|

William Devine |

|

|

|

|

|

In any event, after thirty years of reliving the nightmare which has been indelibly stamped on my mind, and still suffering for those who were not as lucky as I was, I decided to write this account and dedicate it to the 106th Infantry Division. In so doing I am not discounting the tremendous valor and sacrifices of all the other branches of the Armed Services who made this final stand possible. They were in it from the beginning and suffered the hardships of war for a very long period of time. ----------------------------- This is also being written by an angry man. The "War to End All Wars" turned into a farce. How many of our wonderful young men have been killed and wounded in the wars that have followed, and how many more will share the same fate if the madness which has gripped the world does not cease? I do not have the answer, but I do know it had better be resolved soon!

My wife and I stared at each other in

disbelief. It couldn't be happening, but it was! I was thirty-seven

years old, weighed almost three hundred pounds, with feet that had

to be flat carrying all that weight, and my normally high blood

pressure was rising every second. Yet I had passed the "physical"

with flying colors and my Greetings from the President was in my

hands. Due to unfortunate circumstances my wife and I had no

children after almost ten years of marriage, and this was no doubt a

contributing factor in my being drafted; but in my condition they

were really scraping the bottom of the barrel. World War II was well

into its third year as far as the United States was involved, and we

had lost many men by that time. Unlike many others in my position, I did nothing to try to have my status changed, being proud to be an American and knowing that I could not live with myself if I "welched." Remember, this was the "War to End All Wars", much different than the ones to follow, and so I accepted my fate without protest but with a very heavy heart.

It was on March 7, 1943 -- I will never forget that morning -- leaving my wife and everyone, who meant so much to me. I was the only draftee to leave from my district that morning and it was a very lonesome trip down to the Pennsylvania Station in New York City. Down there I met hundreds of other men in the same frame of mind as mine, all feeling very sorry for ourselves.

However, it was not long before things started to happen. First we were put in squad formation (four abreast) by a corporal who had probably been drafted a month before I was, but the way he showed his rank you would think he had twenty years of service behind him. But, after a couple of hours one got used to all the "ninety day wonders." We were marched in formation to the train en route to Fort Dix, New Jersey. This train was of the 1920 vintage - all wooden cars and the old church pew seats that were mighty hard on the fanny. Before long a huge M.P. sergeant appeared, shouting like a barker, and informed us what we could and could not have nor do. It made us feel like we were prisoners sentenced for a long term.

After three hours we reached Fort Dix in the middle of a blinding snow storm, and immediately started being what they called "Processed," but I called it hardened. At about one p.m. we started collecting our equipment and by twelve that night (without a stop) were completely outfitted in every detail. Thus ended the first step of becoming a G.I.

We were assigned to barracks to await our orders, and on the fifth day were told to prepare to leave, but our destination was not divulged to us. About six hundred of us were marched down to the railroad siding and hustled onto a train which fortunately was more modern than the first one. We rode all day and night, still wondering where we were we would arrive at Fort Jackson, South Carolina. This was one of the largest induction centers in the United States. We were met by the post band and about fifty trucks to drive us to the fort. The heavy underwear that we had enjoyed wearing in the snow at Fort Dix was not appropriate for this warm climate and we found ourselves wet with perspiration. After showering and changing to lightweight uniforms we were examined by the post doctors and then taken to our assigned mess halls. The food was great - so different than we had been getting we felt as if we were at West Point. We had to wait a couple of weeks for more men to be shipped in before starting basic training, and were informed that we were to be trained as the 423rd Infantry Regiment which was to be part of the newly activated 106th Division. Basic training, we were told, would be as bad, if not worse, than actual warfare -- and after going through it I heartily agreed. The days in Fort Jackson were very hard on me, as I was put in an experimental division with all young men of ages from eighteen to twenty and was considered an "old man" at my age of thirty-seven. This was how I came to be called "Pop" or, more frequently, "Father Devine.” My duty in the 423rd was in the capacity of Supply Clerk in the Service Company. When it was my turn to act as orderly for twenty-four hours in the Captain's office, one of my duties was to awaken everyone at five a.m. This was not as easy as It seemed, and required prudent action.

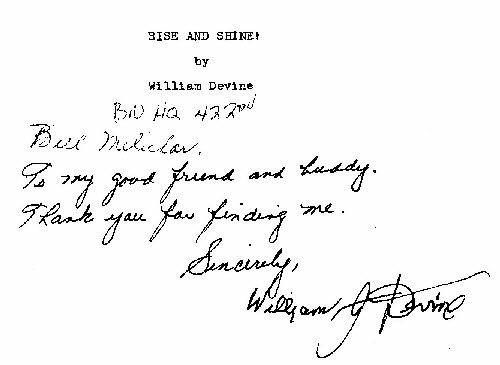

I would turn on the downstairs lights in the barracks and go upstairs yelling in my loud sonorous voice, "RISE AND SHINE WITH FATHER DEVINE" Then I'd run downstairs as fast as I could, yelling the same thing. Being able to go downstairs a lot faster than up the stairs I managed to dodge a lot of things that were thrown at me. I maintained the title of "Father Devine" all through Europe and until the day I was discharged from the Army.

My first experience in basic training was a tour of maneuvers in the scrub pines of South Carolina. Between watching out for the snakes, which were numerous, and the "jiggers" whose bite was worse than any other insect I've known, we were mighty uncomfortable on that sandy terrain. We had to sleep on the ground In a shelter half, rain 'or shine, and sometimes we would have just turned in for the night when we'd be alerted to move out. After packing as fast as we could we'd get moving on the road, traveling for many miles before we were allowed to stop for a rest. This was dust a part of the hardening program to help us combat all kinds of fatigue and disease we would possibly have to face. The games would last about ten days or more at a time and we experienced hardships equal to real warfare, perhaps even harder. It was not easy for me to keep up with eighteen and twenty year-olds during basic training, and I was always trailing behind them. Crawling under barbed wire on my still expanded belly was very difficult, but I managed to do it. The foxholes were especially a problem; they were always too small for my huge frame and a part of me always stuck out. The boys would often have to push me down when I couldn't squeeze all the way into the foxhole.

Although at the time I did not realize it, this was probably the best thing for me psychologically. I was so exhausted at the end of each day I fell into a sound sleep as soon as my head hit the pillow, and this kept me from thinking too much of being separated from my beloved wife, Dorothy. Our married life had been complete in every way and this was the first time we had ever been apart. After about eight months in Fort Jackson we were pretty much ready for something bigger in the way of war maneuvers. So during the early part of January 1944 we were alerted to move to the mountains of Tennessee for the winter maneuvers, and after traveling for two days arrived there for our first bivouac. This was to be our last test of endurance before we shipped overseas. I can recall the first night there, because it was so unusual, weather wise. I made a bunk for myself on top of a lot of cases of supplies. When I went to bed it was clear and very beautiful, and when I awakened I was covered with snow. I never experienced anything worse than the hardships we suffered during those maneuvers. Yet, while they were almost unbearable they were to save my life in the months of hell to come.

An incident worth mentioning occurred in one of the bivouac areas where we stayed for a day and a night. We had been on the move for about twenty hours without sleep and finally came to the ruins of an old outpost fort where the church and graveyard were still intact. It must have been at least a hundred and fifty to two hundred years old and this was all that was left of a pioneer settlement. On the front of the church was a plaque telling of the massacre that took place in the late 1700*s, and many of the tombstones bore a short story of what had happened to the entire garrison at the fort.

That night one of the eeriest experiences of my life happened to me. I was standing guard duty from twelve midnight until two a. m, on the edge of the bivouac area which overlooked the surrounding territory of open field and was bathed In moonlight. Perhaps it was because a great impression In reading of the bloody massacre by the Indians had affected me, or perhaps I was overtired and hallucinating; but for two hours as I looked out over the field I could swear that I was actually there at the time of the massacre over two hundred years ago,, reliving all that happened. I seemed to be in a state of suspended animation, unable to move, but so help me God, I could see the whole massacre taking place; the Indians killing the soldiers and settlers, the dead and wounded being brought into the tort, and feeling the horror of it all. This time lapse lasted for almost two hours and was so real to me that when I was relieved at two a.m. I asked some of the other soldiers if they had noticed anything strange about the place, and some of them said they felt as if they were going back In history for many years.

I have tried to convince myself that this was a figment of my imagination, but was it? I wish I knew the exact location of this historic site because I would like to revisit its but we were moved out early in the morning and I never had a chance to collect more tangible information, However, I have heard of similar cases experienced by other soldiers.

Another tough day lay ahead of us. After breaking camp early in the morning we traveled all day through the mountains. We couldn't stop until we found a place which was accessible for trucks and equipment, and in these mountains they were mighty scarce. Finally, by night, we found the right spot. It had been raining all day, so by this time we were very wet and cold. When it rains in the Tennessee mountains it is like nothing you have ever experienced. By now the temperature was below freezing. We could not sleep on the ground because it was flooded and frozen, so we slept in the trucks. I should say we tried to sleep but it was Impossible as we were soaked to the skin and shaking with the cold. Even lighting candles didn't help. Luckily for us the commanding officer, in making his tour of inspection for the night, saw the condition we were in and told us to get out of the truck and go over to a crater near our bivouac area. It must have been made by a falling meteor long ago as it was certainly not man-made. We were instructed to gather all the dead logs we could find and pile them in the middle of the crater, then pour on gasoline and start a fire. We draped the shelter-halfs over our bodies, forming a tent-like shelter, stood up with our arms around each other's shoulders in a circle about ten feet away from the fire, and tried to keep from sleeping. However, we all dozed off from time to time for a few minutes, leaning on the next man. This went on for several hours until daybreak. We can thank the commanding officer for saving us from pneumonia, frostbite, or worse; and we gave credit to all the shots we received in the beginning, which we griped at, for saving our lives.

After standing up all night we had to move out after breakfast. Although this was almost the end of the maneuvers we were to experience another traumatic incident. Upon reaching our final destination, or the wind-up of the maneuvers, a sergeant and I were instructed to go out on laundry detail. This meant taking the laundry of everyone in the RSO (Regimental Supply) to the nearest mobile laundry, wait for It to be finished, and return as quickly as possible, because we were to go on furlough from this location. We started out on a beautiful morning at about seven o'clock, not quite sure of where the laundry was, but we finally found it after three hours even though it was only fifty miles away. Another three hours elapsed before the wash was finished, and as we started back to camp it started to rain. By the time we reached our bivouac area it had turned into a torrential downpour and a flash flood which washed away everything that was movable. All we managed to save were our duffle bags. Thus ended the maneuvers, and we all felt we couldn't have taken another day of them. After a wonderful two-week furlough at home, we reported to Camp Atterbury, Indiana (April 1944) and remained there for about five months on another training program. Then we were moved to Camp Miles Standish in Massachusetts for two weeks, and finally to New York to be shipped overseas. When we reached New Jersey we boarded a ferry boat to take us to Pier 86 North River, New York, where we were to board the Queen Elizabeth for our overseas trip.

While on the ferry we stayed on the outside deck, sitting on our duffle bags, and we were all quiet and depressed. I, for one, was within about five miles of my home and could not see or even call my wife to say goodbye. But invariably there is always something to give us a lift whenever we're down. There were some G.I.'s who had never seen a large body of water before, and had actually never been in anything larger than a rowboat. As we were crossing the Hudson River to Pier 86 an officer in back of us was wide-eyed at the sights of the New York harbor. When he said to another officer "Captain, it's sure going to take us a hell of a long time to get overseas on this thing" we all forgot our troubles momentarily and had a good laugh. I know he was serious because he was from the deep South and admitted to never having seen a big boat nor such a large body of water.

Upon embarking on the "Queen" we were assigned to our staterooms, and I can honestly say that they were the same as when the civilians used them, with the exception of some of the furnishings. Instead of beds there were upper and lower bunks which were not bad, and beautiful bathrooms with hot and cold showers.

After getting all the "do's and don'ts" from the captain in charge of our section we bedded down, and next morning we awakened just in time to wave goodbye to the Statue of Liberty. It was an exciting trip because we traveled without an escort, due to the fact that the "Queen" always sailed alone. Because of her great speed she was too fast for a convoy and went in a zigzag fashion so the German subs could not get a shot at her, and she succeeded throughout the entire war without getting hit! The trip took about ten days because of this manner of travel, for safety reasons, but in order to keep up our morale we were constantly kept busy with movies, games, and various other activities.

At last we arrived at our first European port, which was Scotland, and when we saw the coastline with its beauty and historic castles It was easy to understand why people raved about its romantic history. When the landing craft appeared alongside we had no trouble boarding it through the lower deck. Upon landing on the beach we were marched to the railroad station where we had our first look at a foreign coach train. The cars were composed of compartments to accommodate six people, but eight of us with all our equipment were crowded into each one, and this was not too comfortable an arrangement.

We traveled for two days, stopping every now and then at different towns where we were able to buy fresh food from the townspeople who came down to the station to sell it. This was a welcome relief from our usual rations, as the people pre. pared the food in their own farmhouses. They would be informed ahead of time of our arrival at their stop and were there to greet us with all kinds of hard bread, pastry and fresh hot meat pies which were delicious. The townspeople made a nice income from the American G.I.'s, as we were ignorant of the exchange value and paid them in U.S. currency, thereby always giving them more than they asked.

We finally found ourselves riding through the English countryside, which was beautiful farmland country. Cheshire was our destination, and we were told this was the birthplace of the steeplechase races and the home of the retired military. When we arrived there at midnight in the rain and cold there were no trucks to meet us this time, and we had to march to our barracks which were about eight miles away and all upgrade. We carried our rifles and full pack weighing about seventy pounds. I kept up with the kids as long as I could, but halfway up I had to drop out and wait for the end of the line, which gave me time to regain my strength and continue on.

Some of the 423rd Regiment were bivouaced on the old steeplechase track. Being in the Regimental Supply I had to deliver food rations for the whole regiment, which involved going to every mess hall, some of which were quite far away from the RSO. My detail and I would be up most of the night delivering rations for the next day. We were billeted in Quonset huts which had been left there by the last G.I. outfit. They weren't too bad, each one having a big bellystove which gave out wonderful heat.

As soon as we were organized we set up a Post Exchange at the end of our compound. It was supervised by a handsome, blond young fellow who had been in show business and was the best thing that could have happened to us. He had a way of acting "cute", as the fellows said, and some of them were a little shy at the way he acted at times, but he was never offensive and I'm sure it was just his way of exhibiting his many talents. He was a professional adagio dancer, and a good one at that. Much credit must be given to him for keeping up the morale of the ESO detail, which comprised about fifteen of us. I can remember coming in from a hard day delivering rations in the rain. George would see how depressed we were and without hesitation would start a one-man show by himself. He would sing, dance, and make funny remarks to us about our manly stature. In a few minutes he would have everyone in the hut yelling and laughing, and this would last until bedtime, after which everyone went to sleep In a happy frame of mind thanks to George. We could never thank this young fellow enough for his efforts in helping to make life more pleasant for us.

Once he traveled a long way to pick up a half barrel of good old English ale which he arranged to sell at the P. X. We were to bring our canteen cups with us and buy by the cup. George needed a bartender, and I happened to be available. Well, my intentions were good, but the flesh is weak, and I let my friend George down. I was supposed to charge two shillings a cup, but after sampling a few myself it didn't seem too important, so everytime anyone came to me and bought one he was given one free. By the end of the evening I was the best customer, loaded but very happy, the "till" had very little money in it, and the barrel was empty. George never said one word of reproach; he was happy too.

The few weeks we spent in Cheshire weren't bad, and a few times we went to a nearby city for social functions given by the USO. This would be in the evening in the blackout area, so there were no lights on the streets or in the buildings. It was here we could see how the war was taking its toll on the morale of the young people. Everywhere we went a girl would approach us; even little kids on the street would beg us for a stick of gum and then ask if we would like to "play" with his sister. One night I was on guard duty across the street from a small park, and it was like an X-rated movie. They left nothing to the imagination, having intercourse right on the street, or on the fieldstone wall of the park.

A rumor circulated that we were going into the real thing very shortly, and surprisingly enough it was true. So many rumors went around that we had learned to discount practically everything we heard.

One day in the latter part of November we were told to be ready to move out on short notice. Within a week we were on the move to Liverpool where we boarded a troop ship to cross the English Channel. It was small and we were dammed together below deck because of security reasons. Conditions were filthy and it was a very rough crossing. The sea was so rough that it flooded the latrines, which backed up sending all that filth down the stairs to our quarters. There was nothing we could do to remedy this health hazard except to stay out of it as much as possible, and again be thankful for all those preventive shots we had been given. Breakfast was the first meal served to us and was more than we could take. It consisted of boiled beans and fat pork, served in mess gears that were thick with rust and grease and had apparently not been washed since God knows when. The Colonel took one look at them and ordered us to eat only the C rations we had been issued before leaving Cheshire. In doing this he prevented serious illness among us.

After fifteen interminable hours in that horrible hole we reached our destination, Le Havre, France. We anchored about one mile off the beach at the same location where the first wave of invasion forces had gone ashore the previous June. My buddy, Ray, and I were together all through the maneuvers in Fort Jackson and the Tennessee mountains and had managed to stay together on the trip across the Channel.. As we made our way up the stairs from that stinking hole we were the first G.I.'s to come on deck, and were shocked at the scene that confronted us. We saw bombed-out ruins of what had been luxury hotels and scores of other completely demolished buildings and tanks. It was at this point that we really appreciated the necessity of our long and tedious training in the U.S.A.

It was a miserably cold and rainy day

and the scene was one of dreary and ominous foreboding. Ray and I

sat on our packs and after looking at the ruins he said to me,

"Bill, I've seen enough of this war. Let's go home." All of a sudden

we heard a loud laugh and a voice said, "I'm with you!" It was the

Colonel, who was a very fine man and had a good sense of humor. One of the few things we had never been trained for was to climb down rope ladders from the upper deck of a troop ship to a landing craft that was to take us to the beach. But we had to do it even if we died in the attempt. The sea was very rough and the landing craft had difficulty getting close enough to the ship without hitting it and thereby having a bad accident. While awaiting our turn to go over the side, we watched the others do it and thereby try to learn by their mistakes what not to do in order to avoid getting hurt. When my turn came I didn't even know how to get on the rope ladder with my rifle and pack on my back, but I finally managed to do it trying to remember the instructions "Hold on for dear life!" As I got halfway down the ladder the landing craft was pushed away from the ship by the tide and I had to wait until It calmed down before I could proceed. When I reached the bottom of the ladder, I was horrified to see that the landing craft, due to the sea swells, was about two stories below me. I had to wait until they brought the craft up to about ten feet from me, threw my rifle and pack down first, then Jumped the ten feet.

It was hard for me to believe that I actually made it, and I said a prayer of thanks, because any one of us could have been crushed between the landing craft and the ship. The landing craft could not go all the way up to the beach, so we had to jump out and wade in icy water over our knees. When we staggered onto the beach we were wet, frozen, and disgusted. There was a big rock there and Ray and I sat on it and did some fancy swearing.

On December 6, 1944, the convoy of trucks that were to take us to our first bivouac area arrived, and we were transported in these open trucks over bumpy roads in the rain. But again, in spite of being cold and wet for days none of us suffered any bad effects due to our previous training and shots. We headed toward St. Vith, Belgium, through bombed-out towns which showed the real ravages of war. The people would come out and wave, giving us the "V" for victory sign, and it gave us a lift knowing that we were part of the rescue team. On December 10th we arrived at St. Vith and went to the front line the next day.

We relieved the Veteran 2nd Division in the Schnee Eifel, a wooded, snow-covered ridge just northeast of Luxembourg. This was supposed to be a quiet sector along the Belgium-German frontier, and it had been for the last ten weeks but was destined to change very soon. We were assigned to this sector in order to get experience. Little did we realize that we were going to get more experience than we bargained for in a very short time.

The 106th Division was strung out on a twenty-seven mile front, which would have been a great task for a well-trained division, but a much more difficult one for men who had never had any actual battle experience. In addition to this we were very young and very old men according to the standards of the average age. But in spite of our handicaps we held our ground, which was to be regarded as one of the most unusual feats in the Battle of the Bulge.

The late Field Marshal Sir Bernard L. Montgomery paid the 106th Division a very fine compliment when he said, "The American soldiers of the 106th Division stuck it out and put up a fine performance. By Jove, they stuck it out those chaps?"

My company, known as the Service Company RSO, relieved the service company of the 2nd Division of another regiment. It was billeted on a large farm about ten miles from St. Vith, which was the supply depot. Upon our arrival we inspected the layout of the house, barn, surrounding territory and guard posts which were dug into the ground. They were more like bunkers. We also discovered that there were hundreds of live shells piled up near the house we were to live in, so we had to be very careful of our smoking habits as we were literally living on top of a volcano. It had been an ammunition dump for the 2nd Division and remained the same for us. We lived and slept over the barn which had been the living quarters for the last German outfit to stay here. We found helmets, bayonets, and all types of equipment belonging to the Germans. The officers and first sergeant lived in another house fairly close to us. We turned the barn into the supply warehouse for food and other rations. When we drew our rations we piled them in the barn and broke them down into the various stalls marked for each company of the regiment.

Our first trip to St. Vith on December 11th was difficult because we did not know our way, but it didn't take us long to find a good route and soon we could travel by day or night.

I don't think we realized how near we were to the front lines until one morning when I came out of our house and found my buddy, George, guarding a truck in front of the barn. I went over to him and asked him why he was guarding the truck. "Well, Bill," he said, "I don't know why either, because the men inside couldn't go any place if they wanted to. They're all dead." The impact of this remark had a terrible effect on all of us, and I think for the first time we realized what we were to face. The poor kids in the truck were our first casualties, and had only been on the lines a couple of days when they were slaughtered. Such is the folly and tragedy of war!

Every guard post was equipped with a cot and a fifty caliber machine gun, and of course we each carried our own rifle. I asked the first sergeant to show me how to operate the machine gun, as I had never fired one and had no idea how it worked. He gave me fast, sketchy instructions, and it was lucky I never had to use it because I don't think I could have managed it.

On the night of December 16th I was to get my first real baptism of the front lines. My partner and I were on guard duty, which was from midnight until six a.m. Our post overlooked open fields and we could see for miles. The post was not to be left unguarded for a minute, so we would take turns resting on the cot while the other stood guard. It was while my partner was taking a rest and I was standing guard, manning the machine gun and on the alert for anything unusual, that I heard a noise which sounded like a firecracker being thrown into an ashcan. This didn't alarm me too much as we were used to hearing cannon and small-arms fire in the distance. But this time there was a screaming, siren-like sound very close to me accompanied by an explosion, and each time it occurred it seemed to be getting nearer. After standing at the front lookout window for a few minutes I noticed a flash and heard the same sound even closer. We learned later that these were called "nebelioerfer", or as we called them "Screaming Miemies." I awakened my partner and we decided that the captain should be advised of what was happening. So I crawled down to the captain's house on my belly and after pounding on the door for several minutes I was able to awaken the first sergeant who informed me that the captain was not there but would return In the morning. I persuaded him to come up to the post with me and see what he thought of these happenings, but he did not venture an opinion nor issue any order except to ask me to accompany him down the hill to the house. I thought this was a pretty small thing for him to do, as he was in command at the time, and knew I would have to go back up the hill alone. In any event, the night passed without anything drastic happening.

The next morning, December 17th, we went with four trucks to St. Vith for our rations. It was about nine a.m. and we did not notice anything unusual, so we proceeded to load the trucks. The supply sergeant had the first truck leading the convoy, I was in the second truck, being second in command of the ration detail, and the other two trucks followed us. While we were loading our supplies suddenly, to our horror, the schoolyard and entire town was suddenly under bombardment, and we found ourselves in the midst of what was later known as the Battle of the Bulge! We took off like a shot with what supplies we had and started out of the schoolyard, but didn't get very far when an M.P. stopped us. He said the Germans had broken through and if we kept going in that direction we'd run right into their lines. So we changed our route which took us through a small town called Orr, but after going two or three miles we ran into a lot of small arms fire and the further we went were almost hit by artillery fire. In fact, one of the shells burst so near to my truck that it blew the door in on my leg. Fortunately the doors were not made of steel, just canvas and plastic, so I was not injured.

The first truck stopped and the sergeant came back to me and said we had better take cover in the nearest farmhouse,, which was about three hundred feet back. By this time there were only two trucks left; the other two must have turned back and I never did find out what happened to them. Our only way of getting to the house was by crawling on our stomachs in snow which was knee-high. It was tough going but we finally made it.

The house was typical of those in the vicinity, made of beautiful gray fieldstone, with the barn under the living quarters, and beneath that a very large cellar.

We found a lot of men of the Engineer Corps who had also taken refuge there, and all established defense positions at windows of every room facing all directions. This we felt would give us a chance to make a stand against an infantry assault. Across the road there was a very large wooden building resembling a barn. The window of the room facing the road to the east had a machine gun which was being manned by a crew of young men of the Engineer Corps. Two of the men from my convoy and I were in the room facing the south road, and we could see a good distance away in spite of all the snow. We were told that the farmer and his family were in the cellar. The noise of the small arms fire decreased gradually, and if we had been smart we would have realized that it was too quiet to be good.

Suddenly I spotted a jeep coming up the road. It stopped outside of the house and a U.S. Army captain and his chauffeur entered and took command of the situation. This was understandable as he was the ranking officer. After inspecting the downstairs defense positions he came in to give us Instructions. First, he told us there were a lot of the enemy in the big barn across the road and we were to flush them out. He instructed the young lads in the room facing the barn to fire the machine gun, but to use tracer bullets which would set fire to the barn.

The order was carried out and the barn was in flames in minutes, but not a soul came out of it. In a short time I saw an object coaling up the road in a cloud of dust, but could not define what it was. As it came closer I recognized it as a tank but still could not identify it as a U.S. or German one. I went downstairs to tell the captain, who looked at It and said, "Boys, this is it !, The armored cavalry is coming to our rescue." Then he went downstairs, but as they came closer I could see them more clearly and as soon as I saw the white capes on the men in the first tank I knew immediately that they were German Panzers. So down I went again to the captain and told him they were German tanks. He came up, looked at them, and said, "You're right, they are German." He turned around and went Into the room where the young lads with the machine gun were stationed and told them to open fire on the tanks when they came close enough. As soon as he went downstairs he must have left the house immediately, as we never saw him again. We realized later, but too late, that he was obviously a German in disguise who set us up by having the barn set afire in order to signal the Panzers as to where our line of resistance was.

As the tanks approached the house the boys in my room threw themselves flat on the floor and started to pray. The lads in the other room, following the "captain's" instructions, opened fire on the tank, which was the worst thing they could have done. The first tank stopped, trained its 88 mm. cannon on the machine gun nest and fired, killing everyone above and below with the exception of a few, including myself, who were miraculously spared, and continued down the road. We found ourselves out in the open as the entire building had been demolished except for the staircase leading to the cellar. We ran down and found the farmer with his wife and family, and a few engineers who had also been lucky. My supply sergeant must have taken off as soon as we went into the farmhouse, because I never saw him In the house and he was not among those in the cellar. Apparently he did not care about the rest of us because he failed to take the trouble to at least call up to us that he was going to make a run for it. I do know for a fact that he survived the war.

While we were in the cellar trying to decide whether to surrender or make a stand, the farmer's wife became hysterical and started to scream and cry. The sergeant from the Engineers, who took charge of the situation, told the farmer to make her stop or he would have to shoot her. This had the desired effect and when her husband spoke to her in German she looked frightened and quieted down. Then another thing happened while we were still studying our chances of survival when the Germans came for us. A real young fellow from the Engineers broke down, probably from battle fatigue. He was shaking all over and begged me to sit on him. He kept yelling louder and louder so I thought it best to do as he asked, and after sitting on him for awhile he became very quiet, stopped shaking, and in about ten minutes was fairly normal.

An hour had passed since the tank hit us and we were still undecided whether to fight or surrender when the clean-up patrol came for us. The sergeant in charge called a conference and said, "Fellows, I am going to let you make the decision whether to fight or surrender. There is only one way we can make a stand and that is to wait for them to come down the stairs and fire at them. This will undoubtedly be suicide for everyone. I will go along with you if you want it that way, but would like to tell you how I feel about it. I have a family back in the States and I sure would like to see them again, but I am only one, so you will have to take a majority vote and decide." It did not take us long to make a unanimous decision to give ourselves up. The sergeant then instructed us to dismantle our firearms and throw the pieces where the Germans could not find them. This was accomplished within minutes.

About an hour later we heard the rumble of tanks close by, then footsteps above us and the rattle of the metal chains of their automatic weapons. The sergeant told the farmer to send his wife out to the German soldiers and tell them that we would surrender, which she did, and in a few minutes we saw them coming down the stairs with their guns pointed at us. The one in charge called to us to come up with our hands over our* heads, and we could understand him as he spoke excellent English. We were fortunate, too, that our sergeant was able to converse in German.

When we went outside we saw what were called Tiger tanks, each of which was mounted with an 88 mm cannon. There was barbed wire fencing around the entire property, and we had to climb over it with our hands over our heads In knee-deep snow.

This was very difficult, but it's amazing what you can do when you have no choice, so we all made the fence. Then we had to stand between the two tanks for a long time in the freezing snow and cold with our hands over our heads while they searched us for hidden weapons. Upon completing their search they ordered us to march between the two tanks with our hands still over our heads. Unfortunately for me, the soldier who had opened my belt neglected to close it again, so as we walked my pants began to slide down. I was in a state of panic and kept yelling to our sergeant for help but the roar of the tanks was deafening and it took what seemed an eternity before he heard me. He quickly called to the tank commander and told him about it just in time, because in a few more seconds I would have fallen and the tank would have gone right over me. The tanks were immediately halted and the commander came down to me, pulled up my pants and closed my belt. He seemed to think it was very funny and laughed very hard. Then he motioned to the tanks to go on.

Soon after my near-fatal incident we arrived at the command post which was in a small town about three miles back from the farm, and opposite an old church and graveyard. We were marched Into the command post for questioning by a lieutenant of the intelligence corps, and lined up along the side of the room. The officer was sitting on an old desk and he called us one at a time, asking our name, rank and serial number. That was all he could get out of us in spite of all the questions he asked without success. However, he did not have time to pursue it because the town was suddenly bombarded by our forces. Although this saved us from further questioning we were still standing against the wall and praying that we wouldn't be killed by our own shells. At this time we were still the prisoners of the "elite" Panzer Division, identifiable by their white capes and automatic weapons attached by long chains around their waists. They were beginning to take a lot of punishment and losing many men, and we were getting more nervous every minute. We could not move, but could see what was happening outside. Suddenly a shell came through the back of the building and we all fell on our faces to the floor. When the dust and plaster cleared away we looked up and were surprised to see the officer still sitting on the desk. As we arose and resumed our position against the wall he looked at us calmly and said, "You see, if you had been killed that time it would have been your own shells that did it."

There was an American medic with us who was watching the way the Germans were getting knocked off, so he went up to the officer and asked him if he would like him to help pull some of the wounded and dead Germans off the street. The officer was so surprised that at first he didn't seem to know what to say, but in a few minutes issued an order to his own men to carry the wounded and dead into the building. It was a terrible sight, seeing them pile up the dead men like rolls of dry goods. It was so cold they froze very fast after they were killed.

There was a big fellow standing guard on us in the doorway of the room, and everytime they brought in a dead German he would look at us, and it made us feel very uneasy. Finally he said to us, "You see, war is nobody's friend. First it is us and then it is you." This remark did not help our morale as we had to remain silent although we wanted desperately to say, "Well, it was you Germans who started it!" After about three hours our sergeant went up to the officer and asked him when we were to be moved out of the combat area, quoting the rules of the Geneva Convention as he understood it. The German looked at him and said, "I see you know the rules of the Geneva Convention and I assure you that when I have the proper men I will see that you and your men are moved out of the combat area." It was not long after that we were moved from there, but just as we emerged from the building the church and graveyard were hit by a barrage of shellfire, and coffins and corpses were flying all over. This was another terrible sight I will never forget.

Although we were relieved to get away from the town we were dreading the thought of what lay ahead of us, because of the stories we had heard of the rough treatment we were probably in for. But luckily for us we were treated as soldiers and honorable prisoners of war. After marching through many towns we were very tired and hungry, not having eaten in two days except for candy bars which we had in our pockets and shared with each other. This kept us from starving for the time being, at least.

(At this time I would like to point out the fact that I was very lucky to have been captured by the Panzers and eventually turned over to the Wermacht Division, as these were soldiers who were conscripted and operated according to the rules of warfare. If, on the other hand, I had fallen into the hands of the S.S. troops it would have been a different story and I would not be here to tell it.)

There was an intelligence detail assigned to question us at almost every town we marched through, and as we arrived we'd be lined up, questioned, and then added to a long line of prisoners who had already been interrogated. It was at one of these places that I did something that could have cost me my life, but at this stage of the game I figured the odds were against me anyway. There were about fifteen men in front of me waiting to be questioned, and I waited for the officer to turn around for something, at which time I moved over to the line that was ready to go out. I often wonder what would have happened to me if they had caught me.

We marched well into the night until we reached a large field where the moonlight disclosed a German armored outfit that was bivouaced. We were turned over to the commander who split us up into groups and told us to sit beside the tanks and rest, even smoke a cigarette if we had one. The Germans who were guarding us stood there looking at us longingly while we were smoking, so we offered them a couple of puffs and they thanked us. By this time even cigarettes were very scarce among the Germans.

At dawn we were on the move again, but had to be escorted by special soldiers because the fields we were going through were mined and these men knew just where it was safe to walk. We followed them as we thought away from the combat area, but actually were getting closer to the action. The Allies had regrouped and were beginning to hit the Germans hard, pushing them back into Germany. It was getting real rough for everyone.

One night we were taken to a farm near a town which had been captured by the Germans. They crammed six of us into a woodshed about the size of a utility closet and secured it with a padlock. We were given four bars of chocolate to divide between us. They were American C rations which had been picked up by the Germans when they took the position. By now the action had begun and the entire section was hit by an artillery barrage. The shed we were in was wooden and ready to fall apart, so we could see everything outside through the cracks. Some of the dirt from the explosions came right through the cracks on top of us, but luckily our shed was not hit although the entire town was soon blazing.

In the morning they released us from the shed and marched us back through the still blazing town. All we could see were dead Germans lying around the farms and fields, side by side with animals who had met the same fate. It was a horrible sight. We came to a hilly section to await another column of prisoners. All the German equipment and artillery were horse-drawn up the hills of this mountainous country. This was probably due to the now severe fuel shortage which was one of the factors responsible for the Germans' growing problems. Even they were hungry, shooting whatever game they could from the ground.

One night we were moved to the side of the road to allow a German artillery regiment to pass. One of the officers came up to us with his aide and began taking our gloves and anything we wore that was warm. They took my helmet liner and stocking hat, which left me without anything to keep me warm. After they passed we started marching again. We had to travel by night as the situation was getting very dangerous and they couldn't chance being seen from the air, We finally arrived at a farmers' dorf and were taken to a very young officer of the German outfit which had occupied the town. We were lined up so he could inspect and question us, and we were surprised to hear his flawless English.

He went down the line and asked each prisoner a few questions, but all he got out of anyone was name, rank and serial number, and he would just smile at the answers. When he came to me he said, "How old are you?" and I told him thirty-eight. He asked me where my helmet liner and gloves were and I told him that at our last stop a German officer had taken them for his own men. He looked down the line and saw a young fellow who had managed to keep his gear; so he told him to give me his helmet liner. It sure was a great help to me. Then he looked at me and said, "I love Times Square in New York," and passed on. I doubt if he'd love it if he saw it today.

We had lost all track of dates and time, but by now it must have been a week or so since we were captured. As we continued our march it was further back of the lines, so we proceeded from the air by the Allies and the Germans were running in all directions to get out of the line of fire, some carrying their wounded, others badly hurt, and some never made it. They were hit very hard by the strafing and small bombs intended to destroy their armored column and supply sections. It was a large town and the school we were brought into was tremendous. We were very hungry, not having eaten in two days or more, and asked the sergeant in charge of the prisoners for food. He said it would be hard to get because of what had Just happened but he would try.

The townspeople were incensed by the raid and the enormous amount of damage incurred, and showed great hostility toward us, but the sergeant managed to scrape up some military bread and water which was not much but helped a little. The people were beginning to get nasty, and insisted that we be moved out because they were afraid the planes would return due to our presence. The sergeant, being responsible for our safety, moved us out and after marching all day we stopped at another large town for a night's rest. We were locked in a factory that had been used for tanning raw hide and leather, and had a peculiar odor. To tell the truth, any place off the streets and under a roof looked good to us. Everywhere we went the Germans were being hit hard by the air raids, and the war was turning against them, taking a large toll, so it wasn't surprising that within minutes the air raid alarms began wailing and we heard planes going overhead. They must have been going after something bigger than us, but not too far away, because we could hear the bombs bursting and see the flames. The next morning we passed through the town that had been hit and It was still on fire. It had been a supply depot for uniforms, firearms, and medical supplies. One village in particular I will never forget. As we marched through it the people were very antagonistic towards us and hollered mostly in German, but we could understand enough to know that we were being called swine and pigs. Suddenly a potato was thrown out of a window and hit me squarely on the nose. I can feel it to this day, and know my nose was broken. The funny thing is that what bothered me even more than the pain was the fact that someone behind me swooped up the potato and ate it. I felt that I should at least have had the privilege of eating it.

Surprisingly enough, at the next village we came to and stopped for a couple of hours the people were entirely different. Perhaps it was because it was a small place and they had not felt the effects of the war too much. They came down to where we were herded like a bunch of cattle behind a wire fence and we leaned against it with our hands pressed outstretched, begging for food. They were very kind and the women brought us bread, jam, and cheese hidden under their aprons and slipped it through the fence to us. Actually, the German guards were glad we were being fed because they had no way of getting food to us, so I'm sure they wouldn't have objected. There seemed to be an even kindlier feeling toward older men, because I heard one woman say to another, "Nix kinder, give it to the older kocker," meaning me.

We hoped that when we left the city

area and headed for the farmlands we'd be out of danger, but were

mistaken. We stopped at a large farm and stole some sugar beets and

potatoes which weren't very appetizing as we ate them raw, but at

least they kept us from starving. Suddenly we heard small arms fire

and saw to the west of us that a column of supply trucks was being

attacked from the air. The earth shook under us and it felt like the

next thing to an earthquake. Bombing was also going on in a

township to the south of us. We were tense, realizing that we were

in the middle of a situation that could very well engulf us. We

gathered what little supplies we had left and started marching again

that night. We moved in the direction of the bombing and when we

passed the target every building was burning. It was an awesome

sight. As we went along more prisoners of war were added to our line, many of them Canadians, Englishmen, and Australians. It was not until the war had ended and I was home that I discovered the brother of a very close friend of mine was in the same line of march with me. He was a major in the Canadian army. We crossed a little bridge over a small river (I was at the end of the column) and when we were about five hundred yards away from the bridge the Germans blew it up. This gave us a great lift, because it was an indication that the war was not going in the Germans' favor. Later we learned that the previous days bombings had wiped out a secret ammunitions depot that the Allies had been unable to find until now. It had been difficult to pinpoint because it was built entirely underground and the surrounding territory was so hilly it was impossible to detect from the air. No doubt a reconnaissance plane finally spotted it.

When we entered the railroad station

of a small town en route to a prisoner of war camp the townspeople

were busy preparing for Christmas, so it must have been December

22nd. German soldiers and civilians gathered around and stared at

us, and one soldier in particular we noticed did not like us at all,

as we could see him making gestures with his hands like a machine

gun. He no doubt was telling everyone that we would mow us down if

he was in charge of us. One night the train halted and we could see through the cracks that the sky was bright and clear. The Germans jumped off the train and took cover alongside of the tracks, which were hidden by the heavy forest. We knew it was Christmas Eve as they were playing "Holy Night" on a harmonica. Their celebration was short-lived because an air patrol spotted us and dropped a few small bombs which fell short because of the thick cover of trees. The air patrol may have suspected that we were a prisoner of war train because they did not continue the attack.

Meanwhile the conditions inside the car were getting worse every minute; more dysentery and nausea, and no food for days. The next morning, which I believe was Christmas Day, we arrived at a station on which the name was covered as they did not want us to know where we were. They opened the doors of the cars and we straggled out very weak, but after the foul air we had been inhaling the fresh cold air was like a tonic to us. We were made to stand in formation on the platform for some time, and as bad as the hunger and cold were, nothing could compare with our thirst. One of the lads was allowed to go into the station and fill his helmet with water, and we took turns drinking from it. I begged him to let me wet my lips and because of my big mustache which absorbed a lot more water than I could drink at one time, my parched lips and throat were well quenched.

The train was composed of almost twenty cars, and we saw a lad being carried out unconscious. We heard later that he had died of diphtheria. While the cold weather was very hard on us it prevented serious epidemics of all kinds of diseases.

They marched us up a steep hill that was more like a mountain to a prison camp, and after all we went 'through to get there the camp commander refused to take us because they had been bombed the night before and some prisoners were lost. The dysentery was getting to more of us all the time and I can tell you we were a very sick bunch of men. If you were not ill yourself you felt sick looking at the poor devils that were. There was no way of cleaning ourselves, so down the mountain we went again to be put in the same filthy box cars, this time even sicker and dirtier. The next day we thought we would be taken into another prison camp but it was for officers only, so on we went again.

The following day we arrived at Hammelburg, and were again marched a good distance to a prison camp. This was called Stalag XIII-C. Here we were accepted and sent to barracks. We were called down to the mess hall and told to bring our canteen cups with us. They fed us bread and sauerkraut soup, which nearly killed me. I couldn't sleep with the excruciating pain and nausea. I made my way through the snow to the latrine where I fell over with the-pain. No one was there to help me so I crawled to the nearest barracks and hollered for help, and finally a guard came along and half carried me to the next barracks where a Russian doctor and an American medic, both prisoners, were running a little sick bay for the prisoners. I thank God for these wonderful men because they saved my life.

They sat up all the rest of the night with me and forced me to swallow some medicine that emptied my stomach and did the trick. They told me I had to stay in bed for a day because I was too weak to walk or move about, and I was left alone for a whole day to pull what was left of myself together. My only way of thanking the doctor and the medic was to give them the few cigarettes I had saved from my last issue of C rations, and they were very pleased.

The next day the new prisoners, including myself, were taken over to what we were informed was the processing building. After being brought into a large room, we were told to strip naked and put all our clothes Into a furnace. Then we were instructed to walk into ano.1ier room, on the same floor, which looked like a big meat freezer in a market. The room had no windows and just one small door with a little window in it, sort of like a peephole. At this point I was beginning to recall all the stories I had heard about the gas chambers at Dachau where all the political prisoners had been put to death by gas. As we were ushered in we could see the overhead pipes and this made us all the more positive that it was the end of the line. We stood in the room waiting for God only knew what, when the door opened and an officer walked in and looked us over. When he came to me and saw the "apron" of skin hanging down over my front, he said with a smile, "Grosse belly!” slapped me on the back and walked out laughing. Then, to our horror, we saw a mist of vapor coming out of the pipes and all prepared ourselves for death. But to our surprise it was heavenly hot water, and then we noticed homemade soap on a high shelf. This gave us a new lease on life and we reveled in cleanliness such as we had not known in a long time. It was certainly a much different fate than we had envisioned. The clothes issued to us were not bad and at least were clean, a new experience for us in a long time.

There were some Australian prisoners, who had been in the camp for some time, and they were in charge of such things as having us recorded with the Red Cross and making sure we were all accounted for according to our dog tags. They were great men and did all they could to help us. They even warned us about what we should and should not do, such as sleeping with a German woman. They told us that if we were caught doing it we would be shot, and deservedly so.

We were all given different jobs, such as piling up military supplies in the warehouse and clearing the snow from the highway near the prison. Besides being a prison camp it was also a training camp for German army recruits.

An English chaplain named Captain King, who was also a prisoner, visited our barracks every couple of days. We would discuss things that were going on around us, and every time he left us as he was going out the door he would say, "Remember this one thing that I say to you; the Spring will never come. Amen." I'm sure he was trying to tell us in a subtle way that the war would be over before the Spring of 1945.

After a couple of weeks in Stalag 13C we were split up and sent to different parts of Germany. I was sent to a stone quarry not too far from the prison. We left by train in the morning and arrived at night in a little railroad station deep in the mountains. There were about ten of us, and in order to prevent our planning an escape they arranged it so that none of us knew each other.

Two soldiers came sliding down the mountain on snowshoes to take us up to the quarry. This was a very hard trip for me because of my age and condition, and I could not travel upgrade very fast in the snow. One of the guards led the group and the other stayed in the rear. We formed a single line and I was the last one on it. We had to follow the guard's footsteps in the snow or we would sink into it up to our waists. It was lucky for me that they were "good Joes" because I fell many times and the guard in back of me would pick me up and try to make it easy for me to follow the rest of the men. By the time we reached the top of the mountain I was on the verge of collapse, but they put us immediately into a house that was like a palace compared to what we had been in before. Each room was equipped with four bunks and a belly stove. It was very comfortable, but we had to be careful using the coal as we were allotted only one pail a day.

The next day we were sent to work at the stone quarry which was a good distance away, and we had to travel through snowy mountain trails by foot. Our job consisted of using a big sledge hammer to break the big stones into small ones and put them into mine cars that were on tracks along the side of the mountain. Then we pushed them to what we called a grinder after which they were sent to a cobblestone manufacturing plant. We worked an eight hour day, being given a hot lunch which was brought up from the mess hall. Our evening meal was equally good, and we ate in a very clean mess hall. We took turns at cleaning, just like K. P. duty.

One day as we were working at the quarry the air siren went off. We had been told that some day we would see an unbelievable sight, and it really was one I shall never forget. Hundreds upon hundreds of Allied planes returning from a mission flew over our heads in close formation and actually blotted out the sun. It seemed almost like night had fallen suddenly, and you couldn't see the end of them. I never saw so many planes at one time in my life, and they sure looked good to me because they were ours.

Once again, something happened to me where I nearly met my Maker. One of our jobs was to ride a carload of stones downgrade to the grinder, and we had to use a tree that had been trimmed down as a brake. This particular Saturday morning I was on my way down with the stones, but the tree must have broken because I found I was gaining speed and couldn't slow the car down. It kept going faster and faster and was approaching a sharp turn, so knowing I couldn't stop it I jumped off just before the car went over the side of the mountain. Again, God was with me. Sunday, which was usually our day of rest, was spent by some of us pulling the car back up the side of the mountain.

Two of the guards, Hans and Eric, took a shine to me possibly because I seemed old in comparison to the kids in the work crew. I was made a combination overseer, mediator, or sort of a go-between, so that when anyone had a gripe he would come to me, I in turn would talk it over with the guards, and we'd eventually straighten it out. Most of the guards could speak English, but not too well.

One day the mayor of the town below the quarry asked for two men to work on his grounds and generally clean up the place. Another prisoner and I were chosen, and the day's events produced a series of surprises. When we arrived the housekeeper took us down to the cellar which was furnished like a game room. It had a small kitchen where she served us hot coffee and homemade bread and jelly. Then we were put to work. In order to irrigate the field and garden we had to pump out all the liquid in every outhouse throughout the entire town into a tank and then pull it all the way to the fields. It was quite a distance to haul the tank without the aid of a horse, but we managed it and were finished by noon. Then we received a pleasant surprise. A man called to us in English while we were in the garden and told us to clean up and come in to eat. We certainly never expected war prisoners to be treated as we were. We were escorted upstairs to one of the most beautifully furnished homes I have ever seen. The living room was elegant, complete with a grand piano, and everything was in excellent taste. The sun porch was also lovely and a table was set for four with white linen cloth and napkins, and beautiful china and silverware.

The mayor and his wife entered the room and greeted us very warmly. They both spoke English very well, with just a slight accent. The mayor's wife told us she had arranged a menu that would make us feel a little like home, "I made you boys a Mulligan stew that I tasted when I was in Florida," she said. She told us how much she liked America and hoped to go back for a visit some day when the war and all the trouble was over. The mayor talked about politics and the war in general, and we could gather from his remarks that he did not like the whole thing. He walked with quite a bad limp which he may have had as a result of the war. After lunch we smoked a cigarette in the living room and the mayor's wife discussed cowboy music which she said she loved. We told her there was a prisoner in our camp who played a guitar and sang country music, and she said if she could get permission from the authorities she would like us to bring him over some evening. We never were able to do this because shortly after that day we were moved out.

Going back to the quarry was a depressing change for us. The work was very hard and we were so exhausted at night we had no trouble going to sleep. One morning I awakened feeling very sick to my stomach and called Hans, who told me to go back to bed. He gave me some tea he brewed from wild herbs and peppermint leaves, and in a few hours I was up and feeling much better.

Believe it or not, we were actually paid for working in the quarry. The truth of the matter was that they wanted it shown on their records that we did not work for nothing so they would not have to pay us again when the war was over.

Actually, the German marks we were given were practically worthless, but we spent our "salary" on Saturday nights in the mess hall for a couple of bottles of beer that was brewed on the premises.

One Saturday an old man who lived nearby came into our room and sat on one of the bunks. He began to talk in English about the United States, and said he had owned a delicatessen store at 34th Street and 10th Avenue in New York City. It seems that while he was over in Germany on a visit the war was declared and they would not let him return to the States. We had to be careful of everything we said to these people, as many were in the Intelligence trying to get information from us. But I was inclined to believe this man because he was old and did not ask us any questions about ourselves, but seemed more interested in the neighborhood where his store had been. Before he left he gave us a big rabbit he had snared, and we cooked it up as a stew on top of our stove, and it was very good.

One day our regular guard was replaced by a strange one, and a couple of Australian prisoners came, or I should say, tried, to visit us. The Aussies, as they were called, were quartered with families in the town nearby, and having been there for a long time were pretty free to come and go as they pleased. But they ran into trouble with this strange guard who was very unfriendly. When they knocked on the door he opened it and after a few words he started to beat them over the head with his rifle butt. They called him all the names you could think of and we heard one of them say, "You German bastard, I hope I'm near you when I'm liberated so I can have the pleasure of killing you slowly !" The next day our regular guard returned, and we assumed that he had been called away to be given orders because we were moved early the next morning after breakfast. We left from the same station where we had arrived about three weeks previously, and were given a bag of food to eat on the train as we would be traveling most of the day.

We traveled in circles, probably for security reasons, so we rode about sixty miles, and very slowly at that, in order to cover thirty miles. Finally we stopped at a town about five miles outside of Bastheim, a farmers' dorf, and they walked us the rest of the way to Bastheim. The Allied Air Force must have been here before us because there were quite a few craters on both sides of the road and also a few big bombs that were duds. It was a cold clear day In February or March, probably the latter, because the fields were starting to come alive with crops.

Upon arriving at the dorf late in the afternoon we were marched into what had once been a guest house and a gas. station before the war, belonging to a Jewish family. But they had either fled or had been taken prisoners, and now it was government property used to house the slave labor which were the prisoners of war. As we were lined up I could see there were only about three of us from the old gang at the quarry, and the rest of the men were all strangers to me. This was all carefully planned, as they never kept the same prisoners together for very long, to avoid their planning an escape.

The farmers were notified to come down and each of them was to select one of us to be his slave. They looked us over carefully, asked us questions in broken English, had us turn our hands up to see if we had good strong palms, and if by any chance you had callous on your hands the farmer would be very happy and take you immediately, knowing you could do a good day's work.

All the younger fellows were picked first and after what had been a crowded yard it started getting pretty empty. It got to the point where there were only two of us left standing there, and pretty soon I was the only one left. I felt like a leper, but the truth of it was that I looked like hell. I was a sorry-looking sight, with a bushy red mustache that made me look like a walrus, my hair which by now was snow white and down to my shoulders, and my clothes which were tattered covering a huge frame with very little flesh on it.

All in all, it was obvious that I hadn't made a good impression. A woman, who was a late comer, entered the yard and as I was the only one left she had to take me. She looked me over, and when she saw my hands she shrugged her shoulders and said, "Comesa here." So I followed her to the farmhouse and as soon as we arrived she sat me down at the table and gave me a good hot plate of soup and lots of homemade bread. This was my first experience in Bastheim and while I stayed there I had no complaints. The family consisted of the woman, Elsie, her parents, (Momma and Poppa), and her small son, Helmar. They were good people and treated me well while I was there.

Every morning the prisoners would be up at 5 a.m. and leave our housing quarters, walk to the farm assigned to us, and return at five or six in the evening. Each farmer was responsible for providing us with our bed and bedding. My bunk was not so bad. My master, as he was called, lived about a quarter of a mile down the road, which was a short walk. Upon my arrival my first task was to clean the cow barn and currycomb the cows. The farmers were very strict about this and took pride in the appearance of their animals. It was still very cold outside so when I finished this chore I waited in the barn which was connected to the kitchen by a door. At about seven o'clock Elsie would call me in for breakfast which consisted of coffee, bread and jelly, which was not bad.

One day while I was working in the

barn Elsie came inand when she looked at my pants which were all

ripped up the leg she left the barn and returned with a pair of

Poppa's which she told me to put on while she repaired mine. Of

course they were so small I couldn't even get a leg Into them, so I

sat in what was left of my underwear until she returned with my

pants a little later. She did a damn good job on them. Now that the weather was improving a forest detail was formed. On different days a farmer and his slave would go up into the mountains to out down trees for his own use. We would leave the house in the morning after breakfast and stay away most of the day cutting and collecting trees. We brought a lunch of boiled eggs, bread and beer. We were not allowed to drink the water because of the mineral content in it. After chopping the trees down we went home and returned the next day with a cow pulling an open wagon which we filled with logs and then headed for home. As there was no coal to be had a tremendous amount of wood was used each day for heating and cooking. The huge stove in the kitchen required a never-ending supply to keep it going. One of my jobs for several days was to chop the logs into kindling wood and carry armfuls up a ladder to the storage loft. Each piece of wood had to be uniform in size and stacked in neat piles. After I had finished doing this at the end of each day the farmer would inspect my work.

It didn't take me long to discover that I was not anymore popular with the livestock than I was with the Germans. Our barnyard population consisted of two cows, many chickens, geese, and one gander which was known as the "fuehrer" of the dorf. He didn't like me, and I don't think the cows did either. The first time I became aware of this was one morning when I went between the two cows to clean up the mess they had made overnight. This was a mistake, because when I got in the middle of them they pushed against each other and began to squeeze me until I could hardly breathe. Luckily I knew enough to use my elbows on their stomachs, and when I hit them they moved away, to my great relief. It happened only once, but that was enough.

I never was able to get the gander to like me. He was really my worst enemy and hissed at me every morning when I entered the yard. One morning as I was walking towards the barn he suddenly came out of nowhere and grabbed me by the seat of my pants. It took me a long time to get him off and I had a very sore backside for a long time. When I told Poppa what happened he made a long switch which I carried with me when.. ever I was near where he might be, so I could hit him over his neck. This was the most effective place to hurt him, and I was dying for an opportunity to do it. We were well into March and the weather was getting nicer, so we started to make trips to Poppa's farmlands which were two or three miles away from the dorf where they lived. It was amazing how they knew their boundary lines because they had neither fences nor markers, just stones piled in a certain way around their property. Elsie, Poppa and I always took a cow and wagon which we used to put all the twigs, stones, and other debris which we found on the ground, so we could plow and seed the fields. On the way to the fields the old man had me sit on the back of the wagon while he and Elsie walked. This was not exactly a charitable deed, merely a way of preserving my strength for harder tasks. Once at the fields we would hook the cow to the plow and I'd get at the other end and steer it.

It was here that for the first time Elsie and I had a run-in. She tried to tell me what I should say to the cow so it would pull the plow in the direction I wanted to go, and obey my commands. The trouble was that it could only understand German, I could not speak it, and I also couldn't understand Elsie’s German. Each time I hollered at the poor beast it would either stand still or go in the wrong direction. This made Elsie very angry at me and the poor cow who was the victim of my bad German. One day she called me a "dumbkoff" which meant stupid. I called her a stupid German bitch, which luckily she didn't understand, but it made me feel better. After a couple of days I learned how to shout orders to the cow in German, which sounded something like "hoopalar" and she would take off like a shot Before long I was accepted almost as a member of the family. When the old man was not present for meals I would have to say "Grace." The family was of the Catholic faith as were most of the people in the Bavarian Alps and surrounding territory. The prayer consisted of a decade of the Rosary which I said in English and they answered in German. The boy, Helmar, who was a nice kid of about ten, went to school every day. His father was in the German air force and was either dead or a prisoner of war, as they had not heard from him in a long time. After dinner, before returning to my barracks I would help Helmar with his bible history. I could not read German but the pictures in the book made it easy for me to convey to him the stories it told, which I managed to do by sign language and poor German. This pleased the family very much, and made me feel pretty good.

Momma was about eighty years old during the time I was! there, but she used to personally come into the yard or barn where I was working and bring me a piece of bread and jelly and a glass of the most delicious cider I have ever tasted. She always came out at about three o'clock in the afternoon, and would hide the food under her apron so no one passing by would see what she was doing.

During the end of March the entire dorf became very active In brewing a new batch of beer for Easter, and this was to last for the entire year. Every farmer would contribute something for the occasion: malt, wood, and their slaves to help cook it. There was a brew house in the middle of the town that was used only once a year for this purpose. We, the slaves, had different duties to perform. We had to keep stirring the whole tank of liquid and never let it settle. There would be two men at a time on a platform built around this enormous tank. After one hour of this chore we would be relieved by two more men and then after resting awhile we'd go on the fire detail. It was very important that the fire be kept at a certain degree of heat so that the brew would just simmer. We were searched before being allowed to go near the brew, as they told us that any kind of bread, pastry, or food near the tank would ruin the quality of the finished product. After three days and nights of cooking, the brew was left to stand for a day or so to settle. Then it was ready to be divided between the farmers.

We, the prisoners, had big metal

containers strapped to our backs which were filled up. We had to

walk back to the farmhouse very slowly with our arms folded across

our chests so as not to spill a drop of the precious brew. Upon

reaching the house Poppa would take me down to an earthen cellar,

which had big hogs' heads all around in a circular position. Each

hog's head had a fresh-cut pine bush on top and a platform of one

step which I had to climb up on and lean over sideways to pour the

contents through the pine bush in order to strain it. This trip was

repeated at least five times until the beer was evenly divided

between the farmers. The cellar was then closed and not re-opened