|

Robert Jeters |

|

As soon as I turned 18 in September, 1943, I was drafted and then inducted into the Army in November and was sent to Camp Roberts, California for my seventeen weeks of basic training, in Company D, 80th Infantry Division.

Upon completion, I was given a delay in route – ten days at home and my orders called for me to go to Fort Ord, California (Monterrey) where I underwent extensive amphibious training. When all of a sudden we were informed that quite a few of us were to pack our duffel bags and get ready to move out. I thought we were going to the Pacific Theater, but as it turned out, we boarded a train for a long ride to Camp Butler, North Carolina, where we started hedgerow training. We were then sent to Camp Atterbury, Indiana, where we were split up and assigned to various units. With the exception of me and Creech and a guy by the name of Fairchild, we were the only ones assigned to Company C, 424th Regiment, 106th Infantry Division. We had trained together from Day One at Camp Roberts. I was a BAR man and Creech was my ammo bearer. We were only at Camp Atterbury for a couple of weeks before we were shipped to Camp Myles Standish, Massachusetts.

Only there for a while and then to New York where we boarded the Aquitania and sailed to the Firth of Clyde, Scotland. Then a long train ride to Banbury, England. Some more hedgerow training and then across the Channel to La Harve, France, where we unloaded and assembled into a very large muddy field. It was raining cats and dogs. We finally boarded some trucks for our journey through France, Belgium and Germany where we relieved the 2nd Division.

I suppose the point I am trying to make is that I never really had a chance to ge acquainted with very many guys in the outfit. Everything was happening so fast, in fact, at one moment I could not tell you what platoon I was in. All I know for sure is that our Commanding Officer was Captain Miller. I think our Platoon Leader was a Lt. Nelson.

On to December 16th, 1944 –

We were standing in the chow line as the kitchen trucks had just rolled up and was getting ready to serve. I had been standing there gazing up at a mountain that was to the rear of the two-story house we were billeted in. I noticed a railway track up there and where it disappeared into a tunnel in the side of the mountain, thinking that would be a good place to be – inside the tunnel, in case we were ever in an artillery attack.

Then all of a sudden we were to drop everything, get our combat gear and ammo and load up on some 1 ˝ ton trucks that had just drove up. It didn’t take long for us to figure out that something was up for sure. In just a short time we came to a town that looked like it had been shelled before. The trucks stopped right in the middle of a junction with another road, in fact, it looked like we were in the middle of the town, which I later learned was Winterspelt, Germany.

We started unloading when all Hell broke loose – artillery shells exploding everywhere. Creech and I dove into the first shell crater we came too. There were men screaming everywhere for an Aid Man. This was undoubtedly the most horrible, helpless and terrifying feeling that I have ever experienced – nothing to shoot at – just lay there and hope and pray one did not get you. The German artillery had certainly zeroed in on this town. I thought would never end. I have no idea how long it lasted, but it seemed like an eternity. But it finally stopped. I don’t know how many en had been hit in that immediate area, but there were trucks, ambulances, and jeeps everywhere in the town and people trying to attend to the wounded.

We were ordered to move out of the area and assemble down the main road that connected with the road we had come in on. I call it the main road because it looked like it was paved sort of like our blacktop roads in the States. We were ordered to spread out in single file on the left side of the road and move out heading toward the direction that the artillery had come from. As we got strung out and started marching, Creech and I were toward the rear of the column. I was looking up ahead to see how many men we had and as far as I could tell, we had less than a platoon, maybe 20-25.

We were keeping off the road in a ditch and it was lined with a single row of trees and as you looked to the left, there was nothing but a large bare field with some snow covering it, but we could see some very thin forests on up ahead on a ridge. We were going uphill. We finally came to the forests and were ordered off the road and into the trees. They were very thick and tall pine trees.

We had not gone too far until we were signaled to stop and hit the ground. We were doing what the men up ahead were doing as we knew they were getting their signals from who ever was in charge. I believe Captain Miller was leading this column. The reason I say this, is because of what Sgt Behringer told me at the first reunion in Indianapolis, Indiana. He told me that Captain Miller had been gut shot real bad, and he had gotten a jeep to get him out of there. He did say that he joined up with some other outfit and had continued fighting until the battle was back under the control of the American units.

We were laying there when we heard the clanking sound of a tank. As they got even with Creech and me, it seemed as though everyone in the immediate area started firing at the same time. Germans and bicycles just crumpled down in one big pile. The tank stopped immediately and the machine gun mounted just below the turret in a ball, fired, spraying the woods where we were at. The bullets made a popping sound as they passed over our heads. We could also hear a lot of firing up ahead from the forward section of the column. If we had a bazooka, it would not have done any good as the rocket would have hit a tree before it could have reached the tank.

We were not having any effect on the tanks with our rifle fire, so we were ordered to pull back out of the forest and re-assemble back in the town. Creech and I crawled on our bellies backward until we had cleared the forest. I did not want to take my eyes off that tank. They never did fire their cannons. I suppose they figured the shells would have hit a tree before penetrating very far.

I have no idea how many of the men were hit while we were in the forest, but the ones that were in our immediate area were okay.

I want to say at this time before I continue that it was my understanding from Sgt. Behringer that Captain Miller had got hit real bad at this time – while we were in the forest and first engaged the tanks. I believe this is what he told me at the reunion.

At any rate, we and some more of the men started across the large open field that I mentioned had been on our left as we were advancing up the ditch. We reached the road that we had come in on while in the trucks. There may have been 12 to 15 men counting the Lt. As I look back on it now, it seemed as though most of us were a little upset at having no armored support or artillery support. It was like bear hunting with a switch as far as the tanks were concerned. We felt we could handle their Grenagiers and infantry, as least until we got support from other units of the regiment.

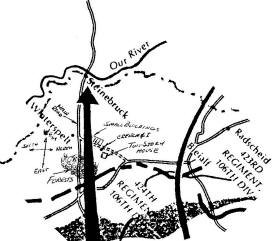

Since then I have read a book about the battle of the Bulge by John Toland, and it refers to the 424th having to pull back to protect the bridge crossing the River Our at Steinbruck. Or it would have been entrapped on the east bank and suffered the same fate that the 422nd and 423rd had encountered.

T The spot where we assembled on the road was approximately one half mile from the junction of the two roads. The Lt. said we would take up a defensive position there. He put some of the men in the small buildings and had Creech and I dig in across the road in front of the two-story house and he would take three men and take the top story of the house. There was an old German man and woman living in the house.

Creech and I were having a tough time digging as the ground was frozen but we finally got a hole big enough for both of us, but not very deep. We did have a good view of the road across a corner of the field we had just crossed. The men across the road had a good view of the hedgerow adjacent to the corner of the field leading up the road to the junction and the Lt. and his three men had a perfect view fo the opposite side of the hedgerow, the road and the road junction.

We held these positions the rest of the day and night, until the evening of the 17th. We were out of ammo and the Lt. called for us to come inside the house. I told Creech to go first and I would follow. The firing had ceased and we both made it into the house without drawing any fire. The Germans had set up a machine gun on the main road and it had been giving us fits. There was a one rail post fence at the edge of the road in front of us and the machine gun had literally shot it to pieces. We were trying to shoot it to pieces also, but I don’t think we ever got it. But we got some that were riding on bicycles.

The Lt. and his men had a field day. As we looked out the window they had been firing from, we could see dead Germans lining both sides of the road, in the ditch, and next to the hedgerow, leading all the way to the road junction. The Germans had tried to set up a small artillery piece in the middle of the junction but they never fired a round. They were laying all over the area.

The Lt. told us to break down our weapons and throw the pieces out of a back window in the room as the Germans would be here shortly. He had seen them taking men from the small buildings across the street. I want to say at this point, that the Lt. (Nelson ?) and his three men had done one hell of a job from their position in the top story of that old house. It’s no telling how many Germans they had killed.

It was only a few minutes until we heard the Germans downstairs, yelling Raus !, Raus !

The Lt. led the way telling us to pit our hands on top of our helmets as we reached the bottom of the stairs. Several of them rushed upstairs as we were motioned to go outside, where they started searching us. They then motioned for us to go towards the road and toward the road junction. Just from the look on their faces, I figured they were going to shoot us, especially seeing all their dead in the ditches along the road. They took us to the junction of the two roads where there were several more small groups of Americans. They then took us over to the side of the main road where neatly laying side by side were 8 to 10 of our boys. Each had been shot in the temple. One of the Germans started laughing and pointed his finger toward the side of his head and said “Kaput”. Several more of the Germans started laughing.

They then put us with the rest of the Americans who told us that the Germans said that they had pulled a white flag trick on them. They had been dug in and were I their trenches and had hoisted a white flag for surrender and when the Germans had almost reached them, the Americans had opened fire on them killing them all. The Germans then went after them with armored vehicles and this was their way of retaliation. This is one of the things I will never forget.

We figured out that we had been behind German lines fighting since late the day before as one of the men said he had seen the German armor go through where we were standing late in the day (December 16th), and never slowed down. The Germans were milling around through the group searching us again only this time it was for cigarettes, lighters watches and etc. All of a sudden we could hear an aircraft approaching from the Wet. As it grew closer and closer and then lower and lower, we could see it was an American P-47 Thunderbolt. I am sure the pilot was aware as to what was taking place as he sort of waggled his wings and gunned it and was out of sight in no time.

I feel real strongly about this – If we had had any air support, armored support or artillery support, the Germans would never have taken the town of Winterspelt. Any one of the three mentioned would have made a world of difference. Of course I kno wit would not have altered the course of things that happened, but we would still have had Winterspelt. I also feel that the men that were on the road that afternoon of the 17th had nothing to be ashamed of. We had given it our best shot.

At any rate, they had herded some of us into a root cellar under one of the few houses that were left standing and I suppose they did the same with the rest of the men. I guess you could say we were lucky, as there were some potatoes and turnips in the root cellar ans since we had missed our breakfast on the morning of the 16th,and had not eaten anything since, we ate peelings and all. Little did I know that the tops of the turnips would be my steady diet for the next five and a half months and to this day, I will not eat any cabbage or rutabaga turnips.

On the morning of the 18th, they Raus-Raused us again and we assembled back onto the road junction and we started our march further into Germany on the same road and direction that we had advanced into the forest on the 16th, when we ran into the tank trouble. We marched and then crammed into box cars and ride a ways, then march some more. I am going to make a rough estimate that were probably 30 – 40 men in this group that left Winterspelt. We arrived at Limburg, Stalag XII-A on Christmas Eve.

There were quite a few British there and they gave us a big cup of hot tea with milk in it and Lordy that was good. They had us assemble in a large courtyard where there was quite a large group of POWs already and more coming in.

There was an American Sgt. And some German officers sitting on some stands above the ground where they could view everything. This Sgt. Had a microphone and he started talking – saying that he had been ther for quite some time and he was the official spokesman for the Americans and that he acted as the go-between if anyone had a complaint. Then he stated that some of us would only be there for a short stay. The camp was crowded. There would be shortages of food and other supplies. We were to obey all rules and regulations which he read from a paper and that if any rules were broken, severe punishment could be the result. The more this guy talked, the more we wondered whose side he was on ?

After this was over, they put all of us in one large building, nothing but a concrete floor with supports for the roof and small windows at the top of the walls, right at the joint with the roof, so that you could not see out of them. There were so many of us that you had to sit up on the floor with your knees drawn up against your chest. No way could you lay down. There were two guys to my right and they were harmonizing on a song, “In the pines, in the pines, where the sun never shines, and you shiver when the cold wind blows.” Then, “Little girl, little girl, what have I done that makes you treat me so ?” I can still hear them singing those songs.

I asked my Captain the time of day, and he had throw his watch away. This was the first time I was close to breaking down. Here it was Christmas Eve and what a hell of a place to be. Tears welled up in my eyes. I wasn’t feeling real sorry for myself, I don’t think, but I feel that I was more angry and bitter about the way things were.

Anyway, the songs were cut short by the sound of air raid sirens from town. We were located right on the edge of the town, next to a railway switching station. I will say this, when those bombs started bursting, it seemed as if they were hitting right outside the building we were in. Glass was flying everywhere, plaster falling from the ceiling, the whole building shaking. It was darn near as bad as the artillery barrage back at Winterspelt. It did not last long. Somewhere along the way, we had been told the British bombed at night and the Americans in daylight. I don’t know, but it was real sad when morning came and we were told that one of the bombs had made a direct hit on the officer’s barracks killing 55 – 60 American officers.

I didn’t know why, but I had an awful feeling that our Lt. Nelson had got it. They had separated us from him when we arrived at the camp. I know this much, whatever his name was, he was one hell of a fine officer. Real cool headed back at Winterspelt while under fire, a take charge kind of guy.

The is one thing that stands out in my mind, but I have never figured it out and that is why the Germans would keep coming up the sides of the road from the road junction towards the old two-story house. They were just like sitting ducks for the Lt. and his three men. The only thing I can come up with, is that when the Lt. set us up in our defensive positions we had four clear fields of fire and there was no threat to our rear. I don’t believe the Germans knew from what directions the fire was coming from. The Germans were too good of soldiers to keep making that dumb of a mistake over and over.

Well, back to the POW status. They moved a bunch of us out Christmas Day. I was ready after the bombing. We started what turned out to be a very long march from Limburg to Luckenwalde and Stalag III-A. I had gotten separated from Creech at Limburg. Sure missed him ! I wished there was some way I could find out if he made it all the way. I don’t remember where Creech was from – Georgia or Alabama ?

Only spent three days at Stalag III-A. Got to clean up a little and write one letter home and then I was picked with a group that was going to be sent to a work camp at Wunsdorf, Germany. It wasn’t too far from Stalag III-A. About 29 KM from Berlin. The town of Wunsdorf was small, but they had a very large Panzer Officer training school. But as I would find out later, very few trainees at that time. We had to pass right by it going to our new home. It reminded you of most any large college campus in the States. It had large 3 and 4 story buildings. Probably covered several square km’s of area.

We arrived at the camp which was only a short distance from the Panzer school. Probably about three miles from the center of town. It was a very small camp with only six barracks which were 60 – 70 feet in length. They lined us up and gave each of us a number and assigned us to a barracks. The best I can remember, there were approximately 70 to 75 men. The Camp Commander then read us the rules and regulations and said he hoped we would be better workers that the Russians they had just moved out of there. He said the Russians were trouble-makers.

We would be assigned our work duties by our numbers and said some would be doing farm work, some working at the school and some working at the coal yards. He said all the work would be in compliance with the Geneva Convention. We would be fed each day – one slice of bread with margarine and coffee for breakfast – one bowl of soup and a slice of bread for lunch – and a slice of bread with margarine and coffee when we returned from our job duties. A day consisted of sunrise to sunset.

I was assigned to a group to work the coal yards. He pointed to a round metal stock tank (frozen over with ice) and said that is where you can bathe. He pointed to a slit trench and said that is the toilet. This was really something to look forward to for the next few months. He said a guard would break the ice on top of the water each morning. We could heat the water on the stove in our barracks in the metal bowl they gave us for the soup.

We had to carry the bowl with us to work each day and the soup would be brought to each group wherever you were working.

Well, things didn’t look too good and as it turned out, our soup was grass soup. That’s what we called it anyway as that is what it looked like. Tasted even worse, very bitter and sour tasting. The bread was sawdust bread. I imagine about 50% sawdust and 50% flour. The coffee was ersatz and the margarine was I know not what.

The first thing I noticed at the coal yard, were the Frenchmen. They were in charge of getting the boxcars moved up to the platform and then having the horse-drawn wagons moved up on the opposite side while we would shovel the synthetic coal into the into the wagons. The wagon beds were tall and “V” shaped and when we would get one full, it would pull out and another would move up. This went on all day long.

The French had a glassed in office where they could see how things were going. They had a large stove and they would sit by it, laughing, eating, drinking, talking. The only time they would do anything is when we finished unloading a boxcar, they would get on the phone and have the empty one moved and another full one brought up. Our German guards stayed in by the stove with the French, laughing and talking with them. There were usually 4 to 5 Frenchmen at all times in the office. We figured they were French POWs and we asked them one day if they spoke English. One said, “oui – oui”.

We asked him why they did not have guards and where did they stay. The one spoke in French to the others and they all started laughing. He then turned to us and said that each of them had a woman whose poor husband had been killed in the war. The Germans knew they were not going to run away, because, as they say in America, “We have it made…”

Needless to day, we didn’t have much respect for the French. There was an old cat that hung around their office and they told some of the men that if they caught it, they would take it home, butcher it, fry it up and bring it back to them. They said it tasted just like rabbit. Several of the men caught the cat and put it in a sack and gave it to the Frenchmen. Sure enough, the next day they had a sack of fried cat for the guys. They did not want to eat it then and there, but wanted to take it back to camp and eat it in front of the other men, telling them that they fed them fried chicken at the coal yards. Would anyone want to trade jobs, they asked as they ate the cat ???

It wasn’t so funny later that night as they all became real sick, high fever, vomiting and some with bad stomach cramps. The Camp Commander sent a couple of the men away to a hospital, so he said.

The work was very hard and if you did not get a full shovel or a full pitchfork, they would poke you in the back with their rifle butts ans holler at you. The Frenchmen said they wanted our shovel or pitchfork full. This was very hard and back breaking work and especially on one bowl of grass soup that would be soured when it finally arrived by horse and wagon.

The briquettes of coal were synthetic and much heavier than regular coal. They were approximately 8” by 2.5” by 2” with rounded ends and looked as though they had been made in a mold and compressed under high pressure. They were a brownish grey color and had an oily smell. They were very easy to break and they would not make a flame, burning about like our charcoal. They used it to heat with and also to fuel their vehicles. They had a tank mounted behind the cab of their trucks (not on front-line vehicles). Looked like a hot water heater but the guts were quite complicated as I had seen a cut-away drawing of one in an office at the Panzer School when we were moving some furniture. It had a door at the bottom and each vehicle carried a tow sack of the coal and one of wood chips and they would throw in a couple handfuls of coal and of wood chips whenever the vehicle began to lose power.

The cut-away drawing that I saw showed that the coal and wood formed quite a bit of smoke and it then traveled through some soils and then into the carburetor where it became a vaporized gas that burnt.

One day they ordered us to fall out and began calling out a couple of numbers. Mine was called. They told us to load up on a truck that was waiting and that we were going to Berlin to unload a barge of flour. The barge was tied up ato a dock on a canal. There were six of us unloading and four stacking the sacks on a flatbed truck. Each sack was 45 kilos which I think is close to 100 pounds. It took tow of us to lift a sack. The only thing good I can say for that day was that they gave us a bowl of the same soup they gave the guards. It looked like some kind of oatmeal and had a few pieces of meat. It had a good taste. We also missed the bombing raid that took place while we were gone. When we arrived back at Wunsdorf there was debris all over the road, pieces of trees, bricks and a large part of the town was burning. The Panzer School had several buildings that were completely demolished and the rest had heavy damage. We finally got back to camp and noticed some Germans digging on each side of the compound, about 15 to 20 yards from the fence. There were two bombs, one on each side, that were duds and the Germans were going to defuse them. They were buried about halfway into the ground. One of the men said they were 500 pound bombs.

The men in the camp had been ordered to get in the bunker, which was only a deep trench behind the barracks. We were told to get in it also.

Our guys said American B-17’s had done the bombing, and I am sure their target was the Panzer School as that is where most of the damage had occurred. We spent the next several days cleaning up the rubble. Some of our men cam in one day and said they had seen some American Air Force guys in a wire cage down in the middle of town and the German townspeople were screaming at them and throwing things. But there were German guards ordering them to back away from the area, but not using too much force.

We knew things were getting bad at Berlin because there were very few nights that they were not getting bombed, and I mean heavy. You might say we had a ringside seat as we were only about 28 km from Berlin. Our guards would make us go to the bunker as soon as they heard the air raid sirens from Berlin. The first thing would be the Christmas trees that were being dropped to light up the targets. Then the searchlights would begin criss-crossing the skies. When the bombs hit, it would light up the whole sky and the ground was shaking even as far away as we were. It had to be those block-busters. All of us had a real good feeling even though we were covered with lice and sores and hungry. That work camp we were in was one bad place to be as a POW.

Finally one day they had us fall out and announced that we were being moved to another camp. Most of us felt that we would never survive another march. My feet were in very bad shape. They were real black and all my toenails had come off. I had no feeling in my feet and legs, but I suppose we all felt that we could crawl on our hands and knees to get out of there. I know I would.

Anyway we got started helping one another as best we could. One thing that helped is that the weather was getting warmer. I do not know how long or how far we had marched until we came to the town of Altengrabow and Stalag XI-B. They took us out to a very large open area with nothing but barbed wire fencing and four guard posts at each corner. There were some tents scattered around. We went through some gates and after we had entered, they just closed and locked them behind us. We decided that we should try to stick together. There was an American that approached us and said to follow him and that it was very important that we stay together. We came to a tent where there was a whole bunch more of Americans sitting, laying and standing around under this large tent which did not have any sides, just the top.

There were POWs from every Allied nation. There were Russians, British, Sikhs, Scots, you name it. I believe they were all there. There were no guards inside the compound, just up in the four guard towers.

The American who had met us at the gate told us to sleep with one eye open especially if you had any cigarettes. As the Sikhs could slip up on you during the night and would think nothing of slitting your throat for a cigarette. I don’t believe any of us slept that night.

We were there only a couple of days, when we woke one morning and noticed all the guard towers were on fire and the POWs were going crazy. Especially the Russians. One of the British said that the guards had left early that morning and the Russians had set fire to the towers and broken down the gates and were heading for town.

The American who had met us at the gate when we arrived, told us to stay in one close group as there would be a couple of American officers parachuted into the cap to get us organized and ready to move out as we were going to be liberated. I have never figured out how he knew all this. I never did see any parachutes, but sure enough, it was only a short while until a couple of American officers, (a Major and a Lt. Colonel), showed up and ordered us to stay right where we were and not to try to go off on our own. He said the Russians were in the town looting, raping and killing.

They said trucks would be here shortly to get us out of here. They had us form up in groups of 18 to 20 men. It wasn’t but a short time until the trucks started rolling in the gates. It was a beautiful sight and even though we were in pretty bad shape, we did not have any trouble at all getting in the trucks.

Soon we were rolling down the road to freedom. I do not have the words to express my feelings, as we started passing long lines of German soldiers heading the same direction. They had disposed of their weapons and I’m sure they wanted to surrender to the Americans. They did not want to fall into the Russian hands.

This all took place on the 3rd of May, 1945. We were taken to Hildesheim, Germany, to a large air base where the first thing they did, was de-louse us. We were issued shaving and bathing equipment. After showering and shaving, we had a quick haircut and a sort of a physical, we were beginning to resemble human beings again.

They had a mess hall and most anything you wanted to eat. But they cautioned us to take it slow and easy as our stomachs had shrunk and we could get real sick, real quick, by over-eating. I had lost 30 pounds while in captivity.

They then took us out to the edge of the runway and soon a steady stream of C-47’s were landing. We would load up and they took right off again. I was taken to a hospital at Reims, France. After a short stay I was taken by hospital train to the coast where I boarded the Monticello for my return to the United States.

We landed at New York. I had a train ticket to Waco, Texas and orders to report to Ft. Sam Houston after a short stay at home. I was at the Fort when the war with Japan was over.

I was then ordered to Camp Livingston, Louisiana, where they gave me a Corporal rating and I became part of the cadre with the job of training the new recruits. I did not have enough ASR points for discharge, and was there for only a short time when a bill was passed to discharge all ex-POWs for the convenience of the Government.

I was sent to Camp Joseph T. Robinson, Arkansas, where I was discharged December 3rd, 1945.

I am still married to the same girl as when I entered service. We had three children, two boys and a girl. We have six grand-children, five boys and one girl.

Our oldest son is retired from the Air Force after 20 years. We lost our youngest son, age 42, last year to a brain stem hemorrhage. He was a Navy veteran. Our daughter, who is the baby, is 40 years old and lives in Ft. Worth, Texas. Our oldest son lives in Sedalia, Missouri.

I spent 23 years as a tool & die maker with General Dynamics in Ft. Worth, Texas and spent two years in Tehran, Iran teaching tool & die. I retired from Texas State Technical Institute where I was teaching in the machine shop, in June of 1987. My wife and I are looking forward to being in the next reunion in Chicago if the Good Lord wills.

Written January 26, 1989

Respectively, Robert Jeters |

|

Page last revised 02/18/2007 |