difficult terrain it would be difficult to bring tanks up to support the Americans. In addition the area between the 99 and 106 had no infantry but was assigned 4o the 14 Cavalry Group (their training and mission is recognizance not to hold a line.) The area around, the city of Losheim, is called the Losheim Gap and is the only logical way thorough the Ardennes. In 1914 the Kaiser sent his armies and in 1940 Erwin Rommel led his cavalry through this same Losheim Gap. To make things worst the Allies were greatly restricting all supplies to build a stockpile for the spring offensive. This fact greatly limited effective fire on the Germans. Against these three American Divisions the Germans were able to mass the 15th Army. 6th Panzer Army, 5th Panzer Army. and 7th Army (a 9 to 1 ratio).

The Battle of the Bulge lasted from December 16, 1944

until January 25, 1945. More American troops were involved than in any

battle in history. Almost one forth of the Americans held prisoner of

war during World War II were captured in this epic battle. Almost one fifth of all Americas captured from World War I to the present time was during this great battle. 28% more fatalities than both armies at Gettysburg.

This is my story. I was a machine gunner in A Battery, 590th Field Artillery Battalion, 106th Infantry Division. I was a trained battery clerk, supply sergeant, motor mechanic, truck driver, battery agent, wire man, cannoneer, motion picture projectionist, but never fired a machine gun! Great organizational skills somewhere!

All the artillery and engineer units of the division left Boston November 10, 1944 on the Coast Guard Transport Wakefield and arrived in Liverpool on the 17th. The rest of the division had left the States a month earlier. We were transported by train to Glosfer Reservoir Reservation where we received most of our trucks, guns, and other equipment. Some of the new equipment and clothing never caught up with us. Did receive the new combat boots and two pair of English wool socks. It is very possible that in some forgotten warehouse listed under our division shipping order number 2001 is the rest of our gear.

We did not receive my truck until two days before we left

Glouster. We were able to get the sides and tarp rigged although one of

the fop bows had short legs. Did not have time or the tools to install

any of the 50 cal. machine gun cab racks. And, of course, the truckís

oil was never changed although the red tag said to change all oil before

driving over 50 miles! On November 29, half of the 590th Field Artillery boarded the LST 517 (Landing Ship Tank) for the short trip across the English Channel. After a rough channel crossing we anchored off the mouth of the Seine River. A very bad storm hit us. Many of the crew and soldiers became sea sick. In addition, diarrhea broke out! It was almost funny to see some men with their heads hanging over the rails while others were mooning the sea the while the sea water and snow was blowing every where. I had a difficult task climbing the ladders three decks up with my carbine and mess kit. The Navy corpsman said I had asthma, a hell of a time to find out. One of the men developed severe stomach cramps so they brought our battalion surgeon, Dr. James Yamazaki, over from the other LST. The man had pneumonia.

Finally on December 7, after a full week on the North Sea, we sailed up the Seine River to near Rouen where we left the ship the next day. We were six days behind the rest of the battalion. Our column then drove to a small village where we waited for travel instructions. Fortunately the natives were friendly and the cognac and hard cider flowed like water. Left this friendly village sometime that night. Turned out to be the last friendly natives I encountered in Europe. The rest of the night was miserable. It rained then froze. Very cold. No food. The roads became very icy and slippery.

DECEMBER 9, 1944 SOMEWHERE IN FRANCE

The next morning Warrant Officer Collins stopped his lead jeep and moved behind it. The third truck couldnít stop because of the ice. Our first fatality. It seems someone in command should be held accountable for allowing us to drive without chains. As soon as the British Royal Engineers put sand on the road we moved out. No food since breakfast on the LST the day before.

Pulled into a field where we spent the night. My truck was sent somewhere without me. Had to spend the night without my tent or blankets.

DECEMBER 10, 1944

After dark was told to mount the four truck cab ring mounts for the machine guns. Took most of the night as we had to remove all the grease with gasoline (the weather was well below freezing) and didnít have any drills, saws, hammers or other tools. The mounts would never have held up if the machine guns were fired. Why didnít our artillery mechanic do this job?

DECEMBER11, 1944

Moved out in the morning. Later that day the column stopped in a town. Tried to purchase something. Only had French Francs. Store wouldnít accept it. Must have been St. Vith. Pulled into a field that night. Believe it was near Schoenberg.

DECEMBER 12, 1944 - BELGIUM We abandoned two of our 6 x 6 trucks (used to haul the 105 howitzers) because they had no power. They were supposed to be new when we received them in England. Four of us had to stay behind to guard the tires and cargo. Not provided with food, bedding, cover, no way to build a fire, nor did we know where we were or where the battalion was heading. Did not arrive at the battery position until after dark on the 12th.

We were fed and assigned to a vacant farm building with a 50 cal. machine gun and told to shoot at anything that moved. It had been six days since we had been able to sleep so we built a fire in the stove and went to sleep.

DECEMBER 13, 1944 - OBERLASCHAD

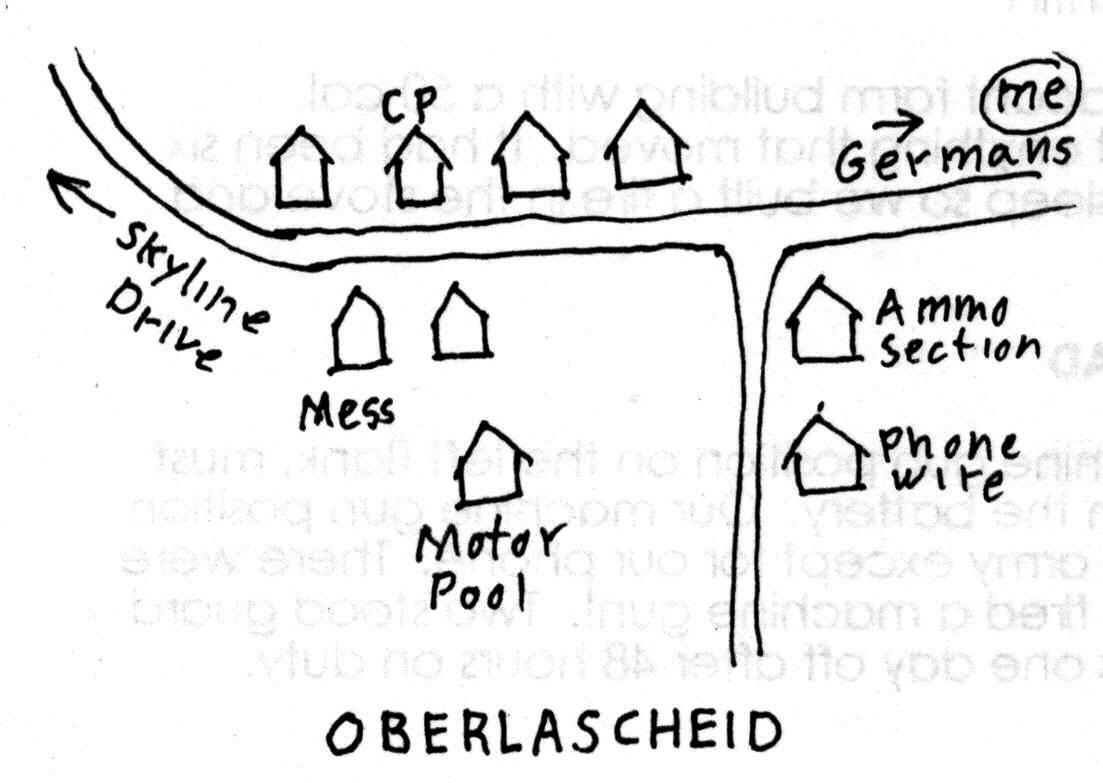

Next day assigned to 50 cal. machine gun position on the left flank, must have been at least 500 yards from the battery. Our machine gun position was completely isolated from the army except for our phone. There were three of us, and me never having fired a machine gun!. Two stood guard around the clock. This allowed us one day off after 48 hours on duty. Somehow it didnít seem fair.

Food, ammo, and gas never seemed to catch up with us. From the day we arrived in England the only time we had enough to eat was on the LST. At Oberlascheid things did not get better. Never enough food and requests for fire missions greater than our supply of 105 shells (and what good is artillery if there are no shells?). Our only supply road, Skyline Drive, was exposed to German observers and received constant shelling when used. So the road was only usable on dark nights.

For survival in northern Europe in the winter all we had was our regular issue of two blankets, overcoat or mackinaw, long johns, wool cap and gloves, and regular wool uniform. From what I saw later on in German camps the 28th and 99th divisions were in the same shape.

In the woods outside St. Vith S/Sgt. David Vance brought up a supply of one extra blanket (this now gave us 3 blankets), old style wool ~iress coats, and some used overshoes. Nothing like the gear we saw on other troops. The rumor had it that in a couple of weeks we would be rotated back for warm new winter gear.

DECEMBER 15 - OBERLASCHEID

December 15th, 1944, began as a cold overcast day in the

tiny West German border farming village of Oberlascheid. The village was

a part of the defenses built by the Germans before World War II. The

night before had been unusually busy for the gun crews of Battery A.

This part of the German front was considered a rest area as little

fighting was supposed to take place. I guess someone failed to tell Herr

Hitler. After all what commander in his right mind would attempt an

attack in the most mountainous area in this part of Europe!

This Schnee Eifel area had few roads. Schnee Eifel means

snowy mountains. It was crossed with many rivers and streams that would

block a mechanized army. Of course the Germans attacked France through

this same Schnee Eifel in 1940 when they drove the British across the

channel and defeated the French. They also used this corridor with great

success in 1914 to start the First World War

Our wire (telephone) section was housed in the same

building as the German caretakers. One night when the switchboard

operator went to relieve himself he saw all the Germans going down the

stairs to the basement. Immediately after we received German artillery

fire. It must be assumed that the German caretakers were in direct

contact with the German army. We believed that all our telephone lines

were tapped, that is they were monitoring our communications.

During darkness enemy patrols moved throughout our area. Our orders were to fire at anything that moved after dark. This meant everyone stayed put at night.

After firing over 100 rounds that night, our 105 howitzers ran out of ammunition and had to wait until after dark the next day for a re-supply. Each round weighed 26 pounds and was 4 inches in diameter. Other than that the day was normal in Oberlascheid. Cooks served the usual three hot meals. It was my day off, the first free time since leaving the LST December 7th, so I heated my helmet full of water to shave and bathe. Afterwards I thoroughly cleaned my carbine, and took out some windows in town to add a covered observation area to our machine gun post.

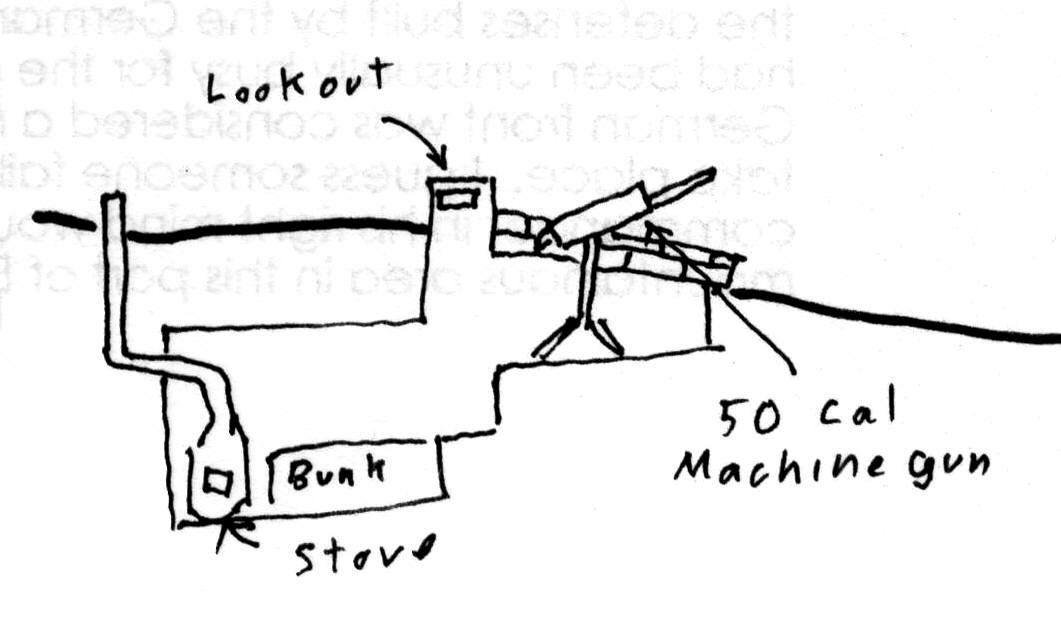

In the evening I relieved one of the men at my outpost.

We were in a plowed field about half a mile down a sunken road towards

the German lines. Our homemade bunker was about 4 by 8 feet connected to

a gun pit about 8 feet in diameter and two feet deep. For heat we burned

wood in a large milk container with a hole cut in the side. Our weapons

included a 50 caliber machine gun on an anti-aircraft mount and a

bazooka (anti-tank weapon). Our job was to alert the battery of an attack. In case of a tank attack we were supposed to fire our machine gun to make the tanks close up their hatches until our own guns could be turned around to kill the tanks.. The outpost was expendable. Sometimes with our binoculars we could see the Germans across the valley in their chow line. Of course they could see us! All in all it was a dumb position but when we relieved the 2nd Division the orders from 1st Army were to take over existing fox holes and gun positions. Division Commanding General Alan Jones was told not to make any changes.

The Germans had a V1 rocket launcher just to the east of us. These slow rockets passed very low over our position. We were ordered to shoot them down with our 50 cal. machine gun. We knew better. The Germans got very upset when you fired at their toys. The 333rd Field Artillery Group was to our rear (west). We saw them fire with their quad 50 cal. and they received a lot of German counter battery fire. Rumor had it that they were badly mauled.

DECEMBER 16 WACHT AM RHEIN

Dawn of December 16 began with massed firing by the Germans. One 155mm shell knocked a sandbag into our machine gun position - but it was a dud. The shelling cut our only link back to the battery, a telephone line. The wire crew ran a new line late that morning and we were again in touch with the world.

Shortly afterwards battery commander, Capt. John Pitts, followed the wire to visit us. He talked about making a number of changes in leadership. Capt. Pitts asked me if I would serve as supply sergeant. I said yes.

The Germans hit us hard with artillery fire that afternoon. Battery commander, Capt. Pitts, was killed. With the increased enemy activity our third man rejoined us. A second 3 man 50 cal. machine gun crew arrived to reinforce the outpost. We dug in deeper and prepared for more enemy patrols or a full German breakthrough that afternoon.

Later that afternoon we could see some of our own troops move out from between the Germans and ourselves. It was a very lonesome and frightening experience. We were able to get chow that afternoon, the last time our cooks functioned. Before dark the other machine gun crew was ordered back to the battery area.

After dark the battery executive officer, 1st Lt. Rex Roden, called on the phone and asked me how long it would take to move our gear. He said that A battery was getting ready to move into a better defensive position. We said it would only take about fifteen minutes, but we needed a jeep to move all our gear.

Shortly after that the phone line went dead. Because of heavy enemy patrols the orders were to shoot anything that moved after dark we stayed put until daylight. Would we be over-run by the Germans? Did the battery pull out that night? Were the three of us the only Americans in front of the Germans? It was a long frightening night.

DECEMBER 17 - OBERLASCHEID When it became daylight on December 17th I ran back to the battery command post in Oberlascheid. The battery was still there but getting ready to pull out. We found out that during the night some idiot wondered what the extra wires attached to the command post phone were for and disconnected them. Thatís what happened to our only communications with the world!

Ran back to our outpost to get the rest of the crew. Battery would not give us a vehicle so were only able to carry our carbines and the machine gun. Thus began our Battle Of The Bulge or as the Germans called it, Wach Am Rhein (Watch On The Rhine).

The German army knew the location of every rock and stream and could drop a shell wherever they wanted with great precision. Each time we moved into position and fired our guns the Germans quickly located us and would fire back. We totally changed our procedure. When orders for a fire mission came in everything was packed and trucks brought to the guns. As soon as the firing was over it was move like hell because German counter fire would be incoming. We followed this pattern the rest of the time.

DECEMBER 18 - WACHT AM RHEIN

After an early morning fire mission A battery was quickly moved to escape German counter battery fire. During the day we fired and moved several times. On one such move I was in a weapons carrier with the battalion executive officer reconnoitering for a new gun position. We were driving down the road with infantry walking along each side of the road. All of a sudden one of the infantry men yelled that there were no Americans in front of us. We continued to drive. I thought this was crazy. If there are no Americans then there must be Germans! We stopped near a small village and the survey officer walked into a field to our right. The snow had melted and the sod had popped out in hunks about a foot in diameter. A mine field we yelled at him. He put A battery on the left. The village turned out to Oberlascheid, where we started from two days earlier.

By this time the Germans had cut all communications from our combat team to division headquarters in St. Vith, Belgium, to the west. The last we heard was that the 9th Armored Division was moving up to support us and we were to receive an air drop of ammunition and food. Now, two of the 106th Infantry Divisionís three combat teams, The 422nd and 423rd were surrounded. We were part of the 423 Infantry Combat Team.

The 18th ended without further damage to our battery. It was move, dig in, fire, and quickly move. We were exhausted, hungry and cold. Cooks had not prepared any meals since the morning of the 16th. I received no emergency rations. Cold weather clothing and bedding was never issued.

That night we moved to an open field. We only had four rounds for our 105 mm howitzers left. We received orders to destroy all the equipment and be prepared to hike back to our lines. It was with great pleasure that I destroyed two 610 FM communications radios with a pick as they had rarely worked.

Then we received orders to get the vehicles running and move out. Only three of our large trucks used to tow the howitzers could be started so a 105 mm howitzer was hooked to the 3/4 ton weapons carrier I was in. We spent the rest of the night in our trucks on a road in a valley - totally useless. Every so often we would move forward a little. I walked ahead of the driver so we would not run over anyone. He had poor night vision so I took over as driver. It was bitter cold. Still no food.

DECEMBER 19 - THE END OF A BATTALION

When it became daylight on the 19th we moved up a steep field to the left and went into firing position along the edge of the woods - with only four rounds.

I opened a can of pork and gravy that we borrowed from the navy while on the LST crossing the English Channel and was heating it when the Germans hit us with everything. Of course I should have dug a fox hole. One of the guys had borrowed my shovel so I ran into the woods looking for a stream bed for protection. Left behind were my wool gloves and hat, and my mackinaw. This loss haunted me for the rest of my time in Europe.

When the Germans lifted the barrage Joseph Krouse, a fellow member of battery A, came by and said we were surrendering. We moved through the woods until we reached a clearing where we saw our battalion commander Lt. Col. Vaden Lackey and the commander of the 423 Infantry Regiment, Col. Cavender.

They told us that they were surrendering and we could try to fight our way out if we wanted. About 20 of us started running to the west. Lt. Creel and Krouse were the only other people from our Battery.

Our impromptu group must have run for about two hours towards the west. We did not see a single person. The terrain was very mountainous. We crossed two small fields before climbing a very high ridge. As we went down the west side of the ridge the deep forest gave way to very young trees about 5 feet tall.

Then we received a very intense fire from what turned out to be German 20 mm AA guns. At least three men were hit. Do not know if anyone was killed. We were isolated in the grove of young trees. Lt. Creel stood up waving his handkerchief. He was almost hit. Then the Germans stopped shooting and we moved down the open field towards the road. Some of the Germans met us and escorted us down the hill to the road. They were mostly teen age artillery men.

We carried the three wounded men with us. Donít know how many dead or wounded were left in the woods. Of course we were searched. They let me keep my pocket knife, watch, and overshoes. Treated us good - but no food.

Krouse had a D bar (a very large chocolate type bar) that he shared with me. This was the first food I had since the 16th.

Some of us were ordered to prepare the AA guns for moving. One American refused saying that it was against the Geneva Convention. The German officer pulled his pistol and shot him in the head. Thatís when I

learned to forget the Geneva Convention. The Germans organized us into groups five across by twenty deep. This was to become the standard way they counted and moved us. Carrying our wounded piggy-back we marched to the South until we reached a town (this may have been Bleialf) where we left the wounded.

We did not receive any food or drink. The guards would not allow us to get water or snow along the road. Said it would make us sick. I am sure they were right.

I had always heard that the German Army was very mobile. It was a complete shock to see so much of the artillery drawn by horses, and armored infantrymen riding bicycles. And the field kitchens preparing the hot noon meal. They looked like hot tar pots that we use to prepare roofs, and they were drawn by horses. As we were marched to the east the roads were packed with German men and equipment being moved to the front.

It was constant scrambling off the sides of the road to get around the German military gear then back into formation. I was very hungry, exhausted and my left foot was bleeding inside my boot from being rubbed raw. There was a German warrant officer in charge of our group. He was driving a small car like a VW. He would get behind and then when the road cleared come racing up blowing his horn to get us out of his way. Finely I refused to move. He got mad, pulled his pistol and aimed it at me. We were alongside some Tiger tanks belonging to the SS. An officer in one of the tanks cocked his machine gun and said something in German. The warrant officer put his pistol back and drove off. I owe my life to that SS officer with the silver skull on his hat.

Arrived in Prum, Gr. after dark. Prum had been heavily bombed and shelled. We were moved into the college building. We asked the guards about food and warm clothing. They said we would be supplied the next day. This was a pattern that was repeated often. Spent the night in a lecture hall on the second floor, and had to sleep on the stone floor - no glass left in the windows! It was a very cold and long night and me with only my field jacket - no overcoat, muffler, gloves, wool cap.,

DECEMBER 20 - PRUM

The Germans did not seem to be in a hurry to get us up. There was a science preparation room next to the room where they locked us. I found a screw driver and some electrical wire. I took this material because James Hill, one of my buddies, had a crystal for a radio. The room made an excellent latrine - plenty of floor space.

Later in the morning we were lined up in groups of 100 and marched towards the east. We only stopped once that day. Our guards carried bread, sausage, and margarine and would eat while on the march when hungry. The farmers had sugar beets piled along the road. I took one and ate it, a little at a time.

You could tell that the German economy was in bad shape. Almost every truck was towing another to save fuel. Many trucks had rigs on the rear or in a trailer where they heated wood in a sealed compartment with a wood fire. When the wood got hot gas was released that was piped to the engine. After dark we arrived at Gerolstein where we received a drink of some hot fluid, either ersatz coffee or tea. I ended up on the second floor of a wire basket factory. It was great - so many bodies that it was actually warm. Didnít dare to take off any clothing, it would be stolen. There were just too many people to lay down comfortable. Others, less fortunate, bedded. down in mud in stock pens outside.

DECEMBER 21 - GEROLSTEIN

The next morning we were moved outside. Each four people received a hunk of bread and can of what seemed to be corned beef. Broke the tip off my pocket knife opening the can. Germans said that until we were registered as prisoners with the Red Cross they could not give us regular food or clothing.

Again lined up in groups of 100. There were thousands of prisoners on the road through Gerolstein. The townspeople were out looking at us. Most appeared very sad.

There was a small park next to where we were standing. The prisoners used it as a giant relief station. And the townspeople standing around and watching. Almost funny squatting in front of women and children.

The guards did not seem to be very concerned about us moving around. I started walking along the column and located about thirty people from A battery and we got together.

One of the guys, Rusituto Corporlo from Los Angeles, became sick and I took him back to the factory office to find some help. Of course I could not communicate with the Germans. Finally got someone to look at Rusituto. When I returned to the column the other Americans would not let me get back in my group because they had been recounted so had to move to the rear of the long column. From then on was with people I did not know.

Finally we were moved to the train station. It seems that the Germans were unloading fresh troops and horses from box cars and loading American prisoners of war for the trip east. A German infantry colonel stopped me and asked about the 106th Infantry Division. He seemed to know a great deal about us. I did not have on any insignia. Very strange.

They put 64 of us in my box car. These box cars were very small. In World War I the Americans called them 40 and 8ís - their capacity was 40 men or 8 horses. With careful organizing everyone could sit if we sat in rows front to back.

The previous occupants had horses in one end. It was easy

to tell - the

straw

was

wet and had pies. Our box car had two small windows. They were open

but

covered with barbed

wire

- our

first introduction to German

barbed wire. One of the men had finished reading a paperback and gave it to me. I read some of it an put it in my back pocket. Later on this became my lifesaver. It probably did the work of at least ten rolls of toilet tissue during my interment (toilet paper was never provided). No, I didnít finish reading the book.

We left Gerolstein that afternoon and crossed the Rhine River - the first American Division to cross. (Is there some sort of ribbon or medal for that?) That night we stopped outside of Limburg.

DECEMBER 22 - LIMBURG

The day began cold and clear. To the south of the tracks was a large factory. The train was stopped in a railroad marshaling area. Must have been at least twenty tracks wide. The tracks and trains showed signs of heavy bombing. Bomb craters and destroyed locomotives and other railroad equipment were everywhere.

Our Air force bombed us today. Car behind us was hit. Donít know what happened to the people. The guards would leave before each bombing attack but would not let us out of the cars.

Several times the guards let a few people out to relieve themselves. Otherwise we used a helmet, and the window.

That night the RAF bombed the factory. Itís a very scary feeling to be bombed day and night by your own people and no where to hide.

No food or drink again today.

DECEMBER 24 - ALIVE STILL AT LIMBURG

Again cold. The RAF Lancasters again bombed the factory during the night. Our air force bombed the factory during the day. Some bombs hit around the train. We broke the barbed wire from one of the windows with a helmet and I climbed out and unlocked the door so we could run to the ditches for protection. When the guards returned they were very upset and threatened to shoot us.

That afternoon a civilian came along the tracks with buckets of water. He brought two buckets of water to our box car. Other than receiving the water it was a very bad. It has been eight days since my last meal, and not much water. Fortunately due to no food and little water most of our systems had shut down - little left to void.

After dark we prepared for another night of bombing. Several men had candles that lit up inside the box car. We sang Christmas Carols - yep it was Christmas Eve. We had both Catholic and Protestant services and settled down. Then loud banging on the doors. The Germans yelled to douse the candles and opened the doors. They provide us with bread, margarine, and marmalade. They returned with the ersatz hot coffee or was it tea. What a great feeling. Yes, Virginia, there really is a Santa Claus.

Then the train began to move. We sang more carols. If moved all night. No more bombing. This had to be my best Christmas Eve ever! DECEMBER 25 - CHRISTMAS DAY AT BAD ORB

During the night the car became very cold. The box car was made of wood with bolts going through to the outside to hold it together. There was over an inch of frost from our breath on each of the through bolts on the inside of the car. The train stopped and started backing up. We backed up to the end of the line at the small summer tourist resort town of Bad Orb.

We were ordered out of the box cars and lined up in the usual groups of 100 men. Some 400 in all. The train went back down the mountain. We just stood there - and stood there in the bitter cold. About noon another train backed into Bad Orb with another batch of 400 men.

Many of the good citizens of Bad Orb were dressed in their finest clothes as if having left church or going visiting (Remember it was Christmas Day). They were very sad. We felt that they were our friends. Even the guards were nice. It looked like the town earned money from timber and tourists. There was even a large Coca Cola Sign. However, we were the wrong kind of tourist - no money.

We were then marched through town to Stalag (Army Prison Camp) 9B. It was about 5 miles up to the mountain top where the prison camp was located. A very tough march in our shape. Stalag 9B was almost empty. A few Russians, Serbs, and black empire troops from South Africa. Our group of some 800 were the first of some 2,500 Americans to be kept here. My guess is that in excess of 4500 Americans were here at one time or another.

It was a great feeling. At last we would be registered as prisoners of war. We would receive warm clothing and food. We would be living in warm barracks. WHAT A JOKE!

Life in Sta lag IXB, Bad Orb, the worst of the worst, , is another story.

NOTES: Much of this material came from the diary I kept while in the German Prison camp. My thanks to fellow ďAĒ Battery memb~r Raymond Brown of Leeds Utah for some of the dates. |

| Page last revised 11/28/2006 |

The

tiny farming village of Oberlascheid had about twenty houses. The allied

military government allowed one family to stay and tend the live stock.

The various sections of A battery were housed in the empty farm houses.

Our fifth section (ammo and machine guns) used a house at the

crossroads. James Hill and I shared the upstairs bedroom. Not bad except

no heat and no glass in the single window. We had a fine feather bed.

Only used it one time, on the day before the battle began.

The

tiny farming village of Oberlascheid had about twenty houses. The allied

military government allowed one family to stay and tend the live stock.

The various sections of A battery were housed in the empty farm houses.

Our fifth section (ammo and machine guns) used a house at the

crossroads. James Hill and I shared the upstairs bedroom. Not bad except

no heat and no glass in the single window. We had a fine feather bed.

Only used it one time, on the day before the battle began.