(If

you wish to print this display of my experiences,

there are no links to other pages within the story.)

The Service Diary of

German War Prisoner #315136

Der Militardienst

Taschenkalender

des Kriegsgefangnen #315136

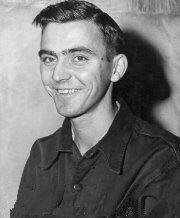

Sergeant John

P. Kline 35730410

Company M, 423rd Combat Infantry Regiment

106th Infantry Division

Army of the United

States

Squad Leader, First

Platoon, Second Squad

Heavy Machine Gun

The 106th Infantry Division

Battle of the

Bulge 1944-45

UPSETTING THE GERMAN TIME TABLE

The battle is known to the American soldier as The

Battle of the Bulge. To the German

soldier as Wacht am Rhein (Watch on the Rhine),

to the Belgians it is known as The Battle

of the Ardennes.

We were known as the

Golden Lions, because of the shoulder insignia we proudly wore. We were

ready, we thought, to handle whatever came our way. We were young, brave

and with honor. We have no reason to apologize to any person, State or

Nation for the way we conducted ourselves in battle.

The Golden Lions of

the 106th Infantry Division, due to the surprise attack, may have taken

a few faltering steps in those snowy winter days of mid December 1944.

Yet, as the German High Command soon realized, those young Golden Lions

were capable of recovering and fighting fiercely.

As after action

reports of the Battle

of the Bulge were reviewed, they showed that the 106th Infantry Division

played an important role in the outcome of the battle.

Hitler's orders were

to bypass all pockets of major resistance. His main objective was

Antwerp with its supply depots. He wanted his

troops to capture bridges on the Meuse

River as quickly as possible.

His first objective,

in the 106th's area, was to take St. Vith and its network of roads. He

underestimated the time that it would take to overpower the Golden Lion

Division.

Entrenched high atop

the Schnee Eifel, the 422nd and 423rd Infantry Regiments of the 106th

Infantry Division were bypassed on the North and south flanks. However,

they chose not to stay in their positions. Instead, they withdrew and

engaged the enemy, who had closed the pincers behind them at Schönberg.

In doing so, they kept the enemy occupied during the crucial hours at

the start of his counter offensive.

The delay which

resulted from their action, combined by the stubborn resistance of the

424th Infantry Regiment to the South, blunted the enemy's drive. The

Germans burned precious fuel, wasted troops and lost time that would

never be recovered.

In the final

analysis their resources and time ran out.

The days lost and the men sacrificed, cost the Germans more than they

had bargained for.

The 106th's resistance contributed to an early finish of World War II.

Winter 1944-

This year also, Spring

will come

to beautify the earth.

The glory in each icy

clod

even now awaits its birth.

Spring will come to

this hurt land.

Its face will then be gay.

This splendor latent in

each bough

will swell, then burst and sway.

Winter yields each

year to Spring

its natures rule, so be it.

Even this year Spring

will come

and some of us will see it.

The poem above from

"Before the Veterans Die"

In

Memory of: it’s author

Dale R. Carver (Died 14 Oct 2001)

formerly: Ammunition & Pioneer Platoon Leader

1st Lt., 424th Combat Infantry Regiment

Headquarters 3rd Battalion

106th Infantry Division

Awarded the Silver Star for gallantry

in action against the enemy.

The Service Diary of a German War Prisoner

#315136

Author John P. Kline

published and edited by John P. Kline

© Copyright by John P. Kline 1987-2002

On

December 16, 1944 the

German Armies under Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt mounted a massive

counteroffensive, historically known as the "Battle of the Bulge."

The Germans called it Wacht am Rhein, The rest of the Europeans

The Ardennes Offensive or The

Battle

of the Ardennes.

The

springboard for this counter offensive, started with a thrust through

the Ardennes

Forest,

into Belgium.

Their battle plan was to occupy the town of

St Vith [a

road center], then push through to the primary target,

Antwerp,

with all of its fuel storage depots. Hitler thought this would deal a

demoralizing blow to the Allied forces. He wanted to shame the Allied

command and politically convince the Allies to stay out of the German

Homeland.

The 106th

Infantry Division, when they caught the brunt of the German offensive on

16 Dec. 1944:

--

Had been on the Continent only 15 days.

-- Had been placed in a "quiet" sector for orientation.

-- Had the youngest troops (average age - 22) of any American

Division.

-- Had been in their front line positions only 5 days.

-- Had no prior warning the Germans were preparing to attack.

-- Occupied a front line that covered at least four times the

normal distance.

So fierce was the

German onslaught that the 106th Infantry Division had the dubious honor

of being hit by a greater concentration of enemy strength than any other

American Division in the war. In a single brief engagement the 106th

suffered more losses than any other American division in World War II.

Two of its three

Regiments the 422nd and 423rd Infantry Regiments, isolated from other

Allied troops, were liquidated within three days after the German

Offensive started. Its third regiment, the 424th, continued to carry the

banner for the 106th and fought proudly through to the end of the war.

Early in January of

1945, Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson announced the casualty list for

the 106th Infantry Division. The totals - 416 men killed in action,

1,246 wounded and 7,001 missing in action. Over 60 percent of the

division's personnel were dead, wounded or captured. Actually the 106th

Infantry Division suffered 641 Killed in Action from the start of the

Battle of the Bulge until the end of the fighting war.

Captured December

19, 1944, on a hill overlooking Schönberg, Belgium, I was one of the

7,001 that was missing in action. During my captivity I kept a diary.

Eighteen pages in length, the diary was stored in a cigar box for all

these years, along with a few MIA telegrams, V-mail letters, and other

war memorabilia. Occasionally, I looked through the old cigar box and

leafed through the diary. Each time thinking that I should make it more

readable, by putting it to print.

I finally decided to

preserve the information for my family and grandchildren.

The old diary has

enabled me to revive my memory and retrace my steps. I have been able to

preserve the events of those days for history and my family. Other

historic events since World War II have brought back memories of those

days.

One such event was

the return of the American prisoners from Vietnam. The sight of the

returning prisoners walking down the ramps, to meet their loved ones,

brought my emotions to the raw edge. It reminded me of the day in 1945

that I returned home as a liberated prisoner. On that day, I stepped off

a Greyhound bus to walk and run 12 blocks to my home. There, to join my

wife, my 9 month old son and my parents. That was a day that I shall

always remember. The last few months, (this was written 1987) as I have

searched my memory and expanded on my dairy, have not been without

emotion. In my mind, many of the episodes and happenings of those days

once again became real.

In 1977 after 34

years of marriage, my first wife died of Cancer. She had, in August of

1944, delivered our first son. Then, in December 1944 she suffered

through news of the collapse of the 106th Infantry Division during the

Battle of the Bulge. Then along with my parents suffered the

suspense of the "Missing in Action" telegrams. Finally, rejoicing with

me in a happy return. Later, she gave me two more sons. Our sons, in

turn, gave us four handsome grandsons. Then one granddaughter, one step

granddaughter and one step grandson. (1999).

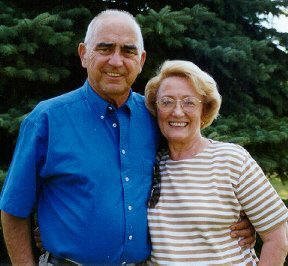

A photo of Bettie and I before I went to service in 1943.

A trip to Shakamak State Park, Indiana just before leaving for service

in the Army

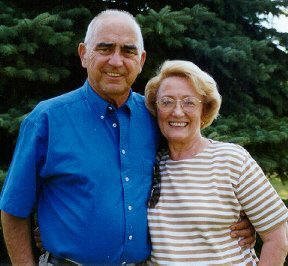

I did remarry, in

1978...... Margot, a native of Frankfurt, Germany - a resident of the

U.S.A. since 1951 . She brought to me two more wonderful grandchildren.

Margot and I have spent many hours talking about the war and how it

affected our lives. We have a common interest in reading about World War

II. Our personal library contains nearly as many books about the war, as

do the local libraries.

Margot, a War

Orphan, suffered many hardships during the war. Bombers buried her for

two days under a shoe store where she worked after school. Her father, a

railroad crewman, was killed on a troop train. Her mother was killed in

their home during a bombing raid.

Margot and I went

back to Germany in 1980. It was my first trip since the war, and her

second. We traveled from Luxembourg up to St Vith, Belgium then east to

Schönberg. We stopped, for a very short time, on the Schönberg-Bleialf

Road, where I was captured. It was near what I thought to be the hill in

the woods where the Germans took me prisoner. It was cold, cloudy and

raining. I had not prepared myself with proper maps. I had not prepared

myself for the psychological impact of returning to the battle area. We

stood on the road for about five minutes. My heart was pounding. I had

to get out of the area.

That evening we

dined at the Gasthaus Zum Dom Stein, a lovely restaurant in Trier,

Germany. During dinner Margot said "John, while we on the road outside

Schönberg, you looked as if you were in a trance. Did it bother you that

much?" It did, for I was remembering the events of December 19, 1944. 1

was trying to recall what the area looked like then. I could see the

soldiers on the battlefield. I could hear them calling for medics. I was

sure I was near the woods where so many were killed. I could visualize

Germans in white snow suits and camouflage. Because of the passing of

time the forest looked different. The trees had grown, hiding the

lightly covered slope I remembered. I was confused, uncertain and could

not understand my emotions. I had to leave. I could not stay. In my

anxiety I forgot to take pictures while standing at the foot of

Linscheid Hill, southeast of Schönberg. Yet, during our three week

journey I took over 600 photos, but none of the village of Schönberg or

the battle area by the woods.

Margot's time for

trauma was to come. We continued our journey down the Mosel River from

Trier to Bernkastel-Kues. Then on to Koblenz, to cross the Rhine using

the same bridge that I walked across on my way to Stalag 12-A, Limburg

an der Lahn, Germany.

From there we

continued to Frankfurt. After checking into the Hotel Intercontinental -

Margot and I visited the area where her home had been bombed. The

outline of the basement of her former home still could be seen - the

house had been razed and cleared from the area in the ensuing years.

Then nearby, to visit a Lutheran Church, the place of her baptism.

Across the street was the rebuilt school she had attended as a young

girl. Behind her school and across a playing field was another large

building. Margot told me that was where Horst, her younger brother, had

attended school.

The next day

we found Horst. Tears still come to my eyes when I think of the reunion

of Margot and Horst. Margot had not seen him for 32 years. We found him

by looking for his name in the

Frankfurt phone directory. They were

separated after the war. They had gone to live with an aunt and Horst

had left them. Margot then married an American soldier and moved to the

United States.

After many attempts, over several years, she had given up in her search

for him. We learned from Horst that he had returned to

Frankfurt several years

after leaving Margot and their aunt.

Margot Mayer Kline and Horst Weimar, her brother, in

Frankfurt,

Germany

in 1980.

Margot had just discovered Horst. She lost track of him in 1945 and had

never been able

to locate him, until our trip together back to

Germany

in 1980.

We visited

with Horst, and his wonderful wife Ericka, then continued our journey

through Germany.

Three weeks after we returned home to

Middleton,

Wisconsin,

Horst came to visit us. He came again in 1981 bringing his wife Erica.

In 1982 Margot went back to

Germany

for three weeks to visit them. Horst took her to the cemetery where

their mother is buried. They then visited their childhood haunts, the

park, the lake where they used to swim and their old neighborhood.

Margot returned to

Germany four

times total in the ensuing years.

Horst died in 1988,

from complications of a heart problem. I am happy that Margot is able to

remember him as a grown man. She can now live with the thought that they

had once again been together as brother and sister.

Some day I am going back to Schönberg. I now have more knowledge of the

area and the battle. I want to visit the Schnee Eifel. Then I want to

take the roads to Halenfeld, Oberlascheid and Radscheid. Most important,

I want to walk through the woods on Linscheid Hill. Maybe I can find

that place in the woods, where I looked over the valley, listening to

the cries of the wounded, the sounds of incoming artillery, and lived

through Hell..........

(Footnote: 1995)

I returned to

Germany

in September 1995 with 14 other 106th Infantry veterans. We met with 45

German veterans from the 18th and 62nd Volksgrenadiers, the two

divisions who surrounded us and took most of us as prisoners. I shall

document that trip and add it to this diary at another date. It was an

enlightening, emotional, fulfilling, journey that opened old wounds and

brought back memories (many vivid). But it helped the healing process. I

went to Schoenberg, traveled the same roads we traveled in 1944. Went in

the forest on the Schnee

Eifel

where we had been in December 1944. Visited

Henri

Chapelle

Cemetery,

Liege

Belgium

where 128 of the 106th Infantry Division soldiers are still buried.

There are nearly 8,000 American graves in that beautiful cemetery. All I

could see, when I looked at those rows and rows of crosses, were young

men in uniform, healthy, vital and a life to live.

Sadly they lay under the ground, as the results of a war that should

have never been...

(Footnote 1999 )

This September 1995 German/American meeting was so successful that we

were invited back in May 1999. The German Bundeswehr Military Reserve,

Gerolstein,

Germany

sponsored the meeting. That organization is similar to our Military

Reserve Units. This time we were a group of 62 people, 32 World War II

veterans with wives and friends. The German contingent of veterans

numbered 32. The healing process continued. 55 years after the war we

now recognize we have gained new friends. Friends who understand what

war is about, who suffered under a dictatorship and a mad ruler. When

you listened to their stories, you could recognize that they also had

suffered greatly in their early life. The results of that war never

leave us. It will be with us until we die. At least now we know what it

was like on the other side of the battle ground. We found that many of

them were younger than us." It is hard to believe," said one German,

with tears in his eyes, "that we each stood up in the

Ardennes

and tried to kill each other."

How true that is 55 years later.....

John Kline

Formerly Sergeant Squad Leader

2nd squad, 1st Platoon,

M Company, 423rd Infantry Regiment

106th Infantry Division, WWII

Email to John Kline

Home Page: http://www.mm.com/user/jpk

Originally transcribed from the 1944 diary in June 1987.Various and

ongoing additions and corrections 1999-2000

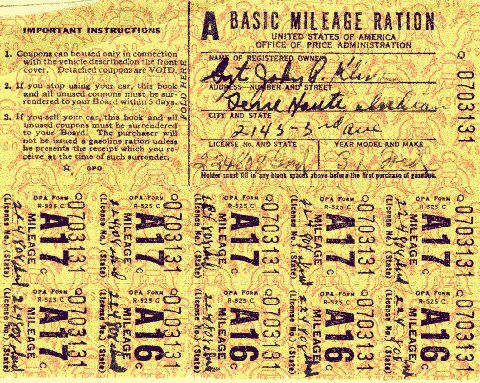

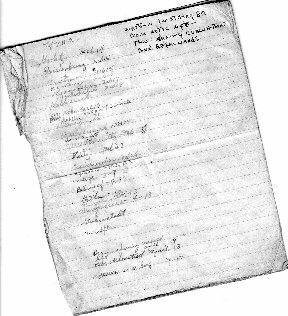

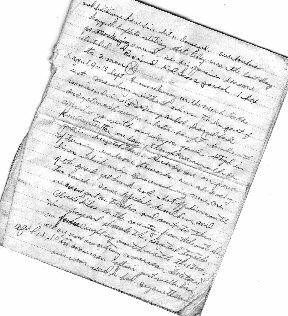

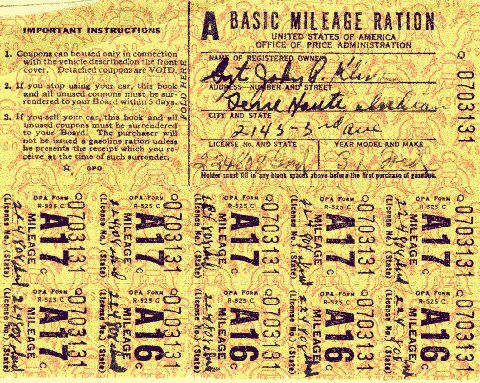

Left: The front page of the original

notebook paper given to me by an English soldier.

Right: Part of the transcript I had penciled in as the opportunity

arose.

I kept these notes hidden under my clothes. I was only searched once and

they were not discovered. All in all, the original

transcript used 15 pages of handwritten "reminder" notes. I amplified on

some of the finer parts when I got back home and my memory was still

sharp. As I gained more knowledge, after getting home, I amplified some

of the writing to be consistent with the reported "happenings" of the

time. Every time I read this diary, it brings back sharp memories of my

experiences. I hope you enjoy reading them (my experiences) and it helps

you understand how a soldier must have felt under these circumstances...

John Kline

From my original

Diary:

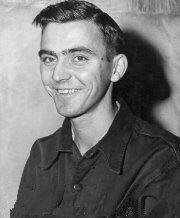

I

was drafted into the United States Army, at the age of 18, one week

after completing my High School education.

Born

January 10, 1925, Glen

Ayre,

Indiana,

(near Terre Haute,

Indiana).

Mother Helen S. Kline, Father Paul H. Kline. My Grandparents/ uncles on

mother's side were coal miners. (German, Welsh, English.)

My father was

orphaned as a teenager, his parents have been hard to trace, but we have

traced them back to

Pennsylvania. He was

raised, as an orphan, in a farming community near Clay City, Indiana.

1943

05/10/43

Induction physical examination

Evansville,

Indiana.

05/17/43

I was inducted into the Army at a

swearing in ceremony at Fort Benjamin Harrison -Indianapolis,

Indiana.

05/43-08/43

Three months of Infantry Basic Training. Company B, Seventh Infantry

Training Battalion Camp Wheeler, GA. Qualified as "Expert Rifleman" with

a score of 193 (the second highest score in the training battalion) on

Toombs

Range,

2 July

1943.

09/30/43

Married Bettie Lue LaFollette, daughter of Milton and Edna LaFollette of

Terre Haute,

Indiana.

(Bettie died September 1977 of Cancer)

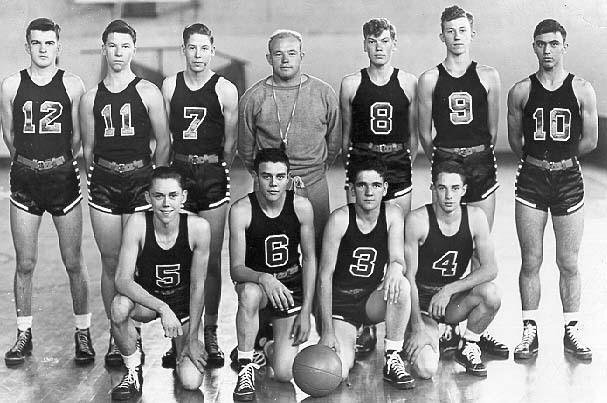

09/43

I was sent to

University of

Alabama,

Tuscaloosa

for Army Specialized Training (ASTP), Civil Engineering.

This was

especially difficult schooling for me, for I graduated from a small high

school Near Terre

Haute,

Indiana

who had a limited curriculum. My best subjects were basketball and

girls. I was not the best "math" student in high school and the pace was

very fast at the level of training presented at this university. I was

honored to have been chosen to attend, but felt that my time was

limited, particularly because of the math section. As it turned out, the

war in Europe

had depleted the human resources and the Army was looking for

replacements to be shipped overseas for D-Day landings. To do this they

drew thousands of men from existing stateside divisions. Along with

many of my fellow students, we were destined to replace some of the men

who were being shipped over as replacements. Our ASTP training was

canceled and the students were sent to various Infantry Divisions

throughout the Continental

United States.

1944

03/28/44

I was transferred to the 106th Infantry Division,

Camp Atterbury,

Indiana.

My first assignment: M Company, 423rd Regiment. Was Jeep driver, 2nd

Squad, 1st Platoon, M Co. was a Heavy Weapons Company, 81 mm mortars and

30 caliber water cooled machine guns.

I learned,

later, that this division had lost over 600 officers and 6,600 enlisted

men to the replacement process. Many of these men were involved in the

D-Day landings in

France

in June 1944. I was amongst the 1,220 ASTP students who had been sent to

the division to replace these trained men. There were also 1,100 Air

Cadets, 1,500 men from other divisions and 2,800 men from miscellaneous

sources such as disbanded military police units, special training

battalions and various service commands. Our commanding general, in a

report after the war, said that all this was fine, since these men were

of high caliber, but the division had one foot on the gangplank. In

other words, a division that had been highly trained now had nearly 50%

of its personnel that had to be trained in the short months from April

1944 to Oct 1944 before we shipped overseas.

05/23/44

Asked for transfer from Motor Pool to Company and was assigned to 2nd

gunner, 2nd squad, 1st Platoon. Sgt Smith was our Squad Leader.

08/08/44

Hospitalized, Camp

Atterbury,

Surgery.

08/21/44

Wife delivered our son, John Theodore.

08/24/44

Released from Wakeman

General

Hospital.

My wife tried to tell how tough the birth of our son was. I tried to

tell her how tough my surgery was on me.

08/24/44

Appointed acting squad leader, 2nd squad, 1st Platoon, M Company. Squad

Leader Sgt. Smith sent to Replacement Depot.

09/06/44

From my Service Mementos:

My Last Will

and Testament

was signed by Pfc John Paul Kline (me) and witnessed at

Camp Atterbury,

Indiana

by Pvt. George R. Claffy,

Chicago: Pfc Gilbert J.

Helwig, Chicago; Pvt Donald A. Palmer,

Detroit.

In 1987, I discovered Gilbert Helwig, having had no

contact with him since the war.

10/04/44

I was promoted to a rank of Corporal.

Wet down stripes (a custom after promotions, you go out and

try do drink up the town) "Wet Down your Stripes"

10/05/44

Appointed Squad Leader

Promoted to Sergeant, 2nd Squad, 1st Platoon

M Company, 423rd Infantry Regiment, 106th Infantry Division

Dominic Damore 1st gunner, Lloyd Breeden 2nd

gunner.

10/09/44

Left Camp Atterbury, by train, early

Monday morning.

10/10/44

Arrived Camp Myles Standish,

near Boston,

Mass.

Staging area for overseas move.

10/16/44

Left

Camp

Myles

Standish. Arrived New York

after dark, boarded Queen Elizabeth, assigned to State Room B-95 with

eight or nine other company members.

10/17/44

We left New York

in the early morning. We did not see Statue of Liberty. The trip was

peaceful. I ate mostly Spam sandwiches and Malo Cups, for I could not

stand the greasy English sausage and potatoes. I would like to bring

wife and family on the Queen after the war. We were told that the

"Queen" was chased by two submarines. I understand that the she

had a record of outrunning fifty subs on one mission.

10/22/44

Arrived at Glasgow,

Scotland,

Firth of Clyde.

This was the only time in crossing the

Atlantic, that we were placed on

alert. We were instructed to stand on the outside deck with our life

belts on. They told us this is standard practice going into a harbor,

where the subs could be lying in wait.

10/24/44

We left Glasgow

by train late evening. Rode all night. Breakfast was coffee, chips and

meat pie on the train.

10/25/44

We arrived at

Cheltenham,

England.

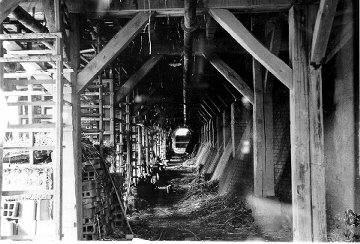

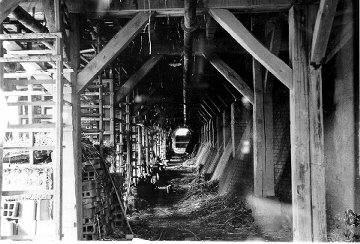

The 423rd Regiment was billeted on the grounds of the Cheltenham Steeple

Chase track about ½ mile from town. My squad was billeted in the press

building atop the main grandstand. The surrounding country side was very

hilly. It was a beautiful area. Before the June invasion of

Normandy,

the track area and grounds had been a very large encampment. There were

countless wooden floors, in row by row formation throughout the grounds.

They were used as floors for the hundreds of squad tents sheltering the

multitude of troops.

We were fortunate

have quarters in the Press Room, atop the Main Grandstand -overlooking

the finish line on the track. Below us in front of the Grandstand

building, was a picturesque recreation building. It was used for

administrative purposes when the track was active. It had a lounge, and

a pool table. We enjoyed it. Some of our troops were

billeted in metal "Quonset" huts, a building that looks like a very

large steel culvert pipe sawed in half, horizontally lying on its side.

The Quonset huts were scattered throughout the area near the

grandstands.

We spent many hours

in training marches, over the hilly countryside, while here. There was

little physical evidence of the war, except the encampment area

mentioned before. There were munitions stored along the roads in

protective bunkers. During one of our many training marches, we came

across the remains of an English bomber, lying scattered across a hill

top. From what we could see, this area had not been damaged by the

German bombers.

Though the

training was tough, we did get a few evening passes into town. To me, as

a country village boy, Cheltenham

was a unique town. It was picturesque as I suppose most English towns

were.

The steeplechase

track was on the edge of town. When we did have a pass we could walk

into the town. Of course, it was always filled with soldiers. There were

a few places to eat, and food was not plentiful. We probably had more

than the local townspeople. I remember going into town for dinner one

evening. After a couple of warm glasses of ale in a Pub, I found a

little restaurant on a side street. It had quaint little embroidered

table clothes. It was relaxing, but the meal was sparse. I don't

remember what I had to eat. I have a great distaste for lamb, so I am

sure it was not that.

Most of our

free evenings were spent walking the streets, having a few beers and

trying to find some familiar face. The town was always "loaded" with

soldiers. Little wonder the British were glad when we all went home.

11/06/44

In a letter to my wife on this date I wrote:

"I went to a double feature movie last night. Calling Dr.

Gillispie and Lend Me Your Ear were playing. I became bored

and returned to quarters to listen to the radio. Charlie McArthy and

Edgar Bergen were being featured. I am listening to the ABC Armed

Services Network. It's sure nice to hear American songs. Bing Crosby

just finished singing Dreaming of a White Christmas. That song

will never get old. We listen to a lot of songs and news from the Armed

Services Network. M Company is on guard detail. I

was lucky and missed out on it. Not much going on this evening. Love

11/09/44

Shown as from "Somewhere"

I don't see how I am going to write tonight. The fellows are playing

cards and arguing about the North and the South. Doesn't make much

difference, we are all Yanks to these people over here. We put our

patches on yesterday, so it won't be long till we can tell where we are.

... Just saw The Song of Bernadette and The White Cliffs of

Dover. Both were good.... Came back to

quarters to play a little Pinochle, I don't play Poker anymore... How is

Teddie (our son) tonight? I haven't received the pictures yet. I sure

would like to see him. I'll bet he is sweet. He

ought to be, look at his Ma and

Pa.

We are into heavy physical training. They [the Armed Forces network] are

playing "Amor" the fourth time today........ Love

11/19/44

Right now I am listening to Glen Miller on the

Armed Services Radio. I went to

Cheltenham last night with

another Sergeant. We ate in a Greek Restaurant. They charged us 5

Shilling for one little hamburger, a few so called French fries and a

cup of coffee. That's a buck. Food here is no comparison to food at

home. They us different seasoning, and the bread is flat. Remember, -

you're the sweetest little gal I ever knew .... Tell Teddie hello for me

and to keep his little chin up. Love Forever.

11/25/44

Another letter sent: Hi Sweet, How's the little

gal. I just received three boxes. I got the fruit cake, candy bars and a

box of caramels. Boy, it sure was nice to receive a box from home. I

even smelled the paper to see if I could smell a little bit of

Indiana.

We have

been very busy lately, Tonight, I am Battalion Charge of Quarters (CQ).

I ate about fifteen minutes early today and the First Sergeant stuck me

with this duty till 0200 tomorrow morning. We took a little trip

yesterday on some detail. Saw a lot of the countryside. The towns over

here are real quaint. The homes and business buildings are all built of

stone. All the streets except the main street are without sidewalks. The

houses extend right out to the edge of the street. I have to admit the

homes over here are very pretty. The countryside is beautiful. The beer

is bitter, and it doesn't take much to set you on your can. Well

Sweetie, better close for now ...... Remember to send me a pair of

one-finger mittens (trigger finger open).

We occasionally were

assigned work details away from camp. I recall traveling through the

country side in the rear of a 4X4 truck, to get supplies from another

base. On another day off, I hitched a ride to an English base nearby and

visited with some of the troops there. There were a lot of Quonset huts,

I spent most of my time in their recreation hall. There was little

difference between the English compound and ours. I did find it

interesting since this was my first visit with troops, other than

American.

We were issued the

new, longer style field jackets with tighter cuffs and a draw string

around the middle. That evening I volunteered to go into a nearby Pub

and bring back some Fish and Chips. Since I did not have a pass, I

sneaked through a hole in the perimeter fence and walked to a nearby

Pub. Fish and Chips are always wrapped in newspaper for carry out.

On the way

back I was caught in a rainstorm. The newspaper containing the fish and

chips was soaked. I stuffed the bundle inside my jacket and made my way

back across the track to our billet. It took a lot of work to get the

grease out of my new field jacket. The Fish and Chips were very good. My

squad applauded my heroics in saving the chips. Then they took a couple

of English pound notes from me in the evening craps.

11/28/44

After a heavy training schedule, we went by train to the

port of

South Hampton

for shipment to

France.

11/29/44

Arrived in South Hampton.

Boarded the Duke of Wellington, a small English craft. It held

only a small number of troops. It was showing its age and had seen a lot

of action. There were ominous signs all about, like "Don't Prime

Grenades" and "Keep Weapons Unloaded." The

English Channel was

very rough. I understand that it is always choppy. I had never been on a

seagoing vessel, other than the "Queen" on our way over here. The

Duke, pounding the waves with its bow, pitched and rolled like a

roller coaster.

We were happy to reach the temporary harbor at

Le Havre. It

is standard practice on entering a harbor area to stand to, on the

outside deck, with life jackets on.

11/30/44

Le Havre,

France.

The original docking facilities had been destroyed during the invasion.

It was now made up of many old ships, cabled together to make the

temporary harbor. We debarked and formed up on the docks. It was still

light.

If you entered the Le Havre

harbor after the invasion, like me, you probably saw the demolished

house on the beach. It had a bathtub hanging out the window. I saw a

picture of it after the war, in Life Magazine.

Le Havre

was leveled to the ground during the invasion. There was little

standing. I remember seeing a few German pillboxes that had been

camouflaged to represent commercial buildings. There was a very heavy

downpour of rain, as we marched nine miles to board trucks late that

night.

12/01/44

Arrived at Field J-40 (a staging area) near

Rouen,

France.

We joined other M Company members who brought along our squad jeeps. We

used our pup tents for sleeping. The weather was wet and miserable. We

could hardly keep the tent stakes in. As a consolation the food was

good. The terrain was flat and open, with a few small woods. It reminded

me of Indiana

farm land. We had little to do. One afternoon, a

couple of us, walked down the road and bought a bottle of wine from a

farmer. He got our money, and we got his bad wine. We went across the

road into some woods, where we found an old wooden building. We finished

our sour wine, and then went back to camp.

We bivouacked

in our two man pup tents for the six days we were at J-40. It rained, at

least once a day. We were never able to get completely dry and

comfortable.

12/07/44

Left J-40 combat loaded with jeep, driver and 1st gunner early morning.

It was getting colder. We had the jeep top up and the side curtains on.

We kept warm by using our new liquid fuel cooking stove. It was a small

stove, enclosed in an aluminum canister about the size of a large

thermos bottle. Some men used a can filled with sand and gasoline to

keep warm. As we traveled along the French road towards

Belgium,

we came across miles and miles of German vehicles that had been strafed

and burned. They were lying in the ditches, either completely burned or

stripped.

12/09/44

As we entered St Vith, Belgium, older, established troops gave us the

normal "new kid on the block" salutations. They yelled at us, "You'll be

sorry" and other similar phrases, some not so nice. We set up bivouac in

woods on the edge of town. The large pines, looking like huge Christmas

trees made the woods quiet, warm and very beautiful. The silence and

peaceful surroundings of the pines and snow, was pleasant. Especially

after the week near

Rouen,

France,

where we had rain beating on the pup tents and the hustle and noise of

the motor march on the way to St. Vith.

12/11/44

We left the woods near St Vith for front line positions. Our destination

was a defense line in the

Ardennes forest atop the Schnee

Eifel (Snow

Mountain).

The positions were 12 miles east of St. Vith and were in

Germany.

A name we would learn to remember, Schönberg, was 9 miles east of

St Vith and 3 miles west of our positions. We were facing the German

troops from emplacements on the East slopes [reverse slopes] of the

German Siegfried Line, known as "The German West Wall."

We took over

positions held by the 2nd Infantry Division and exchanged much of our

new equipment for their old. The exchange was to be made as quickly and

quietly as possible. The 2nd Division was being transferred to

Aachen to

participate in an attack on the Roer Dam area. My machine gun position

was a log bunker with field of fire obstructed by dense forest.

Conditions were quiet. Excellent chow was served twice a day.

Historians and military strategists, argue that the Schnee Eifel

positions should never have been occupied. They say that it was

impossible to launch an offensive from there. They argued that the

positions presented no defense against an assault from the east. This

the Germans proved, on Dec 16, as they cut off our positions by

attacking around the north and south ends of the Schnee Eifel. They, the

crystal gazers, were right. A static defense line was not the answer for

a thinly spread force. Any penetration through our lines would result in

disaster.

M Company, 423rd

Regiment, was assigned positions along the front line to support the

rifle companies. An Infantry heavy weapons company, like ours, is

equipped with 81 mm mortars and water cooled 30 caliber machine guns. A

rifle company, is equipped with automatic weapons and mortars that are

only 60 mm mortars and air cooled machine guns. Our duty was to support

the various rifle companies of the 3rd Battalion, 423rd Regiment. They

were, I, K and L Companies. Such was our deployment along the tree

covered ridge atop the Schnee Eifel.

The

Ardennes forest is, for

the most part, heavily wooded. It is interlaced with many small logging

trails, fire fighting lanes and streams. We slept in rough, but warm

dugouts and enjoyed solid gun bunkers. Built by the 2nd Division, they

were built of logs, with a log and earth roof.

We completed our

changeover with the 2nd Infantry Division as darkness came. We had no

time to become acquainted with the territory around our new positions.

Because of that, and since we were new and inexperienced troops, our

first night was unforgettable. We were facing, for the first time, an

enemy that we only knew from newsreels and training films. It was a

sleepless and anxiety filled night.

I can personally

confirm that a snow covered tree stump will actually move. That is, if

you stare at it long enough - and if you are a young, nineteen year old

machine gun squad leader peering, into the darkness, towards the enemy

through a slit in a machine gun bunker. Every sound was amplified. Every

bush could be an enemy crawling towards you. Your eyes grow bleary from

staring into the darkness. You are happy when the relieve crew shows up.

The next day, you take a good long look at the stump that moved during

the night. You take note of all unusual objects, and then things start

to settle down.

There were two gun

emplacements (bunkers) for my machine gun squad. One was higher on the

hill, and the other a couple of hundred yards down the slope. When we

first moved in, our gun position was in the lower bunker. After the

first night we were asked to move back up the slope, to the alternate

bunker. For what reason, I don't know. We did appreciate the move, for

the alternate bunker was much warmer and drier. As in the lower bunker,

there were "trip lines" running from the bunker down into the forest and

through the barbed wire. The lines were attached to hand grenades and

flares. Then, they were placed in their shipping containers and

attached to tree trunks. If we detected movement in the area beyond the

barbed wire we could pull a trip line. This would cause a grenade to

explode, after it was pulled from its container. A flare could be

ignited to light up the area in the same manner. Our field of fire was

good, but very limited. The 2nd Division had cut down a lot of trees and

cleaned out the brush. However, the forest still offered the enemy

excellent cover.

I remember one day

being convinced that I could see a vehicle, in the woods, several

hundred yards down the hill. The contours of the hill and the thick

forest were playing games with my imagination. When I looked at it from

another vantage point, the illusion disappeared.

There was one

rifleman to the left of my bunker. He was entrenched in a log covered

foxhole. According to members of the patrols, this rifleman was the last

person between my machine gun emplacement and the 422nd Regiment. The

422nd Regiment was reported to be several hundred yards north on the

Eifel.

The two regiments sent alternate patrols across the unoccupied space

each half hour. They reported very little German activity. The first

days passed without incident. The most excitement we had in my bunker

area was when a nearby 50 caliber machine gun started blasting away. The

gunner had become bored and decided to kill a deer.

We left the bunker

area twice daily to eat our meals in a mess tent. It was back of us, to

the West, on the opposite side of the hill. To get to it we had to walk

along a trail, through a clearing, and down the other side. The Germans

had the clearing zeroed in. As we crossed the clearing, we had to be

prepared to hit the ground in case they decided to harass us. The 2nd

Division's squad leader that I relieved, said two men had been killed

crossing the clearing a few days ago. Our daily trips to the mess tent

were something to look forward too. The food was good and the Mess

Sergeant seemed to be friendlier since we have moved up to the front

lines. I did enjoy those meals, there were generous portions and we

could chat with the others and get brought up to date on the local news.

12/16/44--12/17/44

History shows -- The Battle of the Bulge" started

at 0530 on the morning of

December 16, 1944.

Because we were high atop the Schnee Eifel and out of the mainstream of

the German Offensive, we were probably the last to know that it had been

launched. I cannot remember any evidence or any sounds that would have

indicated to us the size of the battle that was to take place. A battle,

that was to become known as one of the largest battles in the history of

World War II. The 40 days that battle raged were the coldest and

snowiest weather remembered in the

Ardennes

Forest

area. More than one million men, 600,000 Americans and 500,000 Germans

and 55,000 Englishmen fought in this battle. 32 American, 3 British and

29 German Divisions were in the battle before it ended. The Germans

suffered 100,000 killed, wounded or captured. There were over 81,000

American casualties, including 23,554 captured and 19,000 killed. The

British suffered 1,400 casualties and 200 killed. Each side lost 800

tanks and the Germans lost 1,000 aircraft. The Malmedy Massacre where

nearly 90 American Soldiers were slaughtered was the worst atrocity,

against the Americans, during the European Campaign.

My division, the 106th Infantry Division, suffered over

416 killed in action, 1,246 wounded and 7,001 men missing, in action in

the first days of the Battle

of the Bulge.. Most of these casualties occurred within the first three

days of battle when two of the three regiments were forced to surrender.

In all, there were 641 "Killed in Action" from our division through to

the end of the fighting. In losses - the German Ardennes Offensive,

later to become known as "The Battle of the Bulge," was the worst battle

for the Americans in World War II.

Our company commander set up his headquarters in one of

the enormous Siegfried Line bunkers. The bunker was not completely

demolished, as they usually were. The underground rooms were intact and

accessible. He had taken a room several flights down. The command bunker

was on a crest of a hill. The firing apertures faced west towards

Belgium,

the backside towards the present German lines. There were steep slopes

on either side, with signs and white caution tape warning of "Mine

Fields." There was a pistol belt and canteen hanging in one of the trees

on the slope. Apparently, some GI had wandered into the mine field.

German activity was

reported along our front on the 17th (remember the Bulge started on

the 16th). The commander called me back to the command post. He

informed me that I should be prepared to move my gun to his area to

protect the command post. While visiting with him, I noticed that he was

very nervous. His 45 Colt pistol was on the table, ready for action. Our

Master Sergeant, who was also present, seemed equally concerned. Later I

was to learn the reason for their anxiety. I suspect, in retrospect,

that they had been made aware of the German breakthrough, yet did not

yet know the importance of the news.

While in the

vicinity of the command post bunker, I watched a U.S. Army Air Corps

P-47 Thunderbolt chase a German Messerschmitt (ME 109) through the sky.

They passed directly in front of us. Our area being one of the highest

on the Schnee Eifel, gave us a clear view of the surrounding valleys.

The P-47 was about two hundred yards behind the ME-109 and was pouring

machine gun fire into the German plane. They left our sight as they

passed over the edge of the forest. We were told later, that the P-47

downed the German ME-109 in the valley.

As it turned out, my

machine gun was not moved to the command post. During the night of the

17th we heard gunfire, small arms, mortars and artillery. We also could

hear and see German rocket fire to the South. The German rocket launcher

was five barreled and of large caliber. The rocket launcher is called a

"Nebelwerfer." Due to their design, the rockets make a screaming sound

as they fly through the air. Using high explosives, but not very

accurate, they can be demoralizing if you are in their path of flight.

12/18/44

On the morning of the 18th I was instructed to report to the mess tent

for a briefing. As I was walking to the tent I noticed two German

prisoners being guarded by an American GI. They were setting under a

tree near the mess tent.

During the briefing

we were told that the Germans had broken through our supply lines. This

rumor turned out to be true. However, we were not informed of how grave

the situation was. The facts were, as you will read later, that we were

cut off from the rest of the division early in the morning of the 17th.

The artillery and rockets that we had heard to the south, were sounds of

the battle that was taking place at Bleialf, a small village on the road

between Prüm and Schönberg. The 423rd Anti-Tank Company who had that

defensive area had been thrown out of Bleialf on the 16th. They used all

available troops in the area and pushed the Germans back out of Bleialf,

only to be overrun again on the morning of the 17th. They were

overpowered by the tremendous numbers of German troops heading northwest

up the Bleialf-Schönberg road. The Germans had closed the pincers behind

us, at Schönberg. We were like a boulder protruding from the middle of a

stream. This proved the military strategists to be correct. A mountain

is not the place to be when you have no support.

But, I

am getting ahead of my story....

We were told to eat a big breakfast because

we were going to hit the road. We were ordered to head west and join

with the rest of Regiment. We, presumably, were to make our way to St.

Vith. The cook made stacks and stacks of pancakes. We all ate like it

was our last meal. Little did we know that this would be our last decent

meal for the next four months. We then prepared to leave our positions

taking only the bare necessities and as much ammunition as possible.

Our personal gear was in our duffel bags, stacked near the mess tent. We

left them there, thinking that we would retrieve them later. I had an

old Kodak Autographic camera in my duffel bag. It had been given to me

as a gift by a high school classmate. I always regretted the loss of

that camera. One of my active hobbies after the war was "photography."

We left our

Schnee Eifel positions, heading west towards Schönberg. I was in my

squad jeep, with my driver and gunner. We were traveling between columns

of troops that were afoot. At that time I was not familiar with the

names of the villages or towns in the vicinity. In my studies after the

war I read that we evacuated from the Schnee Eifel positions west

through Halenfeld. Then we took a right fork at Oberlascheid to

Skyline Drive.

Then near Radscheid we made a left then a right (northwest) onto a

logging road leading into the woods overlooking Schönberg.

(This special note was added during the

update of this diary in March 1993.) In 1987, I read a book written in

1985, A Time for Trumpets, by Charles B. MacDonald. He had written

another book just after the war, Company Commander, which was about his

infantry company that fought in the Bulge. He was the youngest company

commander in the European Theater of Operations in World War II. He had

spent five years prior to publication researching the battle, traveling

to the area and gaining information from many of the participants.

His book

explained in more detail what happened during the

Battle of

the Bulge and seemed to be written from the ordinary soldier's

viewpoint. For whatever reason, this book turned me on. I began to think

back, my mind searching for details of my personal experiences, and at

the same time trying to remember the names of my buddies, who I seemed

to have pushed out of my mind for all these years.

Eventually,

from April 1987 to this date, March 1993, I have located or accounted

for 77 of my former buddies from "M" Company. Of this number 10 have

passed away. One of those that I contacted early in my search - 1987 -

was Colonel C.C. Cavender, the Regimental Commander of the 423rd Combat

Infantry Regiment, of which "M" Company was a part of. I was privileged

to have the Colonel as my roommate at the 106th Infantry Division

Association's 1990 Annual Reunion in

Sacramento,

California.

At that time the Colonel was 92 years of age. We spent hours talking

about his and the 423rd's part in the

Battle of

the Bulge........

Colonel C. C.

Cavender told me that we, the 3rd Battalion of the 423rd Regiment were

attempting to get to Radscheid to assist the 2nd Battalion of the 423rd

Regiment. They were engaged in a fire-fight along the Bleialf-Schönberg

road during their attempt to cut the road which had been taken by the

Germans. He told me that originally the two regiments were to march

south of Schönberg and make their way back to St Vith to join the rest

of the division in a defense situation. Instead of assisting the 2nd

Battalion Colonel Cavender received orders to move the 3rd battalion to

the right of the 2nd battalion and head it toward Schönberg. The route

was to be through the hilly woods, later identified as "Linscheid Hill"

southeast of Schönberg,

Belgium.

According to orders, we were to cause utmost damage to the German troops

there and continue to St. Vith.

Colonel Cavender,

after the war, received much criticism for moving the 3rd battalion to

the right around Puett. In a recent conversation, October 1989, with

him, he said, "Those were the orders I received from General Jones." He

then told me more about the battle at Bleialf. He formed a provisional

battalion, the 423rd Anti-Tank Company plus a mixture of men from other

units. This provisional battalion threw the Germans back on the 16th,

only to be thrown overrun again on the 17th. After moving into the

Schnee Eifel front line positions he, Colonel Cavender, inspected the

whole area, including the area around Bleialf.

Accompanying him was

his counterpart, Colonel Boos, the 2nd Division's Regimental Commander.

Colonel Cavender expressed concern to him, to about the open corridor

from Prüm to Schönberg. It was defended by a thin line of troops. He was

concerned, as had been his 2nd Division counterpart that, in case of an

attack there was a lack of secondary defense. His fears turned out to be

true. He asked Colonel Boos what reserve or "backup" resources were

available and Colonel Boos replied, "None."

When the Ardennes

Offensive broke, the Germans poured around the Schnee Eifel from the

South, through the Prüm Corridor. They then closed the pincers by

joining with the Germans coming into Schönberg from the North along the

Andler-Schönberg road.

In November of

1989 Colonel Cavender sent me two packets of his personal papers. These

are mostly personal letters from 423rd Regiment friends and from a few

of the division officers. He had to explain, after the war, his reasons

for his strategy during the first three days of the Bulge, and also

explain the reason he surrendered his regiment on

19 December 1944. I have

read and reread these papers, many which relate to what happened during

that period. I can confirm that those facts I mentioned above are the

same as his written notes and papers and his conversations with me on

the telephone since 1987 as well as our personal visits in 1990 at the

reunion in Sacramento.

It seems, at least

to me and some of my buddies, that the Prüm Corridor, the area that the

423rd Anti-Tank Company was defending and the Losheim Gap, the area that

the 14th Cavalry was defending, were left open for a purpose. Could that

be true? Were we part of a calculated risk, or were we setup? It looks

as if we will never know. (After much study, after the war and into

1999, I do not believe we were "Set Up." I simply think that our Army

and Corps Commanders were over confident that the war was about to end.

I, personally,

can relate what we were told as we left the Schnee Eifel to march to the

rear towards Schönberg

Belgium

(about three miles to the West). There we were to meet a combat team of

an armored division in

Schönberg,

Belgium.

Later, after getting underway, we were informed that the Germans had

encircled us, and that we had orders to fight our way through Schönberg

and try to reach St. Vith. In fact, the Germans did occupy Schönberg,

the promised armor was not there.

After the war

I learned that on

the 16th of December 1944,

part of the German 18th Volksgrenadier Division and the Fifth Panzer

Army's Fuhrer Begleit Brigade [Tank Brigade] broke through the 14th

Cavalry Group, who were on the left flank of our division (north of us

on the north edge of the Schnee Eifel). The Germans drove through along

the Andler-Schönberg road. They were in Schönberg on the 17th. We did

not leave the Schnee Eifel until

the 18th of December, 1944.

The 423rd Regiment's

Anti-Tank company at Bleialf, on the South edge of the Schnee Eifel, had

been overrun on the 16th by troops from the German 18th Volksgrenadier

Division. A miscellaneous group of troops, including the remains of the

Anti-Tank company had recaptured it. Then on the 17th the 18th

Volksgrenadiers made a final plunge and once again broke through

Bleialf. They were pushing towards Schönberg, a few miles to the

Northwest. We were to see them hit our backside during the night of the

18th and 19th as we overlooked Schönberg from Linscheid Hill southeast

of the town.

Both German

units, those from the North down the Andler-Schönberg road and the ones

on the South on the Prüm-Schönberg road had converged on Schönberg. They

had closed the pincers. By that action the 422nd Regiment, and my

regiment, 423rd Regiment of the 106th Infantry Division were trapped in

the Ardennes

forest southeast of Schönberg. Considering that, Captain Hardy, my

company commander had reason to be nervous when they talked to me on the

17th, as he explained that I was to bring my gun crew back to his

Command Post to guard it. He must have been aware of the seriousness of

the situation as it developed, but did not reveal that to any of our

personnel that I can learn. Whether he was aware or not will never be

learned. He was killed on the morning of the 19th, when the battle

opened up on the Schönberg Hill.

German units

involved in the battle:

The 18th Volksgrenadier Division was formed in

Denmark

around the cadre of a Luftwaffe field division, with fill-ins from the

Navy. It was at full strength [17,000 men] and had two months

experience, in defensive positions in the

Eifel area. [The 106th

Division was not at full strength. They probably were at less than

12,000 men. They had 5 days experience on the front line].

The Fuhrer Begleit Brigade, under control of General der Panzergruppen

Hasso von Manteuffel, was built around a cadre of troops from Hitler's

headquarters guard. It included a tank battalion from the Gross

Deutschland Panzer Division (still on the Eastern Front). It was

strongly reinforced with assault guns [large caliber guns mounted on

tracks]. They were equipped with 88mm and 105mm pieces from the 460th

Heavy Artillery Battalion.

It should also be noted that even though there were many young German

troops and some fillers from other branches of service, the German unit

commanders were veterans. The 106th Division commanders were, with a

couple of exceptions, facing the enemy for the first time. The complete

surprise of the attack, the overwhelming numbers of German troops and

the static position of our two regiments atop the Schnee Eifel

eventually led to our defeat and capture.

12/18/44

Our column did not come under fire until we were near our destination, a

heavily wooded area (Hill 504) southeast of Schönberg. As we approached

the logging trail, near Radscheid, we were shelled by German 88's. My

driver drove the jeep into the ditch on the right side of the road. A

bazooka-man had hitched a ride on the jeep over the right rear wheel. As

we hit the ditch, his weapon fell apart. The rocket fell out and landed

in the mud along side of me, where I had fallen. Fortunately the bazooka

rocket did not arm itself. As I picked myself up, I noticed a pair of

German binoculars lying in the ditch. I picked them up and hung them

around my neck. They were probably left there by German troops who had

been patrolling in this area. I have often thought, "What if they had

been booby trapped?"

A point where

my memory fails is that I cannot remember what happened during the night

of December 18. It would have been logical to set up defensive positions

and sleep in shifts, which we probably did. However, my mind is

completely blank about the events of that night. M Company men I have

met in recent years, 1988 and 1989, tell me that we spent most of the

night trying to get our jeeps out of the mud. The number of vehicles on

the road and an unusually warm spell caused the fields to be very muddy.

The weather turned much colder and stayed that way until after the end

of January.

12/19/44

Battle

positions: In early morning of the 19th I received orders to position my

30 cal water cooled machine gun in the edge of the woods overlooking

Schönberg. I was high on a hill, several hundred yards from Schönberg

overlooking a slope leading into a valley. I could see the house tops of

Schönberg.

Company M, 423rd

Regiment, my unit, was assigned to support L Company, a rifle company,

who were preparing to enter Schönberg. They were advancing down the

slope, attempting to enter Schönberg along the Bleialf-Schönberg road

which was several hundred yards in front of my gun position, in the edge

of the woods. The town and area was infested with Germans, but from my

position I saw no sign of them. I saw little, except the roof tops of

Schönberg ahead of us, and a few of our troops on the slope below us.

A rifle company to

our rear, I Company 423rd Regiment, was waiting on orders to proceed

down the hill in support L Company. It was about 0900 when we were

suddenly hit by very heavy artillery fire. It seemed that all hell had

broken loose. The shells were exploding all around us, on the ground and

in the trees. Men were screaming for Medics. I heard during the day that

M Company's Commander, Captain Hardy, had been killed and the Executive

Officer, Captain Wiegers was blinded by a tree burst. There was a

terrible lot of confusion at that time. I thought to myself that the

officers could be from one of the rifle companies. That was not so, it

was our officers that were hit by tree bursts.

Captain James Hardy, M Company Commander, was killed by the very first

tree burst as the German shells landed in the woods around us. Captain

Wiegers, M Company Executive Officer, although hit, was not blinded. I

learned in 1988 that he rode a tank out of the officer's camp, Oflag

13C, Hammelburg, during an attempted break-out. "Read the book about

Patton's raid on the Hammelburg Oflag, where he tried to rescue his

son-in-law". The name of the book is Raid. Hammelburg was about

80 miles behind the then existing front lines.

Most of our officers ended up being held at Oflag XIII-C

(13C). After the aborted attempt by Patton to liberate the camp, the

Germans put all the officers on the road, marching in the direction of

Bavaria.

Colonel Cavender, 423rd Regimental commander, was wounded on that march.

He and others were caught in the target zone of hundreds of bombers.

Cavender spent several months in the hospital as a result of his leg

wounds. It was during that time that he issued his 423rd Regimental

Order #51 awarding all of us the COMBAT INFANTRY BADGE.

During the day,

19 December 1944, Smitty,

my gunner was injured in the leg by an artillery shell. I was hit on the

backside of my right boot on the same burst. My right overshoe and

combat boot were ripped. I sustained a small wound in the area of the

right Achilles tendon. (In the excitement and trauma that followed, I

did not realize I had been hit.) It was not serious enough to prevent me

from walking and eventually healed. I learned later, in 1987, that

Smitty had his leg amputated in a German hospital and had also suffered

stomach wounds. His stomach wounds caused him to be unable to continue

to work after 1963. He is one of the first men I discovered in 1987,

after reading MacDonald's book that I mentioned earlier.

The first hostile

artillery barrage, at 0900, was unbelievable in its magnitude. It seemed

that every square yard of ground was being covered. The initial barrage

slackened after forty-five minutes or an hour. I could hear the men from

K & L Companies, on the slopes below, screaming for medics. Shortly

after that the shelling started again. The woods were being raked

throughout the day by a constant barrage of small arms and artillery

fire. We were pinned down in the edge of the woods and could not move. I

found some protection in a small trench, by a tree, as the shelling

started. It must have been scooped out by one of the riflemen the night

before. The front of the trench, pointing towards Schönberg, was deeper

than the back. My feet stuck up above the ground. I suppose that was the

reason I suffered a leg wound. At one point during the shelling, I heard

a piece of metal hit the ground. It was a large jagged, hot, smoking

piece of shrapnel, about eighteen inches long and four inches wide. It

landed a foot or two from my head. After it cooled off I reached out and

picked it up. I don't think it was a mortar or an 88mm shell. It might

have been flak from an antiaircraft shell.

I read in 1987, in

MacDonald's book, that the Germans had many antiaircraft guns (88s and

128s) with them during their Ardennes Offensive. They were for

protection in case the weather turned better. They knew for sure that

the Allied air support would eventually come. The German antiaircraft

gun is capable of being used to support ground troops. This is done by

elevating the guns downward, and firing timed bursts or tree bursts into

the trees that explode on contact. There is very little protection as

the fragments rain down from above.

They also had 20mm

antiaircraft guns, mounted on quad mounts and half-tracks. They were

fired into the tree tops, and sometimes at point blank range, causing

severe damage to our troops. The tree bursts, exploding high in the

trees, were hard to hide from. They caused many casualties. There is no

doubt that they were used to our disadvantage.

The weather was overcast and foggy and did not turn to

the better until December 21st or 22nd. The sky cleared and it got much

colder, as we were then walking, as prisoners, back into

Germany.

When the weather did clear, the Germans had the opportunity to use those

antiaircraft guns for their intended purpose, for there was much Allied

air activity. There is no doubt that it was their fortune in having

their antiaircraft battalions near Schönberg, as we approached it from

the East. Those guns were a decisive factor in the outcome of the battle

for that city.

We

had very little artillery support. I learned after the war that the

423rd's artillery support, the 590th Field Artillery to the rear, was

overrun by the Germans troops that were fighting westward towards

Schönberg along the Bleialf-Schönberg road. They fought as "Infantrymen"

but as they learned after the war, were not eligible for the "Combat

Infantry Badge."

On the Schönberg

Hill, rifle companies, mortar and machine gun squads were being pinned

down in the woods. In the confusion, caused by the demoralizing

artillery fire, they were being separated from each other. The 422nd and

423rd Regiments lost track of each other. The day was going bad. There

were no targets in view, at least from my point of view. The Germans

were waiting for their artillery to neutralize us, before they moved.

With the ravaging artillery fire, and no chance of counter artillery, we

were literally sitting ducks. There was some action on the edges of the

perimeter. From my position I could see two German tanks. They were

scouting around the area, in the edge of the woods near Schönberg. One

of them threw out a smoke grenade. I was not able to identify any German

infantry troops, prior to being captured. I learned later that the tanks

I saw were mopping up troops that were pinned down in the fields and

road below. Most of the action occurred early in the fight, between the

rifle companies below us and the Germans across the road.

K & L Companies, in

trying to push into Schönberg, were caught in the ditches and fields. It

was their men that I could see and that I could hear screaming for help.

They were being ripped to pieces by the tremendous artillery barrages.

Unfortunately, my machine-gun was placed too far back of the infantry

company as they attempted to get into Schönberg. Normally, we would have

moved forward, but the same artillery that was destroying L Company was

also hitting us. At the same time German troops coming up the road from

Bleialf were hitting us from the rear. This trapped the reserve company

(I Company) who were preparing to come forward to assist K & L

Companies.

In 1987 I

acquired a list of the 106th Division members belonging to "The Veterans

of the Battle

of the Bulge. I called one of the listed men, Harold Gene Songer of

Danville,

Illinois.

(6/4/87)

He, was a member of I Company, 423rd Infantry Regiment. He said, "Yes, I

was in the woods. I don't know exactly where. "

He said, "I"

Company was being slaughtered. A sniper was killing a lot of them. We

had spotted the sniper, nearby, in a clump of bushes. The range was too

short for the elevating mechanism. My squad leader (mortars) was trying

to elevate the mortar, by holding it vertically. He was killed by a

bullet in the temple. Another mortar man and I grabbed the mortar and

dropped three shells in the area of the sniper, killing him." Songer,

like myself, was captured. He ended up at Stalag IV-A, Hohenstein, near

Dresden.

From Norman

Gruenzner's Postal History of American POWs:

World War II,

Korea,

Vietnam

[State College,

Penn.:

American Philatelic Society, 1979]. Stalag IV-A was located close to

Hohenstein, near Dresden.

The American camp population in December 1944 was 300. In February 1945

it reached 2,217. There were several work detachments, living in a

variety of places. One group lived in

Dresden.

There were eleven British work detachments, but only three or four

American work groups. The camp was closed in March 1945.

Songer asked,

" Were you in the prison train that was bombed on Christmas Eve?" My

answer, "No, I was in a small barracks in Dockweiler, east of

Gerolstein, on Christmas Eve. We were not put into box-cars until 30

December, at Limburg."

That story follows.

The German troops

advancing from the Southeast, along the Bleialf- Schönberg road were the

ones who took over our artillery battalion.

I remember

throughout all the shelling watching a Tech Sergeant, I thought from one

of our mortar platoons, walking and running through the woods giving

orders. He was trying to get troops moving. The mortar, antiaircraft and

artillery fire was fierce. Trees flying through the air, shell were

bursting every where. I hope he made it. He was a very brave soldier,

but was exposed to fierce, ravaging artillery fire.

At one point,

as I looked to the right along the edge of the woods, I saw six or eight

ground bursts, probably 88's. They hit in a small area along the tree

line where several soldiers were trying to find protection. One of those

men was hurled through the air and his body was wrapped around a tree

trunk several feet off the ground. There were continuous cries from the

wounded screaming for Medics. The woods and open areas on the slope

leading to the road, was littered with dead and wounded. Some time

between 1600 (4

p.m.) and 1630 (4:30

p.m.), an American officer, accompanied

by a German officer told us we were surrounded. He told us that we were

cut off from the other battalion, the 422nd, and that our Regimental

Commander, Colonel C. C. Cavender, was ordering us to surrender.

As the history of

this battle shows, we were surrounded on all sides by German troops.

They were heavily armed, with many mortars, antiaircraft guns, assault

guns and artillery pieces. They were being reinforced by more and more

troops from the Southeast and there would have been no possibility of

reversing the battle situation. We disabled our weapons by breaking them

on tree trunks or by taking them apart and throwing the parts in

different directions. After that the Germans led us to a clearing in the

forest and directed us to throw down our equipment. E.g.: ammo belts,

packs, hand-grenades and trench-knifes. I quickly disposed of the German

binoculars that I had found earlier.

We were lead in a

small column down to the Schönberg-Bleialf road in front of the rifle

companies. There were Germans on one side of the road and Americans on

the other. They had been facing each other, in a fierce fire fight, from

ditch to ditch. There were many dead, both Americans and Germans. The

wounded were still crying for help. As we approached the Schönberg road,

it seemed that hundreds of Germans rose up out of the field.

There was a German

truck burning in the middle of the road. Behind the truck was an

American infantryman lying in the middle of the road. He was dressed

like an officer, but with no insignia, as would be normal in combat. His

was wearing his winter uniform, a heavy winter coat, ammo belt and

canteen. He was lying on his back, as if he were resting. The body had

no head or neck. It was as if somebody had sliced it off with a surgical

instrument, leaving no sign of blood. All my life I have had flash backs

of that scene and I still find it hard to believe. I always wonder how

it happened. He was the only soldier, either American or German that I

saw laying on the road. There were many wounded and dead in the ditches

and fields as we were led out of the woods.

The Germans then

walked us in columns to Bleialf (recorded in my diary as "St. Beliath)

where they herded us into a church court yard. I probably recorded the

church name by mistake. It had turned dark and the temperature was

dropping. Most of us were without overcoats. We had only our field

jackets and our winter issue of "Olive Drab" uniforms with long johns. I

recall that I wore two pair of pants, my long johns and my field jacket.

We had to sleep on the ground. I remember how nervous I was. Every

little sound was amplified. I wondered what was going to happen to us

when day break came. We had nothing to eat since early morning, December

18th. (remember - the pancakes).

Captured

19 December, 1944

- Marched 110 miles to Stalag XII-A,

Limburg,

Germany

12/20/44

Left Bleialf at

6:30 AM, we were on the road until 2300

that night. We had no water or food except for the snow from the ground.

During the march, as we were going through a very small village, the

Germans stopped us in front of some civilians. They made us take off our

overshoes and give them to the civilians. That was when I discovered

that my right overshoe had been ripped open on the backside by shrapnel.

The shrapnel had cut through my backside of my rubber overshoe, leather

combat boot and heavy sock. It had then cut around, but not through my

Achilles tendon. It was a small wound, but had it gone any deeper it

would have cut my tendon and I would have been unable to walk.

There was much

evidence, in the area, that a large scale battle had taken place. I

remember as we were leaving Bleialf walking through a small village. It

could have been outskirts of Bleialf, or some small village nearby.

There were German troops in American jeeps. They were opening ration

boxes and meat cans. They were eating our Christmas dinner. My guess is

that this had been our battalion supply depot. As we walked through the

area, I was surprised to see my jeep with four Germans in it. I was

positive it was mine. I had personally painted my son's name, "Teddie"

on the jeep, and the name was there. There had been had been a real

shoot out, with hand to hand fighting. There were dead Americans and

Germans lying in doors, ditches and hanging out of windows. The

infighting must have been fierce, for some of the bodies were on top of

each other.

As we left the town

and just before we made a slight right turn that led us into the

country, I saw a two story stone building. Its upper floor was occupied

by several young women, who waved at us through the open windows as we

went by. I have often wondered if they were brought along by the

Germans. The road we were on eventually took us through Prüm, Germany,

the town that I could see from our positions on the Schnee Eifel. We

ended up that evening sleeping in an open field near Gerolstein,

Germany.

12/21/44

At Gerolstein we were awakened at 0600, and given our first food since

breakfast on Dec 18th. They fed us hard crackers and cheese. Seven men

to one can of cheese. We left Gerolstein during the evening.

12/21/44

Arrived in Dockweiler Dries 2300. Billeted in an old German barracks.

During the three and one-half days there, we were fed one ration of very

weak potato stew. We received two bread rations of one loaf split