|

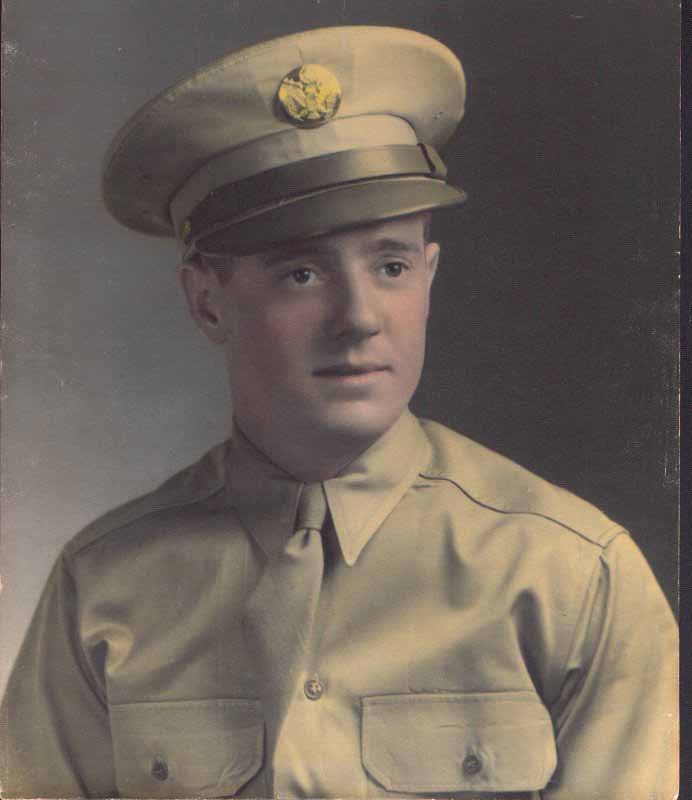

John Gatens |

|

|

PREFACE

The following narrative of my time spent with the

106th Infantry Division is made possible, in part, as far as dates

and times are concerned, by reference to a short history of the

589th Field

Artillery Battalion written not long after the end of the war by Francis H. Aspinwall, who was assigned to Headquarters Battery, and either kept a diary

and/or had access to records prior to writing his booklet titled

"History of the 589th Field Artillery Battalion". I also used part

of Frank's text as a reference

where other units and events are mentioned that I had no knowledge of at the

time. ************************ REFERENCES: Autobiography by John R. Schaffner I, along with a whole train load of 19 year old draftees, joined the 106th Infantry Division at Ft. Jackson, S.C. in March 1943. I was assigned to "A" Battery, 589th Field Artillery Battalion and placed in the gun section under Sgt. Johnnie B. Jordan. There were no assigned positions at this time. After about three weeks of orientation about chain of command, close order drill, making a G.I. bed and physical fitness, we received the four 105 howitzers that make up a firing battery. A section is made up of nine men. A sergeant is in charge of the section. Next is the Gunner (most important position when firing,) his job is to set all firing commands, on a high power sight and traverse the barrel to correct direction to be fired. This is the procedure, when the firing command comes down from the observation post. This is called indirect firing. In direct firing (when the target is in view) the gunners responsibility is to set the elevation, then track the target and give the order to fire. The Number 1 man's responsibility is to set the elevation for indirect firing. The Number 2 man's responsibility is to put the shell into the barrel. The other four men prepare the shell for firing - the type of shell to be used as given from the observation post. We had three types - armor piercing, high explosive and time fuse. Each shell had seven powder bags. These powder bags determined how far the shell will travel. You can use all seven or as small as one. If one is used, the target is way too close. The last man is the truck driver. During our early training period, each man was being observed by the officers. Ten men were chosen to take the test to be gunners. Only four made it and I was one of them. This carried the rank of corporal.

We accomplished our basic training and practiced division

scale maneuvers at Fort Jackson, S.C. during the remainder of 1943.

Although, when I arrived at Ft. Jackson early in March

and the weather was wet and cold, it soon turned hot and dry.

The camp was swept with a dry breeze frequently and the fine dust got

into everything. As I recall that first morning at Fort Jackson, the

sergeant came into the barracks with a lot

of noise, telling us to get up and get going and how to dress. It was

still dark, cold and raining hard and the wind was

blowing the rain in sheets against the barracks as we were awakened.

My thoughts were, "Well, with the weather like it is, I guess we will

have to stay inside today." Was I ever mistaken, the first order we had

was, "EVERYBODY OUT FOR ROLL CALL !!." So, steel helmets and raincoats, we all lined up

in the rain, out in the battery street and sounded off as the

sergeant called our names. As I stood there with the rain beating on

my helmet and running down the back of my neck, I thought that it sounded

like an attic with a tin roof. We soon learned to disregard the weather,

whatever we were doing, it was never a deciding factor. We were in the Army

now. Our division was referred to as motorized but we walked everywhere. When we finally began to use the vehicles, dust respirators and goggles had to be issued. The dry dirt roads throughout the maneuvering area sent up clouds of dust that infiltrated everything and made it impossible to breath or see ahead. At the end of the day we were mud balls from the dust and the sweat. All of that summer and fall the division was active in the field practicing those skills needed to defeat the enemy.

We had been issued the Carbine M-1 and taught everything about it. How to take it apart, and keep it clean, and to

love it and never be without it. It was to become a living part of us. When

the day finally came to actually load it with live ammunition, we were as

excited as being on a first date with a

real live girl. The temperature at the firing range must have been at

least 100 F. The targets were placed across a bare,

sandy field at 100, 200 and 300 yards. As we tried to zero in on our

targets, the hot air shimmering off the sand made the "bull's eye" seem to perform like a belly dancer.

Nobody qualified, so the firing

for record was postponed for another day. When the time came, I made

"Expert" with the carbine. On

occasion, in later days, I have heard disparaging remarks made about this weapon, but I never had any problems with mine, then or

later. AND, it was made by the Rockola Juke Box

Company. We now had four complete gun sections under the command of Lt. Graham Cassibry. His responsibility was to make us an efficient, accurate and fast firing unit. This he accomplished because he won the hearts of every man and they would do anything for him. Under his command we won the title of the best firing battery in the battalion. We were the youngest group of men ever drafted into the U. S. Army. Now they had to find out how much these kids could take. I don't think they missed one torture test available. Most of our time was spent camped in the woods. We had day and night firing missions. Twenty five mile forced marches. Dry and muddy infiltration courses. We lived on bag lunches, so much so that we became known as "The Bag Lunch Division." Low and behold, after many months of really grueling training we passed with flying colors. We were now ready for the next phase of our training.

After New Year's holiday, the division then moved from the

comparatively comfortable Fort Jackson to the Tennessee

Maneuver Area for the period of January, February and March 1944

where we became accustomed to living in the "field". The cold and wet weather during those three months was extremely

difficult, with some 30 inches of rain, setting a record of some kind for the area. We spent a great deal of time just

extricating the howitzers and vehicles from the mud. Everybody was wet and

cold most of the time. We learned to exist with these conditions and I can't

recall that anyone even caught a cold.

On one particular day we were occupying a farmer's pasture that was about

eight inches in snow when one of his cows gave birth to a calf. That was a

"first" for most of us "city

guys" on the scene. When the maneuvers were finally over we were confident that we could handle anything. Before the

division had completed this phase of our training we heard of quite a few

casualties. During a crossing attempt of the Cumberland River at

flood stage, a raft loaded with a truck and a group of infantry G.I.'s upset

in mid-stream. We heard that there were no survivors. In our battery one

night we had a man run over by a 2 1/2 ton GMC, backing to hitch on to a

howitzer. We heard later that he recovered, but he never re-joined the

outfit. One of our simulated battles required that we cross the raging waters of the Cumberland River. To get us across was the responsibility of our Engineers. What they had was a pontoon type raft. It was large enough to carry a 2 & 1/2 ton truck. In the rear and on one side was an outboard motor. When it was our turn to cross there was a group of old time farmers gathered around watching what was going on. They kept shaking their heads and telling us we will never make it. They convinced me, and I would have waited for the river to stop raging. However, when the Army says, "GO," you go. The gun and its crew had to go first. The thinking was, that if we didn't make it, a truck, alone on the other side would not win a battle. So off we went. There were two engineers on board. One worked the engine and the one up front give directions. I must say, they were very good. We headed upstream against the current. The engine roared full blast. While headed upstream he was also moving across at the same time. When we were approximately 2/3 of the way across he started heading downstream. Now I really got scared. It took us 1/4 of the time to go down as it did to go up. Now, while traveling at this rate of speed he had to slow it down so we could get in to the dock. It took a few tries but he did get us in safely. Now he had to go back and get our truck. Lucky him. We did have some fun times during all this serious training. I remember one of our early morning missions we had to move positions. When we arrived at the new position my gun was placed in the front yard of a farmhouse. The occupants of the house were all sleeping because there were no lights on. When we were set up and a fire mission came down all four guns fired. On these missions we fired blank shells. They made the same noise as a real shell, however, no projectile is in flight. All of a sudden all of the lights in the house went on and the farmer came running out with his shotgun, ready to kill us all. After he calmed down his wife came out and asked us if we would give her fifty cents a man she would make us coffee, eggs, bacon and hot biscuits. We all accepted and believe me after what we had been eating we hoped that we would never leave this position. The weekly routine while on this phase of training was, every Monday morning we started out on a new battle problem. One week you would be the attacker and the next you would be the defender. The battle lasts for five days, until Friday. Everything was realistic. One of the judges would come around and if he pinned a tag on you "wounded," you had to call a medic. The tag would specify what kind of wound you had. The medic would treat the wound and if it was serious, off in the ambulance you would go to the Aid Station. You now stayed there until the battle was over for that week. I tried to bribe the judge many times for a serious wound, but I never got one. On one of the missions the battery was judged to be captured. This gave us two days off. On Friday the problem was over. Every Saturday we spent cleaning up our equipment. This was a hopeless job. Everything was covered with mud. Even after you got it somewhat clean it didn't stay that way for long. Saturday evening and Sunday passes were given out on an alternating basis. It was great to go to town, find a place where you could take a good hot shower and then sit down in a restaurant and have a good hot meal. Some of the time we were close to Nashville. Many of the southern guys would line up and go to the Grand Old Opry. Us city guys thought they were nuts.

One of the many stories that I could tell about my good friend Lt.

Cassibry. He came from a very wealthy family. He was a brilliant young man.

He was not a military man. Being young and rich he was more of a playboy

type. He treated his men more like friends than subordinates. He had one bad

fault, he was an alcoholic. He never let it interfere with his duties, but

on his time off he would come to the barracks and share his bottle with the

men that were drinkers. I was not a drinker, this made him trust me and I

became one of his favorites. Every time he had to go someplace he would

order a jeep and I would have to drive him. Officers were not permitted to

drive and I didn't even have a G.I. driver's license. With that background

we are now back to Tennessee. One Saturday night a bunch of us were sitting

around a fire and along comes my favorite lieutenant. He calls out my name

and says, "Follow me." We go down to the motor pool and he

requisitions a jeep and off we go to town. He tells me to pull over and stop

by a taxi stand. He went into the office, came out with another man, they

get into a cab and leave. Half an hour later they return. The lieutenant

gets out with a big bag in his hands. Into the jeep and back to the guys

still sitting around the fire. Out comes two bottles of Vat 69 scotch.

Tennessee is a dry state. I don't know where they went or how much it cost

him, but I bet it was plenty. On 2 April 1944, the division moved again, from Tennessee to Camp Atterbury, Indiana, near Indianapolis. We traveled in the division vehicles across the mountainous areas of Tennessee using the unimproved back roads. In some places on the switch-back curves it was necessary to un-hitch the howitzers from the trucks in order to make it around the bend. The howitzers were then man-handled by their crews who struggled to get the piece hooked up again so they could proceed. The division made it to Camp Oglethorpe to spend that night. As we dismounted the vehicles and were assigned barracks for the night, the officers informed us that this post was the WAC training facility and anyone found outside our restricted area was subject to be hung or worse. Here again my favorite, Lt. Cassibry, came along and asked me and a few others if we wanted to go to the PX for a beer. The only problem with this is that the PX he wanted to go to was in the WAC area. Not being brave enough to refuse an officer, we went. We met some very nice WAC's. I must say here that after coming from the muddy fields of Tennessee we looked like we had come from a war. They indeed must have felt sorry for us. They were also told not to entertain these overnight staying G.I.'s. Before we could finish one bottle of beer the MP's came in. Now my playboy Lieutenant took over. He took the MP's over to a corner and with his charm talked them out of turning us in. They did however, escort us back to our area with a warning that if they caught us again we would be turned in. The next morning was clear and cold when we loaded up to continue the move to Camp Atterbury. Again we had to travel on the small, lightly traveled roads. The scenery was very nice, but no girls to whistle at. Our next night stop was at Ft. Knox, Kentucky. For me this was a blessing. My brother Jim was stationed there. We were escorted to our bivouac area. This was an open area on the outskirts of the camp. No barracks this time. I spotted a chapel not far from our area. I took off and entered the chapel. There was a chaplain in the office. He didn't know what to think of me. This was an armored camp and muddy artillery men didn't show up here. I told him who I was and that I had a brother on this base, could he find out where he was and get me to him. He located him and called a taxi for me. Jim was in a heavy tank corps. They had their own group that was self-contained. I went into the office and a soldier asked what I wanted. I told him that I wanted to see my brother. He said, "Wait here." When Jim came around the corner and saw this cruddy looking GI he almost didn't recognize me. When he introduced me to his friend, the First Sergeant, he told Jim to take me down to the barracks and clean me up. Being their own group, they had all kinds of supplies. Jim asked me for sizes and while I was showering he went and got me a complete new set of clothes. I think they burned mine. In Ft. Knox a First Sergeant has his own home supplied. He was kind enough to invite Jim and me to supper and to stay the night. What a joy, a real home cooked meal and a real bed. Heavenly. After supper he drove me over to where the outfit was staying. I left so fast I never asked what time we were leaving the next morning. My gun crew was all around a fire trying to keep warm. Me, in my new uniform, walked up to them. Being dark, and only the light of the fire, I told them to put out the fire, they were not allowed on this post. Not recognizing me, you can guess where they told me to go. The look on their face when they did recognize me was of complete surprise. When I left to go to my nice warm bed, they all wished me a pleasant good night. Ha!, Ha!, Ha!, that will be the day! No one in that outfit eats until the First Sergeant has been seated. With all the men seated, we walked in. They were used to the Sergeant and Jim, but all eyes were on me. Who is the special Corporal that can sit at the head table? It felt very good. Then it was time to say goodbye. I didn't see Jim again for over a year. Until the war was over and we were all home again. We then left for Camp Atterbury, Indiana. The civilians in Indiana treated the G.I.'s with open arms whenever we were on pass. The hospitality was unlimited, even invitations to private homes for Sunday dinner, if you could get a pass into town. Invitations were posted in the service clubs for anyone desiring to take advantage of them. This is the way that I remember Indianapolis, Indiana. It was what we called a "G.I.'s town". We were toughened to the task ahead, training was becoming routine, and everybody just wanted to get at whatever laid before us. At this time the 106th was considered to be one of the best trained divisions in the Army. There was a great deal of pride and "espirit de corps" among the men. In the parlance of the day, we were a "Crack Outfit." I was lucky again. One of the fellows in my crew lived in Chicago. His name was Phillip Diasio. We called him "Nippy." Every time we could get a three day pass we would go up to his home. His mother and father were very nice people. He also had two sisters. On Saturday night Nippy, his girlfriend, Margie (his sister), her girlfriend, George Sparks and me, would go to the loop. In Chicago, The Loop is like our Times Square. It was a sailor's town. Great Lakes Naval Base being there. This made it nice for us, not too many soldiers. This is where I got my first taste of bars. The first one we went into was very embarrassing for me. When asked what I wanted to drink, I didn't know what or how to order a drink. Lucky for me one of the girls asked for a Rum and Coke, so, liking Coke, I said, "I'll have one too." On Sunday we would all go to church. After church his mother would cook a typical Italian Sunday dinner. This took us about four hours to finish. Just in time to run for the Greyhound Bus back to Indianapolis. This is the only time that we would get a bad deal. The only way back to camp in the early morning hours was by cab. We got a cab for there were many GI's all waiting for one. The cab would only take you a short way out of town and drop you off at another station. He would leave and go back for more people. Now it was a long wait for the part of his cab co. to pick you up for the ride to camp. Many times we would only get an hour of sleep before reveille. Being young and needing something other than Army life, it was worth it.

During May and June a large number of 106th Division men were

transferred to overseas units and were replaced by men from Replacement

Centers at Ft. Bragg N.C. and Camp Roberts, Cal. Training had to start all

over again. These new men were mostly from units no longer considered necessary to the war effort;

ASTP programs, pilot training, anti-aircraft and coast artillery, etc. The

need now was for infantry. Casualty numbers in Europe and the Pacific were climbing and it still required

the Infantry to take and occupy territory. Not long after we arrived at Camp Atterbury came a sad day for me. My pal, Lt. Cassibry, was a big thorn in the side of all the brass in A Battery. He was a superior artillery man, but in their eyes, not a good leader. His drinking and lack of Army discipline was cause for a change. In our eyes he was the best. They transferred him to C Battery. This broke his spirit. He had taken us from green young civilians to the best firing battery in the Division. He then applied for Liason Pilot Training. I wrote to him many times while at training base. He loved it there. I don't know the circumstances, but he cracked up a plane so they washed him out. I really think our Battalion Commander had a little to do with that. Knowing how good an artillery man he was, Lt. Cassibry was transferred back to Battalion Headquarters. I never did see him much after. His pilot's training probably saved his life. At the height of the Bulge an order came down to burn the artillery planes because some of the pilots were not around. Lt. Cassibry volunteered to fly one out. He did and survived the war. We now in turn received as our Battery Exec., a Lt. Kiendl from C Battery. We knew of him and his reputation. He was a real GI and very strict to the book guy. After losing our best friend, this guy didn't set too well. We spent many months under his leadership. I guess it was all for the better. We had to train a group of new men in a short period of time. The training was as usual, with very little let-up and grueling. A very surprising thing happened just before leaving Camp Atterbury.

Lt. Kiendl was transferred to B Battery and we in turn got as our Battery

Exec Lt. Eric Wood. To this day even Lt.

Kiendl don't know the reason for the change. Lt. Wood was more of the

Cassibry type, except he was from a military family and very professional.

His father was a General on General Eisenhower's staff. At the same time,

our Battery C.O., Captain Elliot Goldstein was promoted and transferred to

Battalion Headquarters. We then got Captain Aloysius Menke. The division was alerted for movement overseas in September 1944 and moved by train to Camp Miles Standish, Mass. on 9 and 10 October. The following month was spent awaiting for transportation during which time the equipment was packed and training was continued. During our train movement the train stopped at Trenton, N.J. We opened the door to look around. A couple of civilians got on the train. We told them they were welcome to come along, that we were headed for overseas. When they saw nothing but G.I.'s it didn't take them very long to back off. We had many Southerners and Western people in our outfit. Our next stop was in Grand Central Station in New York. They couldn't believe that we had gone under the Hudson River and now were under the ground in New York City. As usual in the station in New York there were people out to make money. The men were carrying big baskets filled with sandwiches and candy bars. Others had sodas and juice. Needless to say they made lots of money on our gang. Camp Miles Standish, Mass. was a staging area for the troops awaiting shipment overseas from the Port of Boston. All of our equipment had been packed up and was on it's way overseas. We spent most of our time with physical fitness and classes on abandoning ship. Glad we didn't have to do that. Nightly passes were given for a strict 50 miles radius. Also, no telling anyone that you were waiting for a ship for overseas. Here is where I, (one of the few times I disobeyed orders,) along with two others, took off for home. We hitch-hiked to Providence, Rhode Island, then took the train to New York, raced to the bus depot for a bus to Paterson, N.J., then another bus to my house. Of course my parents were very glad to see me. Spent a few hours with them and a few hours with Ann, my future wife. At around 11:00 PM my father would drive to New York to catch the train back to Providence. Many mornings we almost didn't make it back in time. One morning we didn't make reveille. In a Port of Embarkation this is like desertion. When we got in the men were already gone for the days workout. Lucky for us our first sergeant was from New York. All he said was, "I know where you were. I won't report you this time, don't let it happen again." I went home about four times. Each time I would tell them, "When I don't come home anymore you will know that I am gone." It was only later on that I realized what I was doing to my father. This meant that he didn't get home until around 12:30 AM. He had to be up again at 05:30 to get ready for work. I'm sure that when I was a POW what they had to go through, They were glad that I did make it home when I did. November 10 the Battalion moved to the Port of Embarkation at Boston on special trains from Camp Miles Standish. It rained hard most of the day and the troops were soaking wet by the time they boarded the train. You know how it is with the Army, hurry up and wait. After a short ride we de-trained directly on a covered pier and were served hot coffee and stale donuts by the Red Cross. Couldn't have tasted better. Everyone was kept moving, leading immediately onto the troop transport USCGSS Wakefield, the former luxury liner SS Manhattan, sister ship to the SS Washington and one of the largest ships ever built in America. The battalion occupied D and E decks forward, sharing the ship with the 590th, 591st, 592nd Field Artillery Battalions, Headquarters Battery, Division Artillery, and the division Special Troops. The ship was crowded, there being 5 canvas bunks on pipe racks between the deck and the ceiling with precious little space left for passageways. We kept our packs and duffle bags in the bunk with us. Very few men were on deck at about 1630 hours when the ship slipped out of the harbor in the fog and driving rain. 11, 12, 13, 14 & 15 November - The North Atlantic was violently rough and few of us (including me) escaped becoming sea-sick. Two meals a day were served to those able to eat. To get the meals necessitated standing in an hour long chow line that started in the compartment, wound up the stairs to the next deck and ran along about half the length of the ship to the "mess hall". There was nothing else to do anyway, so it was a welcome break in the monotony and it got us away from the bunk area for a while. And, it didn't smell good down there either. Chow was served on a stainless steel tray without regard for any niceties. You could have your ice cream on top the mashed potatoes or if you preferred, in the beans. As one received his food, he would proceed to the "stand-up height" steel tables to eat. You had to hang on to both the tray and the table to eat. The ship was rolling, so that if you didn't hold on to something you could end up in your neighbors chow tray. Nobody could go out on deck in this weather. About the third day out the weather became better and the seas smoothed out some. It was now possible to get outside for a breath of fresh air once in a while without being swept overboard. Our course must have carried us farther south. The ship moved along fast and alone. The possibility of an encounter with a German sub was on everyone's mind, but nobody dwelled upon it. The ship was considerably faster than any German sub, I don't know about German torpedoes. Nothing but the cold winter ocean was in sight for about six days. On the afternoon of 16 Nov. another transport was sighted as we were nearing the British Isles. A destroyer escort also appeared to guide the ships through the mine fields at the entrance to The St. George Channel and protect against possible sub attack. The water became extremely rough again and the destroyer escorting us completely disappeared in the troughs as it made way off the beam. This actually was a comfort since it made a torpedo attack highly unlikely. Our ship literally plowed through the giant waves that crashed over the deck. The sailors on the "can" must have been taking a real beating. We must be getting close to England because K-Rations were issued today for our first meal on shore. November 17th found us traveling St. George's Channel with the mountainous green coast of Wales on the right and in the far distant left, the east coast of Ireland. Plenty of traffic was passed that morning in the channel and the troops on deck were straining to get their first glimpse of England. The haze and fog pretty much prevented any sightseeing on this leg of the trip. In the afternoon our ship proceeded up the English Channel for Liverpool. The weather was deteriorating as the day grew late and the ship, being in the channel with heavy traffic both ways, had to proceed slowly. When we were approaching the harbor at Liverpool the visibility was down to zero. I don't know how the pilot ever found a place to tie up. We docked at about 1600 hours. It was already dark and a drizzling rain and fog enveloped everything at the blacked out city. The 589th was the first outfit off the ship at about 2000 hours. As we left the ship it was to the music of a band on the pier. Music or not, we were all happy to be on land, even if it wasn't dry. The troops came off the ship marching in a file of two's, with full packs and toting a duffel bag on the shoulder, from the dock area to the rail station, maybe three blocks away, and the scene was like something straight out of a Sherlock Holmes movie. Fog, wet cobblestones, the city blacked out and quiet except for the sound of the troops walking uphill through the narrow streets. No talking much, nobody out on the street to watch as we marched by, just apprehension as to what was coming next. We made it to the rail station after the short march and after another Red Cross coffee and donut welcome, boarded the train. When the train was fully loaded, the doors slammed and with a shrill whistle, we were off to Glouster. The battalion arrived at Glouster at 0400 on the morning of the 18th and, after departing the train, was met by the "advance party" which had left Atterbury about three weeks ahead of us. We were led to the camp situated at the edge of the town. It was small, and had previously housed the British Gloustershire Regiment. The battalion was housed in individual barracks of about 20 men each. The double decker bunks were equipped with straw stuffed mattress covers and we had to dis-place all of the mouse families that had taken up residence there in the straw since the last group occupied the place. There was one small pot bellied stove, burning soft coal, to ward off the chill, and the "ablutions" were in a separate building at the end of a concrete walkway about 150 feet away. At night, in fog and blackout conditions, you could not see your hand in front of your nose. No exaggeration, it really was that dark. To get to the "ablutions", one had to inch along the walkway until he bumped into the door of the other building. It was best to take care of business while there was still some daylight. One large mess hall was shared by the 589th and 590th FABn's. Many things in the U.S.A. were rationed. Almost everything in England was rationed. The reason for this was because almost everything was sent to the military. Food, of course, was one of the biggest items. This leads to my first trip to the mess hall. There was a big sign on the wall that read, “Take all you want, but eat all you take." Going through the line, I came upon a pot of what I thought was mashed potatoes. Being hungry, I told the guy to let me have a lot of this. He did just that. Further down the line, I came upon another pot, but this one did have mashed potatoes in it. I then asked him what this other thing was. When he said, "Parsnips," my appetite suddenly left me. I don't like parsnips. Remember the sign? MP's were at the garbage cans making sure you didn't waste food. Now I found out who my friends were. No one would take any from me. I was the last person out of the mess hall that night. I had to eat all of it. I learned to ask first when in doubt. The period from the 18th to 30th November was spent in re-equipping the division with all of the necessary implements of war. Vehicles, weapons, ammunition, rations, clothing and what ever else was necessary was drawn from depots all over the area. Some limited training was carried on and a few "short time" passes were issued, (and some guys went "over the fence"), but there was really no place for us to go except into Glouster, a "one movie town." The town was blacked out and all businesses were closed by 2000. We began to appreciate the difficulties of living in a war zone. Because of my experience in Camp Miles Standish, I didn't go over the fence. Another reason was that the First Sergeant had promised me, that if any three day passes were given, I would be first on the list. The reason being, he knew, that I came from Port Glasgow and I would be very happy to see my relatives. None were given, so I didn't get to Scotland. Many times as a POW, I wished that I had gone anyway. On 1 December we loaded our equipment onto the vehicles and departed the Gloustershire Barracks in convoy about 0530. We drove to what was known as a casual camp, which was just outside Weymouth (Portland Harbor), and arrived at about dusk. C-rations were issued for supper that night and we were given cots to sleep on in some temporary barracks on the site. This was the last time for a long while that we would be afforded this kind of comfort. At dawn the next morning, 2 Dec., we loaded up again, and in convoy, moved down to the harbor where we were issued donuts, coffee and sea-sick pills for breakfast. Life preservers were passed out for good measure. They were a rubber tube that belted around the waist and could be inflated using two small Co2 bottles, (or by blowing into a tube.) I can't imagine that they would have done much good should we have to go into that cold sea. That morning the battalion loaded onto two LST's and spent the day at anchor in the harbor. Accommodations on these ships were far better than those on the transport. There weren't enough bunks to go around but the men slept in shifts and some made "beds" in the trucks. I recall hanging around the ship's galley and "bumming" a piece of sheet-cake or whatever else the "chef" was willing to hand out. Again, I avoided becoming sea-sick. On 3 December, the LST left Portland Harbor and crossing the English Channel, arrived at the mouth of the Seine River in the evening. The water was very rough but only a few of the men became sea-sick this time. Anxiety was taking over. The ship would ride up on the huge waves and then come crashing down, throwing the cold salty spray everywhere. If one would stand at one end of the "tank deck" and watch the overhead, you could see the ship bend and twist with the force of the beating that the sea was giving it. They say that an LST will go all the way over at more than 35 degrees roll. Well, at one point, we had a 34 1/2 degree roll. Everything was tossed to one side of the ship. I was on the outside deck at the time. Luckily I wasn't near an open area, I probably would have wound up in the water. This was quite a scare. The ship anchored about five or so miles off Le Harve and tossed violently in the rough water all night. Next day, 4th, we cruised back and forth off the mouth of the Seine River all day waiting to merge into an endless column of LST's, Liberty ships and merchantmen waiting their turn to enter the river. We started up the Seine in late afternoon, one ship in an endless column reminding me of circus elephants walking along, each holding the tail of the one in front. Sometime after dark we anchored upstream for the night. By this time in the war, the Allied Air Forces had rendered the Luftwaffe ineffective, otherwise an operation like this would be in extreme jeopardy. On the way, we saw for the first time, some of the destruction that the war had brought to France. Destroyed harbor facilities, bomb pocked concrete gun emplacements, sunken ships, etc. I couldn't help but think, "what was I getting into?" It wasn't over yet. 5th December, we arrived in the area of Ruoen and waited our turn to

beach the ship and unload. At about 1500 we drove off the ship directly onto

the beach and proceeded to a bivouac

area in the field a few miles from town. The weather was cold and not at all

pleasant. On the 6th, Headquarters, A and B Batteries waited in the bivouac area all day while the remainder of the battalion (on another LST) unloaded at Rouen and joined us in the afternoon. The remainder of the 422nd Combat Team lined up in the prescribed order of march, on the road ahead and behind us, to spend the night. We broke camp early on the morning of 7 December and proceeded to a bivouac area near Roselle, Belgium, arriving late in the evening. The route was via Amiens, Cambrai and Maubeuge. There were many bomb craters and much wrecked German war material along the route, evidence of a difficult retreat from France the previous summer. The 8th of December we marched (drove) from Roselle to St. Vith, Belgium arriving early in the afternoon. Parked on a hill, just east of town, we ate lunch and soon got orders to move into a bivouac area near Wallerode. It seemed to be very peaceful with only the occasional sound of an artillery round exploding somewhere way off in the distance. It was very cold and the snow was quite deep. Our initial task was to relieve the 2nd Div. on the Schnee Eifel, a "quiet" front about 27 miles wide. Pretty thin for one division, but then, nothing was happening here, (they told us). It was to be easy to trade places with the 2nd Division units. 9 December 1944, the battalion moved into the line east of the town of Laudesfeld and about one and a half miles west of Auw, Germany. The 589th FABn took over the positions of the 15th FABn. The Battalion command post was set up in the kitchen of a substantial German house. The firing batteries took over the dugouts and log huts vacated by the men of the 15th FABn. The howitzers were put into the same emplacements dug by the 15th and in some cases they were simply swapped since it was easier than trying to extricate the pieces already in place. "A" battery was placed on the south side of the road to Auw and "B" and "C" batteries on the north side. There was much snow here and the drivers were having big problems once they left the hard road. Service Battery was sent into a position a few miles to the rear, about four miles south of Shonberg, Belgium. The veterans of the 2nd Division assured their successors that they were in a very quiet sector where nothing ever happened. They hated to leave and when the 589th men saw what relatively comfortable quarters the 2nd's men were leaving they could understand that. We had been prepared to pitch puptents. Things were looking up. By 1630 registration was completed by "A" Battery and the battalion fired harassing fire that night. We were feeling rather secure. After all, our infantry was between us and the Germans. It sounded good to me. Because of all the work that the men of the 15th FABn had done and placing our gun in the exact spot that they had used, we had very little work to do. We used the same foxholes that they had dug. They had also built a small log cabin. This we used to get warm and sleep in. In a position like this, every member of the gun crew had to stand guard duty at night. This included me and the Sgt. I will tell you, that first night was very nerve racking. Not knowing very much about the situation or from what direction the enemy might come from, every sound was a cause for concern. Two hours felt like eight. The severe cold made it even more difficult. December 10 to 15 - The 422nd Infantry Regiment, which the 589th FABn was supporting, was occupying the first belt of pillboxes of The Siegfried Line which had been cracked at this point the previous fall. The Germans were well dug in opposite the 422nd in pillboxes and held other defensive positions in the area of the Schnee-Eifel, a wooded ridge about 3 miles to the front. The enemy communications center for this area was Prum which was at maximum range (12,000 yards) for "A" Battery. During this period there was little activity other than a few patrol actions. Few observed missions were fired due to the poor visibility. The battalion did, however, have a substantial unobserved, harassing program which was fired every night. The forward observer adjusted by sound, using high angle fire, which made it necessary to re-dig the gun pits. Alternate positions were selected and surveyed by the survey officer and his party. There were some reports of enemy activity but nothing, apparently, more than routine truck and troop movements. Headquarters Battery crews reported being fired upon on the 15th and that night an enemy recon plane circled the area for an hour or more. Numerous flares were seen to the flanks of the battalion and an enemy patrol was reported to be in the area. At night, watching across the snow covered fields, one's eyes tend to play tricks. On more than one occasion an outpost guard would fire away at some movement out in front of him, only to find out in the morning that he had "killed" a tree stump or boulder. Early in the morning, before dawn, at 0605, on 16 Dec. our position came under a barrage of German artillery fire. I was at breakfast in a quite nice log cabin. I had a good plate of pancakes and strawberry jam. The shells were hitting the trees. Shell fragments and tree limbs were falling all over the place. The official thing to do under these conditions was to get back to the gun. It wasn't easy, trying not to get hit with anything that would wound or kill you. Little did I know at that time, that breakfast would be the last standard meal that I would have to eat for four and one half months. During the shelling, many rounds exploded real close and showered dirt and tree limbs about, but also there were quite a few duds that only smacked into the ground. Those were the "good" ones as far as I was concerned. After about 30 minutes the shelling ceased. I did not have the foggiest notion what was going on except that we were under attack and things were becoming serious. (Frank Aspinwall reported in his book that from an inspection of the fragments, somebody determined that the enemy was using 88mm, 105mm and 155mm guns. I can't imagine that anyone was actually concerned about that bit of trivia at the time.) Wire crews were sent out to repair the phone lines that were out. At about 0800 the battery positions again came under heavy artillery fire, and again no casualties were reported. At about 0900 communication was again established with Division and with the 422 Infantry Regiment. However the lines were soon shot out again by the enemy artillery and after 1300, the battalion was, for all practical purposes, isolated from it's supported regiment. The Battalion Communications Officer and his assistant Comm. O. went forward to the Infantry Regimental C.P. after 0900 and while returning were fired upon and the Comm. O. was wounded. He was brought in and later evacuated. At 0915 a report was received of enemy patrols in Auw. An observer from "C" Battery went forward to a position commanding a view of Auw and from there directed effective fire on the town until he was pinned down by small arms fire. "C" Battery was unable to bring guns to bear on Auw due to a high mask of trees between it and the target. At about 1030 a patrol was sent out, as additional security, to man defensive positions along the road from Auw. Since it was now apparent that the enemy held Auw, an attack from that direction was expected. This patrol soon reported small arms fire from enemy infantry moving out of Auw. An O.P. was set up in the attic of a building being used as quarters for part of Headquarters Battery. At about 1500 three enemy tanks were seen coming along the road from Auw toward the battalion command post. At about 400 yards range the lead tank opened fire on one of our outposts damaging three machine guns. Small arms fire was directed against the tank, but it just "buttoned up" and kept coming. The lead tank now came into view of "A" Battery. With the way that the battery was situated, my gun crew was the only one that could get a shot at it. The tank was riding on the road from Auw to Bleialf. We were located about 50 yards lower than he was and on his left. Before we could get a shot at him there were four GI's running down the hill towards our position. I had to get in front of our gun and signal them to lay down which they did. I now tracked the tank and missed with my first shot. Immediately reloading and firing, I hit it this time. I fired and hit him again and it burst into flames. The enemy crew bailed out and was killed by small arms fire. The second and third tanks also took hits but were able to withdraw to defiladed positions. One of the tanks kept up harassing fire from a hull down position but counter fire was directed at it, and it is believed that it too was knocked out. The effective work of a patrol and our firing batteries kept the whole battalion position from being overrun that afternoon. The 2nd Battalion of the 423rd Regiment, in division reserve, was ordered to hold positions in front of the 589th while it withdrew to the rear. ("Strategic Withdrawal" they call it.) Meanwhile, the 589th held on in the face of heavy small arms and machine gun fire until the infantry was able to move into position shortly after midnight. Anticipating a move, a recon party had been sent to select positions for a relocation about 3 miles south of Schonberg, near Service Battery's position on the Belgian-German border. About 0400, on the morning of the 17th, the battalion was ordered to move out for the new position. By now the enemy was astride the only exit from the "C" Battery position so that it was unable to move. The Battalion C.O., Lt. Col. Kelly, and his Survey Officer, stayed behind and tried to get infantry support to help extricate this battery but they were not successful. The infantry had plenty of their own problems. "C" Battery never was able to move and was subsequently surrounded and all were taken prisoner, including the Battalion C.O., Col. Kelly, and the Survey Officer. Moving out of our position was not an easy task. The road that we came in on was made by 2nd Division engineers. They called it a corduroy road. It was a dirt path that the engineers had embedded railroad ties in. With the heavy trucks coming in and out with supplies the snow turned the dirt into mud. The mud now had become deep ruts. The big trucks churned the icy muck into a paste in which the guns sank almost hub deep. Hostile small arms and artillery fire was sweeping the area. Snow blew into sweating faces in the night. The wind howled through the trees, each of which might be hiding an infiltrating enemy soldier. All of the gun crews had to help all the guns and trucks pull and push until we had cleared the corduroy road. Not having any sleep that night and being covered with mud and snow, we were cold and bushed. Our new position was a field on the right side of the road that runs north from Bleialf to schonberg. We were about a mile and a quarter from Schonberg itself. We arrived with only three guns and went into our positions. During the night Sgt Alford's truck had run into the barrel of one of the howitzers and caused the radiator to start leaking. With the truck overheating, they had to lag behind. When they finally arrived, Lt. Wood held him on the road to act as anti-tank defense. Battalion HQ. commenced to set up it's C.P. in a farmhouse almost on the Belgium-Germany border, having arrived just before daylight. At about 0715 a call was received from Service Battery saying that they were under attack from enemy tanks and infantry and were surrounded. Shortly after that, the lines went out. Immediately after that a truck came up the road from the south and the driver reported enemy tanks not far behind. All communications went dead so a messenger was dispatched to tell "A and "B" Batteries to displace to St. Vith. Lt. Wood gave the order which in artillery terms is, "march order." He also made it clear that he meant "right now." Having been in this position for only about one and one half hours, we knew that the enemy was very close. I was waiting for our Sgt. to give the order, but I couldn't find him. Being second in command, I gave my men the order to pack up and be ready to move. I looked all over the area and just couldn't find my Sgt. Shook. The two other crews started to move, so I jumped in the truck and gave the order to go. I was now in command. Never knowing when something that bugs you turns out to be a good thing. Before we left the first position they asked that one of our men be assigned to the group that was leaving to search out the next position. This bugged me because that left me a man short for the tough job that we had in front of us. This turned out to be a blessing. He told me not to go out the way we came in. He knew an easy way out because he used it in checking out the position. One of the other crews followed us. We got out on the road and started racing for Schonberg. Our destination was as ordered, St. Vith. Sgt. Alford, who was already on the road, ditched his truck and hooked up to a supply truck and was right on our heels. At this time artillery shells and small arms fire could be heard all over the place. Sgt Scannapico, who was in charge of the fourth gun started to leave the area the same way that we came in. Before they reached the road, the truck got stuck. Lt. Wood, knowing this, stayed with that crew. They pushed and shoved like crazy until they got on the road. Our three guns got through Schonberg just in time. The Germans were now all over the place. Sgt. Scannapico along with Lt. Wood, had lost precious time. When they got to Schonberg they were met in the middle of the road by a German tank. Sgt. Scannapico jumped out of the truck and started firing at the tank. He was killed on the spot. The tank opened fire and had a direct hit on the truck, killing the driver. Lt. Wood and the rest of the crew bailed out of the truck and ran for the cover of a brook. With the infantry firing at them, the crew put their hands up and surrendered. Lt. Wood, leaping the ditch, ran, dodging bullets all the way, reached a tree line and disappeared. Even to this day, 50 years later, there is much controversy about what happened to Lt. Wood. I won't go into it here. I will, at the end of my story, add some articles about him.

The remainder of the battalion assembled again west of St. Vith where they were joined by Service Battery of the

590th FA Bn. They were ordered

into position north of St. Vith to establish a road block to protect the

town. Later, that night, they were withdrawn to a bivouac area in the vicinity

of St. Vith. December 18 - After this halt, orders were received from the Division Artillery Commander, General McMahon, to proceed to the west and be prepared to take up positions in the vicinity of Recht. The battalion was halted at 0100 and remained on the road until 0700 when it began moving forward again. At about 0800 the column was halted again and word passed down that enemy tanks and infantry had attacked HQ Battery, 106th Div. Arty. on the same road to the west. The column was turned and pulled off the road into a clearing. A perimeter defense was organized and a road block set up with two guns covering the approach from the north. A noon meal was served. Orders were next received to withdraw to the vicinity of Bovigny. What was left of the battalion loaded up and proceeded to the designated place in good order. The preceding night the Germans had dropped parachute troops into the area near St. Vith. They were not in great strength but they did a lot of shooting and spread confusion along the communications routes west of St. Vith. At Bovigny the C.O. of the 174th Field Artillery Group requested that the three howitzers remaining with the battalion and the personnel be sent to positions near Charan. This was agreed to and the battalion was split into two groups: Group A composed of the three 105 howitzer sections, Fire Direction Center people, most of the officers, and part of our meager ammunition supply. I was with this group. Group B was composed of the remainder of the battalion plus some men from the 590th Service Battery. Group A departed for Cortil, went into position and laid the guns to fire on Charan. The town was reconnoitered and no enemy was found so the group was withdrawn to Bovigny for the rest of the night. Observers were sent out with the outposts and preparations made to fire on any enemy coming on the scene. Group B left Bovigny and traveled west through Salmchateau and bivouacked for the night on a side road near Joubieval.

On 19 Dec 1944, in the afternoon, what was remaining of the 589th

FABn arrived at the crossroads at Baraque de Fraiture to establish some kind

of blocking force against the German advance. Whether or not there was any

intelligent planning involved in this move I really don't know. I had the

feeling that nobody knew anything and that we would resist here in this

place as long as possible and hope to get help before we were blown away.

There were approximately 100 men and three 105mm howitzers to set up the

defense at this time.

The weather was cold, wet and foggy with some snow already on the

ground. Visibility was variable, clearing from maybe fifty yards to two or

three hundred on occasion. I didn't even know who was in charge of the rag-tag group that I was with until I saw Major Elliot Goldstein out in the open, verbally bombasting the enemy (where ever they were) with all the curse words he could think of, and at the top of his booming voice. I thought at the moment that he won't be around too long if there are any Germans out there to hear him. Apparently there were none, he drew no fire. The three howitzers were ordered into position to defend the crossroads. This was no longer a firing battery position. Each gun was placed at a strategic position covering all the directions that the enemy may come from. I never saw any of the other gun crews again. My gun was placed on the crossroad proper. The gun was facing east, towards the town of Regne. Across the street from me was a farm house and a barn. After getting the gun in place and digging fox holes, I walked across to the barn. To my surprise there were a few GI's already in there and they were talking to an elderly man in French. I asked them what he was saying. They told me that he was the owner of the property. I then went into the house that had been taken over by some cooks, although they never cooked anything that I know of anyway. Also a first aid station was set up. A fire had been started in the stove and the heat felt really good. For the remainder of the time that we were there, one half of the crew were permitted periodically to go over and get warm and have a cup of coffee. Next morning, 20 December, the weather remained miserable, cold, wet, and some more snow for good measure. Hearing the squeaky sounds of tank treads coming toward you is a very frightening sound, especially at night. However, it was daytime and I was very happy to see that it was one of ours. He then pulled around the corner and parked right in front of the farmhouse. The men in the tank jumped out and waved, "hello." One of them walked up to the corner and looked down the road in the direction that my gun was pointing. One minute later he fell to the ground with a bullet between the eyes. Captain Brown, who was now in charge of the three guns, having witnessed this came running over to me and ordered three rounds fired into the trees down the road. It had to be a sniper. We never heard any more from that direction. I have thought about that ever since. This man was just across the road from me. How come he never fired at me? Thank God he didn't. I can only rationalize it like this. I always had a helmet on, he didn't. We were partially concealed under a tree line, and he was out in the open, or, he (the sniper) had only just arrived at that time. About a couple of hundred yards from the crossroads, my good friend, John Schaffner and another man from B Battery, Ken Sewell, were in their foxhole as forward observers. Around midnight they heard strange noises in the fog. It was very dark and the visibility was extremely limited. When they were able to discern what was making the strange noise, it was about a dozen Germans on bicycles. They stopped in the road when they came upon the daisy chain of mines that had been strung across the road. Being unaware of John's presence, not 10 yards away, they stood there in front of them. The Germans were talking over what to do next. John could tell that the language was not English. They also had on square helmets. John and his companion were in big trouble. He whispered the situation over the telephone to Captain brown. Captain Brown told him to keep your heads down and when you hear me fire my .45 the first time, we will sweep the road with all we got. When that stops I'll fire my .45 again, then we will hold fire until you two can return to the C.P. MAKE IT QUICK! The word was passed around to all the people on the crossroads. We took up positions with carbine in hand and on command from Captain Brown, everyone let loose with all the fire power available. I was lying next to a quad multiple .50's machine gun. The sound was deafening. On command we stopped firing. At first there was complete silence. Then for the rest of the night all you could hear were men crying and moaning with pain. The records say it was an eighty man patrol, however John says he only saw around twelve. The next day, 21 December, a detail was sent out to have a look around, John Schaffner reports that they found several dead Germans in the snow, no live ones. The enemy apparently pulled back and took their wounded with them. During the morning hours enemy tanks were reported as being in Samree. The town of Samree was to the southwest of us. My gun was pointing northeast. Major Parker came over and told me to turn the gun around 180 degrees. We had to move it around until we found an opening in the trees where we could fire in that direction. Captain Brown and Major Parker with their maps and good math, figured out the elevation, direction and powder bags to be used. The only line of sight we had was the roof line of a house. Captain Brown then told me to come as close to the roof line as possible without hitting it. I lined up in my sight but was still not sure. I then had to look through the bore of the tube. Keeping my fingers crossed we loaded a shell and I said, "OK, FIRE!" Luckily, we missed the house. We then fired three more rounds. I had no idea where those shells would land. Later on I found out that we did indeed send those tanks running for cover.

Later on that day two German prisoners were brought into the CP. John

Schaffner was detailed to guard them. One, an officer, spoke good English.

He warned them that the German Army was coming through us and would kill

anybody in the way, so we could save everybody a lot of trouble by

surrendering to him right then and there. Ha! Ha! To get a better picture of our situation at the crossroads, one must consider the situation. The krauts were swinging high, wide and handsome to the northwest from Houffalize. The 1st Army defensive line was consolidating slowly, the 82nd AB Div held what amounts to the last solid position on the Army right flank with the 3rd Armored on its right extending only a tenuous screen southwestward down to the Ourthe river.

That right flank of the 82nd just had to be hammered down tight,

protected from Hotton to Salmchateau. For the moment it was flapping in the

breeze and the crossroads was the sensitive point. Through it all Major Parker was everywhere, observing at the outposts, moving from place to place along the perimeter as one attack succeeded another. Wounded by a mortar shell in the afternoon while adjusting fire, he refused to be evacuated until he lost consciousness. Major Goldstein succeeded in command. Big mistake!!!

On Dec. 22 a patrol was sent out during the night to reconnoiter

enemy positions to the east and south. The patrol

reported the enemy digging in along the road to the east inside the woods. It was expected that the Germans would attack at about 0530. Artillery rounds from all three guns were fired to simulate a counter-attack. No German attack materialized. Around noon a company of the 325th Glider Infantry of the 82nd AB Div arrived. A few of them told us that we were safe now, they were going out in front of us to protect us. When the Germans decided to come at us, there wasn't anybody out there to stop them. Dec. 23rd During the early morning the enemy infiltrated

into the woods to the north and set up a line in front of the woods

running to the east-west road. At about 0430 an SS Offizier patrol attacked

from the south-east at the same time an

attack was made from east and north. All attacks were beaten off and an SS

lieutenant and a Sgt. were taken prisoner. Interrogation disclosed that the

2nd SS Panzer Division was

approaching from the south.

Even with the reinforcements of the infantry company it was apparent

that morning that a coordinated enemy attack

could not be withstood. So Major Goldstein left the crossroads with

the SS lieutenant and Sgt. He was going to try to convince the commander of

the 3rd Armored Division that he needed help. This is why I said, "Big

mistake." Major Parker had been ordered a few days earlier to withdraw and re-organize. He disobeyed those orders because he knew the importance of that corner. I feel that he would have never left, if he didn't get wounded, without taking his men with him. Major Goldstein, knowing that the situation is now hopeless, we are out of ammunition and medical supplies, he takes off. If he had of stayed, he would have realized that the order to withdraw was still in effect. We possibly might have been around to fight another day. At about 1530 in the afternoon all hell broke loose. Captain Brown came around and told us to be ready, when the artillery attack stopped, the infantry and tanks would be coming in. Half of my crew were in the house getting warm. I made a run for it to get my men back to the gun to be ready for the assault. Once inside, I got my men together, but we never did make it back to the gun. I was standing in the doorway ready to go when a shell hit. The concussion picked me up and sent me flying against the back wall. I sat there a few minutes in a daze. I had to feel for my legs and arms to make sure they were still there.

At about this same time the farmhouse itself was now being hit with incoming shells. The roof was on fire and some of

the fellows were trying to put the fire out. In this building there were

also some wounded men. Our main concern at this

point was, how are we going to help them. Our concern was soon ended.

The shelling stopped and at the same time there was a German tank outside

the door. His gun was pointing in the door. A German officer shouted out,

"Are you coming out or do I tell this guy to fire?" No one can be

a hero when a tank is staring

down your throat. Some of the surrounding area men had already been rounded up and were standing in rows on the road. We filed out of the building and joined the rows of men. They made us remove our overcoats so they could search us. They took anything of value. I was wearing my wife's (although not at that time) high school ring. That was gone. The other items were money, cigarettes and chocolate (every GI had a few concentrated chocolate bars called "D-Bars", that didn't melt. They were hard and you had to scrape off shreds, or if you had good teeth you could break off a chunk), my gloves, my wool knit cap and my fountain pen. For some reason they would not take wedding rings. Either they were superstitious or they had some respectability. It was now approximately 5:50 PM. The weather was bitter cold, but now I had no overcoat, gloves or wool knit cap. It was a cold helmet and field jacket from here on. How I made that winter with just those clothes I'll never know. The following are the words of Col. Dupuy for the Infantry Journal Press, and that's the story of Parker's Crossroads (named for Major Parker and to this day is known as Parker's Crossroads) and the three piece 589th Field Artillery Battalion, the end of the trail for the three howitzers of Battery "A" which Eric Wood had gotten out of the Schnee Eifel. It is a story for American artillerymen to cherish along with the saga of O'Brien's guns at Buena Vista."

One cannot help wondering what would otherwise have happened to the

thinly spread 82nd Airborne Division's right flank as the 2nd SS Panzer

Division moved in for the kill. After fifty years it is impossible for me to retrace my route of march as a P.O.W. I didn't know it then, we had no idea of where we were or where we were going. I can only reflect back on some of the events that happened. On the road at Parker's Crossroads were assembled approximately fifty men. After they completed the search, we were marched off in the direction of Prum, Germany. we walked for about three hours and were put into a big mill. This was the start of what was to be our way of life for a long time. No roof, windows or beds. Pick a spot on the floor, sometimes wood, sometimes dirt, lay down and go to sleep. Everyone was exhausted, hungry and cold. With the cold and being hungry, I still was able to sleep. It was probably the first real sleep that I had had for almost a week. The next morning, to our surprise, the combat troops that marched us here were gone and we were now being guarded by a rag-tag looking bunch in their fifties and sixties, appearing ancient to us who were half their age. The great equalizer was the weapons in their hands. We were then given a slice of dark brown bread (which I was told is made out of sawdust as a good part of the ingredients) and a piece of sausage type meat. It was approximately 1 & 1/2 inches in diameter and 2 inches long. Not knowing when I had anything to eat last, this was pretty good. I didn't know at the time this had to last you until tomorrow. We then started to march toward the town of Gerolstein, Germany. How long it took I don't remember, but every day was the same. We stayed in some bombed out building at night and marched out the next day. We now have expanded our group to approximately 150. It was becoming harder and harder to find a good spot in the building at night to sleep. Space was becoming smaller all the time. Even the slice of bread was thinner and the length of meat was shorter. Along this route we encountered another one of our near death

experiences, which we will run into many times in the future. Off in the

distance we could see some of our own fighter planes. They would circle

around until they were ninety degrees to our line of march. Then they would

come at us from the side with their guns a-blazing. When in the distance they

saw a column of soldiers marching down a road in Germany, they would assume

they were Germans. We were told not to run, but to start waving and holding

up your helmet or overcoat and

wave like crazy. After the first few planes flew

over they would radio back and the rest would not fire. Now they

would circle around and come down the road right at you. They would be at

tree top level as they went by. They would dip their wings from side to

side, we could see the pilot and he would wave at us with a gesture like,

"Gee, I'm sorry." Needless

to say, some helpless GI's were killed and wounded. Walking wounded we could

help, seriously wounded had to be left

there. I never knew what happened to them, my guess is they were shot. The

enemy had enough problems taking care of all the P.O.W.'s

They had no time or facilities to care for the dying. I finally arrived at Gerolstein. This was a small town, however it was a major railroad center. Again it was a big mill of some kind. It must have been a storage facility. It had a cement floor and large storage bins from floor to ceiling up the walls. If you were lucky you could get into one of the bins. Each one could hold three guys. It was much better than sleeping on the cold concrete and they were warmer. It now began to sink into our minds that the future was going to be horrible. I pictured in my mind that we would be placed in a camp some place with barracks and beds, mattress and blankets, regular meals and a place for exercise. What we got was cold, dirty, bombed out mills. Hundreds of men crammed into a space that is too small. The mood of the GI's was now starting to get ugly. Many things contribute to this. Being hungry and cold, and now a new problem started to develop, dysentery. In these buildings there were no bathroom facilities. You had to go outside in a big pit that had been dug for that purpose. It doesn't take much thinking to picture climbing down from one of the bins in the dark, trying not to step one someone sleeping on the floor, to get outside. forget that most of the men did not make it. Soiling yourself was now a big problem. You had to go outside, take off your under pants and outer garments, often including your shoes and socks, turn them inside out and try to wash them out with snow. Picture what happens now, putting on all the wet clothes and freezing to death until they dried up. The first food offered was a beverage, delivered in old wooden tubs that looked like those our grandmother used to boil clothes in. The German equivalent of coffee was our first experience with "ersatz." While it looked good and was hot, the appearance of being coffee was all that it offered. The brew came from an unidentified burnt grain that developed color and some indescribable flavor. Because it was hot, often times it was used for shaving. I say shaving. It was more like torture. Who ever had a razor, with only one blade, would pass it around. I'll bet there had been 500 shaves on that one blade, it only pulled the whiskers out. The soup in those old tubs was not a proper term for the concoction created out of rotten potatoes, turnips and pine needles. The nourishment was negligible and the flavor and texture repugnant. Though most of us had never before eaten such bad fare, we managed to get it down. Some men just could not eat it at all. These poor souls vomited when their stomachs refused to accept this offensive food. What little nourishment offered was lost to many of these men who were either unable to swallow the swill or to keep it in their system. Their physical condition deteriorated rapidly. All of us were eating our own bodies. One day we would get the soup. It would be delivered to the building in the old tubs. Two men would be assigned to dish it out. Each man thrust his eating utensil, helmet, canteen cup or other container at the man you hoped would be your friend and give you a little more. This never happened, no matter how big your container was. One ladle per person. Now the cry was to get that ladle down to the bottom of the pot. This way you may get some of the stock and not all water. The ones that had to use their helmet were in trouble. Don't forget that his helmet had many uses along the way and eating out of it was only one. I was lucky enough to have picked up a clean tin can along the way and this became one of my prized possessions. The next day it would be a slice of bread and a small piece of the sausage type meat. The meat wasn't a too bad tasting fare. This however is another matter. The German army developed the bread reputed to last for months without becoming moldy or stale, no matter what climate or storage facility. Whether German troops ever ate this ration or if it was purely a Stalag food, I never did find out. This dung colored bread with the texture and taste of dry sawdust was to be our primary solid provision for the next four months.

Usually a loaf of bread (about the size of a standard loaf of our bread) was divided between six men. If a new group of

men came in that day, it would be seven men. To cut a loaf of

bread into six or seven equal pieces is an impossible task. The cries

of inequality soon created systems designed to eliminate favoritism. Each

day a different man was selected to cut the bread. The cutter got last

choice. One group cut cards to establish the order of selection while others

simply rotated the order. The process of cutting the loaf, the portion selection process and the pitifully meager meal became the highlight of the day. Table conversation did not exist. Each man took his ration to as private a corner as he could find to relish the taste and texture of this wretched food with no distractions. The sight of strong young men wetting a finger tip to pick up bread crumbs from the floor gave mute evidence to the degrading power of desperate hunger. Someone broke into a storage shed and stole some onions. To find the culprits the Germans announced that they were poisonous gladioli bulbs. Apparently the perpetrators chose death before punishment as they were never found. Every morning around 07:30 and every afternoon around 5:00 PM we had to assemble in the courtyard for roll call. The irritating German Funf mann (five man) counting system was the standard every where we went. During our captivity we would be counted hundreds of times. The process never varied. It involved lining up in a column of five abreast. Two guards moved down the column counting by fives. The German soldier, we would discover, as with many other tasks, made a real project out of what should be a very simple process. They often lost count and had to start over. This incessant counting was a constant irritation. Of course, I can't blame it all on them. Our group would help them get a different count from each other. When the first guard passed, some of the guys would step up after they were counted and make a new line, so the one guard would always come out with five more than the other guard. So, they would start again, over and over until they got mad and then you stayed in line. After roll call they then would ask for volunteers to go on a work detail. If they got as many as they needed the rest would go back into the building. When they didn't get volunteers they would count off as many as they needed. Some times you would go two or three days in a row. Believe it or not, some people would volunteer, if that day you didn't feel too sick or weak, it was better than sitting around in the cold building. The work that had to be done was clearing the debris off the roads or railroad tracks after the bombing. Then fill in the craters with dirt. One time all I had to do was chip the mortar off bricks, then stack them up. One day a fellow in my outfit, Charlie Jacelon, and I went out on the same detail. While we were at work about one hundred B-17 planes came overhead. This caused the guards to take cover. We also started for cover. Charlie and I went into the bombed out cellar of a home. We then went scrounging around . Much to our surprise we found two jars of something that the family had canned. Now, the trick was to get them back to the compound without anyone seeing them. The only way to do it was to take off your field jacket and roll the jar in it. This we did, and we must have looked crazy on a bitter cold day, two guys walking back into the area with no coat on. We waited until everyone was asleep before we opened the gift from heaven. To this day I don't know what it was, but it was good. It was like Christmas eve, opening your presents. I did mention that Gerolstein was a major railroad center. The reason that so many men were brought to this compound was that they would collect a train load and then ship them further into Germany. Now it came to be my turn to be moved on. When they had enough men for a train load, you went. How they determined who went and who stayed, I don't know. I went and Charlie stayed. There were about five hundred in the line of march. We were loaded into old 40 & 8 style boxcars. Sixty men to a car. These boxcars are much smaller than the ones in the U.S.A. There were two small windows high on each side near the end of the car. The windows were covered with barbed wire. There was a metal can for our facility. It was the size of a five gallon can. The sanitary conditions, using the can, was terrible. many of us had diarrhea. We could not all lie down to rest or sleep at the same time. We slept in shifts and when you did get settled down, someone would have to run for the can. Usually there was someone over it. It caused a lot of problems since a man with diarrhea has little "holding power." The stench was terrible.

I was in this boxcar for two days and we never moved. The tracks up ahead had been bombed after we got into the

boxcars. The doors were jerked open by armed guards who screamed what seemed

like threats of terrible retribution if we did not

move. "Raus schnell!!" (Out, quickly!!) Our legs had a hard

time holding us up because of the cold and the lack of

movement in our cramped quarters. We were filthy. Uniforms were

fouled from the dirt of the battlefield and our own or

someone else's excrement. Everyone looked confused and bone-weary

from the lack of sleep and food. If there was any

military discipline left in us, the abuse to our bodies had buried it

under the the pressure of survival of the fittest. We no longer looked like